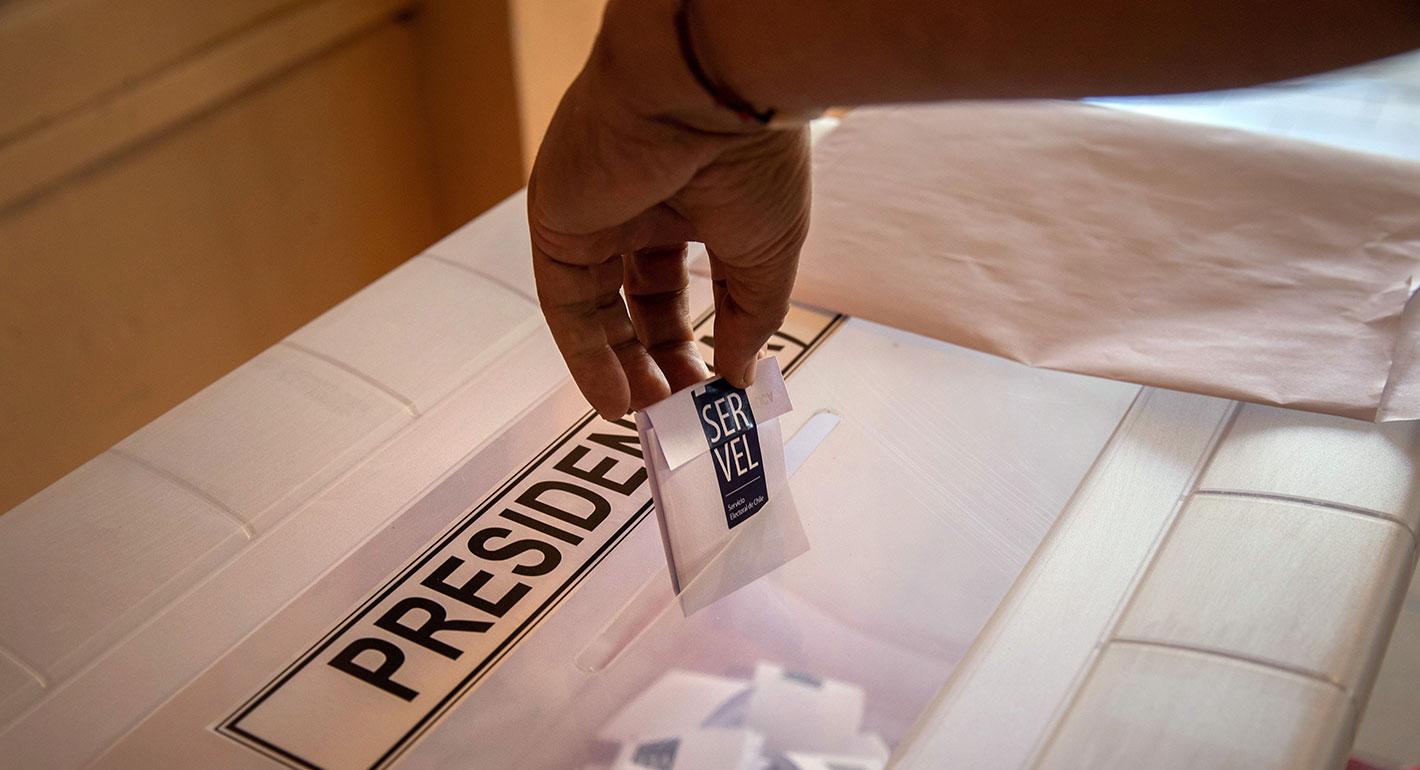

The first round of Chile’s presidential election on November 21 saw far-right candidate José Antonio Kast come in first, with about 27.9 percent of the vote. In second was thirty-five-year-old Gabriel Boric, the young, left-wing politician and former student leader, who received approximately 25.8 percent of the votes. In a sign of how disenchanted Chileans have become with traditional political elites, candidates from the center-right and center-left alliances—which have taken turns governing the country since its redemocratization in 1989—came in fourth and fifth place, respectively, behind even Franco Parisi, another antiestablishment candidate who came in third with 12.8 percent of the vote. The political center, which has dominated in Chile for the past few decades, gained less than one-fourth of the votes.

Latin American regional experts have been watching Chile’s election more closely than any other contest in Latin America this year. Long seen as a model for liberal reformers across the region, Chile ranks seventeenth in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index and was traditionally seen as exceptionally stable. Yet the country made global headlines in 2019 when months of mass protests and political upheaval, caused by discontent about inequality and bad public services, led to the creation of a constituent assembly to replace the country’s dictatorship-era constitution. The constituent assembly is still ongoing and is generally seen, despite the uncertainty it has created, as a blueprint for how to respond to civil unrest and channel outrage. In a region ravaged by the pandemic, growing inequality, political instability, and democratic backsliding, the post-2019 period in Chile was considered a cause for hope and optimism—even though the protests revealed that the country’s problems were far greater than outside observers had previously assumed.

