A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

Because strategic, economic, and ideological perceptions of China contain multiple, sometimes contradictory facets in Southeast Asia, receptions of and responses to Beijing diverge across and within state lines.

Carnegie China has a long history of operations in Beijing. But over the past year, we have shifted our operating model to become a China-focused center anchored in East Asia more broadly, not just on the Chinese mainland.

By basing Carnegie China’s office operations in Singapore, our center has new reach in Southeast Asia even as we continue a full suite of activities with a range of Chinese institutional partners.

In this new incarnation, Carnegie China will be an East Asia–based research center focused on China’s regional and global role—anchored in the wider region and engaging a wide swath of Asian voices.

To make a running start on this broadened mandate, we have brought onboard several leading Southeast Asian scholars, including some of the region’s leading experts on Chinese policy and strategy. We are also launching new branded research products and analytical series, including the workstream that is reflected in this Carnegie China compendium on China Through a Southeast Asian Lens.

The revamped center will continue to be active in, on, and with Chinese stakeholders and institutional partners. For instance, we maintain a robust suite of track 2 policy dialogues with leading Chinese research centers in both Beijing and Shanghai. But with our broadened mandate anchored in the wider East Asian region, we aim to cast a critical eye on China’s strategic and economic trajectory and look not just to harness Chinese perspectives from the inside out but regional perspectives on China from the outside in. And from its new base of office operations in Singapore, the center aims to highlight Southeast Asian perspectives especially.

This is important for several reasons. For one, intensifying strategic competition between the United States and China risks crowding out local perspectives, forcing a false choice onto Southeast Asian governments, firms, and people. The reality is that nearly everyone in the region prefers addition and multiplication to subtraction and division. While Washington and Beijing seem to believe that Southeast Asians should focus on their agenda of competition with one another, the dominant dynamic in the region itself has been to leverage America and China to serve Southeast Asians’ own aspirations for growth, employment, upskilling, and sustainability.

We aim to understand the implications of these local dynamics, even as we continue to address the big strategic and international security questions that will shape Asia’s future with a more powerful and assertive China.

This compendium focuses on China and Southeast Asia from the perspective of each side. One section examines how Southeast Asia’s many new governments of the past few years may or may not look at China differently from their predecessors. Another turns the focus back to Beijing by asking how effective Chinese diplomacy under President Xi Jinping has been in this diverse and multifaceted region. A final section considers China’s much-vaunted Belt and Road Initiative, which has delivered mixed returns and complex stories across Southeast Asia.

This compendium is emblematic of our exciting new buildout under the center’s dynamic new model.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Vice President for Studies, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Acting Director, Carnegie China

Chong Ja Ian and Elina Noor

Contemporary relations between Southeast Asian states and the People’s Republic of China reflect an intricate mix of interests, actors, perceptions, and lived experiences. This complexity may seem obvious given China’s sheer size and the variance in political systems, economic models, historical traditions, and cultural diversity found in Southeast Asia. Yet too many analyses of the relationship focus on just one of these three explanatory aspects: ideological alignments, economic opportunism by one or the other side, or relative strategic acumen. Single-issue headlines around, say, the South China Sea dispute also tend to overshadow the diversity of the region’s individual and collective approaches toward China.

There is, therefore, a proclivity to imagine a spectrum in Southeast Asian states’ relations with Beijing and Chinese actors. Cambodia and Laos are often viewed as being “closest” to China in policy alignment and political preference, with the Philippines being at the opposite end, and the rest of the region’s countries falling somewhere in between. While this spectrum may be useful, it’s important to consider that perspectives, postures, and positions across Southeast Asian states are as diverse as the region itself. Some differences can even cut across national and societal lines within each country.

Many Southeast Asians view China as a significant economicpartner given its market size and expectations of forthcoming investment. Even the Philippines, which terminated three of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and advanced multiple fronts of defense cooperation with the United States and others since Ferdinand Marcos Jr., became president in 2022, remains open to Chinese trade and investment.

This growth-driven outlook emphasizes the large figures associated with Beijing’s infrastructure investments—notably, through the BRI—and that China is each Southeast Asian state’s largest trading partner in goods. Beijing shows consistent interest in participating in the region’s many economic frameworks, from the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. It is even seeking membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, which includes several major Southeast Asian economies, such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam. Southeast Asia’s economic future, from this perspective, lies in accommodating Beijing.

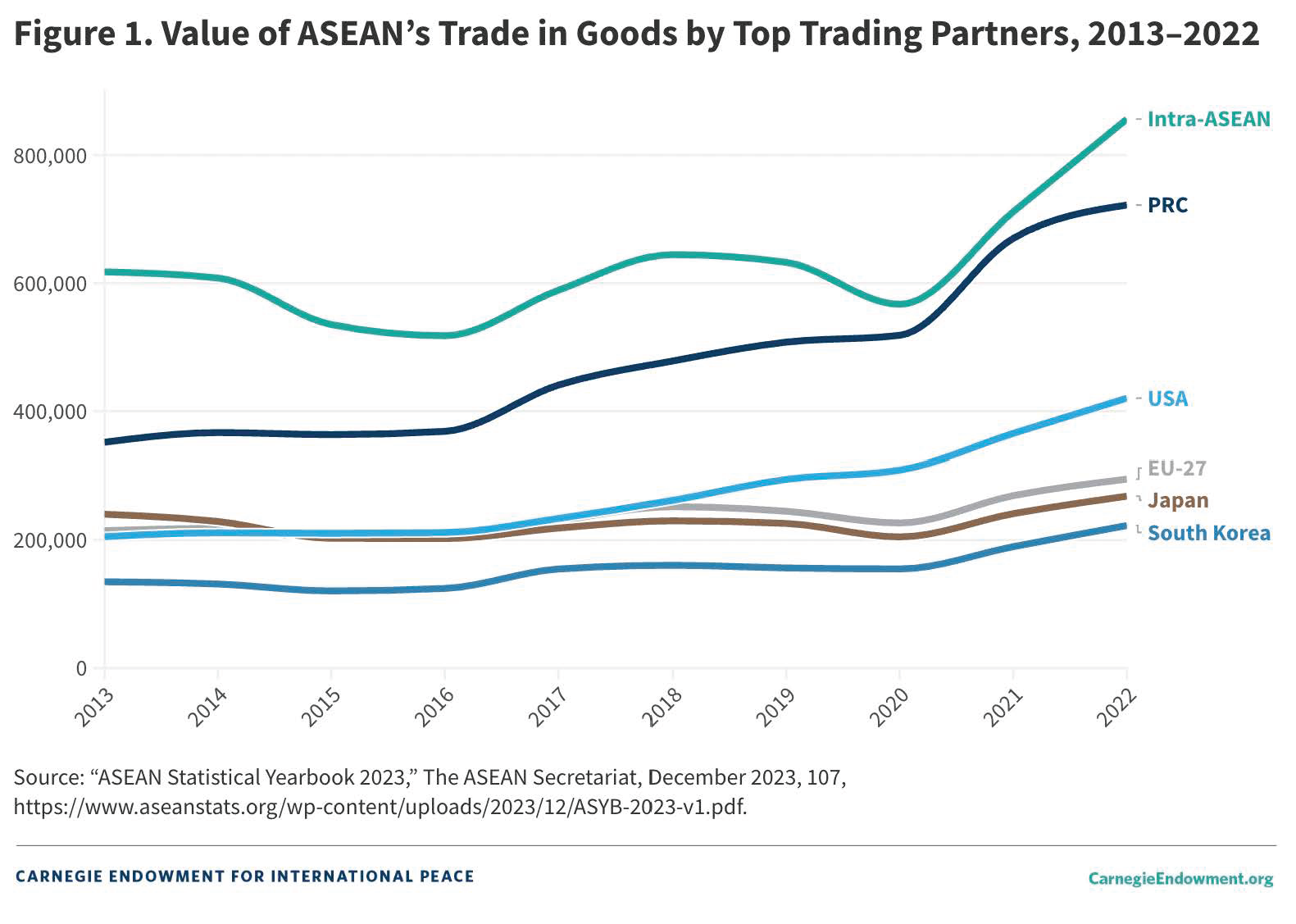

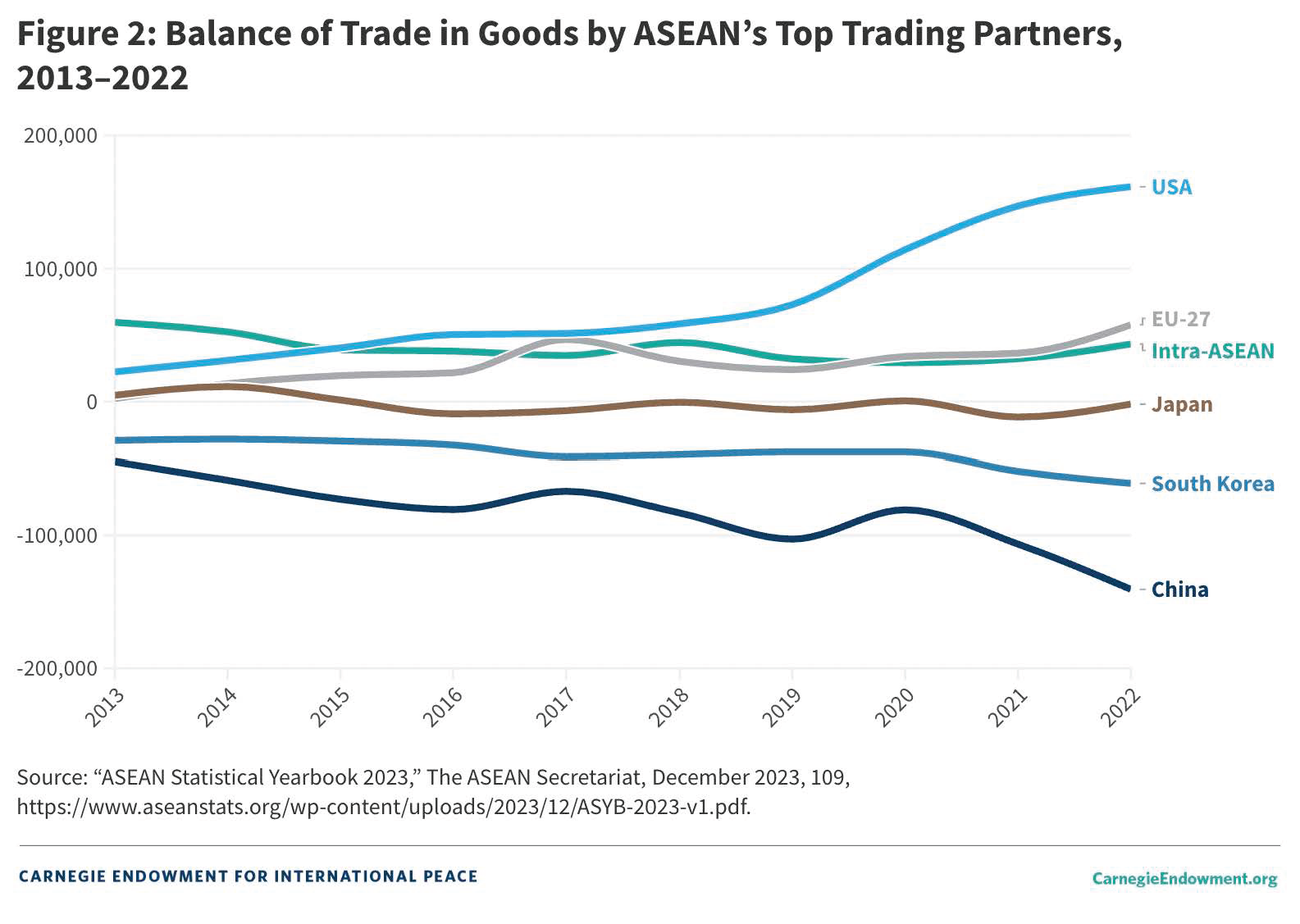

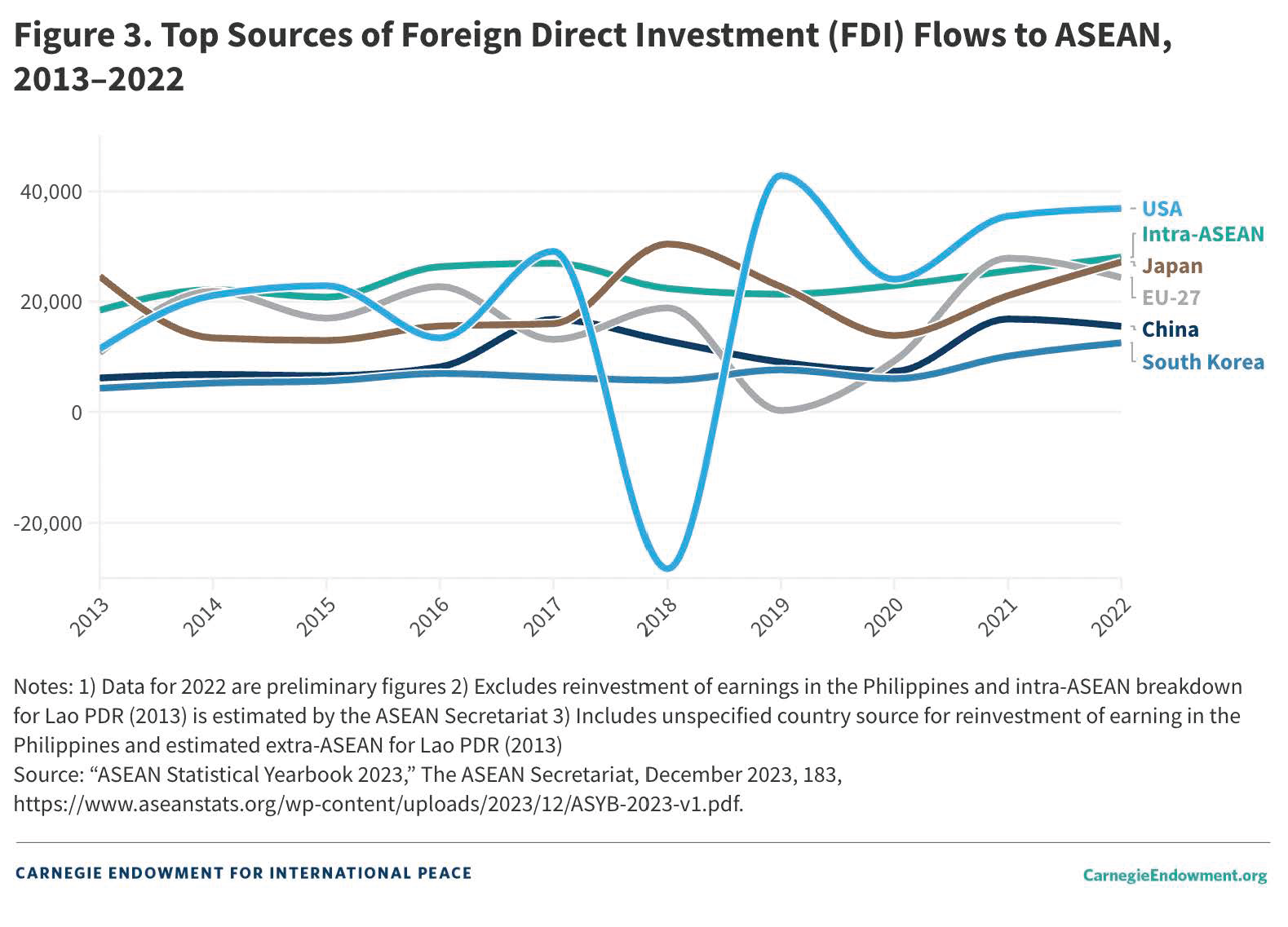

But these interpretations understate the reality that Chinese foreign direct investment in the region persistently lags behind investment from the European Union, the United States, and Japan (see Figure 3), based on official ASEAN Secretariat reporting. Even though China is the largest bilateral trading partner in goods for all ASEAN states, the region runs a chronic trade deficit with China (see Figures 1 and 2), again according to ASEAN’s own data. In essence, regional states tend to use capital from various parts of the world to purchase and assemble components from China for further export to final markets elsewhere. Common interpretations have also overlooked how China’s still-maturing economy and demographic decline will impact bilateral ties in uncertain ways.

Penned by a group of regional scholars that represent nearly every country in Southeast Asia, this Carnegie China compendium considers a diverse spectrum of opinion on the issues listed above.

Beyond economic considerations, for example, countries remain ambivalent toward China’s long-term ambitions. Beijing and its vision of its own “great rejuvenation,” as President Xi Jinping puts it, offer a way to fend off “Western” and especially U.S. pressure. Southeast Asia contains a reservoir of “anti-Western,” anti-American sentiment borne from the excesses and abuses of colonialism, the Cold War, especially, in localities with large Muslim populations, which is tied to some of the excesses associated with the global war on terror, such as Islamophobia. The current crisis in the Middle East has entrenched these views in some places, especially in Indonesia and Malaysia; in these two countries, impressions of unequivocal and long-standing U.S. support for Israel—particularly since Tel Aviv’s military operation in Gaza to punish Hamas for the October 7, 2023, attacks in southern Israel—starkly contrasts with Beijing’s condemnation of Israel and its mediation among Palestinian factions.

Meanwhile, others—especially Southeast Asian elites—see continued active engagement by the United States and other major powers as a crucial means of diluting Beijing’s excessive sway in the region. But this also means that frustrations about specific elements of American foreign policy, perceptions of U.S. hypocrisy, and Washington’s inconsistent commitment and unwillingness to grant market access that many Southeast Asian elites associate with the United States, can dampen ties. Such considerations sometimes encourage Southeast Asian elites to search for other partners.

Of course, like Washington, Beijing also has baggage that does not sit easily with Southeast Asian nations. Beijing has been complicit in bloody insurgencies, revolutionary regimes, and attacks on ethnic Chinese populations in Southeast Asia, such as during the Cold War. More recently, ethno-nationalist perspectives from Beijing that seek to mobilize Southeast Asia’s large ethnic Chinese populations in support of its “Chinese dream” of nationalrejuvenation have revived discomfiting shadows of the not-so-distant past.

Southeast Asian states have spent their post-independence decades trying to incorporate local ethnic Chinese communities, with varying degrees of success. Ethnic sensitivities remain fraught, ripe for exploitation in countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, which experienced violent racial riots only a few decades ago. Any perceived attempt by Beijing to interfere, much less intervene, in this aspect of Southeast Asia’s domestic affairs triggers alarm bells for regional leaders.

There is also uneasiness about a return to a past that saw Sinitic empires impose subordinate, tributary positions on Southeast Asian polities, although there are some who may actually welcome such a future. Complicating matters further are anxieties among maritime Southeast Asian states about Beijing’s efforts to seize, control, and militarize disputed South China Sea features regardless of prevailing understandings of international law. Mainland Southeast Asian states worry that upstream Chinese-built dams enable Beijing to affect the flow of major rivers in ways that can disrupt livelihoods and economies downstream. Beijing has a recent history of getting specific ASEAN members to withhold their agreement to prevent the grouping from attaining the consensus necessary to develop a common position on key issues such as managing the South China Sea dispute.

Because strategic, economic, and ideological perceptions of China contain multiple, sometimes contradictory facets in Southeast Asia, receptions of and responses to Beijing diverge across and within state lines. Public and eliteopinion surveys suggest that regional elites tend to be more skeptical, while the public is more sympathetic towards Chinese messaging—although U.S. support for Israel over Gaza seems to move elite views toward public ones.

Bearing the brunt of Beijing’s pressure over the South China Sea and proximity to Taiwan makes the Philippines far more wary than its neighbors, even if it has experimented with accommodating China over several administrations, most recently that of former president Rodrigo Duterte. Other countries seem to believe they can have their cake and eat it, too, cultivating closer economic ties with Beijing while simultaneously encouraging the United States, its allies and partners, and others to restrain Chinese ambitions and maintain existing rules. Indonesia stands out as especially confident in its ability to shift positions with little cost, perhaps because of its size and importance in the region.

On one end of a spectrum, states such as Cambodia and Laos tend to see Beijing as integral to their economic and political futures and have close official relations. Both are major destinations for Chinese infrastructure investment. Cambodia receives civil service and police training from Beijing, hosts a Chinese-financed naval base at Ream that the People’s Liberation Army Navy visits, and has even blocked ASEAN statements on the South China Sea that Beijing dislikes. Timor-Leste appears eager to invite investment, as well as support for building its domestic institutions. Despite elite cultivation, however, there is some publicwariness in both Cambodia and Laos about the environmental degradation, corruption, crime, and inequality associated with Chinese capital.

At the other end of a spectrum, Philippine elite and public sentiment have hardened toward Beijing after years of unrelenting pressure over disputed maritime claims and the failure of efforts to mollify Beijing through engagement.

Other Southeast Asian states are more ambiguous, even split, toward Beijing. Thai establishment elites desire deeper economic and security engagement, but this orientation exacerbates a cleavage with younger people who are wary of the autocratic tendencies of the Thai establishment and their friends in China. In Malaysia, where public opinion favors Beijing but elite sentiment is mixed, Kuala Lumpur courts Beijing and Chinese entities economically while seeking to diversify capital investment to encompass other sources. Malaysia has also quietly maintained security cooperation with the United States and its allies while playing down China’s pressure on maritime claims. In Singapore, there is substantial public sympathy for China and a broad desire to enjoy more of the economic opportunities that Beijing seems to promise, but there is also a general fear of friction with China’s regime. Singaporean elites generally prefer to maintain robust economic and security ties with other major actors to preserve regional order and limit Beijing’s influence.

Indonesia retains a degree of suspicion toward Beijing given its history of anti-communism and interethnic tensions, reinforced by economic dislocation from low-priced Chinese imports and environmental damage associated with direct investment. Differences also exist over Beijing’s expansive maritime claims. However, Indonesian political and business elites still see significant gains from economic cooperation with China, especially in terms of infrastructure investment. The multisided civil war in Myanmar has various sides trying to win support from Beijing, especially the military, which prompts skepticism toward Beijing in other quarters.

Communist Party–run Vietnam generally tries to maintain its harder-line positions over territorial disputes while preserving positive ties with Beijing through direct party-to-party ties that include both an ideological and an internal security component. These ties may strengthen now that a public security official, To Lam, has become Vietnam’s new leader.

Brunei aims to build stable ties with China, which is a major buyer of its natural gas, and has kept silent about its competing claims in the South China Sea.

Beijing’s desire to advance its interests in Southeast Asia converges with most regional states’ aims to benefit from economic integration. Augmenting these material considerations are relatively popular views in Southeast Asia that China shares “Asian” civilizational, cultural, and historical reference points alongside experiences of resistance to imperialism. Those holding such perspectives find it easier to establish common cause with Beijing as a result.

Obviously, what adequately represents the diversity of “Asian” civilizations, cultures, and experiences remains a subject of robust debate. There remain lingering concerns in Southeast Asia—and beyond—that claims about more singular interpretations of “Asian-ness” by China can mask a desire for domination, as it did for Imperial Japan during the mid-twentieth century.

Beijing seems ready to use notions of “ASEAN centrality” and the grouping’s desire to complicate U.S. and allied calculations in the region, even as China entices and pressures ASEAN members into shunning consensus on matters it deems inimical to Chinese interests. This includes shunning criticism of efforts to occupy, reclaim, and arm features in the South China Sea. Southeast Asian governments looking to extra-regional players to counter China can end up inviting pushback from Beijing, potentially in ways that corrode prevailing practices and rules.

There is significant uncertainty about just what kind of power and influence Beijing will wield in the region in the coming decades. Analysts must keep in mind that although state-to-state relations between China and Southeast Asia have a level of deliberation, interactions by nonstate actors, particularly by business stakeholders and ordinary people on the ground, can have significant, though unintended, consequences in shaping engagement. For example, in May 2014, thousands of angry citizens in the south of Vietnam set fire to foreign factories—some of which were in fact Taiwanese—as part of anti-China protests over tensions in the South China Sea.

Demystifying Southeast Asian ties with Beijing against the backdrop of heightened major power contestation calls for a measured, clear-eyed understanding of the perspectives and impact of different stakeholders, within each country as well as across the region.

To that end, this compendium seeks to present the nuances and varied lenses through which Southeast Asians view China across three issue areas: leadership changes in Southeast Asia, Chinese diplomatic efforts, and Southeast Asia-China economic interactions.

New Leader, New Approach to China?

Charmaine Misalucha-Willoughby, Cheng-Chwee Kuik, Lak Chansok, Thitinan Pongsudhirak, Lina A. Alexandra, Dien Nguyen An Luong, and Lam Peng Er

Has Xi’s Diplomacy been Effective in Southeast Asia?

Chong Ja Ian, Enrico V. Gloria, Nur Shahadah Binti Jamil, Pou Sothirak, Chanintira na Thalang, Christine Susanna Tjhin, and Bich Tran

How Has China’s Belt and Road Initiative Impacted Southeast Asian Countries?

Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbarat, Alvin Camba, Fadhila Inas Pratiwi, Sovinda Po, Hoàng Đỗ, Bouadam Sengkhamkhoutlavong, Tham Siew Yean, and Moe Thuzar

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

Western negotiators often believe territory is just a bargaining chip when it comes to peace in Ukraine, but Putin is obsessed with empire-building.

Andrey Pertsev

When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

German manufacturing firms in Africa add value, jobs, and skills, while benefiting from demand and a diversification of trade and investment partners. It is in the interest of both African economies and Germany to deepen economic relations.

Hannah Grupp, Paul M. Lubeck

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov