This paper is part of a series of four publications in a project run by the Carnegie Endowment’s Türkiye and the World Initiative, analyzing the forces at play in the Euro-Atlantic area since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. The project examines the European Union’s geopolitical evolution, Türkiye’s relations with Russia and China, and European and Turkish aspirations for strategic autonomy, and draws conclusions for the United States and the transatlantic partnership.

Introduction

Tense competition between the West and China in recent years has brought U.S. and EU policies toward Beijing into closer alignment. Although policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic acknowledge that there are areas in which they need to cooperate with China, such as on global health and climate change, their focus remains on managing competition responsibly by leveraging economic dependencies and de-risking their economies. This China-centered paradigm and geopolitical rivalry creates both challenges and possibilities for middle powers such as Türkiye seeking to derive strategic gains.

As a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member and EU-candidate country, Türkiye is an important transatlantic actor in Sino-Western competition. It can add value to Western efforts aimed at synchronizing policies toward a rising China. And yet, at present, Ankara’s policies on China are not harmonized with those of its partners in the West.

This paper examines Türkiye’s complex relationship with China, specifically outlining how this relationship manifests in Central Asia and Africa. It then draws conclusions about Türkiye’s potential contributions to transatlantic policies toward China and makes the following recommendations for U.S. and EU policymakers:

- Revitalize Türkiye’s economic integration with the West;

- Revise the Western approach to Central Asian connectivity; and

- Position Türkiye as a major partner in Western infrastructure development initiatives.

The Evolution of Türkiye’s Outlook on China

In political, economic, and security domains, Türkiye has been embedded in the Western institutional order and traditionally aligned itself with Western nations. However, as a more multipolar global order has emerged and Türkiye’s domestic political ideology has emphasized the country’s need for increased strategic autonomy, Turkish policymakers have reconceptualized the main tenets of the country’s international relations. Türkiye’s strategic engagement with China is a prime example of this transformation. It represents the country’s difficult balancing act between Western powers, such as the EU and the United States, and non-Western powers, such as China and Russia. It is also a function of the pragmatic and transactional approach that is at the heart of Ankara’s current foreign policy thinking.

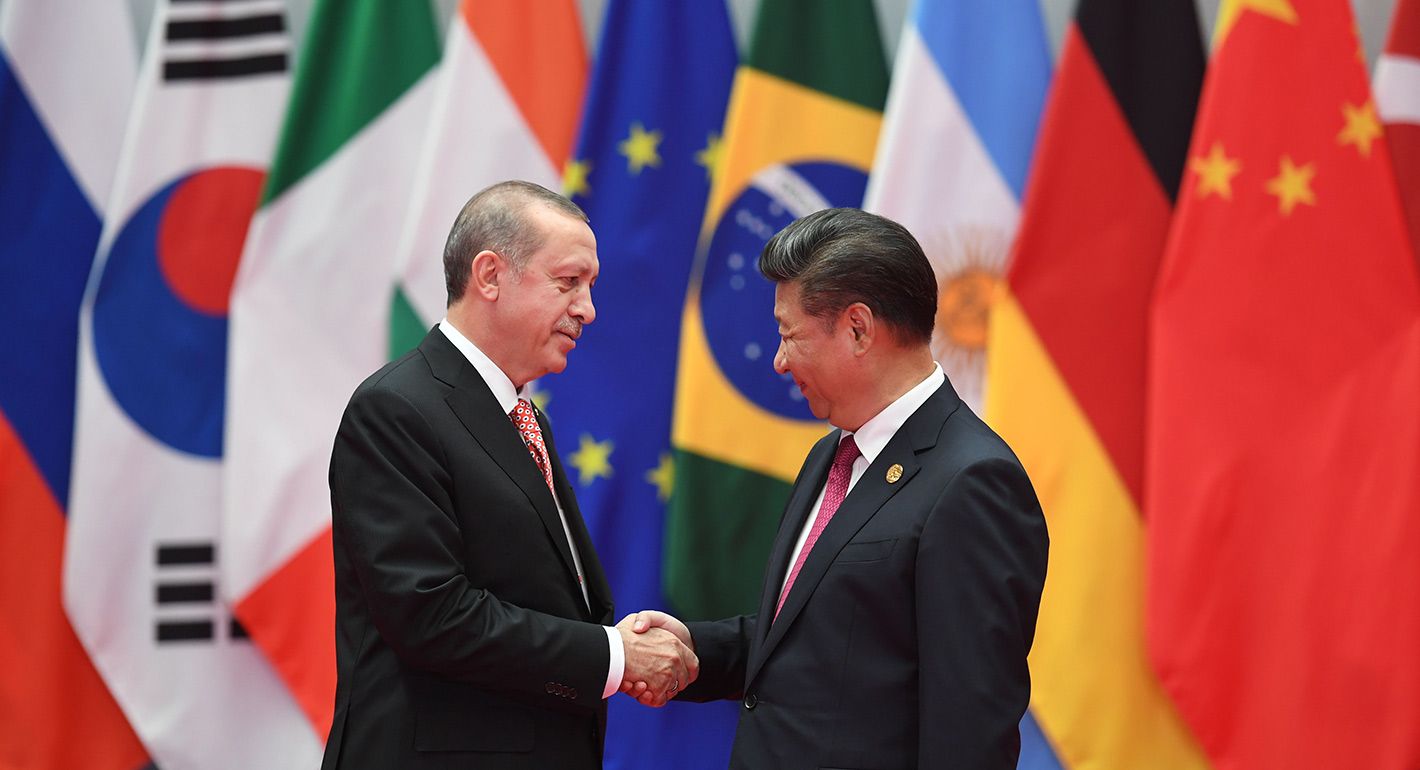

Türkiye’s bilateral relations with China were elevated to the level of “strategic cooperation” in 2010. Its careful cultivation of this relationship since then illustrates its commitment to maintaining strategic flexibility, thereby enhancing its role as a pivotal player in the evolving global order. China’s rise as an economic superpower and its role in regional initiatives like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) are additional factors that motivate Turkish policymakers. There is a strong expectation in Ankara that engagement with China will provide Türkiye with advantages and resources to accelerate its economic development.

In Ankara’s eyes, Beijing could provide increased financial commitments to the Turkish economy. Bilateral trade figures between the two countries are currently grossly in China’s favor: Türkiye imports $45 billion worth of Chinese goods and exports a mere $3.3 billion to China. The resulting trade gap of $41.7 billion is Türkiye’s largest bilateral deficit. Turkish policymakers also believe there is room for improvement in foreign direct investment (FDI) from China. Türkiye signed a Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) agreement with China in 2015, yet it ranks twenty-third out of eighty countries receiving Chinese investment. As of 2020, Türkiye had only received 1.31 percent of all investments made through the BRI. The Chinese stock of FDI in Türkiye reached $9 billion by end 2023, which is substantially low in relation to Western-origin FDI. Similarly, the number of companies with Chinese capital established in Türkiye since 2002 stands at 1,197, amounting to just 0.6 percent of all international companies in the country. Notably, Chinese FDI is higher in countries such as Malaysia, Pakistan, Israel, and Nigeria. Derya Göçer and Ceren Ergenç contend that the perceived erosion in rule of law standards and unpredictable policies in Türkiye has been a critical factor for lagging Chinese investments.

Ankara is also interested in advancing mutually beneficial cooperative schemes with Beijing. A case in point is the Middle Corridor land route, which links Türkiye to China through Central Asia, crossing Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which made the Northern Corridor trading route connecting China and Europe via Russia less attractive, Türkiye saw a window of opportunity for the Middle Corridor. Even though the transport time is roughly the same as maritime routes and not advantageous in that sense compared to the Northern Corridor, the World Bank projects trade volumes to triple by 2030 should better use be made of the Middle Corridor. This projection is based on the assumption that operational deficiencies at ports and choke points at border crossings can be overcome through the right investments. The World Bank also anticipates that the Middle Corridor will intensify regional trade and should have a similarly positive impact on trade between Türkiye and China.

Yet, despite so much potential and ample room for improvement on the economic front, there are other obstacles to any sustained and deep convergence between Türkiye and China. First, and most importantly, the treatment of ethnic minorities in China is a source of great dissonance. Türkiye is home to the world’s largest Uyghur diaspora, who are ethnically related to the Turks. The issue reached a tipping point in 2009 after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called China’s treatment of Uyghurs “almost a genocide,” and it remains a point of serious tension.

Second, Ankara and Beijing are locked in an increasingly palpable geopolitical competition in places such as Africa and Central Asia. This is a real counterforce to the gravitation between Türkiye and China. Therefore, examining their unspoken rivalry in such geographies is a good starting point to better understand this complex relationship’s true dynamics.

Economic and Geopolitical Influence in Africa

Africa has significant economic growth potential, driven by its natural resources and increasing urbanization. Both China and Türkiye view the continent as a key market for their goods and services and a source of critical natural resources. Consequently, they have both emerged as major actors in Africa, pursuing their own economic and strategic interests that occasionally collide.

Increased Engagement in Africa

China’s engagement in Africa significantly increased after 2000, fueled by a wave of large infrastructure investments, as illustrated by the proliferation of BRI projects across Africa and Beijing’s lead role in facilitating connectivity projects across the continent. Over the past twenty years, China has become sub-Saharan Africa’s largest bilateral trading partner. According to the International Monetary Fund, around 20 percent of the region’s exports now go to China and about 16 percent of its imports come from China. The volume of trade surpassed the threshold of $280 billion in 2023. In recent years, China has also become the top investor in Africa, focusing particularly on infrastructure projects such as railways, roads, and ports. These investments have several motives, including accessing the continent’s resources, expanding the market, gaining strategic influence, providing economic aid, and boosting the BRI.

Türkiye’s engagement with Africa also increased after the 2000s, as it sought to diversify its foreign policy and find new markets for its booming manufacturing capacity. Türkiye declared 2005 as “The Year of Africa” and followed this with other politically symbolic steps, such as launching the Turkish-African summit in 2008, similar to China’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), thereby institutionalizing its engagement with the continent at the highest level. In parallel, Ankara’s diplomatic footprint in Africa expanded considerably. There are now forty-four Turkish embassies in Africa, compared to twelve in 2002. Ankara also launched cultural programs, business councils, and an extensive connectivity network across the continent, with government-linked Turkish Airlines now flying to more than sixty African destinations. In the meantime, Türkiye’s investments in Africa diversified and now span sectors ranging from construction to energy and agriculture.

Strategic Goals and Intentions

Türkiye and China both pursue multifaceted approaches in Africa aimed at building goodwill and strengthening diplomatic ties. They similarly attribute a significant role to soft power in their strategic engagement, presenting themselves as attractive alternatives to traditional Western donors. Both try to distinguish themselves from the West by rejecting conditions-based cooperation models that African leaders complain are intrusive or paternalistic. As a corollary to this narrative, they both highlight differences in their historical legacies with the continent from those of Western colonial powers.

There are also fundamental differences in the two countries’ approaches toward Africa, including in the weight they place on achieving political as opposed to economic objectives. Compared to Türkiye, China’s engagement with African countries is more driven by political neo-mercantilism. Although China’s approach is often presented under the banner of noninterference in countries’ internal affairs, there are strong concerns about the true intentions behind its large-scale investment programs.

In the past two decades, China has been the largest lender in Africa, granting forty-nine African nations and regional organizations loans exceeding $170 billion. At the same time, China’s financing model for infrastructure investments has resulted in substantial debt burdens for many African countries, leading to economic instability. This massive influx of Chinese capital has generated questions over whether China may be pursuing a so-called debt-trap policy, wherein countries become so indebted that they are forced to cede control over key assets and make policy concessions to Beijing. This has sparked widespread concerns about the long-term implications of these financial arrangements and the political leverage China accrues from them.

The primacy of political considerations is also visible in Beijing’s promotion of its enterprises. It aims to secure access to Africa’s raw materials and natural resources that are integral to the continued growth of China’s manufacturing industries. Chinese companies have heavily invested in African mining operations, oil fields, and agricultural projects, ensuring a steady flow of raw materials. This supply chain integration allows China to maintain competitive manufacturing costs and support its extensive infrastructure development projects both domestically and internationally under the BRI.

In contrast to China, Türkiye’s economic engagement with African countries is driven by a mix of motivations. Türkiye’s and China’s competitive advantages and differences in how state-capital relations are structured come into play. Türkiye has very limited fiscal capacity to leverage. As a result, its engagement is driven more by development aid programs that are framed as partnerships of mutual benefit, rather than as instruments to exert influence or control. This aligns well with the aspirations of many African leaders who prefer development assistance that supports their national agendas without external interference.

Second, unlike China’s, Türkiye’s economic engagement is driven by market fundamentals. This is a function of the disparities in the two countries’ political economies. China’s state capitalism model informs a different engagement strategy where economic objectives can take second place to broader political aims. In Türkiye, this type of dirigisme is much less prevalent. Turkish enterprises in Africa are essentially profit-seeking entities that may rely on the support of the Turkish political leadership to earn more favorable treatment in the African market, but, in general, their motivation remains driven by market fundamentals and opportunities.

Türkiye’s economic footprint in Africa is visible, particularly in the extractive industries and the construction sector. Turkish enterprises are involved in resource extraction and energy projects in several African countries, where they have invested in oil exploration and renewable energy initiatives. Over the years, Turkish companies have also successfully leveraged their competitive advantage in large-scale infrastructure projects by expanding their regional footprint. By 2023, the portfolio of construction projects entrusted to Turkish companies in Africa had reached $85 billion. The size of this portfolio placed Türkiye second after China in Africa’s infrastructure development. Some notable examples include the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway in Ethiopia, Africa’s largest financial center development project in Kinshasa, the fast train project that will link Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, renewable energy projects in Senegal and Mali, seaports in Somalia, and airport construction and operation in Libya, Senegal, and Sudan.

Türkiye’s economic and political involvement in Africa has incidentally helped bolster the country’s economy. By fostering strong trade and diplomatic relations, Türkiye has successfully encouraged business communities in several African nations, such as Somalia, to import goods like textile products and pharmaceuticals from Türkiye. This has not only strengthened bilateral ties but also facilitated mutually beneficial economic partnerships. These engagements have generated positive economic outcomes for Türkiye, enhancing its export markets and supporting domestic industries, while simultaneously contributing to the development and diversification of African economies.

Another key factor that has played a significant role in shaping Ankara’s approach to Africa has been its growing security and defense footprint. Türkiye’s diplomatic engagement has been traditionally more focused on Northern Africa. This focus started to widen with the country playing a vital role in Somalia by delivering aid during a devastating famine in 2011. This humanitarian engagement was complemented by a security and defense partnership with Somalia, which in 2017 saw the establishment of Türkiye’s largest overseas military training facility, Camp TURKSOM in Mogadishu. Türkiye has concluded security agreements with thirty African countries including Algeria, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, and Tunisia. These military framework agreements cover training, technical collaboration, and scientific cooperation. They may also include provisions around arms sales. Indeed, over the past decade, Türkiye has become a more visible supplier of defense products to African nations and, as such, has emerged as an alternative supplier to China. This is particularly true for some key platforms, such as armed drones, where the Turkish supply has generated considerable interest. In the ongoing competition against Chinese military platforms in Africa, Turkish drone exports benefit from Türkiye being a NATO nation and, therefore, its defense industry production being in compliance with NATO standards. But compared to other NATO nations like the United States and the United Kingdom, Türkiye has adopted a less onerous framework for greenlighting drone exports. As a result, “a mutually reinforcing policy design of arms exports, military training, and defense diplomacy allows the Turkish administration to build long-term and institutional bonds with African countries,” according to the Centre for Applied Turkish Studies’ fellow Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar.

Rising Competition in Central Asia

Traditionally, Central Asia—namely Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—has been perceived as a region where the only external powers to hold significant influence are Russia and China. Unlike Russia, which inherited its influence in the region following the collapse of the Soviet Union, other countries—including China and Türkiye—had to reestablish their presence after a century without any direct ties with Central Asia.

In the early 1990s, both Beijing and Ankara sought to expand their influence in Central Asia, albeit for different reasons. For China, the primary concern was national security. Central Asia borders the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which Beijing perceives as a potential source of instability. China sought to institutionalize its presence in Central Asia not only through bilateral engagements but also via multilateral frameworks. In 1996, China collaborated with Russia to establish the Shanghai Five organization, which initially aimed to delineate new borders between China and the former Soviet states. This organization later evolved into the SCO.

Like Beijing, Ankara also sought to capitalize on the collapse of the Soviet Union and expand its influence in Central Asia. When the five Central Asian nations emerged as independent entities three decades ago, Türkiye was among the first to establish official diplomatic relations with the region’s Turkic-speaking nations. In the 1990s, Central Asian leaders viewed Ankara as a potential partner for counterbalancing against Russia. Their strategic alignment was driven by the desire to diversify their foreign relations and reduce overreliance on Moscow. Türkiye’s shared cultural and linguistic ties with the Turkic-speaking nations of Central Asia further facilitated this partnership, fostering a sense of brotherhood and mutual support.

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were the most enthusiastic about strengthening ties with Türkiye. Uzbekistan’s then president Islam Karimov declared, “My country will follow the Turkish path, and we will not deviate from it.” Both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan initiated language reforms, adopting a Latin alphabet similar to the Turkish version. In contrast, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan continued to rely more heavily on Russia than on their neighbors. Tajikistan, as the only non-Turkic country in Central Asia, also did not engage as closely with Ankara. Nevertheless, Türkiye did not entirely overlook Dushanbe, maintaining a degree of diplomatic, economic, and cultural interaction.

However, Central Asia’s initially warm relationship with Türkiye began to deteriorate in the 2000s. Türkiye had envisioned itself as the leader of the Turkic world, ambitiously proclaiming a sphere of influence “from the Adriatic Sea to the Great Wall of China.” Central Asian leaders grew suspicious and were irritated by what they perceived as Ankara’s patronizing approach. They also reacted negatively to the pan-Turkic and Sufi-Islamist ideology propagated by the Gülen schools. Tashkent was the first to shut down the schools, even sentencing some of the graduates and administrators.

Türkiye’s Comeback

Türkiye’s approach in the last years is markedly different to that of the 1990s. During meetings with Central Asian leaders, Erdoğan now emphasizes themes of brotherhood and mutual respect. Ankara presents itself as an attractive and trusted ally. The geopolitical landscape around Eurasia has also shifted significantly. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has undoubtedly motivated Central Asian states to diversify their ties beyond Russia and China.

Ankara’s ambitions in Central Asia are not just symbolic: Türkiye has a tangible presence in the economic, political, security, and cultural spheres. This multifaceted engagement underscores Türkiye’s commitment to strengthening its influence and fostering deeper connections with the Central Asian nations.

Türkiye ranks among the top four trade partners of all Central Asian states. As of 2023, Ankara’s trade volume with the region’s countries reached nearly $13 billion, a tenfold increase from a decade ago. Additionally, Türkiye is among the top ten investors in Central Asian economies, with a collective investment portfolio of around $10 billion. More than 4,000 Turkish companies operate in the region, making Türkiye one of the most prominent foreign business presences, third after Russia and China.

Türkiye also has a significant presence in the sensitive sphere of regional security, a trend that was previously not visible. Türkiye is the largest exporter of arms to Turkmenistan, the second largest to Kyrgyzstan, the sixth largest to Uzbekistan, and among the top ten arms exporters to Kazakhstan, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Recently, Türkiye has exported military drones to Kyrgyzstan, which deployed them on the battlefield during its latest clash with Tajikistan. Moreover, during Erdoğan’s state visit to Kazakhstan in 2022, the two countries signed a protocol on cooperation in military intelligence.

Connectivity represents another significant area of opportunity for Türkiye. All Central Asian countries are landlocked, surrounded by economically and politically isolated nations such as Iran and Afghanistan. Without direct access to international ports and markets, these countries rely heavily on trade routes over land. Western sanctions on Russia have exacerbated the logistical challenges in the region, despite infrastructure investments by China since 1991. The region remains dependent on Soviet-era trade routes. The 40 percent drop in China-EU shipments through the Northern Corridor and rising global freight costs have renewed interest in enhancing connectivity via the Middle Corridor. This route, bolstered by projects like the Trans-Kazakhstan Railroad and Baku-Tbilisi-Kars Railway, is becoming a viable alternative. Türkiye is actively leading initiatives to address the current logistical problems of the Middle Corridor and create an integrated rail and shipping network.