Yet the 2021 presidential election suggests that the days of Chile’s moderate and consensus-based style of politics are over. Instead, the country seems poised to experience an extremely polarized showdown during the December 19 runoff between two men whose respective visions for the future of the country are diametrically opposed—Kast, restoration and Boric, transformation.

The Candidates

Kast, an ultraconservative father of nine who opposes immigration, abortion, same-sex marriage, and political correctness, has projected himself as the mano dura (tough-on-crime) candidate and has expressed his admiration for the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. In Kast’s view, the social upheaval that rocked Chile in 2019 was essentially a law-and-order problem. He has argued that center-right politicians, such as former president Sebastián Piñera, carelessly gave in to radical leftist demands—such as accepting the process of writing a new constitution, a move that Kast has resolutely opposed. Inspired by former U.S. president Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro—though somewhat less strident—Kast has argued that in the upcoming runoff, Chileans have the choice between “freedom and communism.”

Specifically, Kast has proposed to cut taxes, reduce the role of the state, and deploy the military to deal with frequent conflict between the Indigenous Mapuche community, landowners, and law enforcement in Araucanía, a region in southern Chile. In a parallel to Trump’s vision for the U.S.-Mexico border, Kast has seized upon a growing wariness among Chileans about immigration and has proposed digging a border trench to keep out migrants, particularly those from Venezuela.

Boric, on the other hand, is a progressive left-wing leader who has framed the election as one of fear against hope, with a vote for him being a vote for hope. He has argued that it is time to bury Chile’s neoliberal model and prioritize the fight against inequality, one of the key causes of the wave of protests in 2019. Boric’s project involves proposals to increase the role of the state and the social welfare system, overhaul Chile’s pension system, and focus on environmental sustainability—a controversial topic in a country where mining is responsible for half of the country’s exports as of 2019.

Boric’s focus on issues like LGBTQ rights and the legalization of abortion (which is outlawed with the exception of a few specific cases) sets him apart from most other traditional left-wing leaders in the region, most of whom embraced social conservatism. Boric is known for his pragmatism and willingness to distance himself from Latin America’s authoritarian leaders on the left, such as Nicaragua’s dictator, President Daniel Ortega—but Boric’s alliance includes Chile’s Communist Party, which controversially backed Ortega’s recent sham elections. Concerns that Boric would not be able to fully control the more radical wing of his alliance, if he were to take office, were systematically exploited by the Kast campaign.

The Voters

In every election since Chile’s redemocratization, whoever obtained the highest number of votes in the first round also won the runoff—so for now, Kast is largely seen as the favorite. But a lot will depend on how the 46 percent of voters who supported candidates who did not make it into the runoff will react. Just like in Brazil in 2018, moderate conservatives (a large share of the voters in most Latin American countries) will have to decide whether to back a far-right politician with a questionable commitment to democratic rule or whether to support a leftist progressive who does not seem to pose a threat to democracy but whose sweeping proposals are bound to scare many voters who prefer the status quo.

Another important question is how the nearly 13 percent of voters who supported Parisi—a businessman who lives in the United States and who did not set foot in Chile during the campaign, participating only in virtual debates—will behave. However, few of his supporters can be expected to side with Boric, given Parisi’s economic conservatism. In the same way, much of the runoff’s outcome will depend on the roughly half of the population that did not vote at all in the first round. Voting has been optional in Chile since 2012, and elections since then have been shaped by high abstention rates.

Upcoming Challenges

This complex scenario is even more unpredictable given that the new president will have to govern while the constituent assembly is continuing to draft a new constitution, which citizens can either accept or reject in a referendum next year. If Kast is elected, one of the main political dynamics in the coming year will be the antagonism between Kast and the constituent assembly, given the assembly’s large number of independent and left-leaning representatives. In theory, the next president’s mandate could even end early if, for example, the constituent assembly opted for, and the public approved, a transition to a parliamentary system.

More broadly speaking, however, Chile’s success will depend on the capacity of Chile’s next president to establish a functioning dialogue with those who supported the losing candidate. Chile’s Senate is evenly divided between the right and left, and whoever wins will have to cobble together alliances in the National Congress to govern. Since neither Kast nor Boric would have a majority, whoever is elected would have an incentive for moderation given the need to work with other parties to govern.

If the president is unable to reach across the aisle, the country may fall victim to the ills so common across the region: political paralysis, destructive polarization, and a growing vulnerability to populist saviors. Given Chile’s mature democracy, stable political institutions, and vibrant civil society, it is uniquely well-placed to address its challenges in a constructive way. If it fails, it is hard to imagine that any other Latin American country could do better.