The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets

{

"authors": [

"Michael Pettis"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"Carnegie China Commentaries"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"China’s Reform Imperative"

],

"regions": [

"China",

"East Asia",

"Asia"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

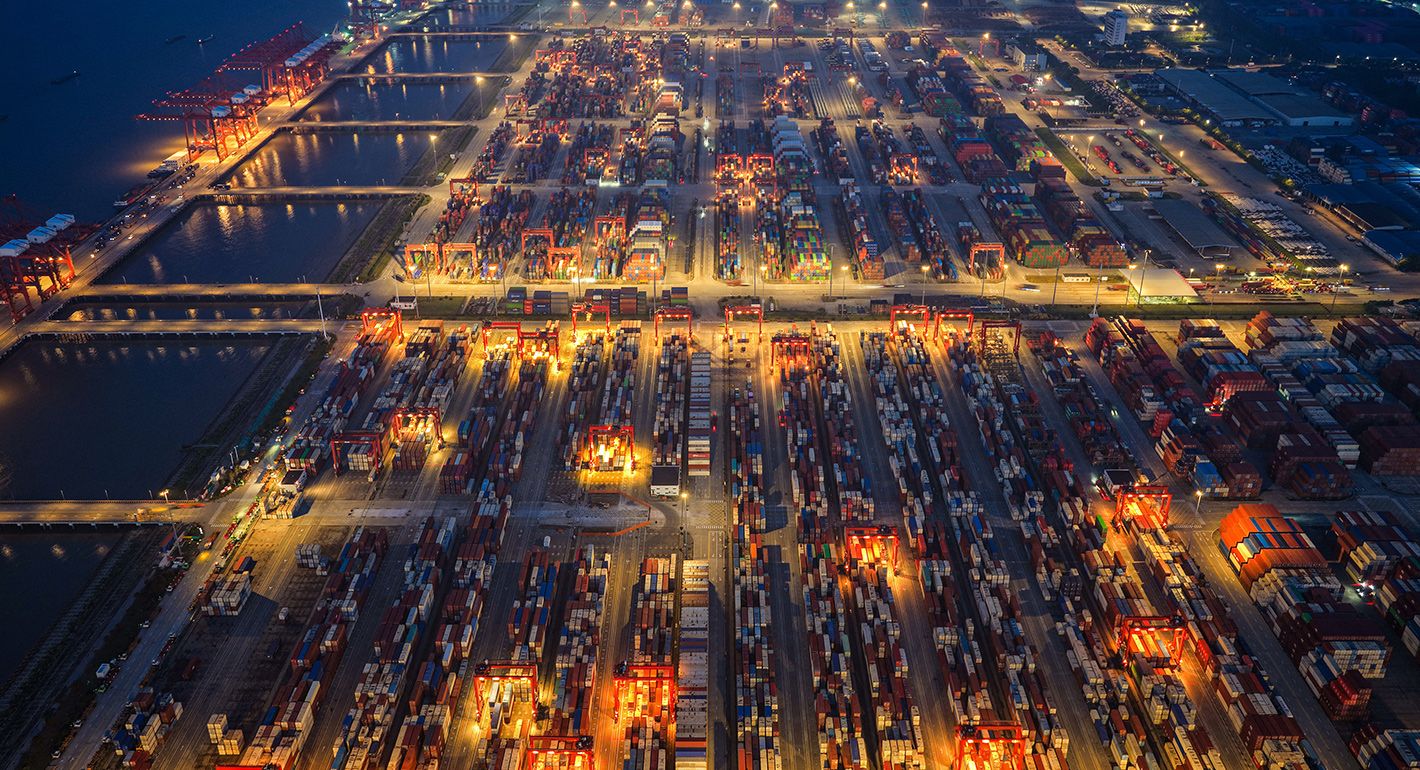

Source: Getty

GDP growth means something fundamentally different in China than in most countries.

