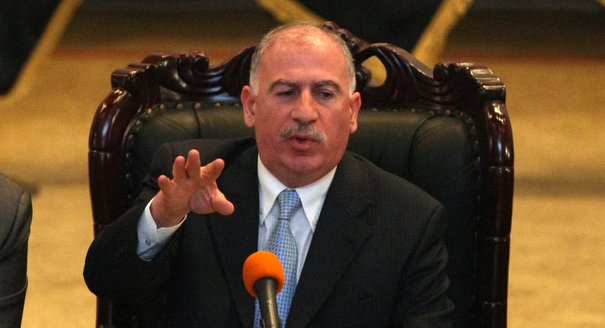

On November 11, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, Kurdistan President Massoud Barzani, and former prime minister and head of the Iraqiya coalition Iyad Allawi signed an agreement to pave the way for the formation of a government in Iraq that includes all major parties and gives representation to all major confessional and ethnic groups. The Council of Representatives, Iraq’s parliament, promptly met and, in rapid succession, elected its speaker, Osama al-Nujeifi, his two deputies, and the president. President Talabani immediately asked Maliki to form the new government, though unofficially.

But two thirds of the parliamentary delegation of Iraqiya, the alliance that received the overwhelming majority of Sunni votes in the March elections, walked out before the president was elected, claiming the November 11 compromise was already being violated. While the Iraqiya delegation returned two days later, Allawi did not, declaring that the agreement was dead. Whether or not he can be persuaded to return, it is a strong warning that the agreement is at best extremely fragile and that the possibility it will fail high.

The details of the November 11 agreement

The implementation of the agreement hinges on two main conditions: first, the creation of a National Council for Higher Strategic Policies which should have real executive power rather than simply being an advisory body; and second, the lifting of the ban on the political participation of three important Iraqiya leaders—Rasem al-Awadi, Saleh al-Mutlaq, and Dhafer al-Aani. During the election campaign the three were accused by the Justice and Accountability Commission of being members of the Ba’ath Party and were prevented from participating in the elections; as a result, they cannot be given posts in the new government unless the decision is rescinded. In addition, the agreement also calls for the launching of a process of reconciliation through the National Council for Higher Strategic Policies.

Several aspects of the agreement are worth noting. First, it reaffirms the confessional character of the Iraqi political system. While the constitution simply provides the outline of a normal parliamentary democratic system, in practice there is now an understanding that government positions have to be apportioned among all major population groups. But the agreement goes one step beyond, de facto establishing which confessional group is entitled to control which position. In the new government, as in the old one, Shi’i control the post of prime minister, Kurds get the presidency, and Sunnis the post of speaker of the Council of Representatives.

The three positions are not equal. The prime minister is the most powerful figure in the government. The presidency is essentially ceremonial, but nevertheless perceived in Iraq as the second most important position—as Kurdistan President Massoud Barzani declared in explaining why the Kurds’ refused to surrender the presidency to Allawi, the president may not have much power but has prestige and moral authority. Foreign analysts argue that the speaker could be a more important player if the parliament played a strong independent role, but there is considerable doubt that parliament will do so. Certainly Iraqi politicians fighting over the spoils did not appear to believe this will be the case. In fact, to bring Iraqiya and the Sunnis into the governing coalition, the National Council for Higher Strategic Policies had to be created and put under Allawi’s control.

Enforcing the agreement?

Second, the agreement does not really appear to be legally enforceable. Its implementation depends on the good will of all major political factions, but particularly that of Maliki. And the provisions can only be implemented quickly by taking some liberties with the constitution and the law. This is particularly true regarding the National Council for Higher Strategic Policies. There is no written agreement about the powers of the National Council, although the verbal agreement apparently indicates that the Council will not simply be an advisory body. When the idea of creating a National Council was first raised by the United States, it was seen by Maliki’s opponents, and even by some of his supporters who worried that he was becoming too powerful, as a way of curbing his power. But Maliki compared it to the U.S. National Security Council, a body that advises the president but has no autonomous power of its own. The differences over its authority remain and even a law will not solve the problem. No matter what the law says, the Council cannot reduce the powers of the prime minister without a constitutional amendment and the constitution precludes amendments until the end of the second election cycle four years hence. Therefore the power of the National Council will depend on Maliki’s willingness to comply with its decisions. The likelihood he will is not great.