Türkiye’s regional resurgence is symbolically marked by the transformation of the Turkic Council into the Organization of Turkic States (OTS), which is emerging as a significant platform for Türkiye’s growing influence in the region. This rebranding was accompanied by the group’s evolution from a loose partnership to a full-fledged organization. OTS has become a key platform for economic and cross-sectoral cooperation for Turkic states. It brings together heads of state, ministers, and private sector leaders to foster collaboration in areas such as transport, energy, and trade through various mechanisms, including the Turkic Business Council and the Turkic Chamber of Commerce and Industry. These mechanisms facilitate joint projects and cooperation between Central Asian countries and Türkiye, making OTS a vital mechanism for economic collaboration in the region. During the tenth OTS summit in Kazakhstan, the member states signed the “Turkic World Vision 2040,” which outlines the organization’s priorities. According to that document, the member states will enhance their cooperation in various areas, including politics, transport, customs, and energy.

A key aspect of Türkiye’s soft power is education, including scholarships, exchange programs, and the establishment of universities like Manas University in Kyrgyzstan and Ahmet Yesevi University in Kazakhstan. These efforts aim to strengthen long-term ties and educate future political elites. Additionally, the Yunus Emre Institute and the Turkish Maarif Foundation play important roles in Türkiye’s current policies toward Central Asia. Ankara’s soft power initiatives in the region seem to have positively contributed to Türkiye’s overall perception. According to the Central Asia Barometer’s 2023 report, Türkiye is the best-regarded foreign country in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan and the second best-regarded (after Russia) in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Conversely, Russia’s reputation has steadily declined since the onset of its war against Ukraine. Its approval rating in Kazakhstan fell from 55 percent in 2021 to 29 percent in 2022, marking a historic low.

While Türkiye’s influence in Central Asia remains limited compared with Russia and China, Ankara holds a strategic advantage for the future. Türkiye can leverage its historical ties to advance its heritage diplomacy without confining Central Asia to its imperial near abroad or inciting fears of a loss of sovereignty across the border.

Onboarding Türkiye on Transatlantic China Policies

In the current geopolitical context, Turkish policymakers are more interested in deepening the country’s relations with China than being part of the Western-led policy of de-risking or even de-coupling from Beijing. Erdoğan’s continued interest in Türkiye’s potential membership in BRICS and the SCO is a testimony to this proclivity. This outlook is motivated by the perception that Türkiye can profit economically and possibly politically from a more comprehensive associational arrangement with China when the opportunities for constructive engagement with the West have stalled. This is partly due to the overriding difficulties in Türkiye’s relationship with the West because of its departures from adopted norms on democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. But it is also due to policy failures in the Western capitals that have tended to create obstacles to a realistic path of engagement with Ankara in spite of this democratic backsliding.

Yet onboarding Türkiye on a transatlantic China policy remains important as Ankara could provide significant contributions to the West’s rebalancing away from China, especially in Africa and Central Asia, where transatlantic partners’ engagement is vulnerable because of historical grievances or cultural cleavages. Also, with its industrial know-how and reserves of certain critical raw materials, Türkiye could enhance Western economies’ resilience as they attempt to de-link or de-risk from China.

In reality, Türkiye’s stance on China will only change if the prospects and incentives associated with closer alignment with the West are altered. Viewed from that perspective, the following policy recommendations can inform transatlantic leaders as they attempt to onboard Türkiye.

Revitalize Türkiye’s Economic Integration with the West

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has stated that a key justification for Ankara’s desire to join BRICS is its stalled bid to modernize its existing trade arrangement with the EU. Türkiye and the EU have a customs union that dates back to 1995. The agreement is thirty years old and in dire need of an overhaul. Despite the high priority attached to this objective by Ankara, European governments have been unable—since 2016 when the European Commission tabled its request for a mandate for negotiations—to greenlight this initiative on account of political considerations. This lack of progress has provoked a real sense of alienation in Ankara, especially since the EU has started to make political openings to new enlargement countries with a view to accelerate their membership dynamics. Turkish policymakers see the EU’s position as a sign of insincerity and strategic myopia since it amounts to blocking every meaningful channel of potential cooperation with Ankara, with the exception of the March 2016 refugees deal.

To reshape Türkiye’s political and economic calculus with China, the EU should review its long-standing opposition to starting negotiations on the modernization of the EU-Türkiye Customs Union. In its absence, the West will lack the credibility to nudge Ankara to deepen economic integration with the transatlantic community.

Revise the Western Approach to Central Asian Connectivity

Transatlantic partners are currently on a collision course with Türkiye on the issue of connectivity in Central Asia. In contrast to the Middle Corridor project championed by Türkiye, which aims to improve connectivity between Central Asian countries, Türkiye, and China, the EU and the United States have officially backed a logistical route linking India to Europe and bypassing Türkiye. This exclusionary approach undermines efforts to bring Türkiye into closer alignment with the transatlantic China policy. Western partners may view the project championed by Ankara as an enabler for China’s trade ties and economic footprint. But, in reality, the project can equally serve to lower Central Asian countries’ trade dependence on China given their increased connectivity with Western markets through Türkiye. In other words, Türkiye’s push for the Middle Corridor and a closer integration with the OTS could lead to regional stabilization and closer integration of Central Asian and South Caucasian states. This could in turn supplant Russia’s fading influence and balance China’s rising influence in the region. This dynamic is critical in Sino-Western economic competition.

At the very least, Türkiye and the transatlantic partners should avoid the spectacle of zealously championing competing projects for the region’s future connectivity. This shortcoming speaks to the lack of a proper and mature bilateral format of comprehensive deliberations between Türkiye and its main diplomatic partners in the West on the future of relations with China. This objective has been hindered by the total collapse of Türkiye-EU foreign policy alignment as a sign of increased mutual frustrations.

Position Türkiye as a Major Partner in Western Infrastructure Development Initiatives

Another valuable incentive for enhancing Ankara’s stronger alignment with the transatlantic China policy is Türkiye’s stronger embedding in the multilateral infrastructure programs launched by the transatlantic partners. The EU’s Global Gateway program aims to boost smart, clean, and secure connections in the digital, energy, and transport sectors and strengthen health, education, and research systems worldwide. The program, which is to benefit from 300 billion euros mobilized over the 2021–2027 period, can be seen as an innovative global infrastructure development program. Across the Atlantic, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) represents the US-led flagship multilateral infrastructure initiative. PGII aims to address the demand for high-quality infrastructure financing in low- and middle-income countries. More effective and inclusive partnership mechanics open to Türkiye’s involvement would create the right conditions for significantly improved levels of participation by Turkish economic actors. They could support global efforts to mobilize investments in infrastructure-related public works where Turkish companies have a competitive advantage and strong track record, which would, in turn, enhance regional economic development.

Conclusion

For these recommendations to have policy implications—and for any strategy that intends to align Türkiye more closely with a transatlantic strategy on China—there needs to be political will in Washington and in European capitals to achieve this goal. Likewise, Türkiye’s political leaders should also be willing to reappraise their current policy of balancing between Türkiye’s traditional partners in the West and the non-Western powers like China and Russia.

It will undoubtedly be difficult to establish a common understanding as long as Ankara keeps pushing for and lauding the benefits of Türkiye’s participation in regional cooperation initiatives influenced by Russia and China’s political ambitions, such as the SCO and BRICS. The pretense that there would be no political cost attached to Türkiye’s membership in these organizations in terms of its overall relationships with EU countries and the United States is just that—a pretense. In reality, this outreach greatly complicates Türkiye’s perception as a solidary member of the transatlantic alliance. And, by the same token, it generates the underpinnings of today’s volatile equilibrium in terms of Ankara’s relations with the West.

With sustained hesitancy about Ankara’s true proclivities, Western capitals are less eager to allocate political capital to develop a more inclusive policy toward Türkiye. The more this lack of appetite becomes visible, the more Ankara feels reassured that its openings toward China and Russia are justified. Viewed under this lens, the geopolitical imperative of designing an architecture of convergence with Türkiye on China can possibly create the needed momentum and mutual political will to break this volatile equilibrium.