This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

Every few weeks or months, institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and major global banks update their forecasts for China’s GDP growth, adjusting them in response to new data. In 2025, this cycle of revisions is again following a familiar pattern: projections are being raised or lowered based on monthly data releases, shifts in global trade dynamics, or policy signals from Beijing.

Already in early 2025, analysts have revised their estimates several times. At the beginning of the year, most banks expected that China’s GDP growth in 2025 would come in well below the GDP growth target of 5 percent. But these expectations changed in late March after Chinese leadership made ambitious economic pronouncements during the annual Two Sessions governmental meetings in March. As the Wall Street Journal reported, the banks HSBC, ANZ, and Citi upgraded their forecasts for China’s GDP growth to 4.8 percent, 4.8 percent, and 4.7 percent, respectively—up from previous estimates of 4.5 percent, 4.3 percent, and 4.2 percent.

Other institutions such as Morgan Stanley, BBVA, and Nomura, though still somewhat conservative, also nudged their predictions upward. The United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development expected growth above 4.5 percent, bringing estimates in line with the Chinese government’s official target.

By mid-April, sentiment shifted again as the trade war took central stage. Among the most pessimistic, according to Bloomberg, was UBS, which cited new U.S. tariffs as a reason for forecasting growth as low as 3.4 percent. In response to generally gloomy growth predictions, Chinese Finance Minister Lan Fo’an reiterated the government’s commitment to meeting the 5 percent target, promising more proactive macroeconomic measures.

Expectations changed again, however, after the United States and China announced a trade deal in Switzerland last week, with most banks immediately raising their GDP growth projections. Some banks raised it by as much as 0.6 percentage points.

These extremely large fluctuations in growth predictions pose a deeper question: are GDP growth predictions the best lens through which to view China’s economic performance? Is it meaningful to assume that a country’s expected growth for a given year can really change by so much, and so quickly?

The likely answer is no. In China, GDP growth targets are not set in response to economic conditions but rather to politically determined goals. Unlike in most market economies, where GDP growth is the result of aggregated private and public sector decisions that vary according to changes in underlying conditions, China’s growth target is a policy directive. It serves as an input into government planning rather than a neutral forecast.

The Chinese government sets a growth target each year and then ensures that the economy achieves it, even if doing so requires aggressive state intervention. If organic growth falls short, state-owned enterprises, local governments, and certain favored private firms—especially in strategic sectors such as artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, and clean energy—are directed to step in. These actors operate under soft budget constraints, meaning they essentially have access to unlimited credit and are not subject to traditional bankruptcy risks.

In contrast, most activity in most other economies occurs under hard budget constraints. Firms and investors pursue projects only if they expect a return that justifies the risk. Unproductive investments result in losses, and repeated poor performance can lead to bankruptcy. This financial discipline ensures that growth, when it occurs, is typically tied over the medium term to actual economic value creation.

But in China, where the government can command and subsidize investment, any GDP target can be met—at least in the short term—as long as there is available debt capacity and willingness to use it to fund soft-budget activity, however unproductive. The problem is that this kind of growth can raise the headline GDP figure without necessarily improving the economy’s long-term productivity or resilience.

Chinese policymakers are not unaware of this issue. In fact, they have increasingly emphasized the importance of “high-quality” growth—a term used to distinguish between growth driven by real demand and productivity versus growth driven by excessive borrowing and construction. In 2024, the Qiushi journal (the Communist Party’s top theoretical outlet) once again underscored the need to shift away from overreliance on debt-fueled investment toward growth rooted in domestic consumption.

But because this is widely understood, when global analysts raise or lower their GDP forecasts, they are probably signaling a change in the expected quality of growth, not its quantity. This distinction is crucial. Higher than expected consumer spending, higher business investment, or higher export activity should not imply that GDP growth will be higher. Rather, it suggests that the government will need to rely less on wasteful infrastructure or property investments to meet its growth target. The target stays the same—only the composition and quality of growth changes.

Given that China’s GDP is politically predetermined, forecasting GDP per se is less meaningful than forecasting the components of GDP. A better analytical approach would be to assume the 5 percent growth target will be met, as it always is, and to focus instead on how that growth will be achieved—through some combination of consumption growth, investment growth, and growth in net exports. To the extent that the outlook for high-quality growth—consumption, exports, or business investment—improves, rather than predict higher growth, analysts should predict the same amount of growth, but should stress that this growth would be of higher quality and more sustainable.

GDP growth can be broadly thought of as a composite of these three categories:

ΔGDP = ΔConsumption + ΔInvestment + ΔNetExports

According to official breakdowns, in 2024 the contributions to GDP growth in each of these categories were as follows:

This breakdown reveals a lot. Most notably, it implies that in 2024 the consumption contribution to GDP growth was unusually weak, especially compared to the pre-COVID-19 era when it typically accounted for around 60 percent of each year’s growth in GDP. Even a 60-percent contribution to GDP growth is too low—consumption will have to contribute 80–90 percent of GDP growth on average for the next ten years if China is to raise the consumption share of GDP by ten percentage points. (And as Liu Shijin, a former deputy director of the Development Research Center of the State Council, recently noted, the consumption share of China’s GDP is roughly 20 percentage points below a more “normal” level.)

In contrast to the very poor performance of consumption, the contribution of net exports to GDP growth in 2024 was extraordinarily high. Given the growth in consumption and net exports, in order to achieve the GDP growth target, Beijing had to ensure that investment contributed 1.2 percentage points (or 25 percent of GDP growth) in 2024. It did this by guiding banks to increase lending to favored industries and by directing local governments and special purpose entities to expand investment.

By comparing these three components of growth with expectations for this year, the evolution of the Chinese economy in 2025—and what it might imply for different sectors of the Chinese and global economies—can be analyzed. But this analysis should start with consumption and net exports, because these are the hard-budget components that Beijing cannot control. Investment, in this case, is the “residual” needed to achieve the growth target.

In that case, various paths that growth can follow in 2025 can be proposed, beginning again with the basic equation:

ΔGDP = ΔConsumption + ΔInvestment + ΔNetExports

And the various components can then be estimated. If analysts are less optimistic about consumption, they can perhaps project the following:

If they are, however, more optimistic about consumption and net exports, they might expect the following:

In both cases, China would achieve the GDP growth target it set in March, but it would do so in very different ways. The second scenario, for example, implies much higher-quality, and more sustainable, growth than the first and would result in a much smaller increase in the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. Among other things, it posits a bigger Chinese trade surplus, with all that implies for global trade tensions. It also posits that there would be reduced Chinese demand for the industrial commodities (for example, iron and steel) that are required to meet high levels of investment.

By focusing on these components, analysts can offer more meaningful insights into how China will meet its growth target and what kinds of policy or sectoral shifts will drive that outcome. And it’s possible to glean even more. If investment must rise to fill the gap left by weaker exports, in which sectors will this investment be directed? This will reveal even more about the components of Chinese growth and how it could affect the global economy.

The three main investment avenues in China are the property sector, infrastructure, and manufacturing. The property sector, long a pillar of Chinese growth, has been in crisis for years and has contributed negative growth in the form of a contraction in overall investment. It is unlikely to become a strong growth engine in 2025, though a stabilization may allow it to be less of a drag than in 2024.

Manufacturing investment remains high, but capacity is already stretched. With global overcapacity and rising tariffs, particularly on green technologies and electric vehicles, further acceleration in investment is possible, especially as that seems to be the preferred path of senior Chinese leadership, but it would almost certainly intensify global trade frictions.

This leaves infrastructure as a lever of choice. Beijing can rely on state-owned enterprises and local governments to build transport, energy, and digital infrastructure, funded by local bonds and state-backed banks. While this can temporarily boost GDP, it has diminishing long-term returns and exacerbates China’s debt load.

There is not enough information to precisely calculate how much the three main investment sectors contributed to growth in 2024, but these are my best estimates:

How will each investment component account for the amount of growth it must contribute in 2025 to achieve the GDP growth target?

Property investment will likely continue to contract in 2025, but by less than it did in 2024. The more meaningful question is whether Beijing will continue to pour resources into manufacturing investment, or whether because of worsening trade conflict and an increasing difficulty in selling the resulting increase in manufacturing production, Beijing will try to constrain growth in manufacturing investment. If the latter case, it would have to boost growth in infrastructure investment in order to reach the target. Notably, this may already be happening, as evidenced by the acceleration of railway projects this year; according to Xinhua, railway investment was up 5.3 percent in the first four months of 2025.

If consumption and net exports are assumed to collectively account for 70 percent of GDP growth in 2025, investment will have to account for 30 percent, or 1.5 percentage points. Here is one way this could happen, depending on the performance of the property sector:

In the above scenario, the growth in infrastructure spending in 2025 will keep pace with 2024—with all this implies for the prices of industrial commodities and the country’s debt burden—while China will ease off a little on relying on expanding its share of global manufacturing.

If, on the other hand, that consumption and net exports are assumed to collectively account for only 60 percent of this year’s GDP growth, and that this is partly balanced by a greater reduction in the negative contribution of the property sector, the outcomes could be as follows:

In this case, it would imply that Beijing has shifted its focus to a rapid expansion of infrastructure spending to achieve its growth target. The good news here is that this would be positive for industrial commodity prices, while the bad news is that it would imply an even greater deterioration in the country’s debt burden than seen in 2024.

None of this forecasting is especially easy, but estimating the performance of the components of GDP growth needed to achieve China’s growth target has several advantages over predicting and periodically changing the expected GDP growth rate for the year. First and most obviously, it allows analysts to recognize explicitly the role that GDP growth targets play in determining the performance of China’s economy every year. Second, it allows policymakers, investors, and researchers to track the quality of growth. And third, it helps identify how sectors of the Chinese and global economy will be affected by the composition of Chinese growth.

For example, if China leans heavily on infrastructure to hit its growth target, it will be good news for commodity exporters (for example, of copper and steel) but bad news for those focused on debt sustainability. Conversely, if consumption plays a stronger role, the resulting growth will be more stable and demand-driven—better for domestic retailers and foreign brands and for long-term economic health.

Barring a disaster, in which case all predictions will be off, China will almost certainly achieve its GDP growth target in 2025, which means that predictions by all the global financial institutions will converge to 4.8–5.0 percent by the fourth quarter of 2025. Lower predicted growth rates earlier in the year, in other words, are mostly meaningless as predictions.

But by acknowledging the GDP growth target and predicting growth on a sectoral basis, rather than through evolving GDP growth projections, analysts can focus on the components of that growth that will really influence the evolution of the Chinese economy. This will allow them to provide a better sense of how China will achieve its GDP growth target and what sectors will benefit most.

For example, it means there will likely be a tradeoff between more robust attempts to boost domestic consumption and heavier investment in infrastructure. Each has very different implications for investors, foreign manufacturers, and policymakers in China and abroad.

Each also has important implications for Chinese debt. If—as is almost certainly the case—fiscal policies that boost consumption have a higher multiplier than fiscal policies that boost investment (especially investment in infrastructure), the resulting rise in China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is likely to be higher if infrastructure investment takes a higher-than-expected role in achieving the GDP target and consumption and net exports take a lower-than-expected role.

The point is that GDP growth means something fundamentally different in China than in most countries. In the West, it is an output—a measure of economic activity that emerges from countless decentralized decisions—and so it makes sense to evaluate growth prospects continuously over the year and to change them as underlying conditions change. In China, GDP growth is an input—a number that is decided early in the year and then achieved through whatever intervention is necessary. For that reason, in China, it should not be evaluated and projected the same way as it is in the rest of the world.

The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez