Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

The kingdom will need to grow its institutional capacity and ensure its financial commitments match its long-term climate goals.

This primer points out key targets in Morocco’s climate strategies and analyzes the main takeaways from our database on climate governance, outlining how Morocco’s national institutional, regulatory, and legal frameworks interact with its climate mitigation and adaptation goals. The analysis evaluates institutional tools on two axes: sound climate policies and good governance practices. It assesses the country’s climate policies in terms of how well they achieve goals related to establishing long-term, short-term, or foundational targets; addressing risk and vulnerabilities; mitigation; or adaptation. The governance metrics used to analyze the quality of Morocco’s climate framework are based on the following criteria: actionable goals, authority and management powers, transparency, accountability, representation, human capacity, financial capacity, and oversight capacity. By expanding on the database, the primer offers an overview of Morocco’s climate governance, identifies areas of progress as well as institutional gaps, and suggests potential policy actions and plans.

Morocco faces significant environmental challenges, including water scarcity, desertification, and extreme weather conditions exacerbated by climate change. As a semi-arid country, Morocco is particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures, droughts, and reduced rainfall—all of which threaten agriculture, the backbone of the Moroccan economy and a major source of employment. Coastal areas are also at risk from rising sea levels, impacting infrastructure and tourism. These environmental pressures not only strain natural resources but also deepen social inequalities as rural communities, reliant on subsistence farming, are disproportionately affected. Economically, climate vulnerabilities hinder growth, increase food insecurity, and require costly adaptation strategies, making it imperative for Morocco to invest in sustainable solutions to safeguard its people and future prosperity. Morocco’s social, political, and economic conditions are central to understanding the context of the country’s climate governance and evaluating its efficacy.

Morocco is a predominantly Muslim, culturally rich country with a diverse social fabric shaped by its Arab, Amazigh, and European influences. Amazigh communities, while traditionally marginalized, have seen increasing recognition and empowerment—especially since the 2011 constitutional reforms, which granted Amazigh official language status. Morocco’s society is also shaped by its urban-rural divide, with cities like Casablanca and Marrakech being hubs of economic and cultural activity, while rural areas often face higher levels of poverty and limited access to services. Youth unemployment remains a significant challenge contributing to social unrest and periodic protests. These protests often center around issues like economic inequality, education, and governance, reflecting a broader desire for political reform and greater representation. Gender equality has improved in some areas, but women still face societal barriers, especially in rural regions. Morocco’s social landscape is also influenced by its history with France and Spain, as well as the ongoing Western Sahara conflict, which affects national unity and relations with neighboring countries like Algeria.

Morocco’s economy is growing, buoyed by a macroeconomic policy focused on reducing the budget deficit, using innovative financing operations to manage public investments, and increasing the sophistication of the country’s export basket. Morocco has leveraged its advantages relative to both the Middle East and Northern Africa region and the African continent—namely, its renewable energy potential, trade agreements, and sound economic management and infrastructure—to effectively attract foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, it is the only African nation that has free trade agreements with the EU, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and the United States, and as such has unique access to the global market. Morocco’s share of the total FDI in Africa doubled from 2018–2019 to 2022–2023, reaching almost 10 percent, and both renewable and electronic manufacturing (including electric vehicle battery production) are attracting significant quantities of foreign capital. Morocco ranked as the world’s first- and second-most attractive renewable energy market for investments (normalized for GDP) in 2022 and 2023 respectively. While Morocco’s government and state-owned enterprises have expanded their investments and economic participation, there remain significant opportunities to further grow the private sector and drive firm competitiveness. Indeed, the private sector’s domestic investments and productivity performance remain relatively low and its gross capital formation only recently recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Morocco’s economy is also still primarily driven by its agricultural sector, which makes up almost 15 percent of the country’s GDP. While its total labor productivity has significantly increased since 2000, this rise has been driven primarily by progress in agricultural productivity rather than broad growth across sectors.

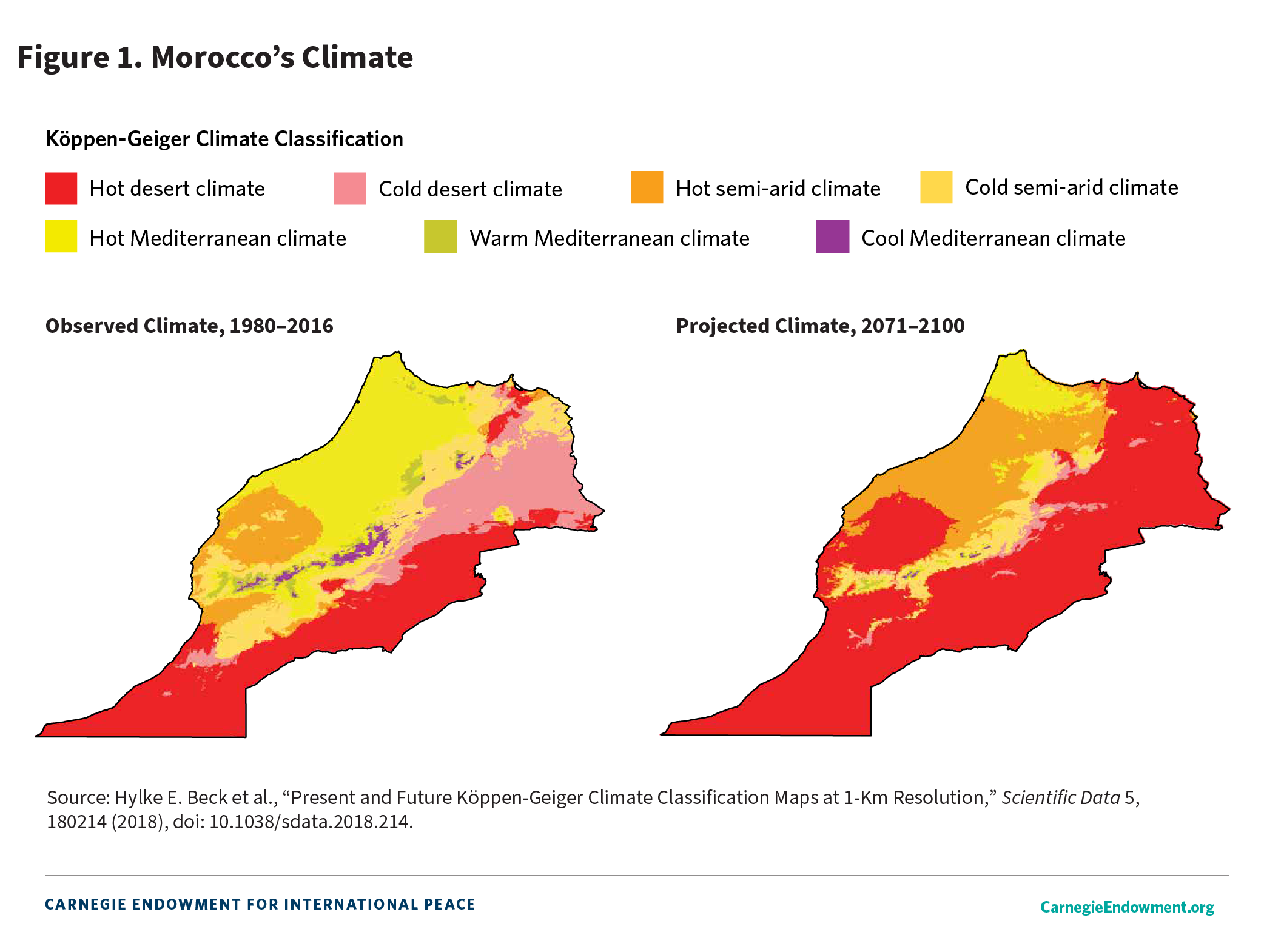

Stretching to the westernmost point of North Africa, Morocco’s climate is varied—arid and desert-like in the south and southeast regions of the Atlas Mountains but temperate and semi-arid in the northern territories. Pressures brought on by climate change have exacerbated the country’s environmental vulnerabilities as temperature and aridity levels increase while precipitation rates fluctuate. In contrast to other countries in the North African region, its economy is not reliant on carbon-intensive industries. As of 2018, Morocco had significantly lower emissions than the global average, producing 0.2 percent of total greenhouse gases and situated at 38.5 percent under the global average for emissions when adjusted for purchasing power. However, its economy remains vulnerable to the consequences of climatic changes. As an example, agriculture is highly sensitive to environmental conditions: a 1.6 percent decrease in aridity levels in 2016 led to a 4 percent increase in the country’s economic growth the following year. As such, the country’s climate strategies must not only target adaptation and mitigation but also economic diversification to relax Morocco’s dependency on sectors subject to fluctuations from environmental stressors.

Morocco’s environmental strategies are driven by three main documents: its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC); its National Sustainable Development Strategy for 2030; and its National Climate Plan (NCP) for 2030. The National Sustainable Development Strategy, which lays out the green economy standards Morocco is striving toward, provides the foundation for both the NCP and the NDC. It guarantees international compliance and compliance with the principles of the National Charter for the Environment and Sustainable Development (Law No. 99-12) through stakeholder engagement and an operational strategy. The NCP mirrors the National Sustainable Development Strategy’s focus on building governmental capacity, addressing social and environmental vulnerabilities, and deploying a mitigation and adaptation strategy with the following goals:

The NDC sets clear targets, presents the scope of the country’s national actions, and explains the methodology that drives their framework. In terms of its climate strategy, Morocco targets thirty-four unconditional measures to reduce 18.3 percent of its business-as-usual emissions—the estimated cost of which would total $18 billion. The plan also outlines twenty-seven projects conditional on international financing and support that would enable a more ambitious goal of 45.5 percent reduction by 2030.

The updated NDC expands the scope of sectors included in the country’s climate target, focusing on sectors that are both carbon-intensive and key to the Moroccan economy. The industrial sector, for example, represents 50 percent of the national climate objectives in the NDC, with phosphates alone at 27.5 percent. Other key sectors include agriculture, land management, and urban development. Morocco seeks to reduce total electricity consumption by 20 percent in 2030, targeting a wide array of industries including transportation (24 percent of total reductions), industry (22 percent), building (14 percent), and agriculture (13 percent). These efforts are paired with a goal of increasing electricity supplied by renewable energy sources up to 52 percent by 2030. Waste treatment is another major cross-sectoral effort with clear targets: recycle household and industrial waste at 20 percent and 25 percent respectively and increase the treatment of agricultural wastewater from 60 percent to 100 percent by 2030.

Building on these efforts, Morocco has set an ambitious national low-carbon strategy with the objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, a commitment presented at COP28 in Dubai by the minister of energy transition and sustainable development. The road map focuses on decarbonizing key sectors of the economy, including energy, transport, industry, and agriculture, with a central goal of increasing the share of renewable energy sources—especially solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. The strategy also emphasizes sustainable urban development practices and improving the efficiency of industrial processes, as well as adopting green technologies in sectors like transportation and agriculture.

Morocco’s adaptation strategies are guided by three primary objectives that seek to correct the challenges to address environmental vulnerabilities:

Morocco’s adaptation strategies target sectors across the economy, such as agriculture, water management, fishery and aquaculture, forestry, and territorial and urban management.

Given the Moroccan government’s priorities as outlined in its national climate strategy, this database focuses on the following three ministries: the Ministry of Equipment, Transport, Logistics, and Water; the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fishery, Rural Development, Water, and Forests; and the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development. This underlines the country’s need for greater institutional capacity; publicly available regulations are necessary for coordinating effective strategies across sectors and levels of government. This lack of transparency also creates obstacles for nonstate actors—including civil society groups, the private sector, and development organizations—seeking to contribute to climate efforts.

Morocco has dedicated an increasing share of its budget to government institutions concerned with water, agricultural and ecosystem management, energy and sustainable development, and socioeconomic development. While the share was only 1.71 percent in 2016, this proportion has stayed between 6.48 percent and 8.91 percent from 2017 to 2024, reflecting the country’s sustained commitment to its mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Two notable patterns emerge from the kingdom’s public financing structure. First, Morocco has historically placed greater financial capacity in both the Ministry of Water and Equipment and the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fishery, Rural Development, Water, and Forests than in the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development (previously titled the Ministry of Energy, Mines, and Environment) or the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council. In 2024, for example, the Ministry of Water and Equipment enjoyed 3.57 percent of the total government budget, the Ministry of Agriculture 3.92 percent, and both the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development and the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council under 0.5 percent. This reflects both the economic and environmental concerns of the country: water scarcity is a central vulnerability in the kingdom, and agriculture is its largest sector. The relatively small share of public investments dedicated to the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development suggests that developments and deployments in the energy sector may be driven by foreign investments or financing from multilateral groups. The state-owned Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy, for example, mobilizes financing from different international institutions to support project companies.

Second, the Ministry of Water and Equipment and the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fishery, Rural Development, Water, and Forests—the two best-funded ministries—both receive more financial support for their investment programs than for their operational budgets. Importantly, public investments significantly benefit the country’s economic output in both the short and the long term, and attract private sector research and development investments.

Morocco’s institutional tools—ministerial laws, decrees, and decisions—evaluated in our database showcase organizational mandates and functions, policy planning, implementation processes, and mechanisms for stakeholder engagement mainly led by the Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development; the Ministry of Energy, Mines, and Environment; Ministry of Water; and the Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fishery, Rural Development, Water, and Forests. These procedures and standards specifically address conducting environmental impact and assessment studies, mitigating harmful practices in high-emitting sectors, managing water and energy resources efficiently, financing climate strategies, building public awareness and knowledge, and integrating institutional capacities.

All thirty-one institutional tools assessed in the database sufficiently meet our “transparency” criterion, which means the stakeholders involved and the method of the policy’s design, development, or execution are clearly stated in a law, decree or royal decree. Decrees No. 2-09-284 and No. 2-07-253 and Joint Decision 1653-14 delineate clear criteria for measuring and maintaining air and water quality and waste management practices protective of human and environmental health. In addition to this, most plans of action covered in the database are accompanied by specific implementation timelines and accountability measures; 77 percent of the policies in the database demonstrate sound pathways for oversight and/or enforcement responsibilities. Positive indicators of transparency and oversight capabilities include creating new bodies to exclusively lead oversight activities, holding periodic discussions with involved entities, and submitting yearly reports on committee activities (which makes it easier to assess progress and accordingly reevaluate strategies). For instance, the Committee on Polychlorinated Biphenyl Compounds, established by Decree No. 2-08-243, is tasked with ensuring requirements from the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants are met by examining the environmental impact of activities and drafting an agreement detailing preventative recommendations and solutions; this process includes government authority representatives from all relevant sectors: finance, water, energy, agriculture, interior, transportation, health and defense.

The Moroccan government’s oversight mechanisms are especially effective because of the prevalence of public-private partnerships in its energy sector. The Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Development (whose framework can be found in Law No. 57-09) serves as a prime example of multi-stakeholder and cross-sectoral engagements. Morocco has also championed private-sector leadership for environmental impact assessments and monitoring procedures for air quality standards, as seen in Decrees No. 2-04-563 and No. 286-09-2 and Law No. 13-09. Further, 61 percent of the policies in the database identify and acknowledge the needs of both public and private stakeholders affected by climate events and policy decisions. Morocco’s climate governance structures thus prove to be adequately inclusive of public and private actors.

Regarding mitigation/decarbonization, flooding, and waste collection/management, Morocco has effectively created channels for multilevel governance and institutionalized collaboration between and within national, regional, and provincial authorities, a key component of its national climate adaptation plan. In addition to the Regional Committee for Environmental Impact Studies and the National Committee for Sustainable Development, Decree No. 1-16-113 and Decree No. 2-09-683 establish committees nationally, regionally, and locally to manage and follow up in cases of flooding as well as to track and impose fines for violations in agricultural, household, industrial, and medical waste management. Assigning reporting and monitoring responsibilities to local authorities is necessary for bettering oversight, human capacity, and access to high standards of sustainability at the local level.

Although agriculture is cited as a primary adaptation priority, Morocco’s regulatory frameworks have so far failed to issue protections that adequately target the economic and infrastructural vulnerabilities facing agriculture; the same can be said for Morocco’s approach to its coastal sector, another claimed policy priority. According to the database, reducing agricultural waste (Decree No. 2-09-683) and conducting public research on sustainable agriculture and the effects of climate change on agriculture (Decree No. 2-09-683) were the extent of Morocco’s regulatory strategy for agriculture.

Morocco has demonstrated a strong commitment to public research as a stepping-stone for integrated management and advanced and reinforced human capacity, representation, accountability and oversight. Decree No. 2-04-564 maps out clear technical expectations for public research related to projects monitored by the Regional Committee for Environmental Impact Studies, signaling that major projects will be rolled out according to high-quality research standards. Decree No. 2-21-965 similarly promotes employing research and innovation as part of Morocco’s National Coastal Plan. Lastly, Decree No. 2-09-683, which aims to present a regional waste management plan, creates a council for conducting public research to be published in local universities or at least two newspapers; more importantly, the decree mandates the advisory committee drafting the regional plan is to take into account conclusions drawn from public research, demonstrating how research is also used as a tool for incentivizing adaptable policies compliant with accurate data and representative of citizens (at large) affected by climate issues and policy decisions.

Morocco has also taken steps to align its ministerial laws and regulations with its national development strategy through the National Electricity Regulatory Authority (ANRE). Under Royal Decree 1-16-60, ANRE is responsible for enforcing and overseeing the implementation of a five-year investment plan to improve the energy efficiency of the national high-voltage electrical transmission grid, which spans almost all regions of Morocco with interconnections to Spain. The plan promotes energy efficiency by imposing tariffs on producers and energy providers that disrupt energy supplies to consumers and mobilizes renewable energy investments by reducing competition barriers. While strong financial capacities are lacking in other key sectors, this plan illustrates Morocco’s commitment to its national development strategy, which urges applying financial incentives to garner compliance with clean energy goals.

With 42 percent of policies from the database outlining a path to decarbonization, emissions reduction is adequately targeted in Morocco’s climate governance framework. Similarly, 38 percent of policies in the database target adaptive capacity, which includes building climate-resilient infrastructure, disaster risk–management planning, land preservation, and water management. However, despite the mobilization of water resources being a key pillar of Morocco’s national plan, only two decrees (Decree No. 2-96-158 and Decree No. 1-16-113) are devoted to enabling a rational and sustainable use of water and improving the valuation of water. One of those two decrees (Decree No. 2-96-158) created the Superior Council on Water, which aims to address Morocco’s water scarcity issues and help develop national strategies to manage the country’s water resources. Yet the remaining regulations focus on water management in the context of pollution and flooding, demonstrating that in order for Morocco to optimally strengthen adaptive capacity and climate resilience, it must better streamline water governance to meet not only immediate mitigation needs but long-term (infrastructural) adaptation needs.

Effective and streamlined governance also comes with accountability and representation, which are lacking in most of Morocco’s water-related laws. Beyond the water sector, Morocco’s climate governance framework overall also lacks incorporated short-term and long-term planning, with only one long-term-oriented law and six short-term-oriented laws. Per the database criteria, “long-term” targets are meant to be achieved by 2050–2060 and “short-term” targets are meant to be achieved by 2030. Timeline and accountability are inextricably linked; no documentation of timelines makes it less likely for Morocco to succeed in meeting its target and not only meet but continue to adapt its goals in order to ensure optimal results to eliminate climate risks and vulnerabilities.

Morocco’s efforts to address climate change reflect a dynamic and evolving governance framework that blends national priorities with international commitments. Through national roadmaps—the NCP, the National Sustainable Development Strategy, and the updated NDC—and government–led campaigns, Morocco has taken substantial steps to advance both mitigation and adaptation strategies. These initiatives underscore the country’s focus on building climate resilience in sectors such as energy, water, and agriculture while leveraging its renewable energy potential to attract foreign investment and diversify its economy. However, challenges remain in streamlining governance, enhancing institutional capacity, and ensuring financial commitments align with long-term goals, particularly in sectors like agriculture and water management, which are most vulnerable to climate stressors. Notably, agriculture is a primary driver of Morocco’s economy, and a lack of effective mitigation and adaptation policies in this sector could pose significant risk over the medium-to-long term as climate pressures will likely disrupt yields.

To fully realize its climate ambitions, Morocco must address key gaps in regulatory frameworks, improve accountability mechanisms, and continue to enhance coordination across national, regional, and local levels. Importantly, the climate crisis exacerbates other socioeconomic vulnerabilities: while the kingdom has improved its inclusion of Amazigh populations, for example, they remain at greater risk of displacement from large-scale clean energy projects. Continuing to prioritize sustainability and inclusion policies along with mitigation strategies is vital. While significant progress has been made through policies promoting transparency, multi-stakeholder engagement, and renewable energy investments, greater emphasis on long-term targets and adaptive infrastructure is critical. By integrating more comprehensive protections for vital sectors and fostering a stronger balance between operational and investment priorities, Morocco can solidify its role as a climate leader in the region. Notably, Morocco has an opportunity to further support the private sector’s participation in its climate strategy, particularly in its mitigation priorities. While foreign and public investments in the clean energy sector have grown significantly, private investments have stagnated. Growing the private sector by undoing key contributors to its lag—for example, by implementing robust anti-competitive practices and developing a more supportive regulatory environment for small and medium-sized businesses—could improve the private sector’s involvement and thus the execution of the country’s climate strategy. Similarly, Morocco’s labor productivity levels in non-agricultural sectors have lagged in the past twenty years, putting into question whether local populations are effectively absorbed into the green economy. The kingdom could further dedicate resources to growing local capacity to facilitate a greater transition away from climate-sensitive sectors and into green jobs.

Ultimately, Morocco’s ability to align its climate governance with economic development will determine its success in overcoming environmental vulnerabilities and achieving sustainable, inclusive growth for its people.

Note: This piece has been updated to discuss Morocco’s low-carbon strategy presentation at COP28.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

Supporters of democracy within and outside the continent should track these four patterns in the coming year.

Saskia Brechenmacher, Frances Z. Brown

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

Regional free movement agreements, like that of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, offer unique potential to address the human mobility challenges posed by the climate crisis.

Liliana Gamboa, Debbra Goh

2026 has started in crisis, as the actions of unpredictable leaders shape an increasingly volatile global environment. To shift from crisis response to strategic foresight, what under-the-radar issues should the EU prepare for in the coming year?

Thomas de Waal