When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

{

"authors": [

"Isaac B. Kardon"

],

"type": "testimony",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"China and the World",

"Dynamic Security Risks in Asia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"China",

"East Asia",

"Asia",

"United States",

"North America",

"Central America and the Caribbean",

"South America"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"Economy"

]

}

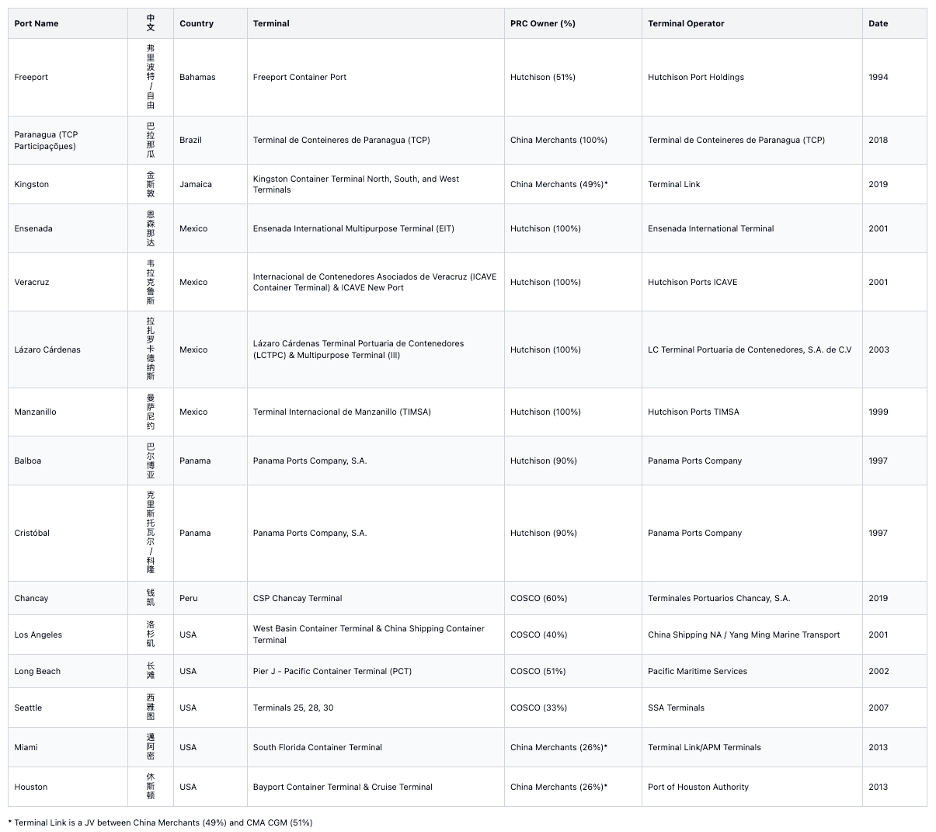

Chinese companies have established full or partial ownership over terminal leases and operating concessions in seven countries in the Western Hemisphere: the Bahamas, Brazil, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and the United States.

Testimony before the United States House of Representatives, Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security, 119th Congress

Chairman Giménez, Ranking Member McIver, and members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for this opportunity to testify before you today. My testimony addresses “strategic port investments” of Chinese firms in the Western Hemisphere, and analyzes their implications for national security. Those investments most relevant to the Committee’s jurisdiction and oversight authority are five joint ventures involving PRC enterprises in cargo terminals in U.S. ports on the Pacific and Gulf coasts. Another ten current PRC port investments in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) may also bear on port operations and maritime infrastructure security within United States, and are therefore material to this analysis.

Chinese companies have established full or partial ownership over terminal leases and operating concessions in seven countries in the Western Hemisphere: the Bahamas, Brazil, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and the United States.1 PRC firms have also made previous, unsuccessful attempts to invest in port terminals in Argentina (Ushuaia), Brazil (São Luis, São Francisco), Canada (Québec), El Salvador (La Unión), and Panama (Isla de Margarita – Colón).2 Two state-owned enterprise (SOE) conglomerates owned and administered by the central government,3 China COSCO Shipping Corporation Ltd. (“COSCO”) and China Merchants Group Ltd. (“China Merchants”) are responsible for eight of these investments – including in all five of the U.S. ports. One Hong Kong-based (HK) private corporation, CK Hutchison Holdings Ltd. (“Hutchison”), and its multinational portfolio companies, hold the other seven in the hemisphere. Together, these “Big Three” Chinese port operating companies account for 81% of the total PRC port investments overseas (77 of 95), and generally own minority stakes in the local SOEs and private enterprises involved in other projects.

