Sergei Aleksashenko, Mikhail Krutikhin, Yuval Weber

Source: Getty

Russia: Unstable Economy and Political Crisis

Russia’s GDP is expected to grow at low rates the next two years and the country's budgetary outlook remains uncertain, while recent riots and violence suggest that the country’s political situation is deteriorating.

Though the rise in oil prices has strengthened Russia’s economy, low growth is still likely this year and next. The budgetary outlook remains uncertain—the government promises to slash spending even as it announces new initiatives—leaving policy makers with a tough choice, particularly as parliamentary and presidential elections approach. Most importantly, however, the country’s political situation appears to be deteriorating, overshadowing all other arenas.

Economic Stagnation

The Ministry of Economic Development (Minecon) predicts that GDP will grow by 3.8 percent this year—slightly below its September forecast (4.2 percent) and significantly below IMF, World Bank, and varios investment bank estimates (4.5-5 percent). But even Minecon’s estimate looks too optimistic for several reasons.

First, 3.8 percent annual growth would require a very strong economic performance this quarter. GDP—which grew by 3.7 percent in the first three quarters of this year—would have to outpace last year’s fourth quarter growth of 7.7 percent (q/q, annualized). Second, the economy has been extremely unstable all year—four of the first ten months showed signs of a recession, according to Minecon. And, though this summer’s drought hurt growth—reducing annual GDP by 0.65 percent—it cannot fully account for the country’s low growth rate. The economy’s loss of momentum and inability to find new drivers of growth is becoming increasingly obvious.

Furthermore, given that last year’s recovery was V-shaped and the gap between annual and fourth quarter GDP levels is therefore larger than usual, 3.8 percent annual growth would translate to only 1.1 percent growth from the last quarter of 2009.

Forecasts for 2011 are not optimistic, either. The government expects GDP to grow by 4.2 percent, driven by investments from state companies (Gazprom, Russian Railways, and the electric power industry), a recovery in inventories, and a higher oil price. However, many political opponents, as well as experts and business leaders, argue that a tax increase—set to begin in January, expected to gross 2 percent of GDP, and concentrated in the labor-consuming sectors—will reduce private investment and perpetuate the current economic structure, in which extraction and raw material exports remain the most attractive sectors.

Furthermore, if carried out, planned budget cuts—which target investments and public demand—will also inhibit growth. The government cut spending by 2 percent of GDP this year and is planning to cut an additional 1.5 percent in 2011. The actual budget outlook is unclear, however, as discussed below.

Finally, policy makers cannot expect an external environment as favorable as this year’s, which included oil price growth of approximately 20 percent. With China’s economy showing more and more signs of overheating, Beijing will likely reduce its external demand for raw materials, thereby lowering the world oil price. On the other hand, if the oil price continues to increase, it will eventually dampen economic recovery in the developed countries.

Thus, the government’s forecast for 2011 is overly optimistic; 2–3 percent growth is more reasonable. If this estimate holds true, the economy will not return to its pre-crisis maximum (2nd quarter 2008) until mid-2013,1 leaving Russia the proud G20 winner of not only deepest economic decline during the crisis, but also of slowest post-crisis recovery.

An Incomplete Budget Picture

According to Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin, the budget deficit will not exceed 4.3 percent of GDP this year—significantly less than the 5.3 percent expected at the beginning of the year. However, these figures don’t tell the whole budget story. Public finances appear to be growing increasingly dependent on oil price increases, and the non-oil deficit—which was 6.5 percent of GDP in 2008—may reach 11.9 percent of GDP this year.

Kudrin’s statement, made to the Auditing Chamber in December, was highly symbolic, as he seeks help in fighting the president’s and government’s attempts to increase public spending next year. The battle will be a hard one, however, as parliamentary elections approach next December. Traditionally, public spending has increased substantially in the run-up to elections, and there is no reason to expect next year to be different.

In fact, the spending increase has already begun. This fall, President Dmitri Medvedev declared that police salary increases—not included in the budget brought to Parliament—would start in 2011, and military spending is set to grow substantially as well—70 percent in 2011–2013, rising from 2.8 percent of GDP in 2010 to 4-4.2 percent of GDP by 2020.2 In addition, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin recently allocated a substantial sum of money to upgrading the military industry.

Furthermore, with inflation likely to exceed the estimate included in the 2011 budget, pensions will almost certainly rise significantly next year. Inflation began to accelerate in the middle of the summer, and the government raised its expectation for annual inflation from no more than 7 percent to more than 8.5 percent this year and up to 8.8 percent next year. As the prices of grains, vegetable oil and butter, sugar, dried milk, and meat rise, inflation could accelerate to more than 10 percent (annualized) by next May.

