Frederic Grare

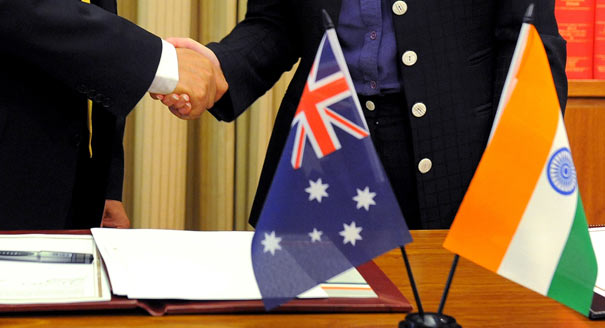

Source: Getty

The India-Australia Strategic Relationship: Defining Realistic Expectations

Mutual indifference has long characterized relations between India and Australia, but the two countries’ interests are increasingly converging.

Mutual indifference has long characterized relations between India and Australia, but the two countries’ interests are increasingly converging. In particular, New Delhi and Canberra are both wary of China’s growing assertiveness in the Asia-Pacific region. Yet there are several constraints hindering the development of a strong India-Australia partnership, and both countries need to be realistic about the prospects for a closer strategic relationship.

Key Themes

- Trade between India and Australia has increased in recent years, as have the countries’ shared strategic interests in the Indian Ocean region.

- China’s rise concerns New Delhi and Canberra, but for different reasons. New Delhi is anxious about persistent territorial disputes with Beijing and China’s increased military presence in the Indian Ocean. Canberra fears being caught in a confrontation between Beijing, its closest economic partner, and Washington, its closest security ally.

- India and Australia do not want to antagonize China, especially given Beijing’s superior military capabilities, but they want to prevent the emergence of a China-dominated regional order.

- Neither country views the other as a potential security provider in the face of China’s rise, yet Australia hopes India will play a leading role in building a new regional order that is not dominated by China.

- India is preoccupied with domestic economic and security concerns, and it must walk a fine line in building partnerships that hedge against China without compromising its own strategic autonomy. Because both India and Australia enjoy strong ties to Washington, they have few incentives to look for alternative partnerships.

- India-Australia cooperation in multilateral organizations is likely to remain limited to low-level regional security issues, such as piracy, for some time.

Implications for the Future of the Relationship

Shared concerns do not necessarily mean a common approach. India and Australia’s overlapping interests and mutual concern about China will not provide a sufficient unifying force to form the basis of a stronger strategic partnership.Strategic and security cooperation is likely to remain limited. Significant collaboration in the larger Indo-Pacific region will be difficult to achieve. It will require increasing the military capacities of both countries and building mutual trust.

Low-level technical cooperation can build confidence and capacity. India and Australia are likely to deepen cooperation on nontraditional security issues where their interests overlap, such as maritime security in the Indian Ocean. Such cooperation will strengthen the relationship and lay the foundation for future joint efforts to tackle larger strategic issues.

The relationship will not change overnight. Patience and realistic expectations are central to the construction of a deep India-Australia strategic partnership.

Introduction

India and Australia, the largest maritime powers among the littoral states of the Indian Ocean, constitute the region’s geopolitical poles. This position gives them particular responsibility for the security of the region, and it means that the future of the India-Australia strategic relationship could affect far more than just New Delhi and Canberra.

Relations between India and Australia have long been characterized by mutual indifference, in part because neither country is central to the security of the other. For decades, they operated in separate strategic spheres.

But that situation may be changing as their strategic interests are becoming more and more convergent. Trade between the two countries is growing—and, along with it, shared strategic interests. Given both countries’ increasing power projection capacities and the increasing importance of the Indian Ocean region to their strategic calculations, their spheres of action and influence are beginning to overlap, making an enhanced dialogue necessary.

Moreover, the two countries’ perceptions of their strategic landscapes—especially regarding the role of China—align more closely than ever before. India and Australia increasingly share a common apprehension about China’s rise, although for different reasons. India’s border dispute with China remains unresolved, and China’s growing military capabilities, as well as its increased presence in the Indian Ocean, are a source of anxiety for New Delhi.

Canberra fears that it will one day be forced to choose between its long-standing security alliance with the United States and its economic well-being, which depends in large part on maintaining solid trade relations with China.

For Canberra, the new Chinese capabilities introduce a disconnect between Australia’s economic and strategic partnerships. Canberra fears that it will one day be forced to choose between its long-standing security alliance with the United States and its economic well-being, which depends in large part on maintaining solid trade relations with China.

Shared concerns about China may have already affected the political dimension of the India-Australia relationship. The two countries’ relative military weakness vis-à-vis China could have reinforced their political cooperation in Asia-Pacific regional forums, including the East Asia Summit, an annual meeting of regional leaders, and bodies of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus. These organizations represent the closest thing to a regional security architecture. Yet India’s perceived passivity in these forums raises questions regarding New Delhi’s capacity or willingness to play its political role to its full extent.

Despite the increase in the two nations’ common concerns, the development of their strategic relationship remains slow. Paradoxically, the fact that India and Australia share a common, or at least convergent, perception of China as a threat is in fact a disincentive for their operational cooperation. Both countries want to prevent the emergence of a China-dominated regional order. But New Delhi and Canberra are also concerned with not antagonizing Beijing. As a result, their shared China concern will not necessarily translate into a common strategic framework.

The still-limited level of engagement between India and Australia in the strategic sphere also reflects a deeper structural difficulty. As David Brewster, an Australian defense analyst, put it, “the relationship is unlikely to be substantially defined by any perceived China threat.”1 Both states see a number of disadvantages and few benefits in looking confrontational when it comes to China. India does not yet view Australia as a potential security provider vis-à-vis China, while Canberra is trying to avoid being placed in a situation that would imply stark choices between Beijing and New Delhi.

The role of the United States, which is evolving in the context of the U.S. rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific region, also factors into the strategic calculations of Australia and India. Both states see the United States as an invaluable balancer of China’s overall power, especially in the military domain, and pursue closer relations with Washington. However, they perceive some risk in being seen, especially by China, as being too entwined with the United States. In addition, Canberra and New Delhi realize that they cannot decisively influence the policies of U.S. administrations, whose character can vary unpredictably. They therefore want to benefit from U.S. power and policy when Washington acts in harmony with their own perceptions and interests but retain their autonomy when the United States acts in less welcome ways.

Canberra and New Delhi want to benefit from U.S. power and policy when Washington acts in harmony with their own perceptions and interests but retain their autonomy when the United States acts in less welcome ways.

In theory, the fact that India and the United States have undergone a rapprochement since the turn of the century should make it easier for New Delhi to improve its relations with Canberra. All three states could be strategic partners. Yet in practice, the maturing partnership between India and the United States constrains the development of security relations between India and Australia. Because both New Delhi and Australia enjoy strategic ties to Washington, they have fewer incentives to look for alternative partnerships. As a result, India and Australia may hold convergent interests, but they feel no need to deviate from their current parallel trajectories with the United States to pursue them.

All this means that the India-Australia strategic and security relationship is likely to remain limited in the foreseeable future. The obstacles to closer strategic cooperation seem insurmountable, at least for the time being.

Shifts in the India-Australia Relationship

For much of their histories, Australia and India have had divergent strategic trajectories, and their different commercial goals and strategies prevented the development of closer relations between the two countries. During the Cold War, their relationship was characterized by what Brewster calls “divergent geopolitical perspectives, ideological differences and weak economic links.”2

Australia always believed its security to be best insured by a close alliance with the United States, and it maintained a commitment to regionalism and multilateral dialogues that did not include India.3 New Delhi, by contrast, was the leading advocate of nonalignment and jealously preserved its strategic autonomy.

But the end of the Cold War and India’s decision to restructure its economy in 1991 produced what Meg Gurry of the Australia India Institute in Melbourne calls a “radically different strategic and commercial climate, one which is obviously far more conducive to the development of closer ties than in the past.”4 As a result, relations between Australia and India began intensifying even before the emergence of China as a strategic concern for both countries. Australia’s exports to India grew substantially in the first half of the 1990s, from about $530 million in 1989–1990 to $881 million in 1994–1995.5

This economic cooperation has continued to deepen since the turn of the century, with Australians increasingly seeing India as a rising global economic player and a potential export destination. Trade grew by 24.6 percent per year between 2000 and 2009,6 making India Australia’s tenth-largest two-way trading partner and fifth-largest export market. Moreover, India is currently Australia’s seventeenth-largest foreign investor, while Australia is the 22nd-largest investor in India.7

These increasing economic ties have helped convince Canberra to improve its relationship with New Delhi. In September 2013, the Australian government released a country strategy for India as part of a series of similar documents outlining a strategy to develop relations with countries identified as priorities “because of their size, economic links with Australia and strategic and political influence in the region and globally.”8 The document was not simply the product of some specialized government agency. It reflected the views of Australian states and territorial governments, business representatives, academics, and community stakeholders. As such, it enumerated as objectives a number of ways to link these diverse categories of actors. This document, reinforced by official Australian statements, indicates an evolution in India-Australia relations.

The security relationship between the two countries has gained momentum alongside the economic one, with Australia making considerable efforts to develop a comprehensive strategic relationship with India. This shift has not been without difficulties—Canberra doubts India’s capacity to overcome the challenges it faces at home and in its immediate neighborhood, let alone its capacity to achieve great-power status—but Australia has come to look at India as a potential partner.9

According to a task force on Indian Ocean security at the Australia India Institute, Australia recognizes its “shared interests with India in promoting regional security and stability.”10 With the rise of China and the uncertainties regarding what the U.S. posture in the Indo-Pacific will be in the context of Washington’s rebalance toward the region, the two countries can no longer ignore each other. Australia acknowledges India’s growing military capabilities, although it does not fear the emergence of a hegemonic India in the Indian Ocean. Instead, it expects India to play a greater role in the management of maritime security in the region.

Since 2008, all major initiatives to give substance to the bilateral relationship have come from Australia. Canberra first moved to expand high-level defense dialogue and then to transition from dialogue to practical cooperation, with a particular emphasis on maritime security in the Indian Ocean. In 2009, an Australian defense white paper stated that “as India extends its reach and influence into areas of shared strategic interest, . . . [Australia] will need to strengthen . . . [its] defence relationship and . . . [its] understanding of Indian strategic thinking.”11

Later that year, a joint security declaration, signed by the two countries, identified eight potential areas for cooperation: defense dialogue, information exchange and policy coordination in regional affairs, bilateral cooperation in multilateral forums, counterterrorism, transnational organized crime, disaster management, maritime and aviation security, and law enforcement cooperation. The document advised achieving this cooperation through a variety of mechanisms such as the exchange of high-level visits, including by foreign ministers; defense cooperation, including policy talks at the level of senior officials; staff talks; service-to-service military exchanges and participation in exercises; consultations between both countries’ national security advisers; bilateral consultations to promote counterterrorism; and knowledge and experience sharing on disaster prevention and preparedness as well as relevant capacity building.12

In conjunction with the joint declaration, India and Australia also concluded cooperation arrangements in matters of intelligence sharing, border security, terrorist financing, money laundering, and law enforcement. However, they achieved remarkably little in matters related to hard conventional security.

The declaration’s main merit was to establish a framework for the further development of the security relationship. But, because it complemented other bilateral security arrangements between Australia, the United States, and Japan, Brewster points out that it has been interpreted in some quarters as “heralding a coalition among Asia-Pacific maritime powers implicitly aimed at containing China.”13 He argues that the declaration can certainly be seen as an implicit message to China about the potential for enhanced cooperation among the Asia-Pacific region’s maritime democracies but that the network of security relationships among Japan, India, Australia, and the United States does not amount to any sort of coalition.14

In 2013, an Australian Ministry of Defense white paper underlined once again that Australia and India have a “shared interest in helping address the strategic changes that are occurring in the region.”15 In June 2013, Indian Defense Minister A. K. Antony made the first-ever visit of an Indian defense chief to Canberra. The visit was a powerful symbol of closer ties between the two countries, and Antony and his Australian counterpart, Stephen Smith, issued a statement officially reiterating their commitment to the 2009 joint security declaration.16

Nonetheless, cooperation between the two countries remains largely restricted to soft security and dialogues.17 India did provide a ship for the International Fleet Review, a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Australian navy’s first entrance into Sydney Harbor that includes a ceremony, conducted in Sydney in October 2013, and a joint naval exercise, scheduled for 2015. Still, operational coordination between the two militaries remains weak. Both sides are very cautious about giving the relationship a strategic significance that could be interpreted as even the beginning of a coalition against China.

Evolving Strategic Postures Amid a Shifting Balance of Power

India and Australia are now faced with a strategic development they cannot ignore—the rise of Asia and, more specifically, China. Yet New Delhi and Canberra have reacted differently to this fundamental shift in the balance of power both in Asia and around the world. To understand the difference between the strategic perspectives of Australia and India regarding the rise of China, it is necessary to understand the impact of the rise of Asia as a whole on the two countries.

Australia’s View of Asia’s Rise

Seen from Canberra, the rise of Asia is neither a new nor an unwelcome phenomenon. Australia’s prosperity has always been intrinsically linked to that of the region, so Asia’s ascent has made for a more prosperous Australia since long before the slogan of a “rising Asia” became fashionable. As Michael Wesley, professor of national security at the Australian National University, observes, “Japan, along with Korea, Taiwan, China and the countries of South-east Asia, has accounted for two thirds of Australia’s trade for a quarter of a century.”18 Until recently, China’s economic growth only added to Australia’s prosperity.

This economic trend is likely to continue in the next few decades, and the Australian government sees itself in a good position “to make the most of the opportunities that will flow from the Asian century.”19 But its strategic outlook will change.

Australia’s economic ties in Asia have furthered its strategic objectives because, according to analysts at the Australia India Institute, “for most of its history as an independent country, Australia has had the luxury of having its key economic partnerships aligned with its key security partnerships.”20Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia were all part of a Western-dominated system of security alliances that included Australia.

China’s emergence as a global actor could challenge the U.S.-dominated global and regional order in which Australia has functioned since independence.

Now, China is Australia’s top trading partner, a fact that decouples Canberra’s key economic and security partnerships. This situation is not unique to Australia. It is shared by a number of countries, including the United States. But Australia is a junior partner in the alliance with the United States and would therefore see its own diplomatic margins vis-à-vis China disappear should the relationship between Washington and Beijing deteriorate.

Relatedly, China’s emergence as a global actor could challenge the U.S.-dominated global and regional order in which Australia has functioned since independence. This reality suggests a possibility of political, economic, or even military coercion by China should Canberra take stands that Beijing considers inimical or hostile.

There a number of scenarios that could potentially lead to a situation in which Canberra would be forced to choose between Washington and Beijing. A conflict between China and the United States over Taiwan, for example, could require Australia to pick a side. This happened in 1996, when Canberra supported a U.S. aircraft carrier deployment around Taiwan, prompting Beijing to freeze all ministerial contacts with Australia. The territorial dispute between Japan and China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands could also become an open conflict that would force Canberra to take a position on the legal and territorial issues involved in the East China Sea for fear of failing its alliances. The probability of such scenarios is low, but their possibility is real, and Australia’s decisionmakers have to integrate these prospects into their strategic calculations.

From that perspective, what matters to Australia is less the power shift from the West to Asia and more the power shift within Asia. Hence, Canberra feels compelled to look for partners, in particular in the Indian Ocean, to ensure the security and openness of the region’s sea lines of communication. Similarly, it needs partners to help shape a regional order in which middle powers like itself are not marginalized. Australia’s 2012 foreign policy white paper thus lists a series of actions aimed at deepening and broadening its relationships in Asia, with a high level of priority given to its relations with ASEAN as well as with individual countries, such as China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and South Korea, with which it intends to establish or extend comprehensive bilateral architectures.21

India’s Perspective on the Asian Century

India, like Australia, has been a net beneficiary of Asia’s rise since the early 1990s, and New Delhi shares Canberra’s primary concern with the shift of power within Asia as opposed to on a more global scale. Also like Australia, India is looking for ways to fashion a multilateral security order in the Indo-Pacific and is now committed to an open economic order. But the two countries arrived at these similar positions in very different ways.

India’s starting point differs fundamentally from Australia’s. Although Indian scholars and diplomats like to reflect on India’s deep historic ties with and cultural influence in Asia, the country found itself regionally isolated at the end of the Cold War. India’s drift toward the Soviet Union, despite its proclaimed nonalignment, had gradually alienated it from the non-Communist Asian nations, while a 1962 war with China had de facto cut New Delhi off from most Communist countries in the region.

After the Cold War, India had to regain its status as a player on the Asian scene. Economic necessities and a shared wariness of a potentially hegemonic China created a convergence of interests that underpinned India’s renewed engagement with Asia, an approach initiated and termed the “Look East” policy by Prime Minister Pamulaparti Venkata Narasimha Rao in the early 1990s. While the Look East policy was motivated primarily by economic considerations—in particular the need to attract foreign investment and develop trade—it was also the product of strategic and political considerations. Rao recognized the need for India to reintegrate itself within Asia’s strategic and political institutions and led New Delhi to seek greater cooperation first with Southeast Asia and later with East Asia and the rest of the Pacific Rim.

The power shift resulting from the de facto dominance of China in Asia, together with other factors, has not fundamentally changed India’s attitude toward regional partnerships. Indian strategic thinkers make this clear in Nonalignment 2.0: A Foreign and Strategic Policy for India in the 21st Century, a report by a group of Indian analysts supported by officials in the Indian government that is the closest thing the country has ever produced to a grand strategy document.

The report explains New Delhi’s reluctance to enter into an alliance with Washington, contending that although India clearly understands its strategic convergence with the United States, it fears that it could become the victim of either a zero-sum conflict between Beijing and Washington or a too-close relationship between these two giants.22 The first option would force New Delhi to choose between China and the United States and would most likely expose it to Beijing’s wrath, while the second would deprive it of any support in case of a major crisis with China.

India also has a long-standing concern with maintaining its strategic autonomy, a consideration that has made it reluctant to embrace closer ties to the United States. New Delhi has sought to preserve and expand its own freedom of action—unlike Australia, which has always been a member of the Western system of alliances. As a result, India has been careful to avoid being seen as pro-Western or to fuel suspicions in Beijing that it was maneuvering against China. Both considerations also prevented New Delhi from embracing closer ties with ASEAN.23

Post–Cold War developments have, however, led to an evolution of the meaning of strategic autonomy for India. The Look East policy offers the country a way to maintain its cherished autonomy through regional cooperation. This strategy is designed to allow India to leverage the forces of partner countries in situations of strategic convergence by establishing close ties that enhance conventional deterrence, all while maintaining its ultimate autonomy of decision. In practice, the policy allows India to benefit from political support in Asia without ever committing to any type of relationship that would tie the hands of its diplomacy and force it to make choices that Beijing would consider hostile.

As a result, Indian strategists constantly reaffirm ASEAN’s role as the linchpin in their perception of Asia and its future. They also look to the association as an essential component of the construction of a security order that India would like to be in its own interests and compatible with its own constant (albeit revised) search for strategic autonomy. Then foreign minister Jaswant Singh first articulated this view in a speech in Singapore in June 2000, stating that

India, like some other Asian powers, has tended towards a more independent security paradigm but this approach does not exclude regional cooperation in security matters, in a cooperative framework, as India’s participation in the ASEAN Regional Forum demonstrates. We see in the . . . [forum] an experiment for fashioning new, pluralistic, cooperative security order, in tune with the diversity of the Asia-Pacific region, and in consonance with transition from a world characterised by balance of power and competing military alliances. Though the . . . [ASEAN Regional Forum] covers a broader region, we believe that its nucleus is ASEAN, that is why . . . [the forum] should be ASEAN driven. Our participation in the . . . [ASEAN Regional Forum] reflects India’s increasing engagement, both in politico-security and economic spheres contributing to the building of greater trust, confidence and stability in the region.24

Competing Visions of a New Asia

There are also nuanced differences between Australia’s and India’s visions for the balance of power in the future Asia. There is no single Australian view on the topic. As described by the Australian National University’s Wesley, Australian perceptions of the future of Asia range from a European-style nineteenth-century concert of powers to a more classically Asian “hierarchy of tributes and forbearance centered on the Middle Kingdom” to a Cold War¬¬–style U.S.-Chinese confrontation. Wesley himself argues that the growing dependence of the major Asian powers on the global economy, and its resulting power dynamic, will prevent any possibility to play power games as doing so would threaten the base of these nations’ stability and prosperity.25

Indian perceptions are not fundamentally different but are somewhat more confused. Indian analysts predict the advent of an Asian concert of powers, of which India would be an integral part. At the same time, they fear the supremacy of the Middle Kingdom but do not actively work to avoid it by trying to create the sort of power dynamics that would prevent power games in Asia.

The discrepancy between Australian and Indian perceptions of the ongoing dynamics in Asia gives rise to an asymmetry in the way the two countries are trying to build their strategic cooperation. Each is too realistic to expect from the other more than it is capable of delivering in the military domain, but Australia is clearly frustrated by what it sees as India’s insufficient commitment and hesitancy in the construction of the regional security architecture.

Security Concerns and the Ambiguous Chinese Factor

To many, such as Sally Percival Wood of Australia’s Deakin University, it seems inevitable that “Australia-India engagement will only deepen as China continues to rise.”26 The contentious character of China’s relations with its neighbors over the past few years certainly explains the newfound desire of both India and Australia to forge a closer security relationship. Yet, common concerns do not necessarily imply similar interests. Nor do these concerns inevitably translate into identical approaches and policies.

While Australia and India share many apprehensions about China, their respective geographies and histories have produced divergent approaches to managing these concerns. China presents Australia with a novel and relatively distant threat, while India sees Beijing’s assertiveness as part of a pressing and long-standing challenge.

But when it comes to a rising China’s role in Southeast Asia, Australian and Indian security interests clearly overlap. Australia fears Chinese pressure on its neighbors, and India does not want Beijing to develop deep influence in the region. Australia keeps publicly proclaiming that India can be a force for regional stability, and New Delhi says the same about Canberra.27 Yet, despite their strategic convergence, their cooperation remains limited.

Australian Concerns About China’s Rise

Economically, China’s rise benefits Canberra because Australia’s current prosperity is based on its exports of commodities. Canberra is thus highly dependent on the positive side effects of China’s growth, such as market stability in Asia; the security of sea lines of communication; and the persistence of a stable, peaceful, and rules-based global order.28

But these economic benefits do little to mitigate Australia’s fears about the potential strategic implications of a stronger Chinese military. These concerns may be somewhat less immediate for Canberra than other regional countries, as Australia’s geography provides it with what Rory Medcalf of the Lowy Institute for International Policy calls “a large maritime barrier against any regional adversary.”29 Yet despite this natural buffer, Australia suffers from a strong sense of insecurity that has historical roots in its limited population relative to its territorial size, exposure to great-power rivalry, and experience with Japanese aggression during World War II. This insecurity is only heightened by the occasional instability of its neighbors.

As a result, Australia perceives China’s military modernization as a potential threat on several levels. First, Canberra sees the growth in Chinese military capabilities as posing a risk—if not a direct threat—of China exerting political and economic pressure on Australia to force Canberra to adopt positions that align with Beijing’s. This would jeopardize Australia’s security interests in the global commons should the two countries diverge at some point.

Second, China’s military modernization introduces potentially harmful instability to Australian interests on China’s periphery. Australian security analysts observe with great care all Chinese intentions and behavior in the South and East China Seas, be it Beijing’s territorial claims, the movement of Chinese forces, or the expansion of China’s air defense identification zone into disputed territory in the East China Sea, a move that drew international criticism.

Third, the surge in Chinese military capabilities raises the specter of a direct military conflict between China and the United States in which Australia would have to choose between its economic and security interests—a disastrous prospect for Canberra whatever the outcome of the conflict.

These perceived threats make Australia wary of a future confrontation with Beijing. According to Australian analyst Daryl Morini, with regard to China,

Australian strategists are no longer asking whether large-scale regional conflict is likely in the coming decades, they are debating how Australia should prepare for war and under which conditions the country should join the fray. . . . Australian strategists and even some politicians are no longer debating the nature of China’s rise, or what it means for Australia—they are calling for rapid investment in submarine capabilities, anti-submarine warfare capabilities, and debating the merit of acquiring a fleet of F-35 fighter planes based on the assumption that “Australia would only ever go to war with China by America’s side.”30

Indian Perceptions of the Chinese Threat

For India, conflict with China is more than just a possibility—it is also a painful memory. China defeated India in the 1962 war, a fact that has for decades had a dramatic impact on New Delhi’s foreign policy, rendering it almost entirely reactive.

Today, China is again India’s main security challenge, and it is becoming increasingly worrisome as the power differential between the two nations continues to widen. China and India have a long-standing disagreement on their border demarcation, and incidents regularly occur on the Line of Actual Control.

Three other issues stand out in India-China security relations: Pakistan, Tibet, and the Indian Ocean. China’s support for Pakistan is well-known. Beijing has been a constant source of military backing for Islamabad. China is not alone in providing Pakistan with military hardware, but Beijing’s aid to Pakistan’s missile and nuclear programs has deeply altered the balance of power in South Asia to the detriment of India. While it is uncertain whether China would take up arms on Pakistan’s behalf, Beijing’s actions have helped produce an Indo-Pakistani deadlock that seems as permanent as it is unstable.

Disputes between India and China over Tibet are perhaps more troublesome. Beijing sees New Delhi’s support for the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan community in exile in India as interference in China’s internal affairs in Tibet. The Indian government fears that the succession of the Dalai Lama, an issue that has risen to prominence since his retirement from political duties in 2011, might become a source of very serious tensions with China because young Tibetan radicals might alter the Tibetan government-in-exile’s peaceful policies and take a stronger stance against the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

Although Indian decisionmakers do not believe that China is currently interested in changing the status quo in Tibet, they fear that Beijing might prove more revisionist after it fully completes its military modernization project. The Indian military is concerned by the strengthening of Chinese military capabilities in the Tibetan autonomous region, in particular by the development of airport facilities, roads, and rail infrastructure. India is well aware that its own infrastructure programs along the border lag behind China’s, but New Delhi is confident that, in the near term, its missile-development and conventional-arms-acquisition programs will help it deter any potential Chinese aggression in the region.

In the Indian Ocean, India fears that a conflict begun on land might escalate horizontally at sea. But the most likely trigger for a maritime conflict between the two nations is the security dilemma that would result from a Chinese naval deployment in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal to protect Beijing’s commodity supplies. While India recognizes China’s need and right to sea lines of communication for its commodities trade, New Delhi would perceive such a deployment as a direct threat to its own interests in a region where it retains naval superiority over Beijing.

New Delhi is also wary of what some strategists see as a Chinese attempt to encircle India. The Chinese deployment of nuclear-powered submarines at about 1,200 nautical miles north of the Strait of Malacca generates anxiety in New Delhi, as do various other Chinese efforts to secure basing rights around the Indian Ocean’s littoral. Rightly or wrongly, India interprets these efforts as evidence of China’s eagerness to control the Indian Ocean region in the immediate vicinity of the South China Sea.31

But Indian analysts are not unanimous in their understanding of China’s presence in the Indian Ocean, despite the Indian Navy’s vociferous objections to the infamous alleged “string of pearls,” a term used to describe the extensive network of Chinese military and commercial facilities around India.32 And India’s official position on the issue has evolved markedly. A joint communiqué issued during then Chinese premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to India in December 2010 stated that “the two sides reaffirmed the importance of maritime security, unhindered commerce and freedom of navigation in accordance with relevant universally agreed principles of international law.”33

Indeed, India and China have made a number of official attempts to resolve their lingering security issues. The two countries agreed to launch a maritime security dialogue during an April 2012 meeting between China’s then foreign minister, Yang Jiechi, and his Indian counterpart, then minister of external affairs Somanahalli Mallaiah Krishna, in Moscow.34 Moreover, despite occasional tensions over border issues (for which a working mechanism of consultation and coordination was established in 2012), India and China do have defense cooperation agreements, although the scope of these agreements is limited to exchanges and consultations.

Persistent Mistrust

Australian analysts and decisionmakers alike tend to take a less sinister view of the Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean than their counterparts in India. They interpret China’s moves in the region as the expression of Beijing’s legitimate interests in protecting its maritime lines of communication with the Middle East and Europe, not as an attempt to encircle India.35 They also maintain that India’s naval procurement program creates a new security dilemma in the region and carries what Brewster calls “the potential to fuel confrontation between India and China in the Indian Ocean and even the South China Sea.”36

A fundamental mismatch in the way Canberra and New Delhi perceive the security threats accompanying China’s rise prevents Australia and India’s common concerns from bringing them any closer.

This fundamental mismatch in the way Canberra and New Delhi perceive the security threats accompanying China’s rise prevents Australia and India’s common concerns from bringing them any closer. Neither Australia nor India seeks to exclude China from the security order. But according to some Australian analysts, there is a persistent “mutual misperception” among Australia and India regarding Canberra’s China policy.37

India believes that Australia faces a permanent temptation to accommodate China. New Delhi sympathizes with this temptation to some extent—neither India nor Australia wants to be caught in the middle of a crisis in the U.S.-China relationship and forced to choose between Washington and Beijing—but it fears that Canberra might concede more than what is necessary to maintain peace. India therefore fears an Australian tilt toward Beijing, a perception reinforced in 2008 by Canberra’s refusal to participate in a quadrilateral dialogue with Washington, Tokyo, and New Delhi.

This perception has strained the already-limited strategic cooperation between Canberra and New Delhi. Since 2007, Australia has not taken part in the annual Malabar naval exercise, an extensive military exercise that began as a bilateral U.S.-India affair and has expanded to occasionally include Australia, Japan, and Singapore. In 2008, New Delhi declined Canberra’s invitation to join Australia’s principle multilateral naval exercise, the Kakadu.38

The Effects of the U.S. Rebalance

In some ways, Washington’s rebalance to the Asia-Pacific region may help foster a closer India-Australia alliance. U.S. presence is useful, for example, in managing the asymmetry of expectations between Australia and India when it comes to maintaining regional security. In the short term, the United States provides sufficient security guarantees to allow Australia to wait for India to close the global capability gap with China to a manageable degree.

But even if it does partly compensate for the differences between India and Australia, increased U.S. presence in the region does not eliminate them. Indeed, in many ways the U.S. rebalance may actually prevent India and Australia from developing a closer relationship.

Australia’s Dilemma

Australia’s long-standing alliance with the United States obviates any immediate necessity for a security partnership with India. For Australia, the United States has always been the key security player in Asia. In Canberra, any notion of Washington as a declining strategic power is balanced against the fact that the United States is, and will remain for the foreseeable future, “in a league of its own in global military reach and readiness to use force,” according to a May 2012 address by then Australian high commissioner to India Peter Varghese.39

But Australia’s relationship with the United States is not wholly dependent on Washington. Beijing also factors into U.S.-Australia relations, and the rise of China is creating a serious policy dilemma for Australia. This dilemma is best understood through the writings of Australian professor Hugh White.40 Taking into account the growing strategic rivalry between the United States and China, White argues that although Australia does not face an all-or-nothing choice right now, the current situation—in which “the United States can keep Australians safe while China makes them rich”41—is not sustainable. According to White, Australia will inevitably have to choose between its economic and security interests.

White also argues that the U.S. approach to China is misleading. He notes that while Washington ostensibly “does not ask friends like Australia to choose” between the United States and China, U.S. leaders do press Australia “to do things, such as hosting marines in Darwin, that are clearly intended to counter China’s power, and which they know China will resent.” White concludes that “the idea that . . . [the United States] does not ask countries to choose between Washington and Beijing only makes sense if the United States does not believe that China is challenging American primacy in the region.”42

One does not have to believe that Australia will inevitably face a choice between China and the United States to accept the idea that the necessity for such a choice may one day become a reality. White, for his part, argues that “if Australia wants to avoid decision time, its highest diplomatic priority must be to help stem the escalating rivalry between America and China,” which he contends will only happen if Washington agrees to share power with Beijing.43 Most American analysts, officials, and former officials publically advocate greater U.S. engagement with China. But analysts such as Harvard’s Nicholas Burns argue in favor of “hedging” by maintaining the clear superiority of U.S. and allied military forces “in order to prevent China from becoming the strongest force in the Asia Pacific region.”44 These same experts are also unsure about the U.S. capacity to “retain a preponderance of military power in the region while engaging China successfully at the same time.”45

It makes sense, in this context, for Australia to develop partnerships on China’s periphery. For example, Kishore Mahbubani, Singapore’s former ambassador to the United Nations, argues that “the biggest mistake that Australia could make is to continue on auto-pilot, clinging to Western or American power as its sole source of security.”46

It is unclear whether Australian decisionmakers agree entirely with this analysis, but they have reinforced their relationships with Indonesia and Japan (with whom they signed a joint security pact in March 2007) over the past few years. Relations with India fall in the same category of partnerships, even if Australian expectations for the foreseeable future remain limited.

Partnering with India makes sense for Canberra given the nature of the China-India relationship. The geographical proximity, the asymmetry of power between China and India, and their willingness to avoid conflict contribute to framing a different and less confrontational regional environment than the one defined by the U.S.-China relationship. Therefore, developing relations with India would be useful for Australia as it attempts to define its own strategic environment.

India’s Risk of Isolation

While India is less dependent than Australia on the United States in its relationship with China, the U.S. rebalance also has major implications for New Delhi. Paradoxically, the rapprochement that has taken place between India and the United States since 1998 both removed an obstacle to a potential India-Australia partnership and made such an alliance less likely. New Delhi no longer perceives improving its relationship with Canberra as antagonistic to its own international positioning. But at the same time, the growing convergence and strategic partnership between New Delhi and Washington, underlined by growing military cooperation between the two countries, has diminished India’s need for alternative partnerships. This trend, which is further reinforced by New Delhi’s limited defense cooperation with Beijing, also diminishes the risk of confrontation with China.

In addition, New Delhi’s changing relations with Washington have directly affected the state of its relationship with Beijing. As India’s relations with the United States improved at the turn of the century, China began to reach out to New Delhi. The following decade, which saw the conclusion of the U.S.-India civil nuclear agreement, was the nadir of the China-India relationship, with Beijing approaching India very carefully out of fear that New Delhi might fall into Washington’s sphere of influence.

Since 2008, New Delhi has put some distance between itself and Washington in the expectation that doing so would help India secure a border agreement with China. This agreement has not yet materialized. Given that the United States seems to still be hesitating on its own posture vis-à-vis China, the challenge for New Delhi is to be neither too close nor too distant from Washington.

From this perspective, New Delhi seems to see limited value in an Australian partnership. The immediate impact of such a relationship would be to draw India closer to the United States and modify the delicate equilibrium New Delhi is trying to develop in its relations with China.

Capacities Shape Perceptions

While both Canberra and New Delhi are looking to Washington in some degree, the different capacities of these two nations shape their perceptions of and participation in U.S. policies. Thanks to its less developed economy, for example, India is not as well-equipped as Australia to fully participate in whatever foreign policy initiative the United States may launch to try to mitigate the risks of China’s rise in Asia.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is one such initiative. As it is currently being negotiated, the TPP would be a free-trade agreement between Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. Initiated by the United States, it is part of Washington’s rebalance to the Asia-Pacific region. It is expected to shape Asia’s future economic architecture, countering China by pushing for a deeper set of regional economic rules and expectations than Chinese leaders would prefer.47

For India, the TPP could be a way of strengthening both its partnership with the United States and its relations with its neighbors. It has expressed an interest in participating but, unlike Australia, is not part of the ongoing negotiations.

Prospects for Cooperation

Apart from their bilateral economic relations, cooperation between India and Australia is limited but not absent. New Delhi and Canberra cooperate in two very different domains, uranium sales and multilateral regional institutions, both of which reflect Canberra’s recognition of New Delhi as an Asian player.

An End to the Impasse Over Uranium Sales?

Differences over the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—which Australia has signed and India has not—and over exports of Australian uranium to India have long been major issues in the bilateral relationship. With about one-quarter of the world’s uranium and a large share of low-cost reserves, Australia is one of the top three uranium exporters in the world. Purchasing Australian uranium would enable India to diversify its sources of supply and diminish its dependence on any one of them.48

Canberra has acknowledged that India has a good nonproliferation record, and the two countries have relatively similar nuclear disarmament agendas. Yet until recently, Australia refused to export uranium to India. Canberra’s position is shifting, but its evolution on the issue has been slow, a fact that has long fed India’s resentment of Australia.

Australia decided in 2011 to remove its long-standing ban on uranium sales to India after years of hesitation, a move that constitutes one of Canberra’s major initiatives to improve the relationship. The decision removed an important irritant from the bilateral relationship.

The ban was initially implemented due to the many specific stipulations of Australia’s uranium export policy. According to these restrictions, exports must be for civilian purposes only, and recipients of Australian uranium must be signatories of the NPT and have suitable safeguard agreements in place with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In addition, those nations considered to be non-nuclear-weapon states under the NPT must also have an IAEA Additional Protocol in place to enhance the agency’s ability to detect any undeclared nuclear activities, and all recipient countries must have concluded “an additional treaty-level bilateral safeguards agreement with Australia involving undertakings to account for Australian uranium and any nuclear material derived from it.”49 On top of these stipulations, Australia determines its uranium sales based on its geopolitical considerations and diplomatic interests.

India meets these standards only imperfectly. It is unwilling to accede to the NPT because it sees the treaty as a form of nuclear apartheid. Since 2008, however, the U.S.-Indian civil nuclear cooperation agreement has given India an esoteric status similar to that of a recognized nuclear-weapon state. The majority of Indian power reactors are now under IAEA safeguards, and all future reactors will meet this standard as well. Also in 2008, the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), a multinational body that controls the export of nuclear materials, equipment, and technology, created an exception to its guidelines to allow exports to India.50

Australia recognizes India’s nonproliferation credentials (and supported the exception in the NSG), its restrained nuclear posture, and its willingness to join negotiations for a Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty. It justified denying India uranium on the principle that engaging in nuclear trade with New Delhi would reward noncompliance with the global nonproliferation regime and allow India to use its domestic uranium supplies to expand its nuclear arsenal.

Whatever the justification, the U.S.-India nuclear deal and Australia’s support for the NSG exception produced a contradiction in Canberra’s nuclear policy. Australia was put in the awkward position of continuing to refuse to export uranium to India even though it had helped change the rules to let any such sales proceed legally.

Canberra’s initial response to this conundrum was to reexamine its export ban. In August 2007, the conservative government of then Australian prime minister John Howard announced its willingness to negotiate the export of uranium with India, provided strict conditions were met. These included a safeguards agreement between India and the IAEA, India’s signature of an Additional Protocol equivalent, a consensus by the NSG, the conclusion of a U.S.-India civil nuclear deal (then still in negotiations), and satisfactory progress by India in placing its declared nuclear sites under IAEA safeguards.51

This decision, however, was reversed by Australia’s next prime minister, Kevin Rudd, in January 2008 on the grounds that India was not a signatory of the NPT.52 The decision was perceived in New Delhi as a sign of mistrust, even though in reality it had more to do with domestic politics.

In November 2011, another reversal took place when then Australian prime minister Julia Gillard announced that she would support a policy shift to allow Canberra to negotiate the export of uranium to India for civilian use.53 Her proposal was approved by the Labor Party at its national conference on December 4 of that year.

The new conservative government announced that it will not reverse the 2011 decision,54 and New Delhi and Canberra have begun negotiations on the details that will govern their nuclear trade.55 Still, actual uranium sales to India are unlikely to start soon. Canberra will hold India to the same standards as all other countries to which it exports uranium, in particular a strict adherence to IAEA arrangements and strong bilateral measures to assure Australia that its uranium will be used exclusively for peaceful purposes.56 Canberra and New Delhi will have to sign a detailed protocol covering the safe handling and accountability of Australian uranium.

The reasons behind Australia’s decision to lift the ban are the subject of much debate. Economics alone cannot explain it, especially because the potential economic impact of the decision is debatable. According to the Australian Uranium Association, should the ongoing negotiations lead to an agreement, Australia can expect to sell some 2,500 tons of uranium annually to India by 2030, generating about $309 million per year at current prices.57 But uranium exports themselves are a limited industry. Optimistic assessments anticipate a value of 627 million Australian dollars ($560 million) at best by the end of 2014,58 as compared with the nearly 196 billion Australian dollars ($175 billion) anticipated for the fifteen largest Australian commodities by the same date.59

The decision may have been partly triggered by a sense of relative urgency—with the warming of India’s nuclear ties with the United States, France, and Canada, Australia may have feared being marginalized in India’s diplomatic agenda. A recent country strategy document for India published by the Australian government expressed this concern, saying that Australia “must be mindful of competing demands. The relatively small Indian bureaucracy is actively courted by a large number of international partners.” The document went on to stress that New Delhi is “focused mostly on tackling domestic poverty and ensuring sustainable development” and suggest that Canberra target its approach to those matters in order to get India’s attention.60

There is some evidence that diplomatic imperatives played a central role in Australia’s decision to remove the ban. This is hardly without precedent. Canberra has long sold uranium to Russia and China, neither of which has a particularly neat proliferation record. In both cases, the decision to sell uranium was made to strengthen the bilateral relationship. Prime Minister Howard’s 2007 choice to sell uranium to Russia in order to give substance to the Australia-Russia relationship was part of a larger partnership. A 2006 decision to engage in uranium trade with China also had diplomatic motivations. According to Medcalf, the analyst from the Lowy Institute, the Australian government took into account Chinese needs for nuclear energy “to help fuel its economic development, which in turn would aid social stability within China and reinforce China’s reliability as a destination for other, more lucrative, Australian exports.”61

Similar, if not identical, considerations seem to have prevailed in Australia’s decision to sell uranium to India. The need to get closer to India at a time of power shifts in the Indo-Pacific region may have also influenced Canberra’s choice. Not unlike in the U.S.-India relationship prior to 2008, the nuclear issue still presented a major impediment to any significant rapprochement between the two countries. Then Australian prime minister Gillard made this argument explicitly when she declared in November 2011 that it was time for Australia to “modernize . . .[its] platform” in an attempt to bolster its “connection with dynamic, democratic India.”62 Days later, then foreign minister Rudd echoed this sentiment, remarking that “the strategic relationship with India for the decades ahead is of great importance to . . . [Australia’s] national interest.”63 When the Labor Party made the uranium export policy official, Gillard declared that it was not rational that Australia sold uranium to China but not to India.64

At least symbolically, the nuclear trade deal addressed all these issues and, in India’s mind, constituted an additional concrete step toward ending the perceived nuclear apartheid. New Delhi seems willing to accept Canberra’s conditions for the sale of uranium, but it is still unclear if India will ultimately buy uranium from Australia, as potential suppliers are relatively abundant. Still, the lifting of the ban on uranium sales had the desired effect and has already contributed to the rapprochement between the two countries.

Multilateral Regional Security Institutions

In addition to engaging in nuclear trade, Australia and India could deepen cooperation in the political-security arena, a promising field for the future development of bilateral relations. Many countries in the Indo-Pacific region, including Australia, fear the prospect of an Asian multilateralism dominated by China. There is a consensus among these nations that creating a new framework of multilateralism in the region would help constrain any major-power rivalry. Yet such a framework is so far very limited, although ASEAN has taken the first steps in creating mechanisms for cooperative security in Asia, including the ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asia Summit.

Many countries in the Indo-Pacific are in search of a nonhegemonic regionalism and are looking to India to play a larger role on the regional scene.65 Singapore, in particular, has played a decisive role in helping India become more active in existing regional institutions.

New Delhi has its own reasons for wanting to prevent China from dominating regional multilateral associations. India’s regional aspirations are essentially negative, which means that if it is unable to impose its own leadership on regional security institutions, New Delhi will aim to prevent the dominance of any other power in the region. This is likely to have two practical consequences.

First, it means that India will prefer inclusive arrangements in which all powers participate to exclusive ones. In practice, this means that India will not support any regional institution that excludes China.

Second, it means that India will not help institutionalize any system likely to undermine sovereign decisions.66 New Delhi is likely to favor current institutions such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asia Summit, both of which are essentially talking shops operating by consensus (although India did recently co-chair a working group in the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus, where the constraints on participants are more demanding).

In this, India’s approach is comparable to, or at least compatible with, that of most middle powers in the region, including most ASEAN member states. When choosing which non-ASEAN nations would attend the first East Asia Summit in 2005, ASEAN collectively decided to support an initiative to invite countries outside of East Asia, such as India and Australia, despite Chinese objections. This decision, interpreted by many as ASEAN’s attempt to balance China’s accession to the summit with that of other strong powers, reflected the firm willingness of countries such as Singapore and Indonesia to develop a balanced regional architecture rather than, as C. Raja Mohan has put it, to leave lesser states “to the exclusive embrace of any major power.”67

The East Asia Summit, in addition to advancing India’s needs and supporting New Delhi’s aspiration to a balanced distribution of power in Asia, is compatible with Australia’s participation in the Western alliance system. Australia has always pursued a dual-track order-building strategy in Asia that is centered on its participation in a U.S.-dominated alliance system alongside multilateral regional engagements. The summit thus provides Australia and India with an opportunity to collaborate on regional issues, but they have not used it as a forum for change in the Asia-Pacific region.

India and Australia must play a more active role in institutions helping to build a new regional order. Mere presence in existing security institutions differs from active participation and cooperation.

To truly enhance their role in securing stability for Asia, India and Australia must play a more active role in institutions helping to build a new regional order. Mere presence in existing security institutions differs from active participation and cooperation.

Australian officials, while they publicly praise bilateral cooperation in these institutions, privately lament India’s passivity in regional forums, noting that India has not assumed a decisive role in the construction of a cooperative security arrangement. In part, New Delhi’s passivity is due to the fact that Indian decisionmakers are too aware of their country’s shortcomings to be willing to take the lead on this process. India’s main concern is and will remain in the foreseeable future its own economic development.

There are two organizations in which active cooperation between the two countries does currently take place, both of which are related to the Indian Ocean. This cooperation, however, is limited in scope. An Australia India Institute task force identifies an emerging trend in regional institutions of “parallel tracks separating non-traditional region-based security issues from those of a ‘higher order’ that include but go beyond the region.”68 India and Australia seem to feel comfortable in the first track, where the stakes are much less political. But they are less comfortable in the second track, where they inevitably confront the difficulties posed by their relationships with China.

The first regional organization in which India and Australia cooperate on these first-track issues is the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium. Established in 2008, the symposium is a biennial meeting of navy chiefs. It includes only the littoral states of the Indian Ocean and has a significant security component. Although it is a useful forum for exchanging perspectives on regional maritime security, the weak military capacities of most members limit the symposium’s chances of becoming a meaningful security actor. Indeed, it has so far achieved no concrete objectives.69

More promising is the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA, originally known as the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation), which is likely to become a forum of choice for India-Australia cooperation. Initiated in 1997 by the two countries with the objective of promoting regional trade, the IORA came to include maritime security issues in 2008. These, however, are limited to “small” security matters, such as piracy and illegal fishing, which are important for the Indian Ocean islands but unlikely to make the IORA a major force in regional security.70 For IORA member states, cooperation on these small security matters seems to be more satisfying than attempts to tackle the larger regional issues.

Strategic Perspectives

Despite the compelling reasons for developing a stronger strategic relationship between India and Australia, a deep ambivalence persists on both sides. The vast majority of Australian security analysts support closer engagement with India, but they doubt India’s strategic capabilities and do not think New Delhi should play a large role in any eventual concert of powers in the Asia-Pacific region. Sandy Gordon of the Australian National University probably best sums up Australia’s perception of India: to Canberra, “India is an important emerging power but not yet an important strategic player.”71

Australia sees India as being constrained in a number of ways that prevent it from being the sort of regional and global player that it aspires to be. Canberra notes that large swaths of India’s population live far below the poverty level and that the ambitious growth agenda New Delhi must pursue as a result is likely to divert resources from its power projection abroad. And despite India’s professed eagerness to acquire a force projection capability, the share of defense spending devoted to its blue-water navy has remained relatively constant over the past two decades, increasing only from 13 to 15 percent of the total defense budget.72 Moreover, since the November 16, 2008, terrorist attacks on Mumbai, a substantial part of India’s focus has been on inshore defenses. The imperative to be able to deny an enemy control over large parts of the Indian Ocean—much less to actually control and influence these waters—remains, for India, a distant objective.73

Moreover, most Australian analysts concur that India’s hostile neighborhood condemns it to being essentially a continental power. Canberra sees New Delhi as being tied up in “a tight South Asian security complex with neighbours China and Pakistan, a complex in which Australia is not regarded as a significant player, notwithstanding its extensive Indian Ocean coastline in Western Australia.”74

India’s security problems with these neighbors constitute an irritant in the relationship between Australia and India. Besides refusing to be caught in a zero-sum game between India and China, Australia—like most ASEAN countries that partner with India—has long feared becoming embroiled in Indo-Pakistani tensions. New Delhi, for its part, criticizes Canberra’s support to Islamabad.

Similarly, although India’s perceptions are beginning to change, Australia does not yet occupy a prominent role in India’s strategic thinking. India expanded its Look East policy in 2003 to other Asia-Pacific countries, including Australia, but Canberra does not seem to enjoy a high degree of priority in New Delhi. Seen from the Indian capital, Australia appears to have little to offer beyond natural resources. In strategic terms, Canberra remains a distant and somewhat junior partner despite efforts by the two countries to give substance to the relationship.

As a result, unlike the economic relationship, security interactions between India and Australia are developing slowly, and the two countries have had difficulty expanding on the areas for cooperation enumerated in their 2009 joint security declaration. Overall, strategic engagement between them has broadened but not deepened.

A Growing Interdependence

In the coming years, the overall relationship between India and Australia will continue to grow. Although its development is unlikely to be spectacular in the strategic domain for the foreseeable future, both countries increasingly matter for each other. One can no longer conclude, as some Australian analysts did in 2001, that Australia and India have only limited bilateral security interests in common and that these shared concerns are not important to each country’s broader strategic outlook.75

While difficulties persist between Canberra and New Delhi, the two have shared interests regarding regional stability. They could and should raise their level of maritime cooperation, especially in Southeast Asia, where their interests overlap.76 The creation in 2012 of an Australia-India-Indonesia troika in the IORA is a step in that direction.77 Similarly, India and Australia could potentially cooperate on nonproliferation and disarmament.

The list of what the two countries could do together on strategic matters is in fact quite long, and it is getting longer as security dialogues multiply. Defense analyst David Brewster, for example, lists eleven domains of potential cooperation, ranging from collaboration in regional institutions to humanitarian and disaster relief efforts to Antarctic research.78 All of the proposed activities would insist on cooperation at all levels, which both countries have agreed to in principle. But the Indian officers and civil servants who are actually in charge of the operational aspects of the relationship are still uncomfortable cooperating with their counterparts from other countries. They need to understand in a practical way that cooperation buys influence and support and is a very effective force multiplier.

The benefits of this sort of cooperation will eventually cause India’s confidence to grow to a point where New Delhi will be able to participate more actively in regional institutions. This could lead, over time, to the upgrading of existing institutions so they address both traditional and nontraditional regional security issues.

Until then, a link between these two levels could be established by targeting specific issues that include both China and the United States. The task force on Indian Ocean security at the Australia India Institute, for example, recommended the adoption of a “new Indo-Pacific regional security regime concept to involve all relevant stakeholders in dealing with matters of regional maritime security, especially those related to the flows of energy through the Indian Ocean.”79

India and Australia have explicitly committed, at least on paper, to increasing their strategic interactions in the Indian Ocean, where their interests both converge and overlap. Significant cooperation in the larger Indo-Pacific region will be more difficult to bring about, as it will require not only increased military capacities but also an evolution of the mindset on both sides.

In the meantime, patience and realistic expectations are central to the construction of a deep strategic relationship. Speaking on the evolution of Australia’s relationship with India, Australian Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Peter Varghese declared in May 2013 that “India punishes impatience,” adding that “if we get the economic relationship right, the strategic partnership will follow, although there will be a long lag between when India arrives as an economic power and when it arrives as a strategic power.”80

As frustrating as this remark may be for the actors in the relationship in the short term, it would be futile to expect a dramatic change in the pace and nature of India-Australia relations overnight. As economic ties increase, so too will the need for a stronger strategic partnership. But the dilemma that currently affects the relationship will persist until both countries strengthen their capacities—or until the need for a strong and immediate partnership is forced upon them by some unforeseen event.

Notes

- David Brewster, “The Australia-India Security Declaration: The Quadrilateral Redux?” Security Challenges 6, no. 1 (Autumn 2010): 1, www.securitychallenges.org.au/ArticlePDFs/vol6no1Brewster.pdf.

- David Brewster, India as an Asia Pacific Power (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 119.

- Meg Gurry, India: Australia’s Neglected Neighbor? 1947–1996 (Brisbane: Centre for the Study of Australia-Asia Relations, Griffith University, 1996), x.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., viii.

- Sally Percival Wood, “So Where the Bloody Hell Are We’: The Search for Substance in Australia India Relations,” Fearless Nadia Occasional Papers on India-Australia Relations, volume 1, Australia India Institute (Winter 2011): 9.

- Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, India Country: Strategy, Australia in the Asian Century, Toward 2025, September 2025, http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/141666/20131015-1509/www.dfat.gov.au/issues/asian-century/india/downloads/india-country-strategy.pdf.

- Ibid.

- See Michael Wesley and Sergei DeSilva-Ranasinghe, “The Rise of India and Its Implication for Australia,” Policy 27, no 3, Spring 2011.

- Task Force on Indian Ocean Security, The Indian Ocean Region: Security, Stability and Sustainability in the 21st Century, Australia India Institute, March 2013, 84, www.aii.unimelb.edu.au/sites/default/files/IOTF_0.pdf.

- Australian Government, Department of Defence, Defending Australia in the Asia-Pacific Century: Force 2030, Defence White Paper 2009, 96, www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper2009/docs/defence_white_paper_2009.pdf.

- “India-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation,” New Delhi, November 12, 2009, www.idsa.in/resources/documents/India-AustraliaJointDeclaration.12.11.09.

- Brewster, “The Australia-India Security Declaration: The Quadrilateral Redux?” 1.

- Ibid., 1.

- Australian Government, Department of Defence, Defence White Paper 2013, 65, www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper2013/docs/WP_2013_web.pdf.

- See “Minister for Defence and India’s Minister of Defence – Joint Statement – Visit of Mr. A.K. 17 Anthony, Defence Minister of India, to Australia 4–5 June 2013,” June 5, 2013.

- For a full list of India-Australia security dialogues, see David Brewster, “The India-Australia Security Engagement: Opportunities and Challenges,” Gateway House, Research Paper no 9, October 2013, 34–35, www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/The-India-Australia-Security-Engagement-Opportunities-and-Challenges.pdf.

- Michael Wesley, There Goes the Neighborhood: Australia and the Rise of Asia (Sydney: University of South Wales Press Ltd., 2011), 3.

- Australian Government, Australia in the Asian Century, White Paper, October 2012, 7.

- Task Force on Indian Ocean Security, The Indian Ocean Region: Security, Stability and Sustainability in the 21st Century, 82–83.

- Ibid., 24–25.

- Sunil Kilnani, Rajiv Kumar, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Lt. Gen. (Retd) Prakash Menon, Nandan Nilekani, Srinath Raghavan, Shyam Saran, and Siddarth Varadarajan, Nonalignment 2.0: A Foreign and Strategic Policy for India in the Twenty First Century. Active officials also participated in the deliberation which preceded the writing of the document.

- Yong Tan Tai and Mun See Chak, “The Evolution of India-ASEAN Relations,” India Review, 8:1, 22–23.

- Quoted in Amitabh Mattoo, “ASEAN in India’s Foreign Policy,” in India and ASEAN: The Politics of India’s Look East Policy, ed. Frederic Grare and Amitabh Mattoo (New Delhi: Manohar, 2001), 106.

- Wesley, There Goes the Neighborhood, 5–6.

- Percival Wood, “So Where the Bloody Hell Are We,’” 1.

- Rory Medcalf, “Grand Stakes: Australia’s Future Between China and India,” in Strategic Asia 2011–2012: Asia Responds to Its Rising Powers, China and India, ed., Ashley Tellis, Travis Tanner, and Jessica Keough (Seattle and Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2011), 195–225, 203.

- Ibid.

- Medcalf, “Grand Stakes: Australia’s Future Between China and India,” 198.

- Daryl Morini, “Why Australia Fears China’s Rise: The Growing War Consensus,” e-International Relations, February 8, 2012, www.e-ir.info/2012/02/08/why-australia-fears-chinas-rise-the-growing-war-consensus.

- See Harsh Pant, “India Comes to Terms With a Rising China,” in Tellis et al. eds., Strategic Asia 2011–2012, 109.

- For a discussion on India’s perception of Chinese activism in the Indian Ocean, see C. Raja Mohan, Samudra Manthan: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2012).

- “Joint Communiqué of the Republic of India and the People's Republic of China,” New Delhi, December 16, 2010, www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/5158/Joint+Communiqu+of+the+Republic+of+India+and+the+Peoples+Republic+of+China.

- Ashok Tuteja, “India, China to Kickstart Maritime Dialogue, to Resume Talks on Nuclear Disarmament, Non-Proliferation,” Tribune News Service, New Delhi, April 13, 2012.

- David Brewster, “Australia and India: The Indian Ocean and the Limits of Strategic Convergence,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 64:5, 560.

- Ibid., 555.

- Medcalf, “Grand Stakes: Australia’s Future Between China and India,” 195–225, 204.

- Ibid., 215.

- Address by H. E. Peter Varghese, Australian High Commissioner to India at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi on May 3, 2012. “Australia-India Strategic Partnership in an Asian Century,” ORF Discourse, Observer Research Foundation, vol. 5, issue 16, June 2012.

- Hugh White, “Australia’s Choice: Will the Land Down Under Pick the United States or China?” Foreign Affairs, September 4, 2013, www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139902/hugh-white/australias-choice.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Nicholas Burns, “Emerging Asia and the Future of the U.S.-Australia Alliance,” paper presented at the U.S.-Australia 21st Century Alliance Project Workshop, Australian National University, Canberra, August 30, 2012; http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/researchschool/emerging_asia/papers/Burns_Future_US_Alliance_paper.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Mahbubani is the former ambassador of Singapore to the United Nations and dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, at the National University of Singapore. See Kishore Mahbubani, “Australia’s Destiny in the Asian Century: Pain or No Pain,” paper presented at the U.S.-Australia 21st Century Alliance Project Workshop, Australian National University, Canberra, July 31, 2012.

- William Cooper and Marl E. Manyin, Japan Joins the Trans-Pacific Partnership: What Are the Implications, CRS Report for Congress, August 13, 2013.

- Gary Smith, “Australia and the Rise of India,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 64, no 5 (November 2010): 566–82, 568.

- Rory Medcalf, “Australia’s Uranium Puzzle: Why China and Russia But Not India?” Fearless Nadia Occasional Papers on India-Australia Relations, volume 1 (Spring 2011): 4.

- Ibid., 6.

- “Australia to Allow Uranium Exports to India,” World Nuclear News, December 5, 2011, www.world-nuclear-news.org/NP-Australia_to_allow_uranium_exports_to_India-0512115.html.

- “Australia Bans India Uranium Sale,” BBC News, January 15, 2008.