Source: Berlin Policy Journal

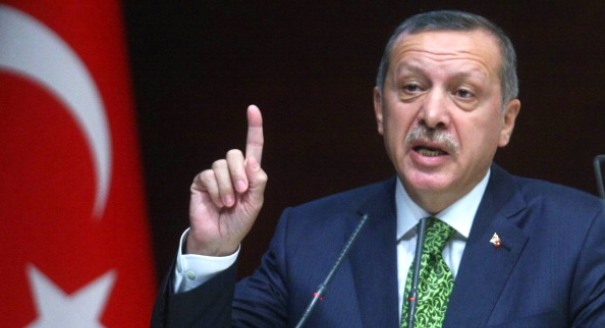

After the failed coup, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is more unpopular than ever in the West – but reconciled with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Are we witnessing a Turkish strategic pivot?

No, I do not read it as such; otherwise we wouldbe in a very different world. Despite everything that has happened, Turkey remains anchored in the West – in political, security, and economic terms. The establishment of a strategic partnership with Russia is somewhat far-fetched. Realistically, there is little that Moscow could offer Turkey to replace its relationship with the West, whether economically or viewed from a security perspective. So there really is a limit as to how strong, how potent this message of rapprochement with Russia can be. However, it is useful for Ankara to be able to demonstrate to the West that Turkey could potentially have other options – as at the recent St. Petersburg summit between Erdoğan and Putin. And it’s noteworthy for a different reason, too. Putin is the second head of state Erdoğan met with after the failed coup; the first one was the president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev. This underlines the stark reality that there has been a total lack of sympathy and empathy in the West after the attempted coup in Turkey. The Erdogan-Putin meeting was mostly about pragmatic topics of bilateral cooperation, the lifting of Russian sanctions, tourism, and so on.

The tension between Russia and Turkey after a Russian fighter jet was shot down worried NATO greatly, and a rapprochement is to be welcomed in that sense. But you think the West should have done more to reassure Erdoğan?

It is not just about Erdoğan. I think the West should do more to reassure Turkey that it is part of the Western camp. Itʼs one thing to assure Erdoğan. But the more important message is to Turkey, because at the end of the day, Turkey is much bigger than Erdoğan. This is where the gap is; even people who are not necessarily pro-government believe that the West has not done enough to demonstrate that Turkey has and should continue to have a Western orientation.

Indeed, there haven’t been that many Western visits to Ankara lately …

US Vice President Joe Biden visited at the end of August. Before that there’s been one visit by a junior UK minister and one by the state secretary of the German Foreign Office, Markus Ederer – not quite the level expected by Ankara. I think the West would be in a more credible position had it not only supported the government, but also parliament. If European leaders do not want to be seen with Erdoğan, at least they could have sent parliamentary delegations.Is it too late for that now?

No, not at all. Parliamentary delegations would go beyond the government and embrace parliament, which was bombed on the night of the coup. It shouldnʼt be too difficult to organize these trips in support of parliamentary democracy in Turkey. In fact, it would be politically relatively easy for Western politicians. And if the West wants to remain credible and retain the moral high ground in order to be able to criticize some of the governmentʼs post-coup measures, it can only do so if it also clearly takes a principled position and is critical of the coup attempt. If it does not do so, then the criticism will continue to fall on deaf ears because then the West will be – legitimately, I believe – considered hypocritical. If you don‘t stand for a rightfully elected government, then whatever you say after that tends to be weakened.

NATO has sometimes been more able to cooperate with Turkey than the EU. Does this also apply in this post-failed coup situation?

You are absolutely right: Turkey is in a different place in NATO by virtue of the fact that it is a NATO member. But the NATO relationship is quite difficult right now because of the souring of the relationship with the US. There is a widespread belief in Turkey, and that goes far beyond the government, that the US was behind the coup, or at least the US knew about it in advance and didnʼt tell the Turkish government. This has implications also for NATO. Then there is the fact that almost half of all Turkish generals have already been sacked, and some of these people had NATO positions. The head of the Third Army Corps, which is part of the NATO Rapid Response Corps, has been implicated in the coup. So obviously there is quite a bit of volatility around the NATO relationship today. What that means longterm is difficult to say right now.

The reluctance of the West to engage with Turkey right now of course has to do with the way Erdoğan has been fighting the coup and the measures he has put in place in the aftermath. And there is skepticism regarding the alleged role of the Gülen movement; Ankara’s accusations sound a bit overdone to Western ears.

You’re right. One of the difficulties today is this wide perception gap inside Turkey and outside about the role, the power, the influence of the Gülen movement. Today in Turkey many people believe that the Gülenists were behind the coup. Every day you have a former Gülenist appearing on TV, explaining to the Turkish public how he and his fellows infiltrated state institutions and military …

… which reminds one of the Stalinist show trials, when the accused had to declare that yes, they had been part of a huge conspiracy …

Yes, but it is a fact that this is the atmosphere that Turkish people get exposed to every day in the media. It is also something that the government firmly believes, especially Erdoğan. In that sense there is quite a gap between how Turkey views the Gülen movement and how the rest of the world views it. And this is already creating complications, in terms of Turkey ʼs relationship with the rest of the world, particularly the US where Gülen resides. Ankara has already started the process to have him extradited to Turkey. But it wonʼt stop there, because this movement is present, I think, in around 160 countries in the world, which means that Turkey will now have to make an effort to essentially press those governments to go after the Gülenistsʼ infrastructure in all of those countries, which includes schools, fundraising front organizations, and so on. This will be a longterm, complicated, and, in a way, unwelcome burden on Turkeyʼs foreign policy.

Gülen and Erdoğan were very close allies once …

That’s absolutely right. After the failed coup President Erdoğan issued an apology for having failed to understand the true nature of this movement. But of course, in any normal country, this wouldn’t suffice to explain and justify a political alliance that lasted a decade. I doubt more will happen in the case of Turkey, but the apology was certainly a start.

How likely is it that the coup has basically been remote-controlled by the Gülen movement in the US?

I think it is still quite likely, and I base this on the timing of the coup. Because the only explanation for the timing of the coup that makes sense is that most of the Gülenists in the military were going to be purged in August at the military council. Thatʼs the only explanation in terms of the timing of the coup. So I think it certainly was very much a Gülen-led coup.

What do you expect to happen next? Will Erdoğan take this chance to establish himself as an autocratic ruler?

Right now we are living through extraordinary times: a state of emergency has been declared, and therefore some of the measures the government is taking are not subject to the usual checks and balances. The government said it wants to end the state of emergency in three months, so that will be a critical test of how soon Turkey will normalize – if they are able to lift the state of emergency within three months, then that means that the checks and balances will return, which would work against further infringements of rights. So for the time being, I am reserving judgment as to how things will unfold.

How could the gap you describe be narrowed, especially with the EU?

The Turkish government’s strong anti-Western rhetoric has become a real obstacle to its efforts to get its message across in the West at a time when this is urgently needed. I think the Turkish government is making legitimate arguments, for instance against the teaching of Gülenist thought in schools, but because of its past combative, non-cooperative rhetoric toward the West it has difficulty now convincing the West about the nature of its arguments. Now the government is trying to find a middle road to get this message across.

What has to happen on the Western side?

The West should start with reassuring Turkey. Then it can build a moral platform to criticize some of the developments, but it has to start with reassurance.

This interview was originally published by the Berlin Policy Journal.