Assuming oil prices do not change, policy makers will face a tough choice: either accept a higher budget deficit over the next few years and forget about erasing the deficit by 2015, or sharply reduce all other spending, including on education, public health, and infrastructure.

Deep Political Crisis

More than $21 billion—or approximately 5 percent of quarterly GDP—of capital flowed out of Russia from August to November, according to the Bank of Russia, and the current account surplus narrowed significantly, leading the Bank of Russia to sell $13 billion in reserves. The sharp spike in outflows was associated with growing negativity in Russia’s business community, which opposes the coming tax increases but cannot resist the growing corruption or use the legal system to protect its interests. In addition, an informal race between Medvedev and Putin for candidacy in the 2012 presidential campaign has increased political uncertainty.

Until recently, the term “political uncertainty” was hardly applicable to Russia. Many experts predicted that the Putin-Medvedev tandem would stay in power until 2024 or 2036, and though their words occasionally differed, their actions were in sync. Now, however, the first outward competition between the two may be building as Medvedev appears to be seeking another term in office.

Though this competition has not changed Russia’s political structure or institutional framework, several other recent events have demonstrated the degree of Russia’s corruption and degradation, further casting doubt on the ability of Russia’s economy to recover.

First, twelve people were massacred in the small southern town of Kushchevskaya last month. A group of federal TV journalists exposed this event and the larger tragedy: over the last ten years, gangsters have dominated the town’s authorities and security agencies, while receiving reliable protection at the regional level. The situation appears to be so dreadful, and the population so frightened, that even federal investigators have been unable to unearth the full scale of the gang or its connections.3 Since then, similar situations have been exposed in the cities of Volgodonsk and Gus-Khrustalny.

After the massacre, Valery Zorkin, chairman of the Constitutional Court, published an article in the government’s newspaper, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, arguing that the country is in danger of becoming a criminal state. He further asserted that the government—which is incapable of protecting its citizens from the brutal force of bandits and corrupt individuals—is destroying itself. Unfortunately, everything he said is a tragic reality in today’s Russia.

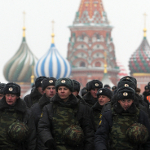

The next day, a crowd of 5,000 people with a nationalist agenda4 seized a central square near the Kremlin. The police were unable to restore public order, and gangs beat people of non-Slavic appearance and smashed buildings in the city’s center. Over the next week, similar, smaller events occurred in Russian cities, with the police detaining hundreds of people.

Though many experts fear that the political system is now so entrenched it is incapable of reform, it is possible—and necessary—to address this political crisis. Today’s political system centers on personal authority, property, and corruption. Any real reform will force those in power to lose their monopoly but—without a war on corruption—the state will soon collapse under its own weight and the country will dissolve, much like the Soviet Union.

Unlike the Soviet Union, however, today’s disintegration may end in the transition of power to criminal groups, rather than to newly formed states. Undoubtedly, this political situation will dominate all else in Russia—at least for the near future.

Sergei Aleksashenko, former deputy minister of finance of the Russian Federation and former deputy governor of the Russian central bank, is a scholar-in-residence in the Carnegie Moscow Center’s Economic Policy Program.

1. If 4 percent growth is achieved in 2011, the economy will return to its pre-crisis maximum one year earlier.

2. Leaders believe that military modernization will support Russia’s high-tech industries.

3. The leader of the gang attended President Medvedev’s May 2008 inauguration as a member of the regional delegation.

4. The unrest in Moscow started with demands for the comprehensive investigation of the murder of a young man. That phase was led by several inhabitants of Dagestan, a republic in the Caucasus, but after bribes were paid, the police removed them. Thus, a request for equal legal treatment devolved into a nationalist demonstration.

About the Author

Former Scholar in Residence, Economic Policy Program, Moscow Center

Aleksashenko, former deputy minister of finance of the Russian Federation and former deputy governor of the Russian central bank, was a scholar-in-residence in the Carnegie Moscow Center’s Economic Policy Program.

- What Should We Do About the Weakening Ruble, Lower Oil Prices, and Sanctions?Commentary

- Is There a Solution?Commentary

Sergei Aleksashenko

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- A China Financial Markets PostCommentary

Description of the post.

Michael Pettis

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Arms supplies from Russia to Iran will not only continue, but could grow significantly if Russia gets the opportunity.

Nikita Smagin

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …