The arrest in August of liberal theater director Kirill Serebrennikov, on charges of alleged fraud and embezzlement, is redefining the Russian government’s relationship with art and culture. According to the new unwritten rules, any artist receiving funds from the federal budget is expected to tacitly pledge loyalty to the Kremlin.

The issue of what sort of cultural products the government should finance has become very controversial over the past five years. For example, in 2014, Russia’s Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky said: “The one thing I don’t see the point of, is making films with [state] funds that not only criticize but vilify the elected government.”

With Serebrennikov under house arrest, several individuals repeated similar messages. A publication by prominent film critic and journalist Maria Kuvshinova and the statements of film director Nikita Mikhalkov both urged the cultural elite to honorably forgo the privileges associated with state funding and work without taking government money.

Of course, the idea of privately financed films and plays is nothing new in Russia. For decades, the political environment has forced cultural figures and members of the intelligentsia to choose between state privileges and artistic freedom. Previously, this choice was rather personal—often construed as a matter of moral conscience. Now, given the loud and demonstrative way the Serebrennikov case is being pursued, the state is no longer recommending compliance but demanding it.

Ever since Soviet Russia rejected Stalinism in the 1950s, public discussions about culture gave Russians the impression that individuals—not the state—were in charge of determining the boundaries of public freedom. The divide between what was permissible or forbidden was not always clear. In some cases, this level of ambiguity gave individuals flexibility and seemed to be proof of personal liberty.

For many, Russians’ ability to read about, listen to, or even quietly discuss all sorts of previously forbidden topics became a point of national pride. Across film and art, and even among government officials, newfound cultural liberalism was counterpoised with an increasingly unattractive standard of what constituted a model Soviet citizen.

However, it soon became apparent that the state was still drawing its own lines—the 1964 trial of poet Joseph Brodsky and the 1965–1966 trial of Andrey Sinyavsky and Yuly Daniel were examples of these dividing lines between official art and unofficial art. The message was that only the state could recognize an individual as a poet, actor, or dancer.

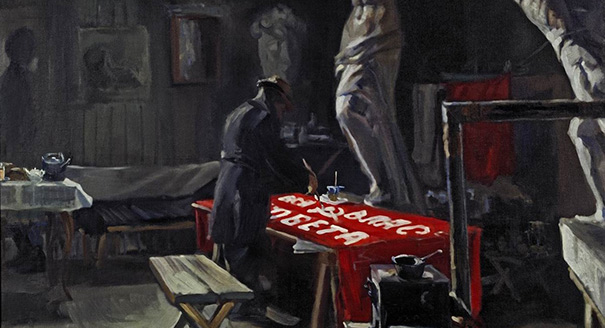

“Unofficial” culture did not have this power, and any “titles” that it granted did not carry any weight. By design, this status quo forced artists to voluntarily operate in tandem with the state. You could make art on your own, but it would be cushier, safer, and more lucrative to do so under the red banner.

Why, exactly, in 2017, is the Russian state pursuing new rules to govern a system where private and public culture are already de facto divided? For the Kremlin, this important move tacitly articulates a new concept of loyalty. The public nature of Serebrennnikov’s show trial is a statement that everyone must understand the new rules without the need for the authorities to explicitly state them.

As part of a plan for the upcoming six-year presidential term, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Education, and other institutions are working on building a new official culture for the Russian state. The “red banner” no longer exists; meaning there is no longer a state ideology. Patriotism, likewise, cannot reliably serve as a rational basis for separating Russians from one another. So the Russian state has chosen a more tangible parameter—the federal budget.

Given that the system of government financing in culture is so convoluted, any theater director could find himself in Serebrennnikov’s place. Alas, this is the trade-off for receiving state benefits—constant supervision, fear tactics, and adherence to impossible regulations. Under such circumstances, many filmmakers are increasingly unwilling to accept state funds; not just for ideological reasons but also because of how cumbersome the system can be. This year, eight of the twelve movies being shown at Kinotavr, Russia’s leading national film festival, were privately financed.

The masterminds of the new system expect unofficial culture to account for about 5 percent of Russia’s culture industry—on par with the share of small business in the country’s GDP. This doesn’t mean that non-state culture will be completely banished from the official sector. But any recognition of unsanctioned representatives by the Kremlin will likely be a form of self-serving praise directed at Western audiences, akin to the way Russian film director Andrey Zvyagintsev was recognized for winning at the Cannes Film Festival.

This new Russian model of managing culture is not new. There are two obvious examples in Iran and China. Both countries have independent artists who occasionally find themselves at Cannes or the Venice Film Festival. In their home countries, the line between official culture and the underground is clear, as are the rules of the game. The relationship was defined long ago.

Now Russia has defined this relationship as well. In the long run, this is likely to produce an official culture that will be stylistically homogenous, lacking artistic freedom, and not particularly engaging. The underground and counterculture will be vibrant, but neither safe nor lucrative. Repressive and restrictive laws still exist, and no one doubts that they will be used more frequently to target unofficial culture products. One way or another, the state sets the limit for freedom, and it will certainly be easier to control unofficial culture once it has been cordoned off.

In short, the Kremlin’s new message on cultural policy is clear—“if the government pays the piper, it calls the tune.”

.jpg)