Raluca Csernatoni, Sinan Ülgen

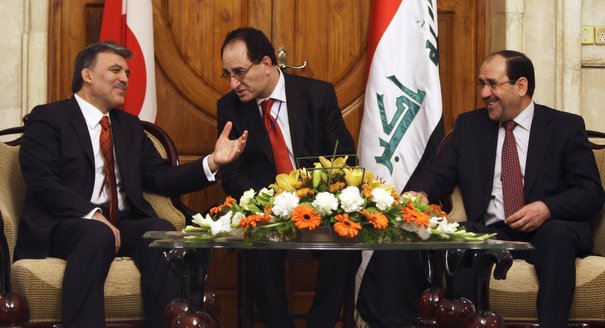

Source: Getty

From Inspiration to Aspiration: Turkey in the New Middle East

The Turkish model of governance can have a significant impact in the Arab world if it is presented in a nuanced, careful way—sector by sector and issue by issue rather than in any wholesale fashion.

With democratic change struggling to take root in the Arab world even after the fall of several autocratic regimes, the question naturally arises whether Turkey can serve as a model for those who hope to usher the region through the difficult transition to a more democratic order.

At first blush, there seem to be significant barriers to applying the Turkish model to the Arab context. For instance, the secularism so cherished by Turks was originally imposed on them using decidedly undemocratic means. Arab leaders who aspire to instill secularism in their countries under conditions of democratic opposition would face a much different challenge. Similarly, Turkey’s Western credentials—its EU candidacy and its membership in NATO and the Council of Europe—do not obviously apply in this situation. And the difficulties that the European Union has faced in developing an effective neighborhood policy for the southern Mediterranean region make clear that these ties are complicated.

There is no straight-line path to operationalizing the Turkish model in the Arab context. There are nonetheless several reasons to take the idea seriously.

To start with, Samuel Huntington pointed out the existence of a “demonstrative” effect, whereby the example of earlier transitions provided models for subsequent efforts at democratization that in turn provided models for other efforts, and so forth. In this sense, the “Turkish model” would apply to the Arab world not so much because of what Turkey does but because of what it is. The second point is the cultural affinity between Turkey and the countries in the region. In essence, the countries of the Middle East and North Africa find Turkey’s own experience more meaningful and see it as more relevant and transposable than the similar experiences of non-Muslim nations. The domestic transformation of Turkey, brought about over the past decade by a ruling party with roots in political Islam, can only enhance the effectiveness of such cultural affinity.

The Turkish model, therefore, can have significant impact in the Arab world if it is presented in a nuanced, careful way—sector by sector and issue by issue rather than in any wholesale fashion. Turkey’s experience can be brought to bear on a number of significant policy areas covering political reform, economic reform, and institution building. In all these areas, Turkey has a valuable role to play in supporting, sustaining, and consolidating democracy and state-building in the Arab world.

The onset of the Arab Awakening presents the world with an historic opportunity to launch the third great wave of transatlantic collaboration (following the reconstruction of Europe after 1945 and the re-integration of Eastern Europe after 1989). The distinguishing feature of this third wave will likely be Turkey’s active involvement, after playing only minor supporting roles in the first two waves.

Turkey’s role as a model for budding democracies also offers the country an opportunity to revitalize its partnership with the West. What better way to allay concerns over Turkey’s increasing foreign policy unilateralism than to induce Turkey to use existing multilateral platforms in a grand program of transformation throughout the Arab world? A Turkey acting in unison with the West to foster democracy and the rule of law in the Arab world would certainly provide the ultimate proof that the Turkish model is not only relevant to policy in the region but a lasting success story.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Europe

Sinan Ülgen is a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, where his research focuses on Turkish foreign policy, transatlantic relations, international trade, economic security, and digital policy.

- Can the EU Achieve Its Tech Ambitions?Q&A

- Can the EU Overcome Divisions on Defense?Q&A

Catherine Hoeffler, Sinan Ülgen

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- Axis of Resistance or Suicide?Commentary

As Iran defends its interests in the region and its regime’s survival, it may push Hezbollah into the abyss.

Michael Young

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Arms supplies from Russia to Iran will not only continue, but could grow significantly if Russia gets the opportunity.

Nikita Smagin