The problem of reversing the de-ba’thification decision against al-Mutlaq, al-Awadi and al-Aani is also complex and is likely to entail either a process that takes too long to satisfy immediate political needs or one that overlooks legal niceties. The Justice and Accountability Commission that decides on de-ba'thification is undoubtedly a highly political and partisan body; indeed some Iraqis believe that it acted unconstitutionally when it banned many candidates from taking part in the elections.

Technically, though, its decisions can only be reversed by the courts—at least this is what happened during the election campaign—and the courts would have to review all decisions, not just those against three individuals. But the agreement requires the Council of Representatives to reverse a decision by the Commission. Indeed the walk-out by a majority of Iraqiya members during the first parliamentary session took place because Iraqiya feared the parliament intended to ignore the de-ba’thification issue—it was supposed to take action on this issue before electing the president, as required by the verbal agreement. During their second session on November 13, the Council of Representatives voted to form a committee to study the issue.

Maliki’s power is strengthened

Because the agreement cannot easily be translated into legally binding decisions, its implementation is left to the goodwill of politicians and in particular that of Maliki. This is highly problematic because Iraqi politicians are deeply divided, as reflected in the difficult process of government formation, and because Maliki has emerged from the battle in a strong position—probably stronger than before the elections. He has played his political hand with determination, skill, and more than a little disregard for legality. He has managed, in a paradoxical way, to ensure the support of both the United States and Iran and probably for the same reason—he appeared from the beginning the stronger candidate. And he had amassed during his first term a considerable amount of personal power beyond the official powers of his position.

Maliki was ruthless during the election campaign, supporting the decision of the Justice and Accountability Commission to ban a large number of candidates. When his coalition won two votes fewer than Iraqiya, first he delayed the election certification by demanding a vote recount for Baghdad (it left the results unchanged), then by stalling the government formation process until he could secure a winning coalition in the parliament. He never entertained the possibility that somebody else could be charged with the task of forming the government.

In the meantime, he insisted that he was not simply the head of a caretaker government, but a prime minister with full powers—as long as he did not need action by the parliament, he could make any decision. During a visit to Damascus in October, for example, he signed a trade agreement with Syria, rejecting criticism that he had exceeded his prerogatives as caretaker prime minister in doing so. When rival parties, including the majority of Shi’i parties, were refusing to accept him as prime minister for a second term, he repeatedly reminded Iraqis that as prime minister he commanded the armed forces, an accurate but nevertheless threatening statement when made in the context of a domestic political battle. In fact, not only he is commander-in-chief, but the capital’s special unit, the Baghdad Brigade reports directly to him, as do some intelligence agencies. It is thus difficult to believe that Maliki will willingly implement an agreement with the other political parties that would significantly curb his own power.

Maliki was also aided in forming the government by the support he received from both Iran and the United States. Maliki was facing two obstacles in the formation of the government: other Shi’i parties who wanted an alliance with Maliki’s State of Law Coalition but did not want him as prime minister; and Iraqiya’s insistence that, having won two more parliamentary seats than the State of Law Coalition, it had the right to form the government. In the end, it was Iranian pressure that brought the Shi’i parties to accept Maliki as prime minister, first by convincing Moqtada al-Sadr to back him, and then breaking the resistance of the other members of the Iraqi National Alliance—Fadhila, ISCI, and the Badr Brigades. And it was the United Stats that eventually prevailed upon Allawi and Iraqiya to join in a national unity government with Maliki as prime minister.

With the election of the speaker of the Council of Representatives and the president, Iraq’s formal institutions have started functioning again. Maliki is now prime minister-designate. He has 30 days to form a cabinet and present it to the Council of Representatives for approval. The negotiations and bargaining over government posts of the coming weeks will provide some indications whether the agreement announced on November 11 can survive the reality of power politics. If the law setting up the National Council on Higher Strategic Policies is not enacted and the three banned Sunni politicians are not reinstated before the government is formed, the implementation of the agreement is likely dead. Allawi may have simply jumped the gun on a collapse that was bound to happen in any case.