Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

{

"authors": [

"Christophe Jaffrelot",

"Kalaiyarasan A"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "ctw",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "SAP",

"programs": [

"South Asia"

],

"projects": [

"India Elects 2019"

],

"regions": [

"South Asia",

"India"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy",

"Economy",

"Civil Society",

"Religion"

]

}

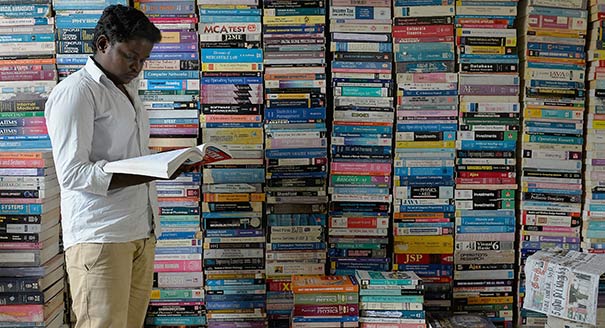

Source: Getty

Karnataka offers an alternative model state based not only on growth, but also on the closing of social and religious gaps, in contrast to the socio-economic, caste, and communal polarization which prevail in western and northern India.

Source: Indian Express

In a recent speech at the Mahatma Gandhi Stadium, Bangalore, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah presented Karnataka as a better model state than Gujarat because of its capacity to attract investments (Rs 1.50 lakh crore per annum against Rs 40,000 crore). He also used today’s standard metrics of development by saying that Karnataka’s growth rate was above the national average (8.5 per cent against 7.1 per cent).

But there are other criteria of human development: Karnataka has contained social inequalities on at least one count, the closing gap between the OBCs, SCs and Muslims on one hand, and the dominant castes on the other hand — and in this domain it has been more effective than many states, including Gujarat.

According to the Indian Human Development Survey, in 2011-12, the annual per capita mean income of the OBCs represented 89 per cent of that of the dominant castes — Lingayats and Vokkaligas — in Karnataka. In Haryana, Gujarat and Maharashtra, it represented only 49, 50 and 78 per cent.

Interestingly, the relative affluence of the Karnataka OBCs — in 2011-12 they earned more than the Gujarat OBCs, Rs 26,264 as annual per capita mean income, against Rs 25,488 for the Gujarat OBCs — was not due to job reservation. Only 12 per cent of the Karnataka OBCs got salaried jobs, against 15 per cent for the Gujarat OBCs. Karnataka OBCs benefited more from another dimension of the positive discrimination programmes: Quotas in education.

Indeed, the percentage of graduates among the Karnataka OBCs is slightly above that of the dominant castes, 4.8 per cent against 4.6 per cent. Gujarat OBCs lag behind, with only 2.1 per cent of the state OBCs reaching the graduation level, almost five times less than the dominant castes.

In spite of atrocities, Dalits lag less behind dominant castes in Karnataka than in Gujarat in socio-economic terms. While they got 68 per cent of the annual per capita income of the dominant castes in Karnataka, they received only 54 per cent of it in Gujarat in 2011-12 (against 57 per cent in 2004-05).

Muslims also do well in Karnataka as compared to some other states. In 2011-12, the annual per capita mean income of the Muslims was 74 per cent of that of the Hindus in Karnataka while it was 31 per cent in Haryana, 62 per cent in Gujarat and 73 per cent in Maharashtra. The average Muslims earned Rs 20,473 in Karnataka while they earned only Rs 18,864 in Gujarat. That was partly due to the fact that a section of backward Muslims has been included in the reservation list. The percentage of graduates among Muslims was 2.8 per cent in Karnataka, while it was just 1.6 per cent in Gujarat in 2011-12. Today, Karnataka is also offering a range of scholarships to all the minority communities, which benefitted over 14 lakh students.

These contrasts between Karnataka and Gujarat reflect diverging public policies and political trajectories. In the late 1970s-early 1980s, Gujarat and Karnataka were among the pioneering states in terms of reservations. But Madhavsinh Solanki had to give up his policy in 1985 due to Patel-led demonstrations and no government revisited them, whereas Karnataka, with ups and downs, made the legacy it had inherited from Devraj Urs fructify.

While the Gujarat Congress let the KHAM coalition desintegrate, the Karnataka Congress rebuilt what is today known as AHINDA, a Kannada acronym for Minorities, Backwards and Dalits. Siddaramaiah, who is himself an OBC from the Kuruba (shepherd) caste, has committed to increase, if reelected, reservations beyond the 50 per cent cap the judiciary has imposed in every state except Tamil Nadu.

The court would prevent that, but this promise may strike a chord even beyond the Backwards and Dalits. Indeed, the creative manner in which Karnataka has dealt with reservations has resulted in the inclusion of segments of the dominant castes, mainly Vokkaligas, among the OBCs: Vokkaligas who have studied in a school in a rural area are eligible for the OBC quota.

Here again, Karnataka could offer a model to Gujarat, Maharashtra and Haryana, three states where dominant castes are asking for reservations because of the critical situation of their rural segments. While some Vokkaligas benefit from reservations, Lingayats are following another route by asking for recognition as a religious minority.

Beyond reservations, Siddaramaiah has implemented a slew of welfare measures. On August 16, 2017, Indira Canteens were launched to serve subsidised food to the lower sections in towns and cities, a scheme akin to Amma Canteens in Tamil Nadu. The canteens provide breakfast, lunch and dinner at subsidised rates and attract daily wage labourers, drivers, security guards, and others.

In 2017, the state introduced the Ksheera Bhagya scheme, which offers milk to 37.52 lakh children aged from 6 months to 6 years, 5 days a week. Eggs are distributed twice a week to 14.85 lakh children aged between 3 and 6 years in anganwadis. This scheme, besides improving child nutrition, has helped reduce the school dropout rate. The Mathru Poorna scheme, also introduced in 2017, offers nutritious hot cooked meals to pregnant women and lactating mothers.

In 2017, too, the Anna Bhagya scheme provided free rice through the Public Distribution System to people below the poverty line, a relief to the rural poor as the state was reeling under severe drought. In June 2017 President Pranab Mukherjee signed the Karnataka Transparency in Public Procurement (Amendment) Bill, 2016, which provides reservations for SC/ST contractors in government contracts up to Rs 50 lakh.

Whether the social dimension of the Congress’ programme will be sufficient to win the coming elections remains to be seen. Certainly, the party has sent positive signals to the relegated Dalit jatis by promising them sub-quotas within the SC category, but the new alliance formed by the JD(S) and BSP may well make inroads among the Congress’ Dalit vote bank.

The state’s tradition of shifting from one party to the other in each election may help the BJP, especially if the latter succeeds in communalising the campaign and taking the state by storm with Narendra Modi as the chief campaigner.

Whatever the results of the elections, Karnataka stands as an alternative model based not only on growth, but also on the closing of social and religious gaps, in contrast to the socio-economic, caste and communal polarisations which prevail in western and northern India. But Karnataka may exemplify here what is true of the South at large.

This article was originally published in the Indian Express.

Former Nonresident Scholar, South Asia Program

Jaffrelot’s core research focuses on theories of nationalism and democracy, mobilization of the lower castes and Dalits (ex-untouchables) in India, the Hindu nationalist movement, and ethnic conflicts in Pakistan.

Kalaiyarasan A

Kalaiyarasan is faculty at the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, New Delhi.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

Domestic mobilization, personalized leadership, and nationalism have reshaped India’s global behavior.

Sandra Destradi

The recent record of citizen uprisings in autocracies spells caution for the hope that a new wave of Iranian protests may break the regime’s hold on power.

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

Internet service providers can facilitate internet access but also draconian control.

Irene Poetranto