In comparison to PRC port investments across Europe, Africa, and Asia, Chinese firms have established a relatively small presence in the Western Hemisphere. The 15 ports in the region (cf. 36 in Asia and 23 in Europe) account for 16% of all PRC overseas ports. Chinese companies initiated only five of the port projects in this hemisphere since 2013, demonstrating the lower priority Beijing places on the region, as well as its delayed marketing of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and financing to LAC countries. PRC firms partially own terminals in five U.S. ports: Houston, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Seattle.

Annex A, Table 1 shows details about PRC-invested port terminals in the hemisphere.4

Port of Los Angeles (LA): China Shipping Group (merged with COSCO in 2016) formed a joint venture in 2001 to operate the West Basin Container Terminal (WBCT) in the Port of LA. COSCO owns 40% of the JV through a local subsidiary, the Taiwanese firm Yang Ming owns 40%, and Ports America owns the remaining 20%. The lease on this terminal was extended in 2021 for an additional nine years, to 2030. China Shipping operates 3 of the 14 berths at the terminal; the rest are operated by Yang Ming, with stevedoring services provided by Ports America. These operations account for roughly 20% of the twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) throughput at the port. Additionally, China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping visited a China Shipping berth (number 100) at WBCT in February 2012 (when he was PRC Vice Chairman), accompanied by California Governor Jerry Brown and LA Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.6 At that time, a planned expansion of the terminal was entering its final stages after facing lawsuits over its environmental impact. The terminal was ultimately approved in 2019 by the Port of LA Harbor Commission, though this approval was based on new requirements for mitigation measures.7

Port of Long Beach (LB): COSCO partnered with Stevedoring Services America Marine (SSA) in 2002 to lease and operate Long Beach, Pier J. They took over a lease vacated by the Danish shipping and logistics firm, Mærsk. Their JV, Pacific Maritime Services LLC (PMS), is a private, Delaware-registered corporation that continues to operate the Pacific Container Terminal. COSCO is the majority shareholder (51%) through its New Jersey-based subsidiary COSCO Terminals North America. Decisions by the JV board require an “affirmative vote of at least 70% of the ownership shares of the members,” meaning COSCO does not hold an effective majority. SSA operates the terminals and COSCO provides cargo volumes and shipping services.8 In 2018, COSCO acquired the Hong Kong shipping firm Orient Overseas (International) Limited (OOIL); however, a subsequent CFIUS review required the divestiture of OOIL’s wholly-owned Long Beach Container Terminal (LBCT) in order to complete the transaction.9

Port of Seattle: Two COSCO subsidiaries hold a collective 33.33% stake in Terminal 30 at the Port of Seattle through a JV with SSA Marine in place since 2007. As in Long Beach, SSA is the operator, and COSCO’s role as a minority shareholder is to drive cargo traffic through the terminal. According to port officials, there is also a COSCO contract or service agreement in place for container logistics at Terminals 25 and 28.

Port of Houston: In 2013, China Merchants acquired 49% of the public shares of the French firm CMA CGM’s port operating subsidiary, Terminal Link.10 China Merchants therefore holds a proportional equity stake in the joint venture between Terminal Link Texas (51%) and Ports America (49%) at the Bayport Container and Cruise Terminals.11 The Bayport container facility is part of a larger Houston port complex that is the leading overall handler of domestic and foreign waterborne tonnage in the country, and which conducts 34.4% of its container trade with the PRC, its largest foreign market.12

Port of Miami: This South Florida Container Terminal (SFCT) is a joint venture between Terminal Link (51%) and A.P. Möller-Mærsk Terminals (49%), so China Merchants owns roughly 25% of the equity and receives proportional revenues from port throughput. Terminal Link and APM Terminals operate berths 110 and 99 in this modern, upgraded container terminal, with access to all major U.S. and LAC markets. As in Houston, China Merchants holds equity but also has no managerial or operational role in the terminal.13

Excluding the United States and Mexico, there are six PRC-invested ports in the rest of the hemisphere. Among them, those in Brazil, Panama, and Peru rate special attention as “strategic port investments” due to their geographic positions and connections to major markets and resources.

Panama:14 The government of Panama granted two 25-year concessions to operate ports on either side of the Panama Canal in January 1997 to Hutchison’s Panama-incorporated subsidiary, the Panama Ports Company, S.A. (PPC). These concessions were automatically extended in 2021, without competing bids, for the period 2022 to 2047.15 PPC holds a 90% stake in the concessions for the ports of Balboa (on the Pacific) and Cristóbal (on the Atlantic), with 10% retained by the Panamanian government. The contract preserves Panama Canal Authority (PCA) control over the canal and its approaches.

“Panama Law No. 5” establishes the statutory terms for Hutchison’s concession for the “development, construction, operation, administration and management of the port terminals for containers, RO-RO, passenger, bulk cargo, and general cargo in the ports of Balboa and Cristóbal.”16 The law explicitly states that the contract is subject to the jurisdiction of the PCA (and therefore, to that of the government of Panama):

By virtue of Article 310 of the Political Constitution that creates the Panama Canal Authority, and grants it powers and responsibilities, and also by virtue of the close connection between the Authority’s activities and the operation of ports adjacent to the Panama Canal, the contract contained in this Law is approved subject to none of its clauses being interpreted in a way that conflicts with the powers, rights and responsibilities conferred to the Canal Authority in the cited constitutional provision or in the law that organizes it, especially regarding the use of areas and facilities, control of marine traffic and pilotage of vessels transiting through the canal and ports adjacent to it, including its anchorages and dry docks. (Annex X, Article 2)

Hutchison PPC exercises substantial control over terminal operations at the ports of Balboa and Cristóbal – but, like the other foreign port operators in the country, the firm must coordinate with, and remain subordinate to, the government’s sole control over Canal operations.17 For a ship to navigate the interoceanic route, PCA regulations dictate that it must be approved and assigned a space in the transit queue by the Panama Canal Maritime Traffic Control Center.18 These regulations also define the scope of the “Canal” to include “the waterway itself, as well as its anchorages, berths and entrances; lands and sea, river, and lake waters; locks; auxiliary dams; dikes and water control structures, as established by the Organic Law.”

Hutchison PPC port operations on either side of the canal collectively moved an estimated 3.8 million TEUs in 2024, representing nearly 39% of the total throughput across five ports adjacent to the canal. This is less than the total throughput of the Colón port complex on the Atlantic side, where terminals operated by the American firm SSA Marine and the Taiwanese firm Evergreen moved over 4.7 million TEUs over the same period, accounting for 49% of the cargo volume. Another port facility on the Pacific side at the former American Rodman Naval Base in Balboa, Panama International Terminals, is operated by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), and mostly accounts for the remaining 12% of throughput. Individually, however, the largest single (sub)port is the Manzanillo International Terminal at Colón, where the consortium led by SSA Marine (including PSA as well as Panamanian investors) accounts for nearly 30% of the total throughput in 2024 (down from 31% in 2023 and 32% in 2022).19

A separate Panama port concession was awarded to the private PRC firm Landbridge Group in 2016, which partnered with central SOE China Communications Construction Company Ltd. (CCCC) to build, operate, and own a new terminal on Isla de Margarita in the Colón Free Trade Zone.20 With a 5 million TEU designed annual capacity and bold ambitions to expand to a 11 million TEUs, this terminal would be the largest in Latin America. However, the Panama Maritime Authority revoked the concession in June 2021, claiming that the Landbridge-led consortium was out of compliance with contractual terms for failing to meet required levels of investment and employment of Panamanians. U.S. infrastructure investment firm Notarc Management Group subsequently partnered with the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) to acquire the concession, rebranded as Panama Canal Container Port (PCCP).21 Landbridge is currently fighting to reinstate its concession, refusing to join Notarc’s “sham arbitration” in Panama, and pursuing arbitration in Delaware district court and litigation for injunctive relief in Barbados (where Landbridge Holdings, Inc. is registered).22 The project remains mired in controversy, but Notarc and MSC are reviewing the designs to resume construction on the 40% developed Isla de Margarita port.23

Peru: COSCO’s first foray into Latin American ports is a 2019 joint venture with Volcan Compañia Minera S.A.A. (Volcan) to develop a deep-water port at Chancay, 70 kilometers north of Peru’s capital, Lima. COSCO holds 60% of the concessionaire, Terminales Portuarios Chancay S.A. (TPC), with remaining shares held by Volcan, a Peruvian mining company producing zinc, lead, and silver.24 In 2021, COSCO and Volcan signed an agreement with Peru’s National Port Authority (APN) granting TPC exclusive rights to build and operate the facility.

