- +2

George Perkovich, Jessica Tuchman Mathews, Joseph Cirincione, …

REQUIRED IMAGE

Talk Now, Talk Fast on North Korea

There are signs that the Six Party talks between the United States, North Korea, China, South Korea, Japan and Russia on North Korea’s nuclear program could soon resume. But holding talks while North Korea continues to expand its nuclear capabilities is like negotiating with a gun to your head.

There are signs that the Six Party talks between the United States, North Korea, China, South Korea, Japan and Russia on North Korea’s nuclear program could soon resume. North Korean leader Kim Jong Il told South Korea’s Unification Minister in mid-June that Pyongyang could return to the talks as early as July, if the United States treated his country with respect. If the talks are convened – still a major uncertainty - rapid progress on ending the nuclear crisis must be made. In the year since the talks were last held, North Korea has likely increased its plutonium stockpiles enough to build three additional nuclear weapons and its total arsenal could now include up to 11 nuclear bombs. Moreover, Pyongyang is currently refueling its weapons production reactor at Yongbyon and could at anytime restart the plant capable of producing a new nuclear weapon worth of plutonium per year.

Suspended since last June, and all but dead after North Korea’s February 10 announcement that it possessed nuclear weapons, the six party talks may have a new lease on life. The reasons for the opening are unclear, but regardless of the reasons the United States, China and other states should move quickly to convince North Korea to return to the table. And while talking is all well and good, talking at all costs and without results may be worse than no talks at all. Moreover, holding talks while North Korea continues to expand its nuclear capabilities is like negotiating with a gun to your head.

The Clinton administration rejected these circumstances in 1993 and 1994, with good reason and with good results. While Washington should not set preconditions for the resumption of talks, the list of near-term objectives for American negotiators must now include not only a commitment from Pyongyang to end its nuclear weapons program under effective and comprehensive monitoring but a freeze on all known nuclear activities, including plutonium production. Allowing North Korea to talk by day and produce plutonium at night makes a sham of the negotiations, and only provides diplomatic cover to North Korea’s even increasing nuclear capabilities.

Former Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia James Kelly recently told a Japanese audience that getting North Korea into the room is the just the first step of what is sure to be a long, difficult process. He is right, in part, because North Korea has done a better political job than Washington in the region and U.S. policy has created in Northeast Asia and elsewhere has created a credibility gap that must be overcome if efforts to end North Korea’s program, diplomatically or otherwise are to be successful. As long as Pyongyang can assume the role of victim, U.S. efforts to end its nuclear program have little chance of success. Washington is right to press North Korea to respond to a proposal made last June to end the North Korean nuclear program, but it must lay out in detail what security, political and even economic benefits will come from a decision by North Korea to fully eliminate its nuclear program. Only then can Washington effectively test North Korea’s intentions and rebuild support for its policies in the region. Washington may have a rare, second chance to make North Korea an offer it cannot refuse. This time the U.S. has to get it right.

About the Author

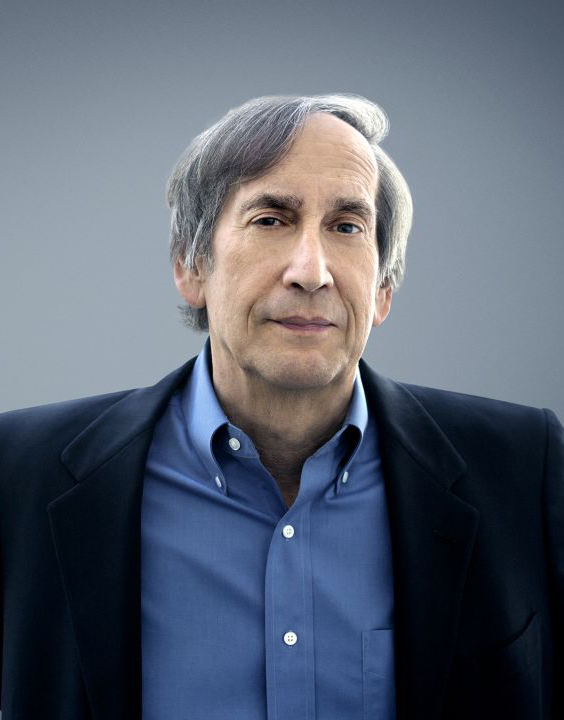

Former Nonresident Scholar, Nuclear Policy Program

Jon Wolfsthal was a nonresident scholar with the Nuclear Policy Program.

- Universal Compliance: A Strategy for Nuclear Security<br>With 2007 Report Card on ProgressReport

- 10 Plus 10 Doesn’t Add UpArticle

Jon Wolfsthal

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Promoting Responsible Nuclear Energy Conduct: An Agenda for International CooperationArticle

These principles aim to codify core responsible practices and establish a common universal platform of high-level guidelines necessary to build trust that a nuclear energy resurgence can deliver its intended benefits.

Ariel (Eli) Levite, Toby Dalton

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

Putin is stalling, waiting for a breakthrough on the front lines or a grand bargain in which Trump will give him something more than Ukraine in exchange for concessions on Ukraine. And if that doesn’t happen, the conflict could be expanded beyond Ukraine.

Alexander Baunov