As Iran defends its interests in the region and its regime’s survival, it may push Hezbollah into the abyss.

Michael Young

Policymakers need to explore ways to make U.S. foreign policy work better for America’s middle class, even if their economic fortunes depend largely on domestic factors and policies.

All U.S. administrations aim to conceive foreign policies that protect and enhance Americans’ safety, prosperity, and way of life. However, views now diverge considerably within and across political party lines about whether the U.S. role abroad is adequately advancing the economic well-being of the middle class at home. Today, even as the U.S. economy is growing and unemployment rates are falling, many households still struggle to sustain a middle-class standard of living. Meanwhile, America’s top earners accrue an increasing share of the nation’s income and wealth, and China and other economic competitors overseas reap increasing benefits from a global economy that U.S. security and leadership help underwrite.

Policymakers need to explore ways to make U.S. foreign policy work better for America’s middle class, even if their economic fortunes depend largely on domestic factors and policies. However, before policymakers propose big foreign policy changes, they should first test their assumptions about who the middle class is, what economic problems they face, and how different aspects of U.S. foreign policy can cause or solve them. They need to examine how much issues like trade matter to these households’ economic fortunes relative to other foreign and domestic policies. They should acknowledge the trade-offs arising from policy changes that benefit some communities at the expense of others. And they should reach beyond the foreign policy establishment to hear from those in the nation’s heartland who have critical perspectives to offer, especially state and local officials, economic developers, small business owners, local labor representatives, community leaders, and working families.

Policymakers need to explore ways to make U.S. foreign policy work better for America’s middle class, even if their economic fortunes depend largely on domestic factors and policies.

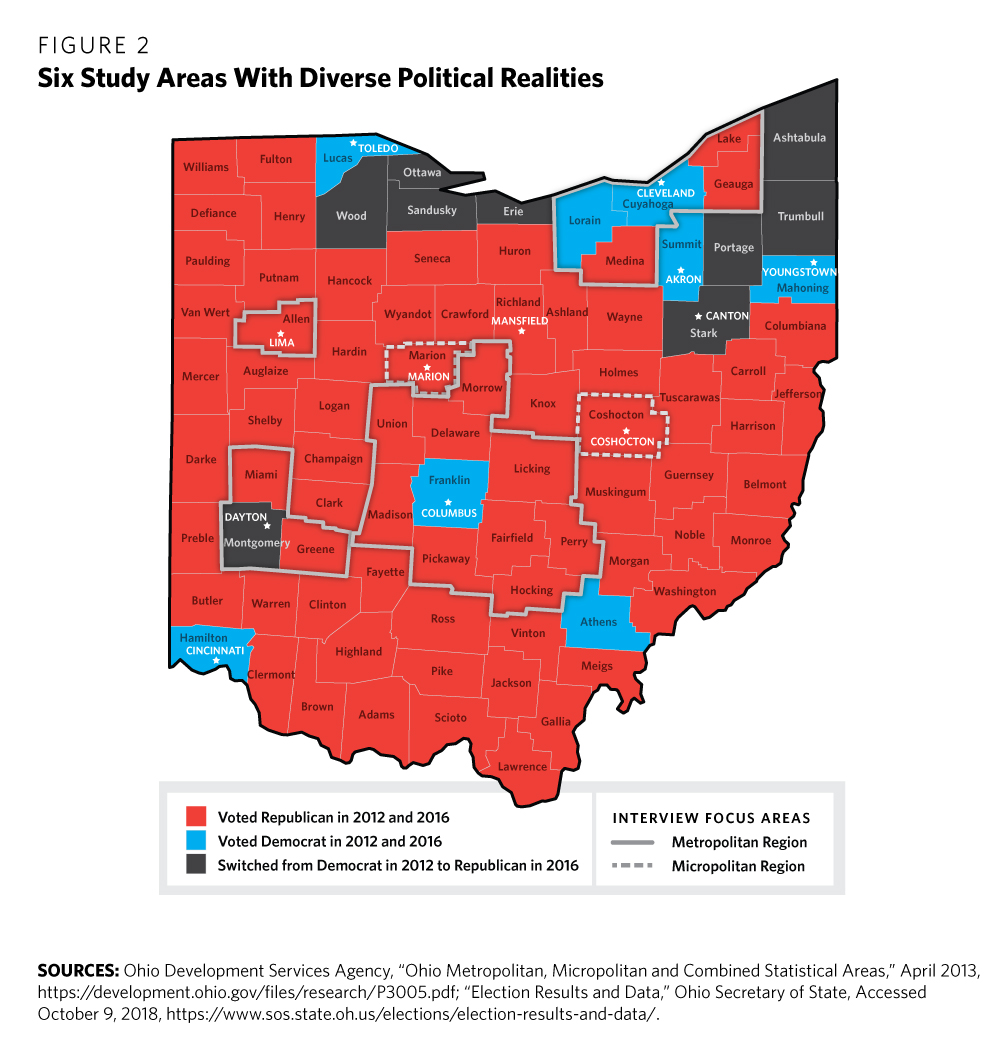

With these objectives in mind, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace launched a series of state-level case studies to determine whether significant changes to U.S. foreign policy are needed to better advance the economic well-being of America’s middle class. Ohio was chosen for the inaugural study because of its economic and political diversity and its well-known status as a bellwether state. Carnegie partnered with researchers at OSU to conduct the study and convened a bipartisan task force comprised of former senior policymakers to provide strategic guidance and shape the findings. Interviews were conducted in Cleveland, Columbus, Coshocton, Dayton, Lima, and Marion to solicit views in diverse conditions across the state.

U.S. national security and foreign policy professionals in Washington, DC, and worldwide strive to sustain U.S. global leadership. Their international economic, trade, commercial, defense, aid, and other foreign policies aim to promote macroeconomic growth and stability and to deliver maximum aggregate benefits for the nation. But many people at the state and local levels are unclear on what all this activity actually entails or how it helps their communities prosper. They worry that policymakers prioritize the concerns of special interests with privileged access and influence. And they mostly depend on big businesses and industry associations to assess the economic implications of U.S. foreign policy—which becomes problematic when the interests of the state’s key industries are at odds with each other or their own workers. Trade-offs assumed to exist between different U.S. states play out within Ohio itself.

Few interviewees feel well-placed to judge how U.S. foreign policy or global leadership, writ large, could work better for Ohio’s middle class. Most can only comment on what is visible to them: trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), and defense spending. And in each of these areas, policy changes that could benefit some might hurt others, depending on unique local economic conditions.

No one is arguing strictly for protectionism or isolationism. But opinions diverge on how best to benefit from trade and globalization, given disparities in how businesses and workers to date have profited and suffered as a result of it.

It is too soon to gauge the implications of the renegotiated NAFTA agreement, now called the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Further, while there will be winners and losers among Ohio’s middle class as a result of tariffs or a “trade war” with China, there is too much uncertainty and insufficient data at this point to declare who they are. In any event, that was not the purpose of this study; however, the quantitative and qualitative data gathered helps to place such debates in a wider context. Five major sets of policy directions and questions emerged that should help inform policymakers’ efforts to make U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class:

These questions leapt out from the data gathered during this study, especially from the micro-case studies conducted in Columbus, Cleveland, Coshocton, Dayton, Lima, and Marion. The answers, however, are less obvious, as they will require policymakers to contemplate major strategic shifts and to choose among starkly different options (see the report’s concluding chapter). Carnegie task force members intend to elaborate on, and add to, these policy options following additional state-level case studies in 2019 and will offer detailed recommendations in a final report in 2020. Meanwhile, the data and dilemmas highlighted in this inaugural study should provide policymakers with food-for-thought—at a time when U.S. foreign policy has reached a critical inflection point.

It is widely recognized that foreign and domestic issues are now powerfully joined. But we need to fully understand how they intersect and what that means for the world. Earlier this year, the Geoeconomics and Strategy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace launched a series of case studies to help policy experts answer this fundamental question:

Are significant changes to U.S. foreign policy required to better advance the economic interests of America’s middle class?

Leading up to the U.S. presidential 2020 election, candidates will be seeking direction on how best to address Americans’ struggles amid uncertain domestic and global environments. However, before policy experts across the political spectrum share their views, they should first test their long-held assumptions about the economic fortunes of America’s middle class and how various U.S. foreign policies may impact them. Local economies across the country look very different today than they did in past decades, and sticking with traditional approaches, or radically departing from them, might ultimately do more harm than good.

Local economies across the country look very different today than they did in past decades, and sticking with traditional approaches, or radically departing from them, might ultimately do more harm than good.

To this end, Carnegie’s case studies are designed to capture additional data and different perspectives from U.S. states across the nation’s heartland. As this first study shows, the findings could usefully inform the development of more comprehensive strategies. They could also help those who generally see the world through the prism of geopolitics and security but wish to pay more attention to economic developments at home. More broadly, they may be useful for explaining the domestic determinants of U.S. foreign policy to local officials, business communities, and the general public, as well as to foreign counterparts overseas.

Carnegie has assembled a bipartisan task force of former national security strategists, foreign policy planners, trade negotiators, and international economic experts to provide strategic direction to the studies and shape their main findings. The views of these former senior officials, who served in prior Republican and Democratic administrations, diverge considerably on individual foreign and domestic policies. But they share a common desire to take a fresh look at their assumptions about how the U.S. role abroad impacts the fortunes of America’s middle class at home. (See Box 1 for how foreign policy and the middle class are defined in this report.)

Foreign policy serves as shorthand in this report for the spectrum of foreign, defense, development, international economic, trade, and other policies that guide the work of American diplomats, soldiers, trade negotiators, aid experts, and commercial advocates.

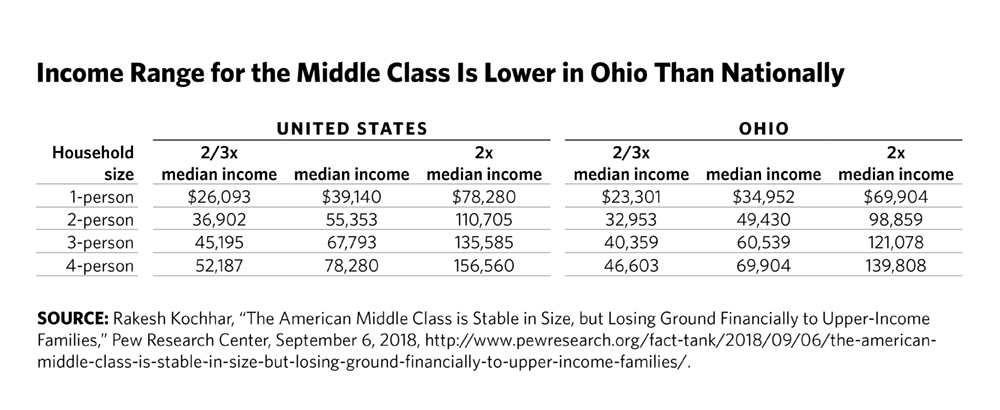

Middle class or middle income in this report refers to households earning an income that is two-thirds to double the U.S. median annual income, adjusted for household size and local cost of living (lower-income households have incomes less than two-thirds of the median; upper-income households have incomes that are more than double the median).1 According to this widely recognized definition—employed by the nonpartisan, nonadvocacy Pew Research Center—the 2016 income range for the middle class in the United States—and in Ohio for comparison—is as follows:

These ranges vary when adjusted for local cost of living and household size. They are also very broad and hence just a starting point for discussion; those people at the top end of the middle-income bracket likely experience very different realities than those at the bottom. Furthermore, as Pew acknowledges, income is an incomplete gauge. A recent poll reveals that Americans’ definition of the middle class is based on many other factors, too, including their ability to hold a secure job, save money, take a vacation, own a home, and earn a college education (in order of importance).2

1 Pew Research Center, “America’s Middle Class Is Losing Ground,” December 9, 2015, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/09/the-american-middle-class-is-losing-ground/; Pew Research Center, “America’s Shrinking Middle Class: A Close Look at Changes in Metropolitan Areas,” May 11, 2016, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/05/11/americas-shrinking-middle-class-a-close-look-at-changes-within-metropolitan-areas/. For a good overview of the many different definitions of the middle class, see Richard Reeves, Katherine Guvot, and Eleanor Krause, “Defining the Middle Class: Cash, Credentials, or Culture?,” Brookings Institution, May 7, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/defining-the-middle-class-cash-credentials-or-culture/.

2 Anna Brown, “What Americans Say It Takes to Be Middle Class,” Pew Research Center, February 4, 2016, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/04/what-americans-say-it-takes-to-be-middle-class/.

U.S. diplomats and elected officials have long touted the middle class as the backbone of the country and the shining success story of America’s political and economic models. But America’s middle class has been steadily hollowing out over the last several decades (see Figure 1).

While the percentage of American households considered to be middle class has stopped shrinking in the last several years, and incomes rose for those in the lower-, middle-, and upper-income households between 2010 and 2016, the decades-long trend continues of those in the upper-income bracket steadily accruing an increasing share of the nation’s income and wealth.1 The median income of three-person households in the lower-income bracket in 2016 ($25,624) was less than in 2000 ($26,923); it was about the same for middle-income households in 2016 and 2000 ($78,442). Only the median incomes of upper-income households increased from 2000 ($183,680) to 2016 ($187,872).2 In 1983, the upper-income net worth was 3.4 times greater than the median net worth of middle-income families, but by 2016, it was 7.4 times greater.3

The distributional trends for middle-class American households may partly explain why people are increasingly arguing that the system is rigged in favor of those at that top. Moreover, it could explain why some working families are amenable to policy changes, including in foreign policy, while those in the top income bracket defend the status quo.

But these distributional trends and perceptions of fairness are only part of the story. The escalating costs for healthcare, childcare, and education, among other major household expenditures, have transformed what it means to be earning a middle income. As families struggle to meet the unavoidable costs for basic necessities, they are forced to reconsider taking a vacation, renovating a home, buying a new car, retiring when planned, or paying down household debt. A middle-class standard of living several decades ago did not entail having to make such trade-offs.

Attaining a comfortable middle-class standard of living today may require being in the upper-middle income bracket, if not the upper-income bracket, depending on the local costs of living. But it is increasingly difficult to climb into those ranks with only a bachelor’s degree—and especially so without one. Working families accordingly maintain sober expectations about their long-term economic future, even as economic growth rates climb, unemployment levels drop, and business and consumer confidence soar in the near term.

Many solutions to the longterm economic challenges confronting America’s middle class lie in changes to domestic policies on taxes, education, worker training, healthcare, childcare, pensions, family leave, occupational licensing, housing, infrastructure, transportation, and corporate governance.

Many solutions to the long-term economic challenges confronting America’s middle class lie in changes to domestic policies on taxes, education, worker training, healthcare, childcare, pensions, family leave, occupational licensing, housing, infrastructure, transportation, and corporate governance. These issues will remain subjects of debate within and across party lines. President Donald Trump argues that the United States more importantly needs a different foreign policy—an America First foreign policy—to help the middle class. At least with respect to trade policy, he is not alone. A sizable number of Democrats and Republicans share Trump’s view that free trade agreements brokered by past administrations have not served American workers as well as they should have, even as they question his negotiating tactics and oppose many other aspects of his domestic and international agendas.

Thus, we have arrived at an inflection point for U.S. foreign policy. Some core tenets of the U.S. role abroad are being called into question because important political actors, on both sides of the aisle, believe these tenets no longer serve the interests of America’s middle class. U.S. foreign policy ambitions of past decades now appear to be in tension with economic realities at home, in stark contrast to their convergence in the aftermath of the Second World War.

American and European leaders had already begun thinking about establishing a Western-led international order following the Great Depression and the emergence of authoritarian blocs in the interwar years.4 But the emergence of the Soviet threat in the late 1940s, following the Second World War, provided a clear, strategic rationale for the United States to build up its defenses, extend a security umbrella over European and Pacific allies, and invest in their postwar economic reconstruction. America needed to build up “the West” as a bulwark against the spread of communism and Soviet aggression.

U.S. political leaders relied on an exceptional and unique set of circumstances to sell a reluctant American public on the imperative for assuming major leadership responsibilities abroad. In addition to the Soviet threat that provided a strategic rationale, the effects of the Second World War provided an economic rationale, too. The war effort had helped to power parts of the U.S. economy, while largely destroying the productive capacities of economic competitors in Europe and Japan. Thus, U.S. economic assistance to nations after the war served to create more markets overseas for U.S. products, with little to fear from foreign import competition. It therefore demonstrably advanced U.S. economic prosperity.