After the wide authorities granted to TPC under this concession met public scrutiny, APN cited an administrative error and filed a lawsuit to annul the exclusivity clause. COSCO threatened to withdraw and seek international arbitration. Peruvian authorities acquiesced, dismissing the lawsuit in June 2024, then passing a legislative amendment that gave APN the authority to grant exclusivity rights for a period of 30 years.25 Separately, in October 2024, COSCO filed for a protective injunction in the Civil Court of Chancay against Peru’s Supervisory Body for Investment in Transportation Infrastructure for Public Use (Ositran), challenging its jurisdiction and oversight over its private and exclusive project.26 The Chinese firm asserted that it was not properly considered a “service provider” regulated by Ositran, demanding exclusive rights to control intermediary actors that usually provide port services like towing or piloting ships, transshipment and storage of goods, supply of fuel, and ship waste management.27

These legal proceedings were still underway during Xi Jinping’s visit to Peru for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC) in November 2024, when he inaugurated the Chancay mega-port (remotely from Lima) alongside Peru’s president, Dina Boluarte. The PRC is Peru’s largest trading partner, and Chancay is expected to significantly reduce shipping times and increase shipping volumes between South America and Asia.28 Boluarte lauded the port’s potential to contribute 1% to Peru’s GDP in 2025 and transform the nation into a “world-class technological and industrial center” and a major hemispheric logistics hub. To date, COSCO’s lawsuit is still pending in Peruvian courts, and continues to generate controversy, but the port is operational and under COSCO control.29

Brazil: China Merchants launched its first port project in Latin America in 2017, acquiring 90% of the Terminal de Contêineres de Paranaguá (TCP) 30-year lease agreement for the port of Paranaguá.30 The managing director of China Merchants Port Holdings, Bai Jingtao, described Brazil as “China’s most important strategic partner in the region;”31 other PRC corporate leaders welcomed the chance to “put Paranaguá on the map of the Belt and Road Initiative.”32 By 2020, China Merchants moved to acquire the remaining 10% of the port lease from Brazilian minority investors, and then later that year, transferred 22.5% of their 100% shareholding to China Portugal Development Fund and the China LAC Development Fund. These Chinese state development funds were recruited into the project to “make use of their institutional coverage and in-depth understanding on Africa and Portuguese-speaking countries, to give full play to their capital operation capacity and assist the development and operation of the projects.”33

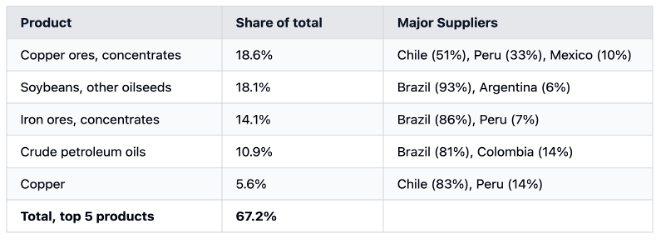

Paranaguá holds special appeal for Chinese firms because it is Brazil’s largest port for agriculture exports, and the PRC is the world’s largest agriculture importer. In the context of the burgeoning trade war with the U.S. in 2018 – during which China levied retaliatory tariffs across a range of American agricultural products – this new and expanded terminal provided necessary capacity for surging PRC imports of Brazilian soybeans, beef, pork, cotton, tobacco, oilseeds, and a range of other goods. The composition of China’s agriculture trade changed dramatically in this period to favor Brazil over the U.S., with the American share of Chinese agriculture imports declining from 21% to 12% from 2016 to 2018, while Brazil’s share increased from 18% to 26% over the same period.34 China Merchants signed a letter of intent with Portos do Paraná, the state port authority, to extend their concession another 25 years and undertake capacity expansion at the port.35 As trade tensions with the U.S. intensify, this port and its growing capacity will enable continued diversification of China’s trade in agriculture (as well as critical minerals), moving away from the United States and further consolidating its position as South America’s leading trade partner.

Other LAC ports: Alongside Panama, Peru, and Brazil, PRC firms have also established port ownership and operations in the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Mexico. Of particular note are the four large, wholly-owned Hutchison port facilities in Mexico (as well as an intermodal logistics hub and a shipyard) that Hutchison management describes as “strategic ports on both coasts.” China-Mexico trade volumes rose 34.8% year-on-year in 2023, another 28% in the first half of 2024, and are likely to continue their breakneck growth with further U.S. tariffs.36 This trade diversion to Mexico affords China with several advantages in trade wars with the United States, including the chance to diversify supply chains, leverage reduced tariff schedules under the U.S.-Mexico-China Agreement (USMCA), and access emerging markets in Latin America. (See Annex A, Table 2)

The descriptions in the prior section lay out key characteristics of the most significant and strategic ports owned and operated by PRC firms in the hemisphere since these investments began in Panama, in 1997. They may implicate homeland security and regional maritime security through two main pathways: (a) port facilities and associated infrastructure used as platforms for People’s Liberation Army (PLA) military operations in the region, and (b) they introduce a range of physical and digital operational risks and vulnerabilities for U.S. ports and transportation systems.

Chinese companies’ hemispheric port investments are appropriately considered to hold both strategic and commercial value for the PRC. In the first instance, this is because virtually all cargo ports can facilitate both trade and miliary operations. Ocean ports with deep harbors (i.e., the projects which PRC firms generally pursue) can generally accommodate the massive cargo vessels employed by the contemporary shipping industry as well as the largest capital ships in any naval fleet. Such ports are essential for the conduct of international trade and commerce, granting the nation’s merchant fleet regular access to foreign markets and resources. Additionally, navies have historically been entrusted with the mission to protect these assets and commercial flows from disruption by military or irregular threats and to prevent raiding of their nation’s commerce. For a naval fleet, these facilities allow for sustained operations far from home shores – and in close proximity to major maritime chokepoints and vital sea lines of communication (SLOCS). Defense and, if possible, control of these critical geographies has historically provided strategic advantage to nations capable of building and properly employing sea power.37

Chinese strategists and leaders have internalized these Mahanian ideas in their efforts to build maritime power and achieve “national rejuvenation.”38 In this respect, Beijing’s approach resembles that of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, an early champion of Mahan’s vision of sea power.39 Both for the Washington of the early 1900s (and perhaps again today) and for Beijing over the last two decades, control over ports (and canals) and the SLOCs connecting them became core elements of national maritime strategy. As the central nodes in the transoceanic trade and production networks, ocean ports are essential to the stability of China’s maritime trade-oriented economy and provide the “maritime lifeline” for its overall political system.40 Since the beginning of the 21st century , Beijing has implemented concerted industrial policies to develop immense scale in domestic and foreign port terminals, shipbuilding, shipping, ship owning and leasing, crane manufacture and delivery, container manufacture and leasing, shipping insurance, brokerage, and more.41 With state support, leading PRC enterprises have successfully pursued extraordinary horizontal and vertical integration across global transportation and logistics sectors. By most measures except for naval capability, China is now the world’s leading maritime power.

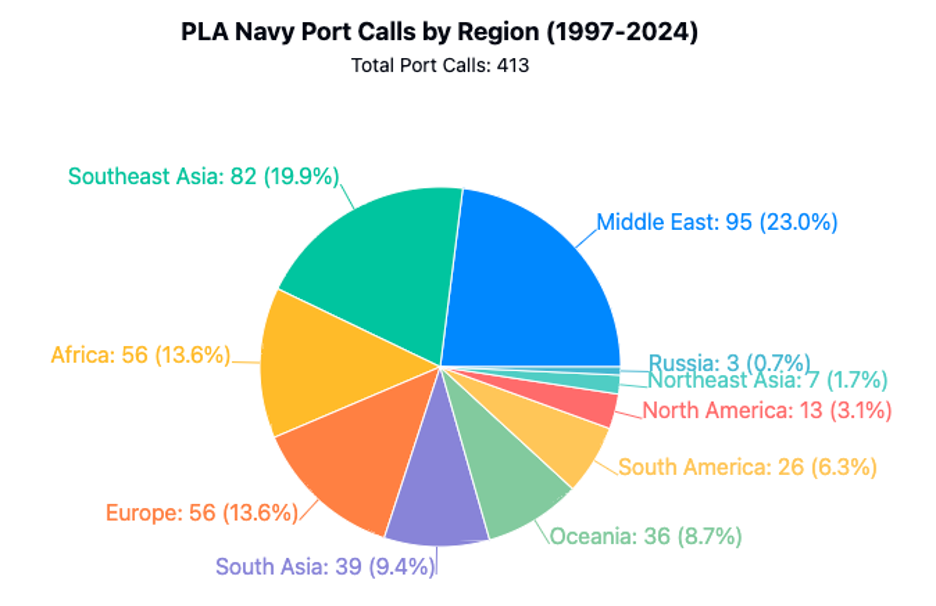

China’s naval force, the Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), has made increasing use of port facilities abroad to expand its areas of operation, and to conduct gradually more sophisticated missions overseas. Protecting China’s overseas economic interests became an explicit PLA mission since 2003, and was formally adopted in 2015 as one of eight “strategic tasks” for the nation’s increasingly modern and capable armed forces.42 Employing a single formal naval base, established in 2017 at Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, the PLAN operates extensively across every ocean and continent.43 They are demonstrating that even without dedicated military facilities or basing arrangements, any PLAN vessel can call on a port to refuel, resupply, rest its crew, and make at least minor repairs.44

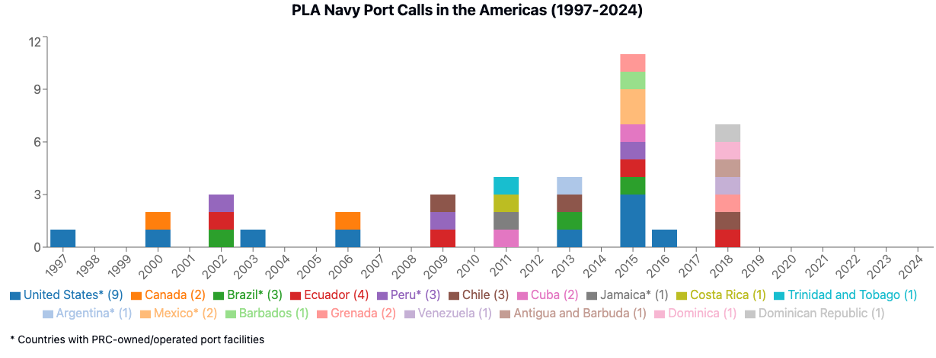

Chinese forces have not deployed regularly to this hemisphere. However, the PLA’s extensive pattern of naval port calls, senior-level military visits, and exercises across the globe demonstrate a latent capability to project significant power across oceans and continents. To date, these activities have been concentrated in East Asia and the Indo-Pacific region; but ports in the Western Hemisphere have also provided limited logistical and likely intelligence support for PLAN operations.45Annex B details these patterns of activity, but several observations stand out:

The Figures in Annex B show a Chinese military force that is comparatively absent from the hemisphere, with no port calls whatsoever within the past seven years. There has been no observable pattern of calling disproportionately in countries where Chinese firms own or operate ports (denoted with asterisks in Figure 2) – with the notable exception of the United States. However, the Chinese-invested ports in LA/LB, Seattle, Houston, and Miami are not plausible platforms for any aggressive or otherwise unapproved PLA operations (except for probable intelligence collection and surveillance activities).47 The material risks from Chinese assets at U.S. ports concern cyber disruptions and other non-kinetic operations addressed below. Overall, this pattern of military activity and diplomacy indicates a relatively modest approach by China to naval power projection in the Americas.

However, the port facilities in Panama, while never visited by PLAN vessels, are of greater concern from a military-strategic standpoint. While these terminals do not grant Hutchison any operational control or authority to regulate transits through the Panama Canal, their geographic position makes them consequential. The United States relies disproportionately on the efficient functioning of the canal, which provides the most efficient route between the U.S. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Panama Canal Authority figures indicate that in 2024, 74.7% of all cargo moving through the canal has a U.S. port as its origin or destination; PRC-origin or -bound cargos came a distant second at 12%, highlighting the clear asymmetry in the great powers’ dependence on the canal.48 While PRC firms operate ports in the vicinity of other major chokepoints, including the Malacca Straits, Hormuz Strait, Bab el-Mandeb, and Suez Canal, the threat of severing (or simply delaying) Panama Canal access is more problematic from a homeland security perspective. By comparison to the geostrategic stakes at Panama, U.S. trade and military freedom of navigation do not face major risks in distant theaters – including in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, where more far more capable groups of Chinese naval and joint forces routinely operate.

There is little possibility for Hutchison or any Chinese user of their facilities to use Balboa or Cristóbal as a fortress to project military power into the canal zone. There is also no requirement to make a port call at a PPC facility in order to transit the canal; and even if a port call is necessary for cargo operations or replenishment, there are multiple alternative port terminals operated by American, Singaporean, and Taiwanese firms adjacent to both Pacific and Atlantic approaches. Transiting vessels and cargos can be observed or surveilled easily from almost any vantage (including by live-feed cameras offered by the Panama Canal Authority).49 The more worrisome potential vulnerability is that these approaches could be denied in a crisis. In order for American forces to transit from the Atlantic to rush to the Western Pacific in a crisis over Taiwan, for example, the time sacrificed to delay or denial at the Panama Canal could be the difference between operational success and failure.

Operating a port adjacent to the canal, however, does not afford any unique capability for the operator to obstruct safe transit through the waterway. As witnessed during the Ever Given crisis in the Suez Canal in 2021, a large cargo ship can intentionally or unintentionally impede all transit through narrow chokepoints for days or weeks. Scuttling a ship in the lock system or, more aggressively, emplacing naval mines in the harbor are other methods that could seize up a maritime chokepoint for an indefinite period. These and other methods create perhaps unavoidable vulnerabilities that do not arise from China’s access to facilities adjacent to the canal. Chinese-owned or -flagged ships make regular transits through the canal and could readily be tasked with such a mission, should Beijing consider it advisable.

The correlation of forces in the Western Hemisphere, however, makes it inadvisable for Chinese leadership to test their military capabilities against the U.S. in or around the Panama Canal. Huge and enduring American advantages in combat power and readiness afforded by its proximity and presence in the region provide ample reason for Beijing to reject the idea of fighting symmetrically or kinetically in this hemisphere. Even efforts to interfere with the flow and positioning of U.S. forces is likely to be more costly than constructive, given close U.S. defense cooperation with the Panamanian government, which includes a bilateral ship boarding agreement (through the Proliferation Security Initiative) that would enable early detection and assertive action if there were plausible indicators and warnings of a threat to the canal’s security.50 U.S. military intervention in the hemisphere is also credible and not without precedent, particularly in Panama.51 Further, after the reversion treaties restoring the Panama Canal Zone to Panamanian sovereignty, the U.S. Senate reserved a right to intervene again “in the event of armed attack against the canal, or when, in the opinion of the President, conditions exist which threaten the security of the Canal.”52

The ports of Chancay in Peru and Paranaguá in Brazil are more remote from U.S. direct national security concerns. Even if Lima or Brasilia were to permit significant PLAN access to those facilities, their geography poses a lesser threat to American strategic interests. Any PLA status of forces or basing agreement with another nation in this hemisphere, whether in a PRC firm-owned port or not, would be interpreted in Washington as a serious threat. From Beijing’s strategic vantage, then, there is very little to be gained by posturing itself to project marginally more combat power from a theater in which the U.S. military fields far superior capabilities and enjoys ready access. Testing America’s long-standing exclusivity about hemispheric security would be a risky and counterproductive deviation from China’s clear strategic imperives, which remain anchored in the Western Pacific.53

Chinese port investments in the hemisphere are unlikely to pose direct military threats to America’s homeland security nor challenge its regional military predominance. However, they expose certain physical and digital vulnerabilities in U.S. maritime infrastructure and transportation networks that warrant heightened scrutiny and coordinated mitigation efforts. Building on the technical assessments by senior cybersecurity and maritime operational security experts from the Department of Homeland Security and Coast Guard in previous testimony before this Subcommittee, the following assessments draw on subsequent events and further consider the level and effect of party-state control over China’s private firms and SOEs.54

The most probable risks posed by Chinese companies’ port investments in the United States arise from PRC-made equipment and software nested within maritime infrastructure and transportation systems. By introducing so-called “Smart Ports” and their associated digital technologies and processes into critical infrastructure across the hemisphere, Chinese firms have installed a range of sensors, modems, software, and digital back doors that may readily enable intelligence collection and covert surveillance – and also hold some potential to disrupt vital operations at U.S. ports.55 Certain well-documented exploits, like “Salt Typhoon,” serve as cautionary examples, highlighting the potential for destructive or disruptive attacks within the existing threat landscape.56

Yet without direct observation, it is impossible to assess or predict the degree to which Chinese intelligence services and other state actors may exert positive control over PRC enterprises’ equipment and software. Technical methods exist to remotely monitor and access the information and communication technologies of PRC firms operating overseas, in compliance with PRC regulations; these tend to enable broad surveillance and require data sharing for national security purposes. There can be no certainty about the multifarious uses state actors may find for these data (e.g., industrial espionage, intelligence collection, or cyber exploitation). However, the growing pervasiveness of Xi Jinping’s “comprehensive national security outlook” means that this is a fast-moving target: firms that were once relatively free to operate more or less in line with foreign laws and norms are gradually losing that already-limited autonomy.57 SOEs are already under close supervision and management, and will be responsive to political objectives. Firm leadership has been force-fed a comprehensive diet of Xi Jinping Thought on cybersecurity and learned that: “There is no national security without cybersecurity.” This securitization has proceeded in waves of new laws and policies that demand invasive “data localization” and disclosure in order to “protect” commercial and personal information and communications networks. 58

Even for private multinational firms based in Hong Kong, the business and political environment has rapidly come to resemble the situation of overt control over the private sector and civil society that prevails in mainland China. While even five years ago a firm like Hutchison could exercise a reasonably high degree of autonomy, company leaders are quietly but quickly growing pragmatic about obeying Beijing’s dictat. Meanwhile COSCO, as a central SOE, “assumes greater responsibility for political directives and priorities” than do private firms with leaders whose networks can “obscure company affairs from external [and party] scrutiny, or push back against administrative superiors.”59 Hutchison and its international stakeholders would surely struggle against attempts to deploy the PLA for any hostile purposes, thus weaponizing its global network of infrastructure assets and investments. Despite Hutchison’s greater remove from state control than its SOE counterparts, the firm observably does not deny berths to PLAN vessels that request to call. 60 In the normal course of diplomatic affairs, of course Panama would be entitled to reach its own sovereign decision about whether to authorize any foreign naval visit.

A. China’s presence in U.S. ports presents unquantified but material risks to critical maritime and transportation infrastructure – but unwinding it recklessly will do more harm than good. PRC firms’ partial ownership or operation of a small number of U.S. port terminals should not be the primary national security concern in this line of inquiry. These joint ventures fall under strict federal and local jurisdiction and supervision. Auditing and, if necessary, terminating, renegotiating, or forcing divestiture of port concessions is not likely to mitigate the more compelling risks associated with Chinese technologies present across a range of physical and digital transport and communications systems. Surveillance cameras, cranes, logistics software, shipping containers, and other technologies are embedded components of port systems and often necessary for stable operations – and not only at PRC firms’ port terminals. Sharper attention and stricter guidelines should be applied to mandatory cybersecurity screening across U.S. port networks, coupled with targeted investments to produce indigenous or friend-shored alternatives. Tariffs will be insufficient (and likely unnecessary) to wean U.S. industry off of risky PRC equipment at any price point, given the unavailability of substitutes and the long time-lags to purchase, manufacture, and install heavy machinery like ship-to-shore cranes.

B. The Panama Canal is an enduring and vital national security interest, and the Panamanian government is our essential partner in its protection. In order to maintain the efficient functioning of the waterway for both American and international commerce and free navigation, our governments should better coordinate efforts to ensure the neutrality and security of the Panama Canal. American leaders should stimulate private capital to invest in upgrading the canal system and adjacent port terminals, work cooperatively to improve the booking and auction system for transit slots, assist the audit process of the PPC concession, and share resources and intelligence that will enable Panamanian authorities to better monitor Chinese enterprises’ activities across a range of port and canal infrastructure, including bridges, rail, road, and communications systems throughout the canal zone.

C. Chinese military control over ports in the Western Hemisphere is unlikely and runs contrary to Beijing’s strategic objectives in the region. The correlation of forces in the hemisphere is balanced heavily in U.S. favor from a military standpoint. Any power projection the PLA may generate from access to deep-water ports is limited by its appetite for overt military rivalry in America’s backyard. Those military activities that do occur are more likely to be associated with diplomatic outreach and intelligence collection, neither of which warrants forcing Latin American countries to choose a great power patron. A more effective strategy will be to reinforce America’s strong defense partnerships across the region and cooperate more deeply with friendly countries to address their primary national security concerns. Beyond arms sales and military exercises, additional emphasis should go towards non-traditional security assistance like law enforcement equipment and training. These efforts will bear fruit for homeland security concerns about illegal immigration and drug trafficking.

D. National maritime security requires global maritime partnerships. China has achieved extraordinary scale and growing sophistication in its maritime industries, building a merchant and naval fleet that dwarfs our own, and driving unprecedented maritime trade volumes through its global network of ports. To compete with Chinese maritime power, Washington will need to pursue ambitious measures to restore our previous strength in the sector. Even with heroic industrial policy and private sector cooperation, there is no short- or even medium-term option to compete port for port or ship for ship with the PRC. But fortunately there is also no need to do so because American allies and partners in places like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and across Europe are sophisticated and capable shipbuilders, port operators, infrastructure developers, and equipment manufacturers. Appropriating funds and establishing authorities towards these ends should be priority legislative efforts, in particular the creation of a Maritime Security Advisor and Board to coordinate and oversee whole-of-nation maritime strategy.

Table 1: Chinese firms’ ownership and operation of ports in the Americas

Data Source: Kardon and Leutert, “Appendix for “Pier Competitor.”

Table 2: Latin America & the Caribbean Top Exports to China (2020-2023)

Data Source: Rebecca Ray, Zara C. Albright, and Enrique Dussel Peters, “China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin,” University Global Development Policy Center (2024).

Figure 1:

Data Source: Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, “Chinese Military Diplomacy Database v4 (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University, August 2024)

Figure 2:

Data Source: Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, “Chinese Military Diplomacy Database v4 (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University, August 2024)

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

German manufacturing firms in Africa add value, jobs, and skills, while benefiting from demand and a diversification of trade and investment partners. It is in the interest of both African economies and Germany to deepen economic relations.

Hannah Grupp, Paul M. Lubeck

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

And how they can respond.

Sophia Besch, Steve Feldstein, Stewart Patrick, …