Last year’s UN climate negotiations in Baku, Azerbaijan, were billed as the finance COP, with the hope that states would agree to a new and more ambitious way of funding climate actions around the world. Previous years have had other emphases—such as 2023’s loss and damage COP (Dubai) or the 2022 Africa COP (Egypt)—but finance is always a part of the conversation.

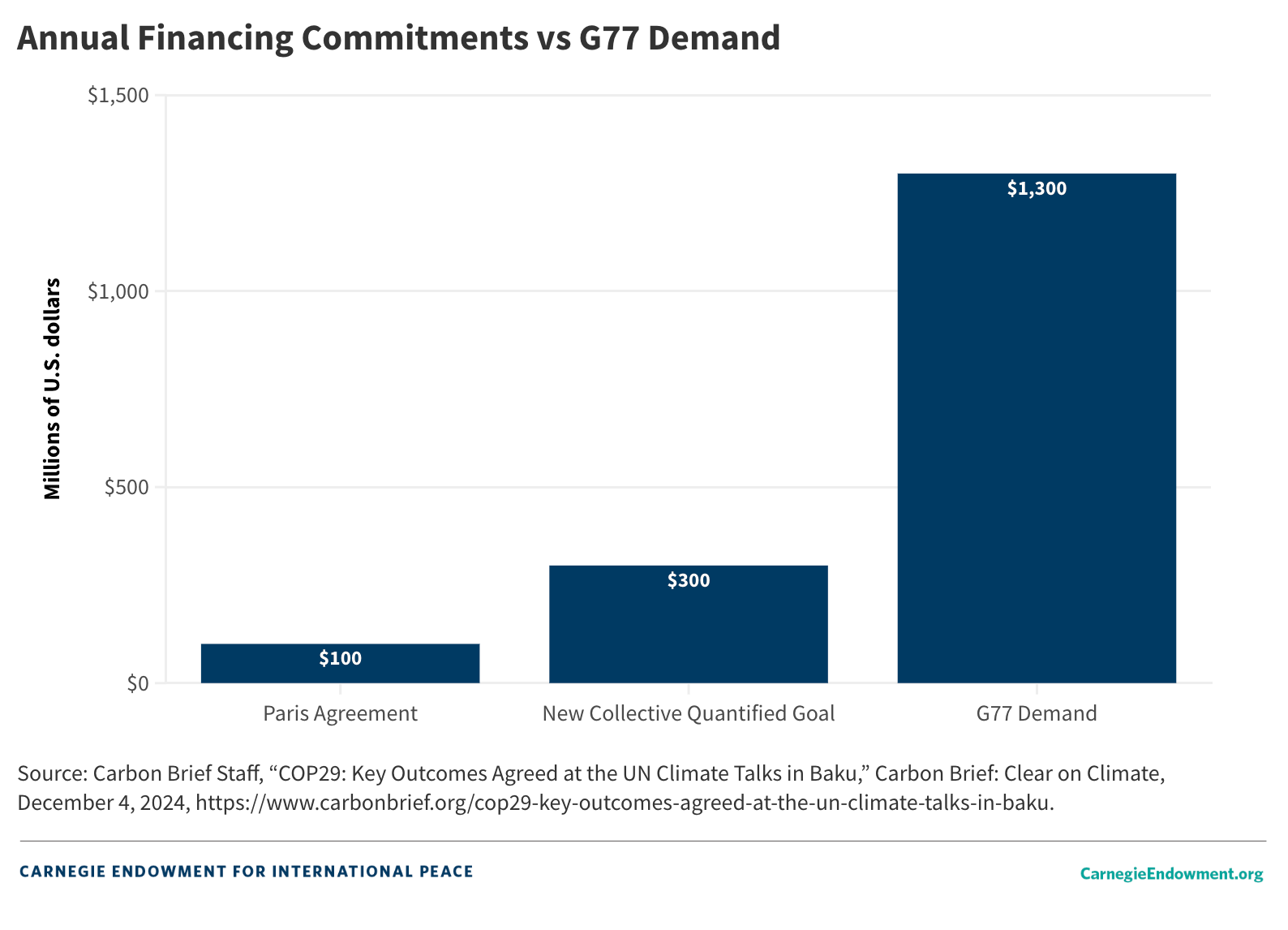

The delegates at COP29 were tasked to agree to the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG) as an update to the Paris Agreement’s target of $100 billion per year. However, states failed to meet the $100 billion goal ever since, with the sole exception of 2022.

What happens to the COPs when the climate negotiations are all about the money? A political economy lens can help us understand what happened with the Baku Pact.

Discussions were narrowly focused on the size of funding commitments—or the “quantum,” as negotiators like to say. The G77 and China started this COP by demanding $1.3 trillion each year to address the needs of climate mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damages. Donor countries balked at this number, instead suggesting $250 billion per year by 2035. The hotly contested, final agreement set at least $300 billion per year by 2035 from developed countries and calls on “all actors” to work together to scale up the financing to developing countries to $1.3 trillion by 2035.

But this focus on scale obscures harder questions about the winners and losers within that funding—and what is left out. For example, should states put money toward stopping future climate change or coping with the current climate disasters? Should funding come from Western governments as grants or private banks as loans?

Mitigation Versus Adaptation

In 2022, the ratio of North-South climate finance for mitigation versus adaptation was about 70:30. It is a political choice to prioritize mitigation over adaptation: Global North countries care more about mitigation (reducing emission), while the Global South often pushes for adaptation (dealing with current impacts of climate change). In part, this is because countries in the Global South are more vulnerable and hurt more by the current and future impacts of climate disasters. But it is also because countries in the Global South are worried that mitigation efforts could slow their economic growth or prevent development. Many poorer governments argue that they are willing to commit to mitigation goals as long as there are real commitments by rich countries to help fund their transitions to clean energy.

The Baku Pact does not specify if the $300 billion is for mitigation or adaptation—rather it affirms that finance should strike a “balance between adaptation and mitigation.” But balance does not mean equal.

Public Versus Private

Another big question was the type of funding: Would the Baku Pact deliver concrete commitments of public finance or general references to mobilizing private finance for climate action? Public finance includes government funding through public and multilateral institutions, while private finance comes from private banks or foreign direct investment and comes with different types of strings.

Again, the final agreement from Baku went general, stating that the $300 billion goal should be “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.” This means that some countries will count private funding for their contributions to the goal.

Besides the public-versus-private debate, poor countries also demanded that climate finance be channeled through the UN climate funds (Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, Loss and Damage Fund, and so on) because multilateral funds are supervised by the UN, transparent, and democratically accountable. In contrast, rich donor countries use bilateral finance to favor their allies, benefiting some regions over others, and without the same requirements for transparent reporting. The Baku text decides for “at least triple annual outflows from those Funds from 2022 levels by 2030 at the latest with a view to significantly scaling up the share of finance delivered through them.” This is strong language and promises to grow the UN funds if the EU and other donor states follow through—however, the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump is not likely to increase climate funding or contribute to UN funds.

Grants Versus Loans

Countries also are worried about the balance of grants versus loans. The Global South pushed for grants because they would not be required to pay them back, while loans—even concessional loans—would balloon national debt for poor countries already struggling with high debt burdens. These countries are also concerned about accessing climate loans because many of the most heavily indebted countries do not qualify for private loans and sometimes struggle with concessional loans from multilateral development banks (MDBs). The Bridgetown Initiative, led by Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados, has been pushing for reforms of MDBs and other international financial institutions, particularly the criteria used by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and credit rating agencies. Many analysts agree that grants cannot meet the global scale of need for climate finance, and so some mixture of loans and public-private partnerships will be necessary. MDBs would be key to mobilizing the additional private financing.

The Baku Pact nods toward this debate by urging MDBs to “eliminate conditionalities for access” and invites financial institutions to use a range of tools including “non-debt-inducing instruments.” One of the weakest parts of the text merely suggests “considering shifting their risk appetites” and “considering scaling up highly concessional finance.”

This is why developing countries were outraged by the Baku Pact: instead of concrete commits for public grant-based funding, the text waves at every kind of financial tool with a relatively modest “quantum.”

Who Pays?

Finally, the Baku Pact does not answer who pays for climate action. One of the institutional legacies within the UN process is that the Kyoto Protocol committed developed countries (Annex I) countries to take actions to reduce emissions, including providing funding for less developed countries. The countries defined as developed (and thus expected to donate) still reflect 1990, when the classification was first established, despite major changes in the global economy since. For example, China’s GDP per capita was $905 (adjusted to constant U.S. dollars in 2010) in 1990 but in 2023 was $12,174. China is still defined within the UN climate change framework as a developing country and is not expected to be a donor to climate finance.

In Baku, the EU and United States pushed hard to redefine which countries should be donors, but that did not make it into the pact. Instead, the text “encourages developing country Parties to make contributions, including through South–South cooperation, on a voluntary basis.” This acknowledges that China and other non-Western countries are increasingly becoming donor countries while reaffirming that their contributions are voluntary. For example, China has become a major voluntary donor to climate finance to the tune of $4 billion per year from 2013-2022. In fact, China contributed more to climate finance than the United States under the Trump administration. But donor countries (even China) are happy to continue with voluntary pledges (instead of mandatory contributions) because they do not want to be held accountable if or when their national governments fail to meet their promises.

The 2024 finance COP went over by a full day, with negotiations going late into the night and resulted in protests by civil society and angry speeches by the least developed countries. The Baku Pact sets out an overall target of $300 billion per year for climate finance—tripling the previous goal—but the agreement doesn’t resolve some of the most important questions of about who pays for what, where, and how.

The legacy of Baku might be that the scale of the climate finance increases, but it will not resolve these thornier questions which are ultimately about climate justice and global inequality.

.jpg)