In the post-Depression era, workers making up America’s expanding postwar middle class enjoyed higher wages—thanks in no small part to the power of collective bargaining they enjoyed through high rates of union participation. Major U.S. industries could afford to pay higher wages because of minimal foreign competition. Moreover, both businesses and workers reaped benefits from higher levels of government spending on education and infrastructure during president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal era of recovery programs.

The broad prosperity and economic security enjoyed by the American middle class in the quarter century following the Second World War laid a strong foundation at home for the United States to exercise global leadership overseas. Such leadership included the United States brokering the world’s first truly global trade agreement, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The United States served as the chief architect and underwriter of international institutions, including the United Nations (UN), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These institutions helped give universal legitimacy to principles at the heart of the U.S.-led Western order. They acted as force multipliers in support of U.S. foreign policy, providing a vehicle for international burden-sharing. The UN’s existence also provided a framework for managing great power competition, even though Cold War dynamics prevented the Security Council and other UN bodies from realizing their full potential.

From the late 1940s to the 1960s, the United States did indeed have a “grand strategy” that married its foreign policy goals with its domestic economic realities. But the strategy began to fray in the 1970s, prefiguring a shift in the 1980s toward the diminished role of the state, financial liberalization, and globalization. U.S. economic aid and favorable terms of trade granted to Europe and Japan succeeded in accelerating the countries’ resurgence. However, it also hastened their arrival by the 1970s in the United States as fierce economic competitors, at precisely the time when the country was facing mounting economic, political, and social strife. As foreign competition rose, the interests of major U.S. manufacturers looking to decrease costs, and those of organized labor seeking to sustain higher wages and benefits, came to a head. Fissures within the Democratic Party also emerged. The nation made strides to combat racial discrimination as the civil rights movement gained steam. But in the process, many southern Democrats migrated to the Republican Party, dealing a blow to the political coalition on which Roosevelt had relied to build the New Deal.

From the late 1940s to the 1960s, the United States did indeed have a “grand strategy” that married its foreign policy goals with its domestic economic realities. But the strategy began to fray in the 1970s, prefiguring a shift in the 1980s toward the diminished role of the state, financial liberalization, and globalization.

This was happening as economic growth slowed and unemployment and inflation—“stagflation”—soared. The Vietnam War, in addition to claiming tens of thousands of American lives, divided the nation and added to skyrocketing national debt. Facing severe fiscal challenges, the United States abandoned the Bretton Woods arrangements that fixed exchange rates to the U.S. dollar and constrained global capital flows. And trust in government itself eroded during the Vietnam War and the Watergate political scandal. The United States appeared to be in decline—its relative advantages receding—and, hence, policymakers wavered between détente and confrontational foreign policy.

The end of the Cold War created a new geopolitical reality in the 1990s. The United States emerged as the lone global superpower in a more peaceful world. Then president George H.W. Bush put forward a vision for a “New World Order” led by the United States. No longer facing an existential threat from overseas, U.S. leaders faced growing domestic demands to prioritize festering economic challenges at home.

Democratic and Republican administrations in the 1990s and 2000s responded to these pressures by trying to build a foreign policy that would promote economic prosperity. They assumed that the transition to an open, integrated global economy, with the full inclusion of economies around the world, including a rising China, would power global economic growth and create new opportunities for U.S. exports and investment. They moved to leverage the advantages of an integrated North American production platform to compete more effectively in the new global economy. And they tried to transition the previous U.S.-led Western order—which had helped bind America’s allies and partners together through open trade, shared values, and collective action on common security challenges—into a U.S.-led international order. They sought to get Russia and China on board with such an order, rather than exclude them from it—to ultimately create a shared stake in the global order and broaden the international coalition to help counter transnational threats. As a result, the United States would be able to reduce its spending on defense and great power competition; increase domestic investments in education, infrastructure, other long-term productivity factors, and wage growth; and ultimately balance its budget.

However, the U.S. embarked on this path without repairing the social compact among government, business, labor, and communities that had begun to fray in the 1970s. The pro-growth strategies delivered windfall profits for corporate shareholders and those in the upper-income bracket, while wages for rank-and-file employees stagnated. The new global market created enormous new opportunities for U.S. businesses to sell products and services abroad, but it also thrust American workers into competition with China, Mexico, and other low-wage countries. Many communities lost their main sources of economic activity due to outsourcing and offshoring.

Furthermore, the United States was eventually forced to increase defense spending—first due to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq following the September 11 terrorist attacks and then due to the resurgence of geopolitical competition with China and Russia. The combination of unfunded wars, increased defense spending, escalating costs for entitlement spending in an aging nation, and tax cuts once again led to skyrocketing national debt, adding to the nation’s fiscal challenges as it confronted the Great Recession.

Today, there is confusion at home and abroad about the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy. The post–Cold War era appears to have come to an end. Any hopes of revitalizing the more peaceful and prosperous U.S.-led “New World Order” envisaged three decades earlier have given way to deep anxieties about what lies ahead in a more contested strategic environment.

Many across the political spectrum are arguing for reinvigorating the Western alliance to contend with resurgent geopolitical competition with China and Russia. They are also calling for tougher action to combat mercantilist and unfair Chinese trade practices. But they appear ambivalent, conflicted, or divided over the core tenets of previous U.S. strategies to unite “the West.” These core tenets once included leaving no doubt about U.S. security guarantees for allies; actively supporting a Europe that is whole, free, and at peace; strenuously defending democracy and human rights; leading and maintaining a united front in international institutions to advance shared interests and values; and promoting free trade.

The Trump administration’s national security strategy documents indicate that these principles continue to guide U.S. foreign policy, albeit with key adjustments expected with the transition from a Democratic to a Republican administration and with the changes in the strategic environment. But the core underlying principles, which have guided U.S. foreign policy over the last several decades, appear to reflect more continuity than change.5

Trump’s own interpretation of his America First foreign policy, however, entails a more dramatic break from the past. He is not just pushing allies of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to spend more on their own defense, as previous presidents have done, but is also calling into question the fundamental benefits the United States derives from alliances. He is pressing China on unfair trading practices—for which there is broad support across the political spectrum (for the goal, not necessarily the tactics). But he is also imposing tariffs on imported steel and aluminum from allies and has at various moments threatened tariffs on imported automobiles and auto parts on national security grounds. And he continues to propose massive cuts to U.S. foreign aid and contributions to international organizations. These are just some of the major changes to U.S. foreign policy he is pursuing in the name of advancing the economic well-being of American workers and families.

The relationship between U.S. foreign policy and middle-class well-being now commands center stage, at a time when the trajectory of the U.S. role in the world has come to an inflection point. Would a significant change to U.S. foreign policy, whether along the lines of Trump’s America First policy or otherwise, address the causes of the economic struggles American families face? Relative to domestic policies, how much does U.S. foreign policy really matter to the economic well-being of the American middle class? How do the domestic and international agendas fit together? These are some of the big questions explored in this study, as part of a larger effort to identify ways to make U.S. foreign policy work better for the American middle class.

This report begins to tackle the above questions from the ground up, using Ohio as a compelling first case study. Ohio once represented what journalist Neal Peirce described in the 1970s as “the personification of the Middle Class Society” in America.6 Today, Ohio’s economic and political dynamics represent a microcosm of the country itself. Some of its cities, such as Cincinnati and Columbus, are prospering as they attract young, educated talent and global investors to a modern, diversified twenty-first-century economy. The state has rural areas thriving with productive farms and agribusiness. And it boasts abundant shale resources and hosts military facilities and units that are critical to the nation’s security and the state’s economy.

Yet Ohio also has inner cities and rural areas under stress. There are towns struggling to reinvent themselves after the devastation of their twentieth-century manufacturing facilities due to automation and trade. The state confronts resource constraints to upgrade critical infrastructure and upskill its workforce.

Altogether, Ohio’s regions and congressional delegation span the political spectrum of conservative Freedom Caucus members, traditional Republicans, moderate Democrats, and social and economic progressives. Since 2010, it has been led by a Republican governor with a national profile whose politics defy neat categorization. And, as is often said, Ohio remains a bellwether state. Every presidential candidate since 1964 who won Ohio captured the White House, including Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016.

To further understand Ohio’s increasingly diverse economic interests and challenges, Carnegie partnered with OSU’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs. The college has been leading several research efforts on the future of Ohio’s economy and its middle class, including through the Toward a New Ohio project and Alliance for the American Dream project. To provide additional core input on Ohio’s realities, the school convened researchers associated with those efforts, enlisted the expertise of its leading academic authorities on Ohio’s economy, and drew on its statewide networks.

There is a rich debate taking place within the Washington, DC–based foreign policy establishment about the future direction of the U.S. role abroad. This study introduces some less familiar voices and viewpoints into the mix. It seeks to expose those in the nation’s capital responsible for developing and implementing foreign policies to the diverse perspectives Ohioans express on international issues affecting the middle class. The aim is not to sell Ohio on any particular set of policies devised in Washington. Rather, it is to sell Washington on the need to better understand the aspirations of middle-class families and communities in Ohio, the constraints they face, and the perceptions they hold about how U.S. foreign policy affects their interests.

Recent research undertaken by the team at OSU provided the foundation for this study, particularly three papers published by the John Glenn College as part of its Toward a New Ohio project. William Shkurti, a former budget director in Ohio’s state government, and Fran Stewart, an Ohio-based former journalist and current public policy researcher on regional economic development, authored the papers.7

To supplement the research, several dozen interviews and focus groups were conducted across Ohio with state officials, heads of economic development associations, entrepreneurs, small business owners, local labor leaders, and local civic organizations. The team at OSU—which included Professor Ned Hill, a leading expert on Ohio’s manufacturing industry—drew up the list of interviews. Fran Stewart, who is based in Cleveland but grew up near southern Ohio’s Appalachian region, organized and led the interviews and focus groups. Members of Carnegie’s Geoeconomics and Strategy Program joined many of them. The interviews took place in six communities representing Ohio’s distinct regions: Cleveland, Columbus, Coshocton, Dayton, Lima, and Marion. This allowed the study team to capture perspectives from (1) big cities that drive much of the state’s economy, yet are very different from each other; (2) smaller cities that are thriving or struggling to reinvent themselves; and (3) more rural counties with different economic outlooks. The mix of communities also ensured that the interviews spanned areas that voted for Trump and areas that voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, by both overwhelming and narrow margins (see Figure 2).

Members of Ohio’s congressional delegation and their staffs, as well as DC-based national business and trade associations and labor organizations, all possess extremely valuable perspective on the issues in question. Task force members briefed some of these representatives on this effort and benefited from their informal advice. But no Washington-based officials were included among the formal interviews, because priority was given to shedding light on local perspectives.

The interviews conducted in Ohio constitute a very important input to this study. They prompted and provoked review of academic literature and government statistics. They provided concrete anecdotes and examples to make general points more specific. And they informed the report’s focus and organization. However, the study’s findings and conclusions are not based on the interviews alone. The interviews represent a relatively small sample size. And, as diverse as the locations were, different perspectives may have emerged in other locations, such as Akron, Ashtabula, Athens, Cincinnati, Toledo, and Youngstown.

Key messages emerging from the interviews fell into three broad categories:

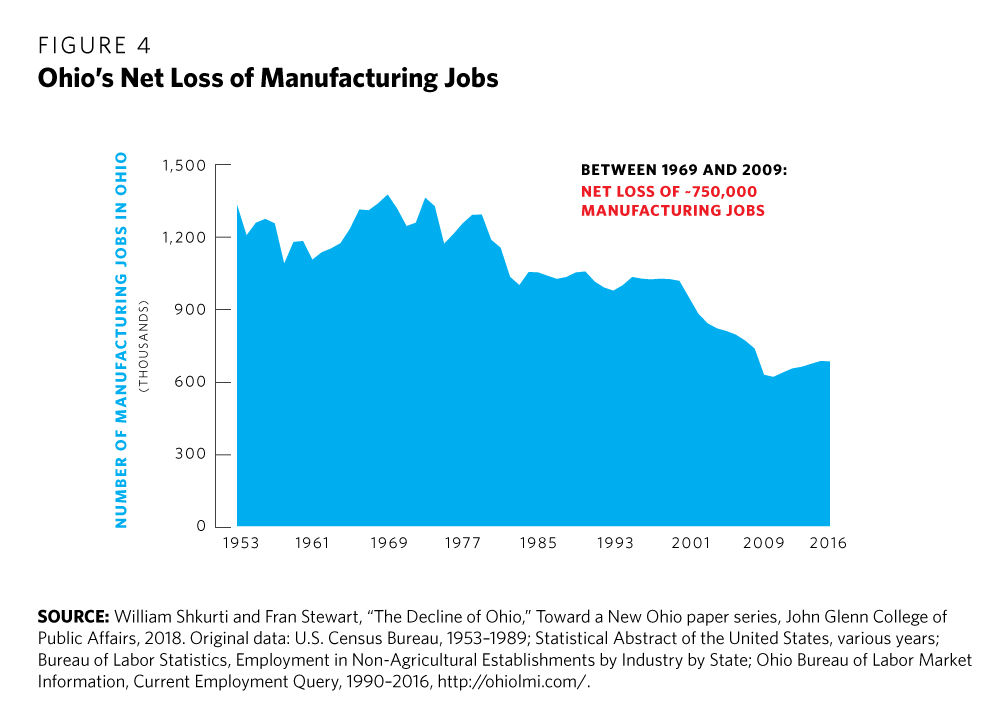

The reading of the past matters. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan clearly speaks to many Ohioans’ sense of nostalgia and grievance about a time when the state led the nation in delivering good-paying manufacturing jobs that made a middle-class lifestyle accessible to most households (with the notable exception of people of color and other marginalized groups). Many describe the net loss of approximately 750,000 manufacturing jobs between 1969 and 2009 as centrally relevant to the decline of Ohio’s middle class.8 But views diverge considerably over the degree to which trade policy created that outcome relative to other factors, such as automation and domestic competition. In reality, the cause of manufacturing job losses was not an either/or proposition, as some of the national-level debate sometimes implies. The relative weight of different factors varied across time and place over the past fifty years.

To better understand how trade policy and other factors contributed to shaping Ohio’s economy, Chapter Two describes the transformation of Ohio’s manufacturing sector over the last half century, drawing on state-based and national-level research. This historic grounding helps illustrate why a focus on trade alone does not do justice to the full range of struggles various communities confront in the twenty-first-century economy. It also helps shed some light on why the debates over trade with China, the future of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and the renegotiation of NAFTA have been so contentious and emotionally fraught. Due to the recentness of the renegotiation of NAFTA, this report does not comment on the effect it will have on Ohio’s middle class.

Most interviewees clearly identified themselves as globally oriented, in favor of foreign investment and fair trade on a level playing field and adamantly opposed to seeing the world in zero-sum terms.

Present realities matter even more. Virtually all interviewees, including those most wistful about the past, emphasized the need for those in Washington, DC, to devise international policies that reflect the circumstances Ohio’s middle class now faces. They understand that the manufacturing sector will never account for the same proportion of high-paying middle-class jobs that it did in the 1950s. Yet, at the same time, they stressed how Ohio’s manufacturing sector and its economy more generally have come a long way since the early 1980s, when the now resented and outdated “Rust Belt” label emerged. The structure of Ohio’s economy and its outlook in 2018 are very different than they were in earlier decades. Chapter Three focuses on the opportunities and challenges arising for the middle class in Ohio’s increasingly diversified economy. State officials will have to contend with a broad range of domestic policy dilemmas as they work to create good-paying jobs, make more Ohioans qualified for those jobs, and help support the working poor and those left behind by the modern economy.

Policies that account for places with diverse circumstances and challenges matter most. The six micro–case studies of Columbus, Cleveland, Dayton, Lima, Marion, and Coshocton, as detailed in Chapter Four, illustrate vividly the divergent fortunes of cities and towns in a changing global economy. There is clearly no single significant change to U.S. foreign policy that will advance the economic interests of the middle class, because those interests themselves vary. However, caricatures of the opposing interest of those in Trump and Democratic strongholds do not appear to reflect reality. Ohioans are not neatly divided into camps: isolationists versus globalists, protectionists versus free traders, supporters of a zero-sum versus positive-sum world. Most interviewees clearly identified themselves as globally oriented, in favor of foreign investment and fair trade on a level playing field and adamantly opposed to seeing the world in zero-sum terms. The differences among Ohioans’ opinions were more nuanced, as elaborated in their own words in Chapter Four, which is the heart of this report.

Based on the data and perspectives underlying these themes, as well as their own experiences in government, task force members identified five sets of policy directions and questions that policymakers will need to grapple with to better advance the economic well-being of America’s middle class. Elaborated in greater detail in Chapter Five, they center on:

1 Rakesh Kochhar, Pew Research Center, “The American Middle Class Is Stable in Size, but Losing Ground Financially to Upper-Income Families,” September 6, 2018, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/06/the-american-middle-class-is-stable-in-size-but-losing-ground-financially-to-upper-income-families/.

2 Ibid.

3 Pew Research Center tabulation of Survey Consumer Finances public-use data. Rakesh Kochhar, Pew Research Center, “Wealth Gap Is at Highest Record Level” in “The American Middle Class,” presented to the Carnegie Task Force, Washington, DC, November 17, 2017.

4 This historical review of the intersection of U.S. foreign and domestic policy in the post–Second World War and post–Cold War eras draw from, and are informed by, the following sources:

Rawi Abdelal and John G. Ruggie, “Chapter 7: The Principles of Embedded Liberalism: Social Legitimacy and Global Capitalism,” in New Perspectives on Regulation, ed. David Moss and John Cisternino (Cambridge, MA: The Tobin Project, 2009).

Hal Brands, What Good Is Grand Strategy? Power and Purpose in American Statecraft From Harry S. Truman to George W. Bush (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014).

Hal Brands, American Grand Strategy in the Age of Trump (Brookings Institution Press, 2018).

Hal Brands, Making the Unipolar Moment: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Rise of the Post-Cold War Order (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018).

Jefferson Cowie, Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2010).

John Ikenberry, “The Myth of Post-Cold War Chaos,” Foreign Affairs 73, no. 3 (May/June 1996): 79-91.

Jonathan Kirshner, American Power After the Financial Crisis (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014).

Dani Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2011).

5 “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” December 2017, White House: Donald J. Trump, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf.

“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge,” January 2018, Department of Defense: James Mattis, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

6 Neal Peirce, The Megastates of America: People, Politics and Power in the Ten Great States (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 299.

7 William Shkurti and Fran Stewart, Toward a New Ohio paper series, The John Glenn College of Public Affairs, 2018, http://glenn.osu.edu/toward-a-new-ohio/.

8 William Shkurti and Fran Stewart, “The Decline of Ohio,” Toward a New Ohio paper series, The John Glenn College of Public Affairs, 2018, http://glenn.osu.edu/toward-a-new-ohio/.

Ohio experienced an estimated net loss of 750,000 good-paying manufacturing jobs between 1969 and 2009.1 Why did that happen, and what were the consequences for middle-class households and communities across the state? Policymakers seeking to build broad-based support for their trade agenda must grapple with this question.

According to OSU’s research, foreign trade accounted for no more than one-third of these manufacturing job losses in Ohio; a far greater number resulted from other factors, notably automation and domestic competition with other states.2 It is vital to understand how these nontrade-related factors impacted Ohio’s manufacturing employment over the last several decades, in order to appreciate why the economic well-being of blue-collar workers in Ohio cannot be advanced though adjustments to trade policy alone.

That said, it would be a serious mistake to minimize the impact of the trade-related manufacturing job losses. Everyone who lost a job due to outsourcing, offshoring, or import competition had family, neighbors, and local shops dependent on their businesses. Entire communities were devastated. Several hundred thousand Ohioans were directly or indirectly affected. And for many of them, this was not just about the loss of employment, but also the gradual unraveling of a de facto social contract that once existed between government, business, labor, and communities.

This chapter provides an account of how Ohio’s middle-class fortunes became intertwined with manufacturing jobs in the 1950s–1960s. It reviews how so many of those jobs were subsequently lost in successive decades, due to both trade- and nontrade-related factors. And it examines the record of TAA programs aimed at easing the pain.

Ohioans point to the 1950s and 1960s as the economic golden years for the middle class. Most job seekers in those days did not need a college degree or advanced education to land secure employment that paid a decent wage. Such middle-class jobs allowed Ohio workers to buy a house in a safe neighborhood, send their children to respectable public schools and local colleges, access employer-provided healthcare, take a yearly family vacation, and save for retirement.3 These Ohioans had every expectation that their children would climb even further up the economic and social ladder than they had. At the time, that is what it meant to be middle class in Ohio (African Americans, who represented 8 percent of the state’s population at that time, did not, of course, experience the “middle-class dream” in the same way).4

In the mid-1950s, manufacturing jobs accounted for almost half of all employment for Ohio’s workforce. The manufacturing jobs paid 5 percent to 10 percent more per hour than other jobs performed by un- and semi-skilled workers, and they were generally accompanied by generous healthcare, leave, and retirement benefits.5 Unionized workers in the automotive, rubber, and steel industries, which were concentrated in Ohio and the industrial Midwest, managed to secure even higher wages and benefits.6

Manufacturing firms could afford to pay the higher wages and provide good benefits for several reasons: they profited from the high demand for automobiles, consumer appliances, and other manufactured products that resulted from growing families and suburbanization in the post-Depression era; the firms experienced high levels of productivity growth as they reaped the benefits of higher levels of government spending on education, infrastructure (including the interstate highway system), and improvements in electrification;7 and they faced little foreign competition because the productive capacities of Europe and Japan had been decimated by the Second World War. Finally, the auto, steel, and rubber industries in the Midwest enjoyed favorable antitrust protection from Congress.8

For these various reasons, Ohio enjoyed a per capita income exceeding the national average through the 1950s and 1960s. However, Ohio’s per capita income dropped below the national average in 1969 and declined steadily for the next half-century. That drop coincided with the estimated net loss of 750,000 manufacturing jobs from their peak of almost 1.4 million in 1969 (see figures 3 and 4).

U.S. manufacturing employment nationwide suffered as the United States experienced recessions (in 1970 and from 1973 to 1975) and as unemployment and inflation—stagflation—rose astronomically. The economic challenges of the 1970s and early 1980s stemmed from various domestic factors, which policymakers responded to with major shifts in monetary and fiscal policy. However, geopolitical shocks, foreign economic competition, and foreign policy also played significant roles.

Initially, the buildup to the Vietnam War—which was part of an ideological battle to defend democracy and free markets from the spread of communism—brought additional business to Ohio factories. However, as the war dragged on, its effect on the economy turned negative. Its mounting costs—on top of increased government spending for Medicare and other domestic programs under then president Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiatives—exacerbated the nation’s fiscal problems. The spending contributed to mounting inflation and increased interest rates, depressed investment, and high dollar valuation (albeit with a brief sharp drop when the United States abandoned the gold standard)—to the detriment of exports.9

Former president Richard Nixon’s administration had to contend concurrently with crises in the Middle East as it dealt with the Vietnam War. The United States had been building close security and economic cooperation in the Middle East, particularly with Saudi Arabia, for decades. The intention was to strengthen shared opposition to the spread of communism and increase and sustain the steady supply of affordable oil. Despite close U.S.-Saudi relations, however, the United States could not prevent the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) from declaring an oil embargo in 1973, exacting a toll on countries perceived to be supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The OAPEC-induced oil crisis contributed to the recession of 1973–1975, which hit the manufacturing sector hard.10

The economic challenges of the 1970s and early 1980s stemmed from various domestic factors, which policymakers responded to with major shifts in monetary and fiscal policy. However, geopolitical shocks, foreign economic competition, and foreign policy also played significant roles.

Unlike much of the rest of the nation’s manufacturing sector, where employment ultimately rebounded in the mid-1970s and peaked in 1979, Ohio’s manufacturing sector did not. The dominance of the auto, steel, and rubber industries in Ohio accounted for much of this variance. These industries enjoyed antitrust protection, but it came with a downside: diminished imperative to innovate.11 Even as the economy recovered, they still faced severe challenges from increased foreign and domestic competition and evolving demand for steel, and they were more sensitive to energy prices and currency fluctuations.

In terms of increased foreign competition, U.S. efforts to support the economic reconstruction of Europe and Japan after the Second World War created new markets for U.S. products and helped resist Soviet expansion. However, this support also produced stronger competitors for U.S. manufacturers. Between 1950 and 1970, the European Community (EC) tripled its steel production.12 In 1959, U.S. steel consumers began importing foreign steel when domestic producers could not meet the demand during a 116-day shutdown led by North America’s largest industrial union, United Steelworkers.13 In the 1960s and early 1970s, Japan emerged as a major player in the international steel market, achieving its peak production by 1973.14 Throughout the remainder of the 1970s and early 1980s, Japanese industries benefited from their government’s support, and as a result, Japan widened its edge in productivity over both the EC and the United States in terms of output per worker.

Ohio steel manufacturers also faced increasing domestic competition. Beginning in the 1960s, “mini-mills” sprang up in the South and West of the country. These small, nonintegrated plants leveraged modern technology that required less labor than traditional steelmaking technologies, lower operating costs due to recycling scrap into various rolled steel products, and less restrictive work rules to reap high profits and market share. The plants increased their share of U.S. steel production manifold times in the 1970s and early 1980s, while the industry as a whole suffered a slump in demand. Mini-mill products successfully competed with steel from Ohio’s integrated mills in the construction market. And alternative materials to steel emerged in auto parts, appliances, construction, and consumer products.15

These factors visibly came to a head on September 19, 1977—“Black Monday”—when the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company shuttered its Campbell Works, instantly laying off some 5,000 workers.16 That was the first of five major steel mill closures in the area by 1981. In addition to the thousands of mill workers who lost their livelihoods, thousands more workers lost jobs in construction, railroading, trucking, steel fabrication, and other businesses connected to the steel mills. As fewer workers from these industries had money to spend in Youngstown and the surrounding Mahoning Valley towns, the local restaurants, retail shops, and other services also felt the economic pain. Within a decade, the region lost 40,000 manufacturing jobs. The region’s tax base dwindled, restricting resources for local schools, social services, and economic development.17

As this crisis was unfolding in Youngstown, the nation at large was contending with mounting inflation, which had reached 11 percent by 1979.18 In response, the Federal Reserve Bank tightened the money supply, allowing the federal funds rate to approach 20 percent. The recession of 1981–1982 followed, pushing unemployment to 11 percent. It was the worst economic downturn experienced between the end of the Second World War and the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Manufacturing and construction businesses in Ohio were hit especially hard.

Against this backdrop, at a 1984 campaign stop at the Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) Steel plant in Cleveland, Ohio, then presidential candidate Walter Mondale criticized incumbent president Ronald Reagan’s decision to lift quotas on Japanese steel imports and claimed that “Reagan’s policies are turning our industrial Midwest into a ‘rust bowl.’”19 The media adjusted Mondale’s term to Rust Belt, which played off better against Sun Belt, a term coined to describe the U.S. Southeast and Southwest.

Not long after Mondale coined the Rust Belt term, the U.S. economy began growing again and Ohio’s manufacturing sector began to recover and stabilize. The shocks of the 1970s spurred industry restructuring and innovations that restored competitiveness. The loss of Ohio manufacturing jobs to domestic competition slowed. In 1967, Ohio accounted for 7.3 percent of U.S. manufacturing jobs, but by 1990, it only accounted for 5.4 percent; it has remained at or near that level since.20

The U.S. auto industry also eventually managed to claw back some of the market share it had lost in the 1970s and early 1980s. The revamped auto industry did not, however, revert to providing the type of employment it had offered prior to the 1970s, when it faced little competition from German and Japanese imports. As the industry bounced back in the 1980s, auto plants became more efficient, employing fewer workers, but foreign automakers began locating production in the United States. Thus, the local labor market effects played out unevenly in Ohio.21 Communities such as Marysville and East Liberty benefited greatly when Honda established facilities there and created 14,000 jobs. But Lordstown saw employment at its General Motors plant drop from a peak of 12,000 employees in 1985 to fewer than 2,000 today. Cleveland, Dayton, and Mansfield lost entire auto plants.

NAFTA went into effect in 1994. Republican and Democratic presidents negotiated it over several years, taking into account economic as well as national security and political considerations. It was assumed that the agreement would help secure the southwestern border by improving relations with Mexico and creating more economic opportunities for their citizens, thereby incentivizing Mexicans to remain in their country.22

Intense debate remains about the economic impact of NAFTA on Ohio’s middle class. Some of NAFTA’s staunchest critics contend it cost tens of thousands of jobs in Ohio and pushed down wages, as displaced workers had to take lower-paying jobs in other sectors.23 Union representatives also explain that NAFTA led to reduced wages in the manufacturing industry, as the threat of offshoring undercut unions’ negotiating position.24 NAFTA’s defenders counter with the benefits: boosting exports of agricultural products and services among many others; making North American manufacturers more competitive in the global market, thereby saving jobs in the long term; and making more products available to American consumers at more affordable prices. Defenders explain that many of the near-term job losses would have been eliminated anyway due to automation and other factors.25

The approximately 400,000 manufacturing jobs lost [in the early 2000s] were the most during any decade since manufacturing employment peaked in 1969. This was due to three dominant factors: China’s accession to the WTO, automation, and the Great Recession.

Leaving aside the ongoing debate, three points regarding NAFTA’s effect on Ohio jobs deserve highlighting. First, manufacturing levels in Ohio remained constant through much of the 1990s (see Figure 4). Any significant number of Ohio manufacturing jobs lost due to the agreement appeared to have occurred from 1999 onward.26 Second, negative perceptions of NAFTA at least partially stem from concrete cases of key Ohio employers relocating production facilities to Mexico. For example, LG Displays, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, Delphi Corporation, and Honeywell International all moved production plants from Ohio to Mexico in the early 2000s.27 According to Department of Labor data on TAA petitions, the most significant layoffs in the 1990s and early 2000s occurred among auto, steel, and electronics manufacturers, including General Motors, Severstal Warren, and Huffy Bicycle, each idling over 1,000 Ohio workers.28 Finally, the total number of NAFTA-related job losses, while highly visible, were relatively small in comparison to those lost due to competition from China and other factors in the years 2000 to 2010.

More than 1 million Ohioans worked in the manufacturing sector at the beginning of 2000. That number dropped to just over 620,000 in 2010; the approximately 400,000 manufacturing jobs lost were the most during any decade since manufacturing employment peaked in 1969.29 This was due to three dominant factors: China’s accession to the WTO, automation, and the Great Recession.

No longer willing to risk being shut out of China’s rapidly growing markets as Asian and European competitors rushed in—and looking to promote and accelerate internal political and economic reforms through increased engagement in the new post–Cold War era—the United States formally extended Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) status to China in October 2000, paving the way for China’s accession to the WTO with U.S. support. This effectively ended a process begun in 1980 in which Congress annually reviewed whether to waive high tariffs on imported Chinese goods. Although Congress had authorized the waiver each year, it was never a foregone conclusion, especially after the massacre at Tiananmen Square in 1989. China’s PNTR status and formal accession to the WTO in 2001 created a new dynamic.30

After granting China the status, U.S. firms decided it was worth the sunk costs and risks to shift some production to China, where there were lower long-term labor costs.31 Simultaneously, Chinese producers decided they could afford to rapidly expand into U.S. markets. And upon recognizing that China was entering a phase of comparative advantage with reduced labor costs, U.S. firms then accelerated domestic investments in automation and other technological enhancements to better compete. This trifecta precipitated a major net reduction in U.S. manufacturing jobs, disproportionately borne by manufacturing states like Ohio. The losses considerably offset the export-related jobs created in the United States as a result of increased market access in China.

Considerable economic research in recent years has sought to quantify the net impact of Chinese import competition on U.S. jobs in the 2000s. One oft-cited study on the “employment sag” of the 2000s estimated that trade with China induced 985,000 manufacturing job losses in the United States between 1999 and 2011.32 However, this study was not a state-by-state analysis and did not estimate the losses applicable to Ohio alone. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) employed a different economic model to do such an analysis, concluding that trade with China cost Ohio 121,500 jobs from 2001 to 2015.33 But the EPI figures are contested by academic economists, who believe the number would likely be lower if based on the more widely accepted methodology.34

An equally important question yet to be resolved is how to reconcile the significant losses of one sector or constituency with the more modest yet important gains of others. During the 2000s, Ohio-based exports to China grew steadily in goods (for example, oilseeds and grains, aerospace products and parts, plastic products, and navigational and measurement instruments) and services (for example, education and travel), supporting thousands of higher-paying jobs in those sectors.35 Moreover, while increased trade with and investment in China displaced manufacturing jobs in Ohio, it also provided working families a wider selection of consumer goods at more affordable prices. Researchers at London’s Center for Economic Policy Research recently calculated that average prices paid for manufacturing goods by U.S. consumers were 7.6 percent lower between 2000 and 2006 (dropping 1 percent each year) due to China’s entry into the WTO.36 Still, this same drop in prices for American consumers is seen as the result of China’s currency manipulation, which suppressed the value of the renminbi during this period to make China’s imported goods more attractive.37

Just as the trade-related impacts varied considerably across industries in the 2000s, the same was true for the impact of automation and information technology. According to a recent study, between 2001 and 2010, automation, information processing, and other technological advances enabled triple-digit levels of growth in output and productivity in the computer and electronics sector.38 This also allowed for double-digit productivity growth in other industries, such as automobiles, chemical products, and primary metals. Almost 88 percent of all U.S. manufacturing jobs lost during the 2001–2010 study period was due to automation, not foreign trade. Although increased competition with Mexico and China—more than automation—accounted for the loss of lower skilled labor in the textiles, furniture, apparel, and paper industries, none of these industries were a large part of Ohio’s economy (except paper, which was also affected by the decline of printing and publishing). (Note, however, that some researchers believe the automation-related job losses are overstated, because they rely on methodology for calculating productivity gains, particularly in the computer industries, which they contest.39)

The major industries concentrated in Ohio are among those most exposed to automation and related job losses.

For manufacturing industries like those in Ohio, robotics is one of the main technologies that has displaced good-paying jobs.40 According to the Robotic Industries Association, the automotive industry is the primary driver of growth in robotics, with plastics and rubber, semiconductors, electronics, and metals also showing significant growth.41 Thus, the major industries concentrated in Ohio are among those most exposed to automation and related job losses.

Notwithstanding the ongoing robots versus trade debate, few economists dispute the devastating impact of the Great Recession on Ohio’s manufacturing industry. Even before it hit in December 2007, Ohio manufacturing job numbers had dropped from more than 1 million at the start of the decade to 772,000 (see Figure 4). Manufacturing employment levels plunged further to 621,000 by the end of the Great Recession in 2010. Recessions often hit the manufacturing sector harder than others, as evidenced by the loss of nearly 150,000 Ohio manufacturing jobs over just three years. But manufacturers have historically taken advantage of slowdowns to restructure and innovate, helping the sector to rebound, at least partially, in the post-recession period to a new equilibrium. The manufacturing job losses from the Great Recession, however, were especially deep and the recovery much shallower (see Figure 5).

Almost a decade later, Ohio’s manufacturing employment remains well below levels seen before the Great Recession due to the aforementioned combination of factors: industry restructuring, innovation, automation, offshoring, and import competition (including due to mercantilist practices).42 These factors permanently changed Ohio’s manufacturing sector, and no strategy will bring back all the lost manufacturing jobs—not even to the levels of the 1990s.

This new reality has hit all of Ohio hard but especially subregions that were heavily dependent on manufacturing industry clusters that suffered huge downturns between 2000 and 2016. These areas include Dayton, Toledo, Youngstown, Warren, and their surrounding areas, where the automotive industry is clustered; Stark (Canton) and Butler counties, as well as around Cleveland, where iron and steel mills are concentrated; and Summit County (Akron), where the tire and rubber industry is located. A number of rural counties were also devastated. For example, Monroe County in Appalachia lost 99 percent of its manufacturing workforce since 1990—half of which can be attributed to the closure of one aluminum company.43 Montgomery, Marion, Richland, and Trumbull counties, which all had per capita incomes near or exceeding the national average in 1970, had fallen well below the national average by 2015.44

The potential for large numbers of U.S. manufacturing job losses due to foreign trade was anticipated long ago. In fact, in 1953, at the height of the U.S. manufacturing sector’s dominance, David McDonald, then president of the United Steelworkers union, first floated the idea of TAA. As Edward Alden recounts in Failure to Adjust, McDonald was among the rare labor leaders who championed free trade. But he did so on the condition that free trade be paired with an ambitious government program to facilitate “adjustment” for American workers, industries, and communities that suffered as a result of more liberal trade policies that would yield net economic benefits for the nation as a whole.45 The precise nature of the adjustments have been the subject of intense debate ever since, often focused on income assistance and retraining for displaced workers and even tax breaks, technical assistance, and loans for adversely affected companies.46

In the 1960s, president John F. Kennedy was the first to introduce a TAA program as a way to shore up domestic political support for free trade on both sides of the aisle. He was determined to head off Soviet and Chinese attempts to undermine U.S. alliances in Europe and Asia and believed that increasing U.S. imports of allies’ goods would strengthen ties with them.47 Succeeding presidents from Nixon and Reagan to George W. Bush and Obama would come to view trade in similar terms—as one important component of binding like-minded allies together in the face of escalating geopolitical competition with adversaries and rising powers.

Successive administrations promoted trade liberalization over the next half-century, but trade adjustment assistance never kept pace and meaningful adjustment strategies for communities that lost their economic base never materialized. McDonald’s vision was never realized. What emerged was only a shadow of what he had in mind, as opposition to the program persisted across the political spectrum. In the 1960s, the levels of assistance turned out to be far less than envisaged, thereby creating buyer’s remorse for original trade skeptics who regretted having sold their support for free trade on the cheap. Nixon proposed a much more ambitious undertaking in the early 1970s, as part of his larger efforts to expand and overhaul unemployment insurance, but the proposal was largely rebuffed by business and labor alike, albeit for different reasons. Even the more modest version that Congress adopted, and which ended up helping more displaced workers, cost $4 billion in the 1970s.48 The high price tag provoked criticism of fiscal unsustainability and triggered substantial cuts during the Reagan era. Meanwhile, criticisms persisted regarding the inherent unfairness of the program. It provided support to foreign trade–displaced workers but not those displaced by domestic competition, automation, or changes in consumer preferences. And even with respect to the trade-displaced workers, the program was chastised for sustaining the unemployed rather than retraining them or helping businesses adjust to new economic realities, as originally promised.

Bush worked with Congress in the early 2000s to augment financing and improve eligibility criteria for TAA. Obama followed with more ambitious proposals for widening its scale and scope—some of which Congress adopted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. While Congress never took up Obama’s most ambitious proposals, such as extending TAA-like benefits to all displaced workers, including those displaced by automation, it did augment the program in its TAA Reauthorization Act of 2015 (which continues through 2021).49 Under this act, certified TAA benefits include reimbursement of training expenses; income support while in training after the expiration of unemployment compensation; reimbursement of job search and relocation expenses (up to $1,250); a healthcare coverage tax credit; and an income supplement for workers over fifty years old who secured reemployment at a lower wage (up to $10,000 maximum over two years).50

Successive administrations promoted trade liberalization over the next half-century, but trade adjustment assistance never kept pace and meaningful adjustment strategies for communities that lost their economic base never materialized.

Between 2000 and 2016, an estimated 133,000 workers in Ohio were certified as eligible to receive TAA benefits. Seventy-five percent of these workers were certified on the basis of increased imports or shifts in production to a foreign country.51 Even if eligible, not all participated.52 And for those who did receive TAA benefits, comprehensive data are hard to come by on what percent secured reemployment at an equal or higher wage after having lost a good-paying manufacturing job due to trade.

Those interviewed for this report almost uniformly expressed the perception that, over the past fifty years, TAA has meaningfully helped only a minority of trade-displaced workers in Ohio. In its recent incarnation, the benefits have helped to cushion the immediate blow of getting laid off and have subsidized some costs of transitioning to a new job. But, generally speaking, interviewees described new jobs that required similar skills as the old ones but with lower pay or new jobs requiring much less skill at much lower pay, often in a low-skilled service industry.53

The real challenge going forward is not to return the manufacturing sector to its previous levels of employment—that is no longer possible—but to restore a new social compact within Ohio’s new, more diversified economy.

Those interviewed also noted that the experiences of trade-displaced workers have varied considerably across the decades and in different firms—even within the same industries—due to the arrangements negotiated between labor and management. They viewed the lead time provided for layoffs, the company-provided support for reemployment, and the generosity of severance packages as considerably more important than TAA, especially for longtime employees.54 Labor representatives stressed that trade- and automation-related job displacements have been occurring since the 1950s. However, the trauma created by these dislocations has been more acute in recent decades, because workers in many companies have had less say over the transition arrangements. Labor representatives cited this as one relevant effect of the decline in private sector union density over the past fifty years.55 In the case of Ohio, the percentage of all nonagricultural unionized workers dropped from 37.2 percent in 1970 to 12.6 percent in 2017 (see Figure 6).

The above story is not just about the decline of employment in Ohio’s manufacturing sector and the failure to provide adequate adjustment assistance. It is about the impact on communities that lost their resource base and their identities. They did not have the ability to quickly reload their employment base, and they frequently lost the ability to invest in their future. The story is also about the unraveling of a social compact among business, labor, and government that once worked for the middle class—by spreading prosperity more equitably across the state, bringing dignity and status to families and communities, and building a solid nexus between skills training and jobs. The real challenge going forward is not to return the manufacturing sector to its previous levels of employment—that is no longer possible—but to restore a new social compact within Ohio’s new, more diversified economy.

1 William Shkurti and Fran Stewart, “The Decline of Ohio,” Toward a New Ohio paper series, John Glenn College of Public Affairs, 2018, http://glenn.osu.edu/toward-a-new-ohio/.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 1960 Census of Population, “Advanced Reports: General Population Characteristics,” March 28, 1961.

5 Shkurti and Stewart, “The Decline of Ohio.”

6 Lee E. Ohanian, “Competition and Decline of the Rust Belt,” Economic Policy Paper 14-6, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, December 2014, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/files/pubs/eppapers/14-6/epp_14-6_rev.pdf.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 For a brief but more detailed account of changes to U.S. international economic policy during this period, see “Nixon and the End of the Bretton Woods System, 1971–1973,” Office of the Historian, Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock. For a much fuller discussion, see Peter Peterson, “The United States in a Changing World Economy, Volume 1: A Foreign Economic Perspective,” December 27, 1971, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006243860.

10 In his remarks on “Oil and the Economy” delivered on October 21, 2004, then Federal Reserve Bank governor Ben Bernanke explained that “. . . during the 1970s and early 1980s, both the first-round and second-round effects of oil-price increases on inflation tended to be large, as firms freely passed rising energy costs on to consumers, and workers reacted to the surging cost of living by ratcheting up their wage demands. This situation made monetary policy making extremely difficult, because oil-price increases threatened to raise the overall inflation rate significantly. The Federal Reserve attempted to contain the inflationary effects of the oil-price shocks by engineering sharp increases in interest rates, actions which had the unfortunate side effect of sharply slowing growth and raising unemployment, as in the recessions that began in 1973 and 1981.” See https://www.federalreserve.gov/Boarddocs/Speeches/2004/20041021/default.htm.

11 Lee E. Ohanian, “Competition and Decline of the Rust Belt,” Economic Policy Paper 14-6, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, December 2014, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/files/pubs/eppapers/14-6/epp_14-6_rev.pdf.

12 David G. Taar, “The Steel Crisis in the United States and the European Community: Causes and Adjustments,” in Issues in U.S.-EC Trade Relations, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1988, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5960.pdf.

13 Douglas A. Irwin, Clashing Over Commerce (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 536.

14 David G. Taar, “The Steel Crisis in the United States and the European Community: Causes and Adjustments,” in Issues in U.S.-EC Trade Relations, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1988, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5960.pdf.

15 Ibid.

16 Robert Bruno, Steelworkers Alley: How Class Works in Youngstown (Cornell University Press, 1999), 9.

17 Bruno, Steelworkers Alley: How Class Works in Youngstown.

18 Tim Sablik, ”Recession of 1981–82,” Federal Reserve History, November 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/recession_of_1981_82.

19 “Sun Belt” was coined more than a decade earlier by Kevin Phillips in The New Republican Majority; see Anne Trubeck, “Why the Rust Belt Matters,” Belt Magazine, April 15, 2016, http://beltmag.com/why-rust-belt-matters/.

20 Shkurti and Stewart, “The Decline of Ohio.”

21 Ibid.

22 Recollection of the Carnegie task force members who served in former president William Clinton’s administration.

23 The Economic Policy Institute (EPI), which maintains strong ties to organized labor, produced estimates of total job loss in each state as a result of NAFTA, putting Ohio’s loss at 34,900 manufacturing jobs between 1994 and 2010; see Robert E. Scott, “The High Price of ‘Free Trade’: NAFTA’s Failure Has Cost the United States Jobs Across the Nation,” EPI, November 2003, https://www.epi.org/files/page/-/old/briefingpapers/147/epi_bp147.pdf.

However, Public Citizen, an advocacy group affiliated with Ralph Nader, estimated even higher NAFTA-related job losses than the EPI; see Global Trade Watch, NAFTA’s 20-Year Legacy and the Fate of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Public Citizen, 2014, http://www.citizen.org/documents/NAFTA-at-20.pdf. John McLaren and Shushanik Hakobyan demonstrated that the agreement’s overall impact on U.S. labor markets was very small or zero but that there were statistically significant negative impacts in specific industries and geographic locations. Relying on U.S. census data from 1990 and 2000, McLaren and Hakobyan illustrated how workers without a college degree were able to earn higher wages in certain manufacturing industries because they were protected from foreign competition through tariffs. After those tariffs on Mexican-made products, such as footwear, apparel, textiles and plastics, were lifted under NAFTA, however, U.S. firms had to reduce wages or lay off workers. These less-skilled, displaced workers did not have plentiful alternative employment opportunities, so they ended up having to take lower paying jobs, often in the service sector. In towns dominated by such previously protected industries, the glut of less-educated workers ended up depressing wages for all of them, including in the service sector. North Carolina and South Carolina were among the states most vulnerable to this effect, but Ohio suffered from this phenomenon, too, especially in a number of smaller cities and towns. See John McLaren and Shushanik Hakobyan, “Looking for Local Labor Market Effects of NAFTA,” Review of Economics and Statistics, October 2016, 98(4): 728–741, http://www.nber.org/papers/w16535.

24 “The Impact of Tariffs on the U.S. Auto Industry,” Testimony Before the United States Senate Committee on Finance, Submitted by Josh Nassar, United Auto Workers Legislative Director, September 26, 2018, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/26SEP2018NassarSMNT.pdf.

25 Peterson Institute for International Economics, “NAFTA 20 Years Later: Essays and Presentations at the Peterson Institute for International Economics Assessing the Record Two Decades After Approval of the North American Free Trade Agreement,” Briefing No. 14-3, November 2014, https://piie.com/publications/briefings/piieb14-3.pdf.

26 Policy Matters Ohio, “Trade Adjustment Assistance: New Opportunities for Ohio Workers,” May 18, 2009, https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/fair-economy/work-wages/trade-adjustment-assistance-new-opportunities-for-ohio-workers.

27 Ibid.

28 United States Department of Labor, Data on TAA Petitions and Determinations, accessed on April 30, 2018, https://www.doleta.gov/tradeact/taa-data/petitions-determinations-data/.

29 Shkurti and Stewart, “The Decline of Ohio.” Original data: U.S. Census Bureau, 1953–1989; Statistical Abstract of the United States, various years; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment in Non-Agricultural Establishments by Industry by State; Ohio Bureau of Labor Market Information, Current Employment Query, 1990–2016, http://ohiolmi.com/.

30 Justin R. Pierce and Peter K. Schott, “The Surprisingly Swift Decline of US Manufacturing Employment,” American Economic Review 106, no.7 (2016): 1632–1662, http://faculty.som.yale.edu/peterschott/files/research/papers/pierce_schott_pntr_2016.pdf.

31 Ibid.

32 Daron Acemoglu, David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, and Brendan Price, “Import Competition and the Great US Employment Sag of the 2000s,” Journal of Labor Economics 34, no. S1, Part 2 (2016): S141–S198. http://economics.mit.edu/files/9811.

33 Robert E. Scott, “Growth in U.S.–China Trade Deficit Between 2001 and 2015 Cost 3.4 Million Jobs,” Economic Policy Institute, January 31, 2017, https://www.epi.org/publication/growth-in-u-s-china-trade-deficit-between-2001-and-2015-cost-3-4-million-jobs-heres-how-to-rebalance-trade-and-rebuild-american-manufacturing/.

34 Author interview with Professor Ian Sheldon, trade economist, The Ohio State University, July 9, 2018.

35 “Ohio’s Exports to China,” State Report, The U.S.-China Business Council, 2018, https://www.uschina.org/sites/default/files/uscbc_ohio_state_report_2018.pdf.

36 Mary Amiti, Mi Dai, Robert Feenstra, and John Romalis, “How Did China’s WTO Entry Benefit U.S. Consumers?” National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w23487.

37 Eduardo Porter, “Trump Isn’t Wrong on China Currency Manipulation, Just Late,” New York Times, April 11, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/11/business/economy/trump-china-currency-manipulation-trade.html.

38 Michael J. Hicks and Srikant Deveraj, “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America,” June 2015, Ball State University, https://projects.cberdata.org/reports/MfgReality.pdf.