South Korea has emerged as a major weapon exporter. But its relationship with Europe will depend on more than that.

Chung Min Lee

Source: Getty

As more South Korean men perceive marriage as unattainable, their politics disfavor gender equality and reinforce sexism. These attitudes likely make marriage less appealing to women, which in turn fuels backlash among men.

The 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey1 and the 2024 Carnegie California Embrain Korea Survey,2 administered with Gallup and Embrain, respectively, offer a new and detailed examination of how South Koreans think about issues regarding gender.3 The surveys confirm that an alarming gender and generational divide with regards to gender attitudes exists in South Korea, and this divide reflects broader ideological shifts, underscoring the pressing need for evidence-based targeted interventions, policy solutions, and expanded efforts to counter this trend.

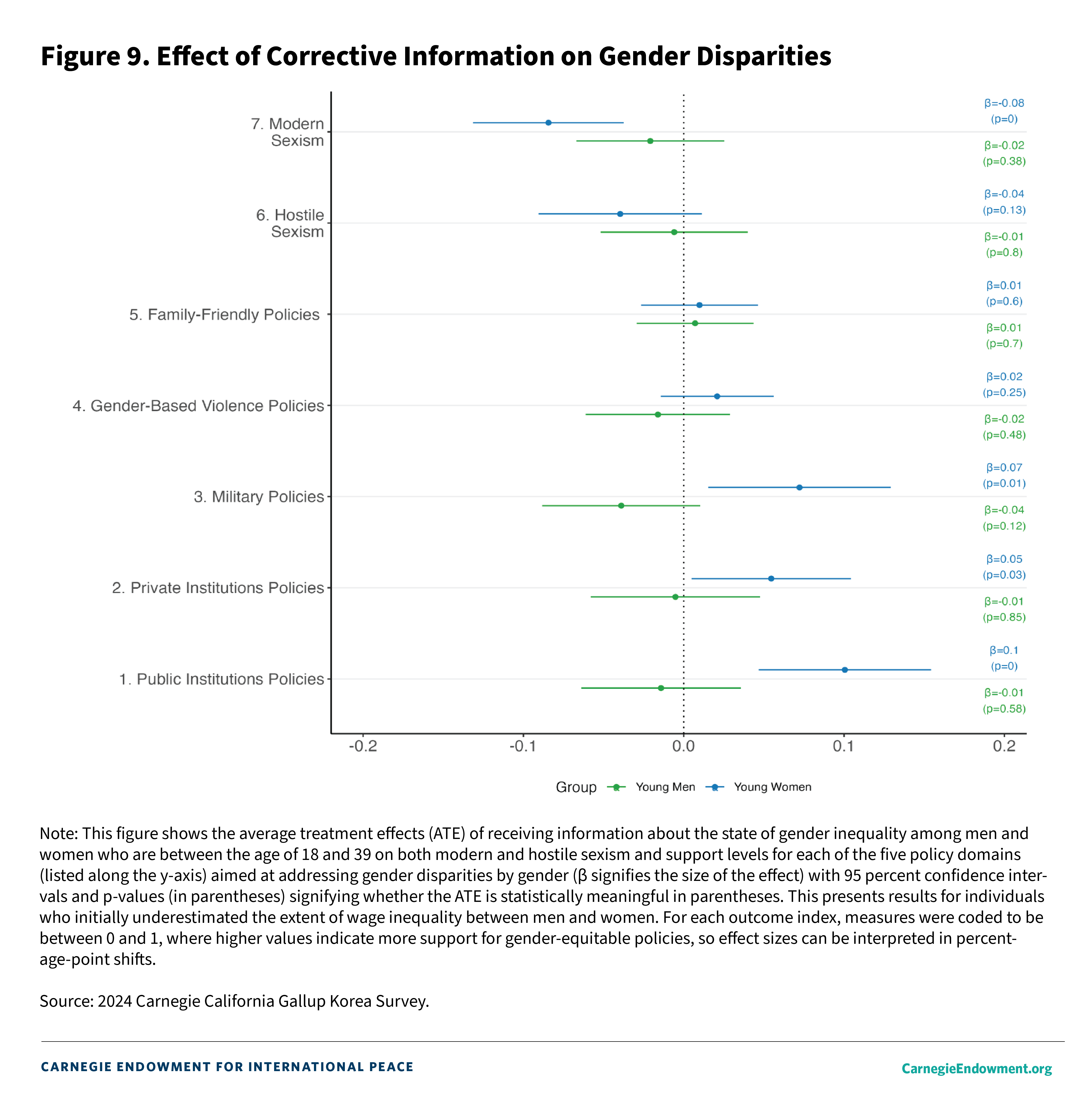

Survey results also highlight that addressing this divide is a complex challenge. While part of this division stems from the erroneous belief that gender discrimination is no longer a pressing issue, dispelling this misconception is not straightforward. Currently, younger men are particularly prone to downplaying gender disparities; however, the provision of information regarding the degree to which gender disparities exist in Korea does little to bridge the gender divide. Rather, efforts to highlight realities regarding gender gaps in the economic, political, and social spheres exacerbate the divide. While young men remain largely unaffected by this information, young women, upon realizing that gender disparities are more severe than they had previously believed, respond by advocating for more far-reaching policies to advance gender equality.

Demographic shifts and evolving marital dynamics are also key factors contributing to the antifeminist backlash in South Korea. Recent research by Soosun You identifies the marriage market squeeze—where men outnumber women in the marriage market—as a critical driver of opposition to gender-equality policies. You argues that the imbalance is shaped by decades of anti-natalist policies, son preference, and growing social and economic constraints that have led young women to increasingly opt out of marriage, exemplified by the 4B movement—a movement initiated by young Korean feminists advocating the rejection of heterosexual marriage, childbirth, romantic relationships, and sexual engagement.

Building on You’s study, findings from the 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey confirm that men’s resistance to women’s empowerment intensifies when they are made aware of the gendered marriage gap. Unmarried men, in particular, show lower support for policies to advance women’s empowerment. Beyond policy resistance, unmarried men also express greater hostility toward women, endorsing both overt and subtle forms of sexism. These findings highlight how shifting marriage dynamics shape attitudes toward gender equality and can fuel resistance to policies designed to address systemic disparities.

Finally, findings from the 2024 Carnegie California Embrain Korea Survey show that economic and status anxiety play a crucial role in shaping attitudes toward gender equality, but not always in expected ways. Improving a young man’s status or removing his financial struggles does not necessarily translate to greater support for gender-equality policies. Improvements in his economic position could translate to gender backlash if his perceived status fails to keep pace with his aspirations. The status aspiration gap—the distance between where young men see themselves and where they believe they should be—emerges as a powerful predictor of resistance to gender-equality initiatives. Those with a wider gap are significantly less supportive of gender-equity policies and show substantially higher levels of both hostile and modern sexism. Relative economic standing also plays a role, with young men (women) who see themselves as relatively poorer being less (more) likely to back gender-equality efforts than those who do not. This finding aligns with the work of Kosec, Mo, You, and Boittin, who found that regressive gender norms may take hold in places where the population feels relatively deprived, even if they are not absolutely deprived. Ultimately, these findings suggest that beyond one’s actual economic circumstances, the perception of falling behind others and the sense of being distant from one’s aspirations can drive resistance to gender equality.

South Korea has emerged as a global leader in culture and technology, yet its rapid economic transformation into one of the world’s wealthiest nations has not been equally experienced by women, who continue to face significant disparities. In fact, a recent study by the Economist put South Korea in last place among industrialized nations in the “glass ceiling index,” which measures the gender gap in education, wages, managerial positions, political representation, and other areas. Despite this, young men in Korea are increasingly claiming that attempts to reduce gender inequality are acts of reverse discrimination, and an anti-feminist movement is galvanizing this important voting bloc.

Yoon Suk Yeol, who was impeached in 2024 and recently dismissed from the presidency by the Constitutional Court, won the presidential election in 2022 on an explicitly anti-feminist agenda, with a promise to get rid of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. And some of the most fervent supporters of Yoon, who is now facing charges of insurrection after his failed martial law decree, are young men. Following the National Assembly’s vote to impeach Yoon, large-scale protests have erupted nationwide, with opposing groups demanding either his prosecution or reinstatement. Notably, anti-Yoon demonstrations have seen a surge in participation from young women, while pro-Yoon rallies have drawn a large number of young men.

Men in their 20s feel that they are the newly marginalized group, and on several dimensions, they express more conservative gender views than men who are 60 years old or older. Accordingly, the Yoon government has responded with an array of public sector efforts to roll back policy and programmatic investments that have been put in place to address issues of gender inequality. For example, the Yoon administration removed the term “gender equality” from the school ethics curriculum and discontinued funding for programs aimed at addressing everyday sexism.

Young women are balking at this sentiment. A 2021 Ipsos poll revealed that South Korea had the highest reported tensions between men and women among the twenty-eight countries surveyed. And this tension is evident in the ballot box. In recent major elections, young South Korean men and women have consistently exhibited a 15 to 30 percentage-point disparity in their support for the country’s main political parties, with young men supporting the country’s major conservative and right-wing political party—the People Power Party (PPP)—and young women more likely to support the country’s major liberal political party—the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK).

Alarmingly, while political division by gender is less pronounced in other countries than in South Korea, it is beginning to surface in other advanced economies. For example, a similar trend has emerged among younger voters in Germany. In the 2025 Bundestag elections, Germany’s far-left Die Linke party garnered the most support among young women aged 18–24, while the most favored party among their male counterparts was the far-right AfD party. In the United States, similar political divides are also becoming increasingly evident. Recent Gallup polling reveals a striking 30-percentage-point gap between women and men aged 18–30 in self-identified liberal ideology; this gap is five times wider than it was in 2000. This divide had primarily emerged as young women shifted further left, while young men have remained relatively ideologically consistent. However, recent surveys indicate a growing trend among young men in the United States toward conservatism and increasing opposition to feminist perspectives—a pattern similar to what has been unfolding in South Korea.

During South Korea’s democratization, efforts to advance women’s empowerment were largely sidelined, despite early leaders recognizing gender inequality as inconsistent with democratic principles. It took decades after democratization for women to secure fundamental rights.4 Today, the growing anti-feminist movement animating young men threatens to erode the hard-won but still insufficient progress toward gender equality.

This backlash also risks exacerbating South Korea’s record-low total fertility rate of 0.72 in 2023—equivalent to just 72 births per 100 women—well below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1 children and the lowest in the world. Since 2020, deaths have outnumbered births, and young women are increasingly rejecting parenthood at higher rates than young men. Citing entrenched gender inequality and patriarchal norms, millions of young women have collectively chosen not to have children, engaging in what has been described as a “birth strike,” further challenging South Korea’s demographic sustainability, democracy, and long-term stability.

The 2024 Carnegie California Gallup and Embrain Korea Surveys paint a striking picture of South Korea’s deepening gender and generational divide, a fissure that reflects, in part, broader ideological shifts, economic anxieties, and demographic transformations. The surveys reveal that gender discrimination remains a pressing issue in South Korea; however, young men generally think otherwise, and efforts to present empirical evidence on gender disparities exacerbate, rather than bridge, this divide. The surveys also underscore the growing significance of the marriage market squeeze, a phenomenon where men outnumber women in the marriage market. Decades of anti-natalist policies and son preference, coupled with a growing number of women opting out of the marriage market altogether, have led to a gender imbalance that is stoking opposition to gender-equality measures. Unmarried men, acutely affected by this gap, not only resist policies promoting women’s empowerment but also display heightened hostility toward women. Compounding these dynamics is the role of economic and status anxiety: young men who are poor or feel relatively poor and perceive a widening gulf between their aspirations and reality exhibit stronger opposition to gender-equality initiatives, reinforcing a backlash rooted not only in absolute deprivation but also in the perception of relative decline. The implications are clear: addressing South Korea’s gender divide will require more than data-driven persuasion and economic advancement. These findings also make it painfully clear that economic growth alone will not mend deep social rifts. If South Korea wants to reverse its growing gender divide, policymakers will need to confront the challenging (and emotional) realities of economic resentment and anxiety, shifting demographic patterns, and ideological backlash head-on—with strategies that go far beyond the usual technocratic fixes.

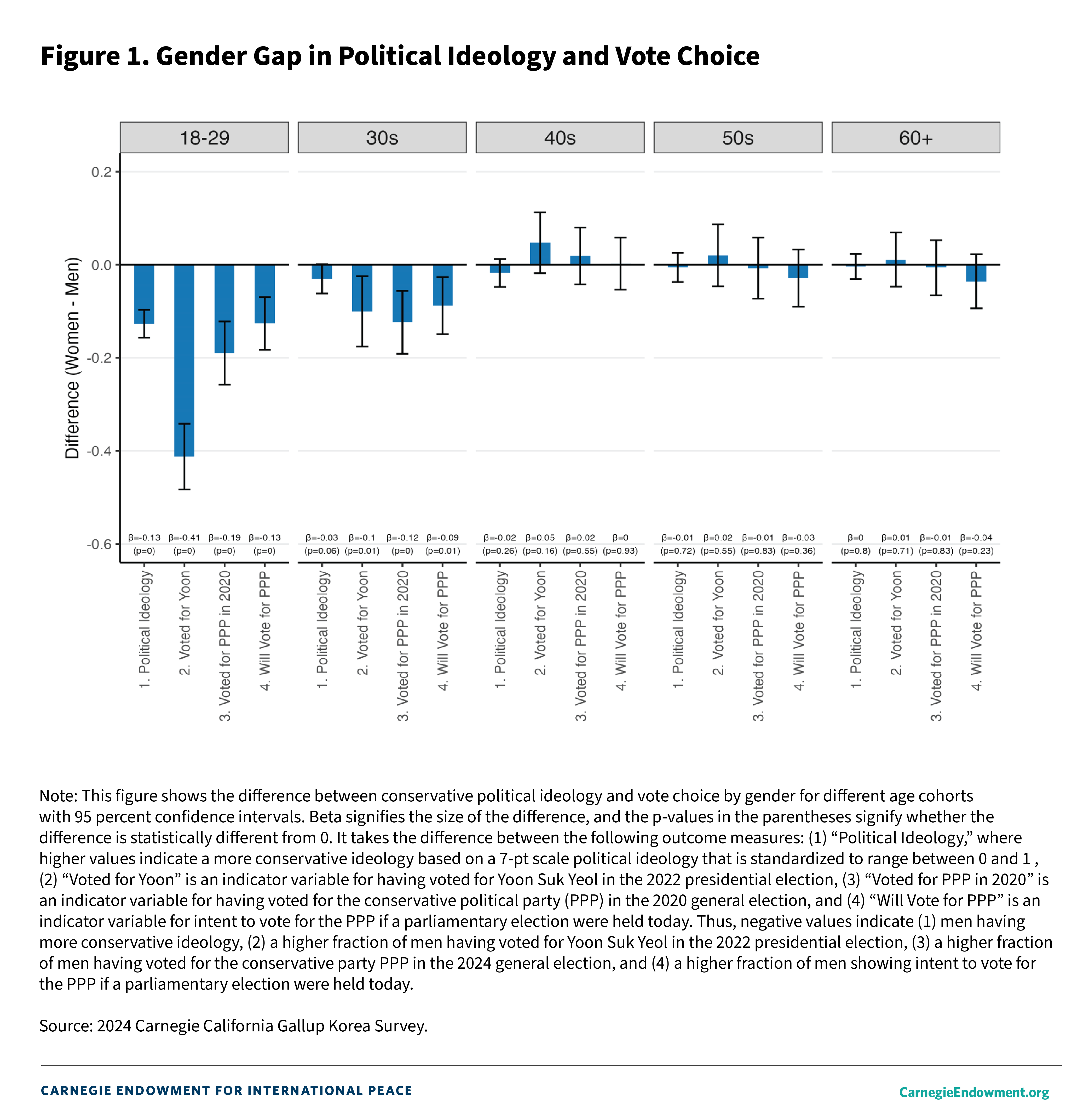

There is a massive political divide in South Korea between young men and young women. An examination of political ideology and party identification by gender and age cohorts in the 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey corroborate past studies and accounts that speak to a widening ideology gap between these two groups (see Figure 1). Among individuals in the 18–29 age bracket, there are significant gender-based differences in political ideology and electoral preferences.5 According to a 7-point scale political ideology measure, men and women in this age group have a 13-percentage-point ideological gap, with women leaning more liberal than their male counterparts. This ideological gap is reflected in electoral behavior: in the 2020 parliamentary election, there was a 19-point difference in vote choice for the People Power Party (PPP) candidate, while in the 2022 presidential election, support for Yoon Suk Yeol, the PPP candidate, differed by 41 percentage points between young men and women.6 Even after Yoon’s failed declaration of the martial law decree, a large gender gap in young voters’ intent to vote for the PPP candidate in future parliamentary elections remained.

These differences consistently indicate that young men are more conservative and right-leaning than their female counterparts. Gender-based disparities in ideology and partisanship are also evident among those in their 30s, although they are less pronounced. Among individuals aged 40 and older, gender-based differences in political ideology, party affiliation, and vote choice are essentially nonexistent, which showcases how the ideological fault line by gender only exists among youth.

Findings in both surveys remain largely consistent (see Figure A1 in Annex 1), with one notable exception: on average, both men and women signaled they were less likely to vote for a PPP National Assembly candidate if general elections were held today. This divergence is unsurprising, given that the 2024 Carnegie California Embrain Korea Survey was conducted shortly after Yoon’s failed attempt to impose martial law in December 2024. In the wake of this political crisis, public support for the PPP—Yoon’s party—declined.

Interestingly, this decline is evident among men across all age groups except for those between 18–29. Among young men, intent to vote for the PPP parliamentary candidate is roughly the same between the Embrain survey and the Gallup survey, the latter of which was conducted before the failed decree. This stability among younger men, in contrast to declining support in other male demographics, underscores the need for generational nuance in examining political realignments after major political events and the persistent loyalty of many young male voters towards conservatism.

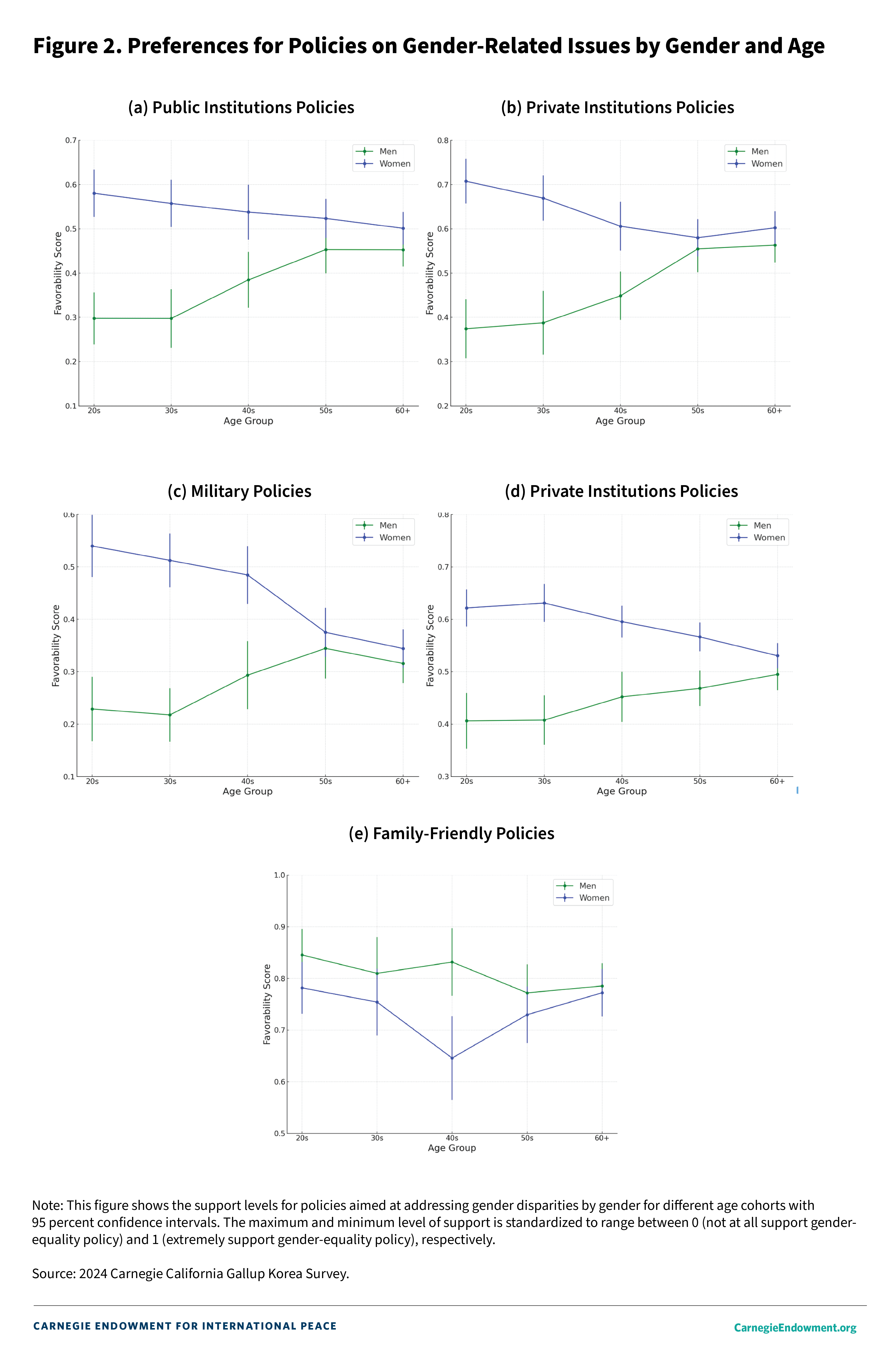

The widening gender gap is also evident in policy preferences.7 Among younger age groups, particularly those aged 18–29, there are stark divisions in support for various policies. When examining support for a broad set of policy proposals aimed at increasing women’s representation in politics (hereafter, referred to as questions regarding “public institutions”; see Figure 2[a]), there is a 28-percentage-point gap between men and women. A 33-percentage-point gap is present when considering policy proposals aimed at boosting women’s representation in corporate leadership and management roles (hereafter, referred to as questions regarding “private institutions”; see Figure 2[b]). This pattern is also evident when examining policies that favor veterans, which implicitly favors men given the country’s mandatory military service requirements for male citizens (hereafter, referred to as questions regarding the “military”; see Figure 2[c]) with a 31-percentage-point difference among those between 1829. Additionally, there is a 22-percent-point gap in support for policies to reduce gender-based violence (hereafter, referred to as questions regarding “gender-based violence”; see Figure 2[d]).

Taken holistically, these data also demonstrate that young men, on average, oppose all sets of policies aimed at addressing gender disparities—average levels of support are consistently below 0.5, where 0 represents opposition, 0.5 represents neutrality, and 1 represents support. In contrast, young women, on average, support all of these policies—average levels of support are consistently above 0.5.

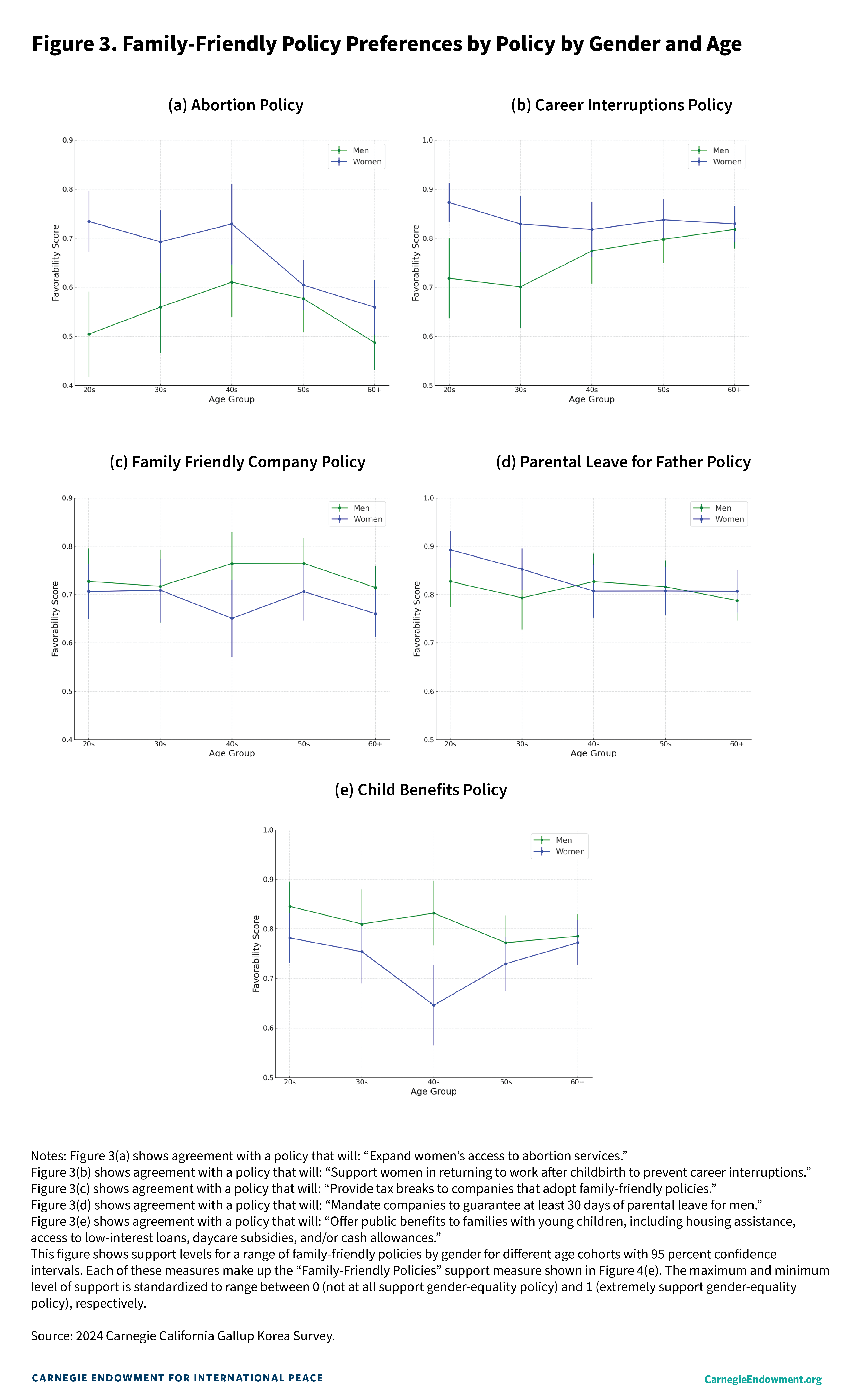

The only index where there was a high level of support regardless of gender (that is, above 0.5 for men and women of all age groups) was one pertaining to policies regarding reproductive rights and family-friendly policies, like expanding family leave and subsidizing childcare (hereafter, referred to as “family-friendly” policy questions; see Figure 2[e]).

This observed exception to the broader pattern is largely driven by support for policies aimed at reducing the cost of child-rearing (see Figures 3[c] and 3[e]) and providing fathers with parental leave benefits (see Figure 3[d]). These policies are less likely to be seen through a zero-sum lens, unlike policies related to political or corporate leadership, such as reserving a certain share of leadership roles for women (which implies men cannot hold those roles), or policies aimed at dismantling veterans’ benefits—often seen as favoring men due to Korea’s mandatory military service requirements for male citizens.

Family-friendly policies that enable working mothers to return to work (see Figure 3[b], however, do reveal a small gender divide among those in their 20s and 30s. Some young men may perceive such policies as benefiting only women. With that said, young men are, on average, supportive of such a policy, which would likely benefit men with children too as households are increasingly reliant on dual incomes. Where there is a widening gap is with regards to reproductive rights (see Figure 3[a]); however, young men, on average, do not oppose efforts to increase reproductive rights.

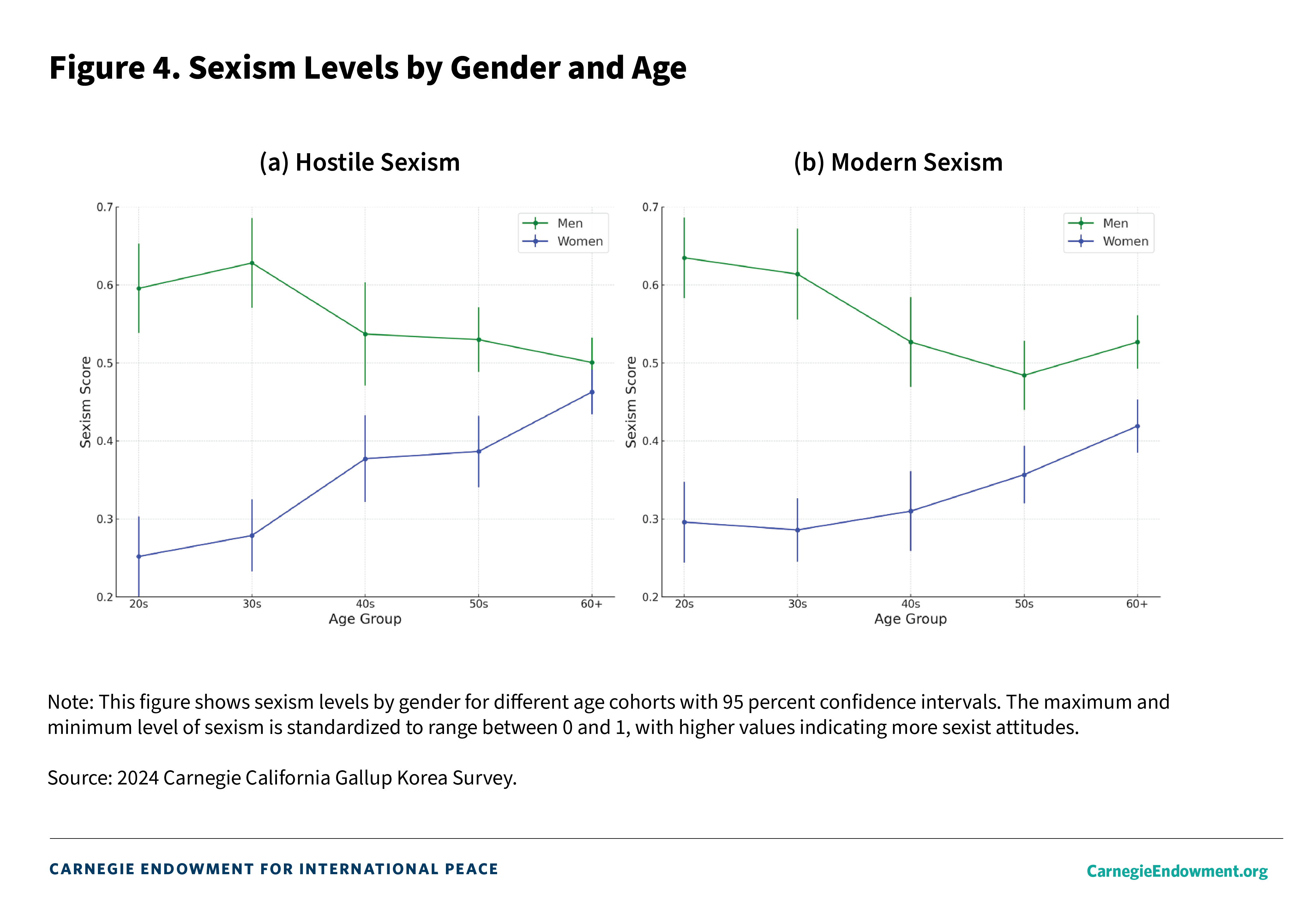

The observed gender gap in policy preferences reflects shifts in the prevalence of sexist attitudes.8 Examining two widely studied dimensions of sexism—hostile sexism and modern sexism—reveals that young men exhibit higher levels of sexist beliefs compared to women of any age group and older male cohorts (see Figure 4). Hostile sexism is a measure of overtly negative or misogynistic beliefs about women; those who espouse this type of sexism view gender equality as an attack on masculinity or traditional values and aim to undermine movements such as feminism. Modern sexism, by contrast, is a measure of a subtler version of sexism, characterized by the denial of gender discrimination and resentment toward efforts to address gender disparities. The pattern among young women, however, stands in stark contrast. In other words, the gender gap in sexist attitudes is expanding: young men, on average, endorse more pronounced sexist views than their older counterparts, and young women, on average, endorse less sexist attitudes than their older counterparts.

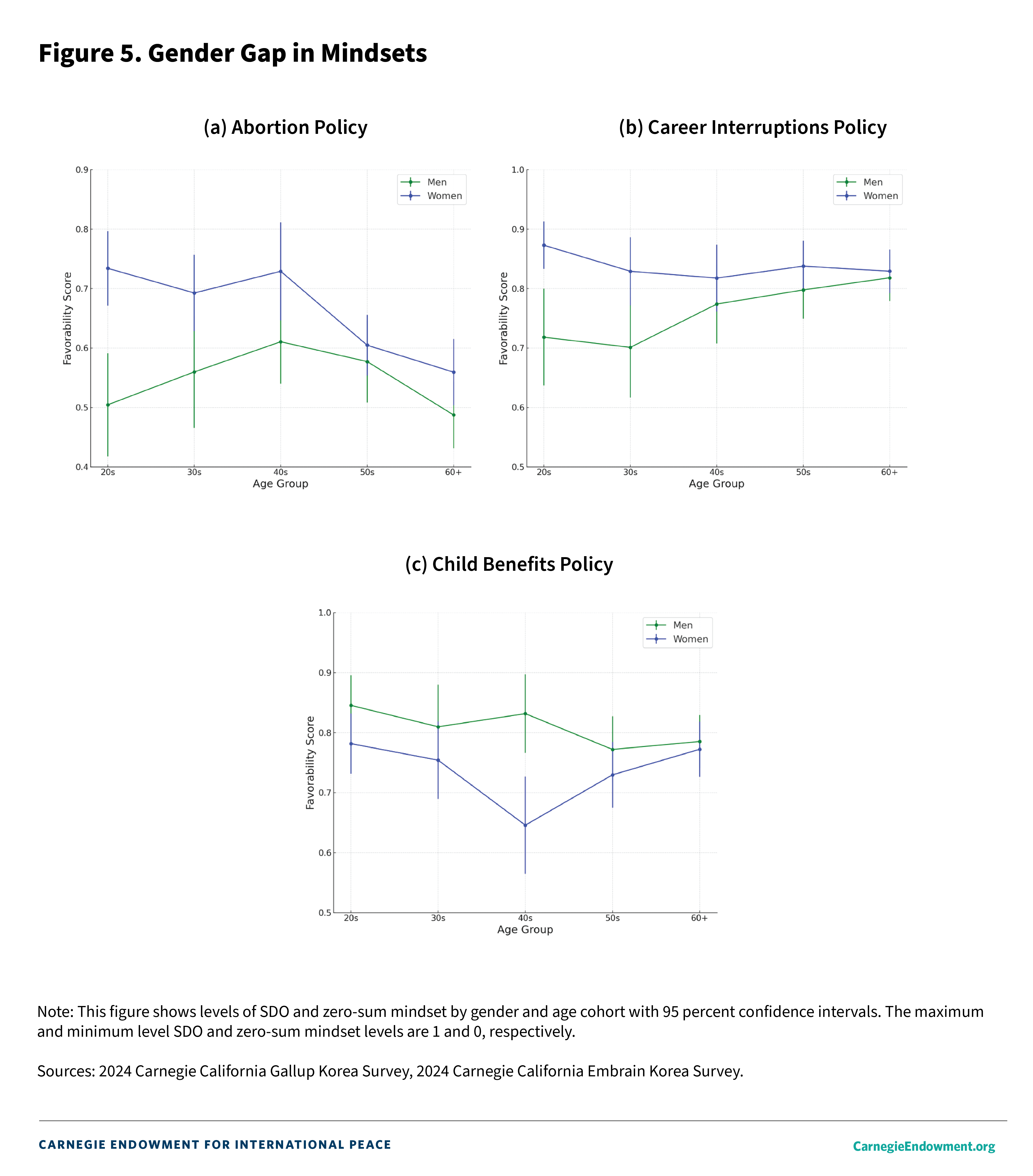

Significant gender differences are also evident when we examine mindsets, or the mental model individuals use to interpret the world around them, that affect views regarding equality and cooperation (see Figure 5[a]).9 Young men exhibit higher levels of social dominance orientation (SDO)—a measure of preference for hierarchy and inequality among social groups—compared to both older men and young women. Among men, there is a negative relationship between age and SDO, with those in their 20s and 30s displaying the highest levels, whereas no such age-related pattern is observed among women. Consequently, a pronounced gender gap in SDO exists among younger cohorts. The pattern is identical in the Embrain survey, with a more extensive set of SDO questions (see Figure 5[b]), which provides additional reassurance that this growing gap in SDO is real, and not an artifact of the survey. In fact, the differences are more pronounced when a more robust set of SDO survey measures are employed.

A similar, though less striking, trend is evident in attitudes toward zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain necessarily comes at another’s expense (see Figure 5[c]). A zero-sum mindset makes one person or group’s success incompatible with another’s. Young men are more likely to endorse this perspective than young women and their male elders, with the gender gap in zero-sum thinking most pronounced among those in their 20s, though it remains noticeable among those in their 30s and 40s.

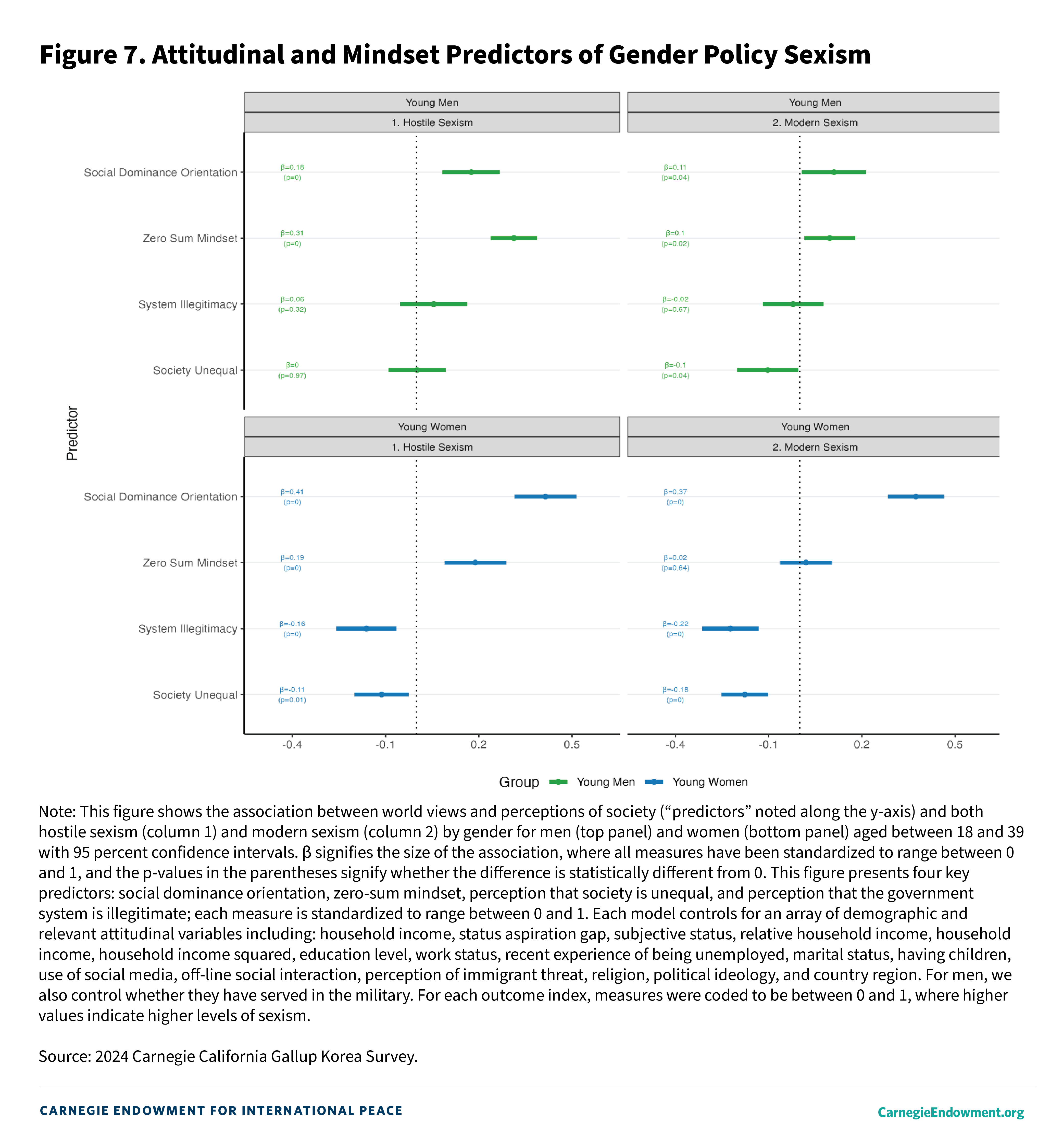

These patterns raise several important concerns. Studies have demonstrated that SDO is a causal predictor of prejudice and discrimination. Competitively driven motivation for intergroup dominance is an antecedent of sexism and racism, and is negatively associated with tolerance, communality, and altruism. Indeed, we see that SDO is a strong predictor of sexist attitudes (see the positive associations between SDO and both sexism measures in Figure 7) and distaste for policies to address gender inequality (see the negative associations between SDO and gender policy support in Figure A2 in Annex 1). We see this pattern when we also conduct a LASSO regression, a machine learning technique to make predictions, considering a wider set of demographics, economic, social, and political predictors. For both young men and women, higher SDO levels are associated with opposition to policies to improve representation in government and corporate leadership, and to reduce gender-based violence. Additionally, higher SDO levels are associated with higher levels of hostile sexism and modern sexism.

While zero-sum thinking is less predictive of policy beliefs on gender-related issues, zero-sum thinking is consistently a negative predictor of support for policies that would help address gender inequality (see Figure A2 in Annex 1). For young men, it is also positively associated with both hostile and modern sexism, and for young women, it is positively associated with hostile sexism (see the positive associations between zero-sum thinking and sexism measures in Figure 7).

Such belief systems also stifle cooperation between groups, even when such cooperation could greatly benefit both parties, which leads to greater intergroup conflict. These patterns are also at odds with conventional wisdom that younger cohorts are more inclusive and open-minded in their attitudes toward out-groups than older generations.

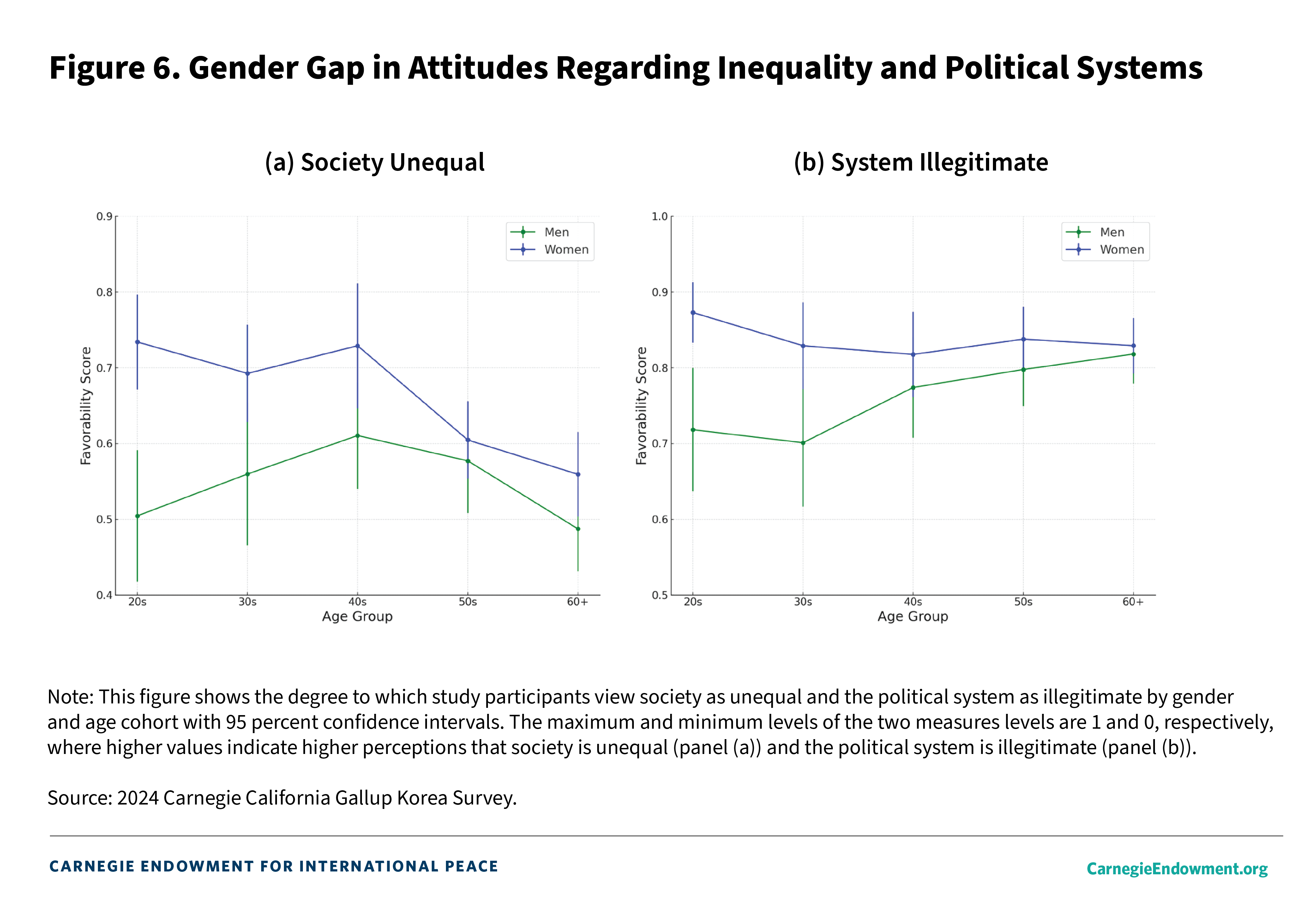

It is hardly shocking that young women are more likely to see society as unequal—by a margin of 5 percentage points—and to view the political system as flawed—by 4 percentage points—compared to their male counterparts (see Figures 6[a] and [b], respectively).10 Given their lived experiences in a country rated poorly with regards to gender outcomes, it would be more surprising if they did not. But of note, despite improvements in women’s economic opportunities, education attainment, health, and political leadership over time, the gender differences in both perceptions of societal inequality and a problematic political system are only visible (that is, statistically meaningful) among those in their 20s and 30s.

When we look at the connection between perceptions of system illegitimacy and attitudes toward gender-related policies and sexism among young men and women, a clear pattern emerges: deep skepticism about the political system among men tends to coincide with lower support for policies designed to promote gender equality (see Figure A2 in Annex 1). In contrast, among women, perceptions of system illegitimacy are associated with lower hostile and modern sexism and increased support for policies reducing gender inequality (see Figure A2 in Annex 1).

Patterns look different when we shift the focus to perceptions of societal inequality. Both young men and women who see inequality as a serious issue are less likely to embrace modern sexism, which is a sexism measure that assesses whether someone downplays or outright denies the existence of gender discrimination (see Figure 7) and is inclined to support policies that enhance gender equality (see Figure A2 in Annex 1). In other words, acknowledgment that society is unequal translates to greater support for measures aimed at addressing gender inequality. This raises an intriguing question: could increasing awareness of gender inequality help move young men toward more egalitarian views?

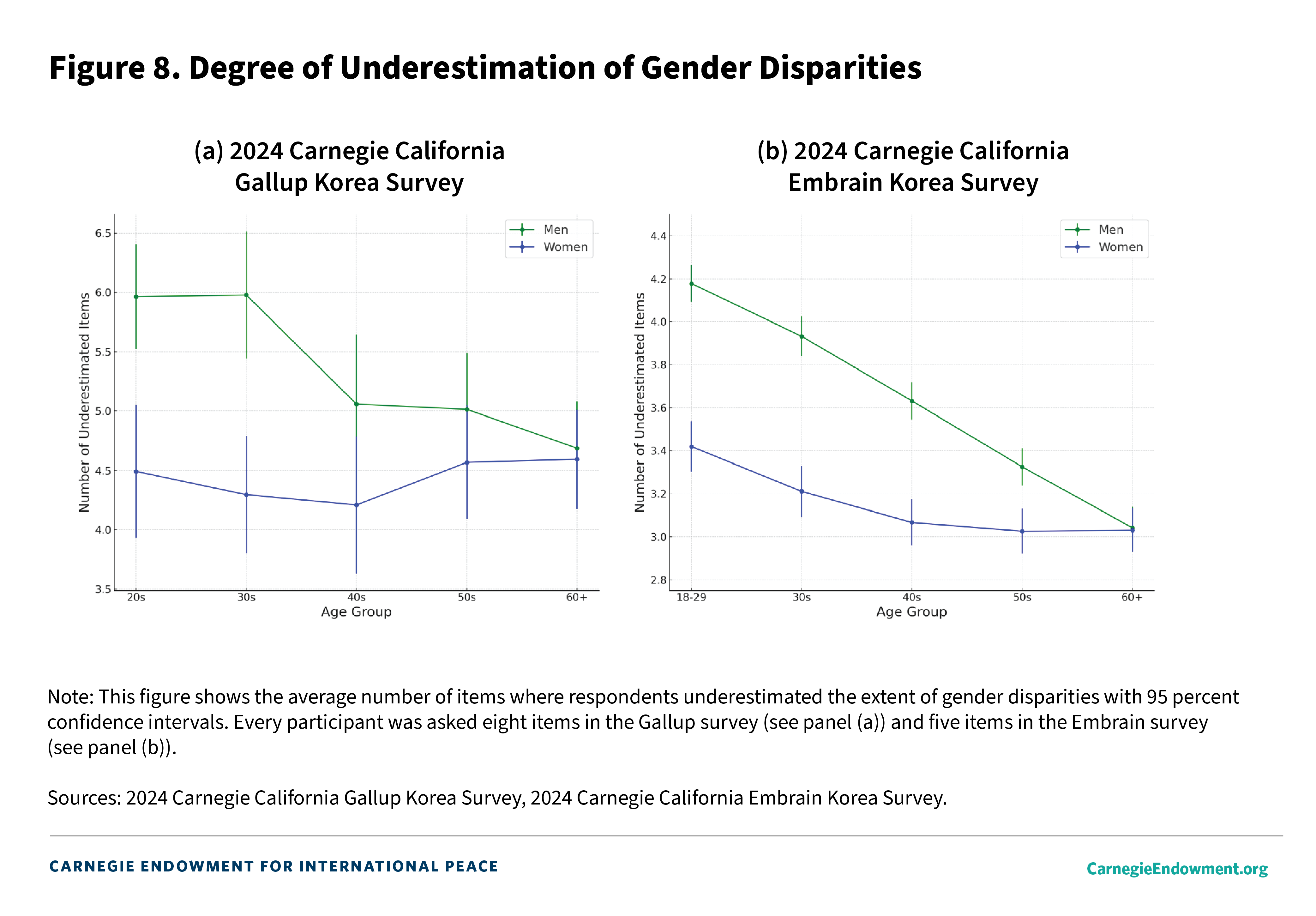

The observed resistance to gender equality policies among young men is associated with a lack of awareness regarding the extent of gender disparities (see Figure 9). Younger men are more likely to underestimate gender discrimination compared to their female and older male counterparts. When asked eight questions regarding gender disparities in economic, political, and educational spheres (see Figure 8[a]), young men in their 20s demonstrated the highest level of underestimation. They misjudged the extent of gender inequality in nearly 75 percent of the items (5.94 out of 10).11 Among men, there is an inverse relationship between age and awareness, with older men in the 60 and above age cohort exhibiting the greatest recognition of gender disparities, underestimating them for 4.69 items. However, this pattern does not hold among women; both young women in their 20s and older women aged 60 and above underestimate disparities at similar levels (around 4.5 items). Moreover, there is only a divide in perceptions regarding gender disparities among those in their 20s, 30s, and 40s.

These patterns, with the largest gender disparity being among those in their 20s and 30s, were largely replicated in the 2024 Carnegie California Embrain Korea Survey (see Figure 8[b]). Unlike what we observed in the Gallup sample, in the Embrain sample, a slight negative relationship between age and awareness is observed among women as well. However, this inverse relationship is much more pronounced among men. As observed in the Gallup sample, the gender gap clearly diminishes as age cohorts progress. These findings suggest that younger men are particularly prone to downplaying gender disparities, distinguishing them from both their female peers and older male counterparts.

When provided with corrective information about the actual extent of gender disparities, young women who initially underestimated these inequalities consistently show decreased modern sexism, which is a metric that, in part, gauges the extent to which individuals deny the existence of discrimination against women, as well as increased support for policies and programs promoting gender equality in the public and private sector, and for policies related to military service that do not favor men (see the estimates for “1. Public Institutions Policies” through “3. Military Policies” and “7. Modern Sexism” in Figure 9).12 Effect sizes range from 5 to 10 percentage points. However, the same information has no measurable positive impact on the policy preferences of young men. In other words, efforts to highlight realities regarding gender gaps in the economic, political, and social spheres worsen the divide. These results suggest that intensive efforts to shine a light on gender inequality in South Korea will likely not help bridge the divide.

When asked why South Korea ranks so poorly on gender equality measures in the 2024 Carnegie California Embrain Korea Survey, many open-ended responses from young men in their 20s and 30s suggest that addressing misperceptions in the degree of gender inequality will be quite difficult. While some young men acknowledged issues related to gender discrimination and traditional norms, and many admitted uncertainty, a striking number of responses suggest that trying to raise awareness about gender equality through data and statistics regarding unequal outcomes is a losing battle. Rather than shifting opinions, these efforts are more likely to be met with skepticism, dismissal, or outright rejection.

Many young men dismiss measures addressing gender inequality as unreliable and question the validity of the rankings, attributing them to “incorrect counting,” “errors in the survey,” “trashy surveys,” and “fabricated statistics.” Others, while not disputing the statistics outright, argue that these figures merely reflect “discrimination in the past” or “from older generations.” In their view, gender inequality is not a pressing issue for the current generation, and disparities in wages and leadership representation will naturally resolve as older generations retire.

Another subset of respondents shifts the blame to women themselves, attributing lower wages and promotion rates to “anti-male hatred” fueled by the feminist movement, “feminist quotas,” “whining women,” and accusations that Korean women are “intentionally ruining things” and initiating “gender conflict problems.”

Another recurring theme in these responses revolves around perceptions of innate differences in ability and work ethic. Many young men cite “differences in ability between men and women,” claim that “[women’s] abilities are not up to par,” and argue that “young women are not making an effort.” Some assert that women “prefer work that is convenient and comfortable” or that there is a “phenomenon of avoiding hard work.” These responses showcase how tricky it will be to bridge existing ideological fault lines between young men and women today.

One frequently cited explanation for rising gender hostilities concerns the sources and environments through which individuals consume information. Online spaces, where misinformation is common, are often mentioned in this context. Kim, for instance, argues that misogynistic discourses in male-dominated online spaces in South Korea, such as the online forum Ilbe, reinforce gender stereotypes and justify gender discrimination. According to the 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey, most young men (56.1 percent) report engaging with such male-dominated online spaces. And as expected, among young men, use of these spaces is associated with increased hostile and modern sexism, and less support for nearly all policies aimed at advancing gender equality (see Figures A3 and A4 in Annex 1). However, it is worth emphasizing that these associations are not causal relationships. It is also plausible that men who already hold more sexist views may be more likely to seek out and engage in these online communities. Nevertheless, given the strong associations between the use of male-dominated online communities and gender hostility, further examination of the potential deleterious effects of these communities on the growing gender divide is necessary.

Demographic shifts and evolving marital dynamics, particularly the increasing number of women opting out of marriage, may be contributing to the rise of anti-feminist backlash. In 2024, You’s study identified the “marriage squeeze”—a phenomenon in which men outnumber women in the marriage market—as a key factor driving opposition to gender-equality policies. You points to three key forces behind this imbalance in South Korea. First, for decades, the government pursued anti-natalist policies to curb population growth. Second, deep-rooted cultural preferences for sons led to a gender imbalance. Third, faced with economic pressures and shifting social expectations, young women today are increasingly choosing to opt out of marriage at higher rates than men. This shift has fueled the rise of the 4B movement, where women reject marriage, childbearing, dating, and even relationships with men altogether—a movement that has spread beyond South Korea, including to the United States.

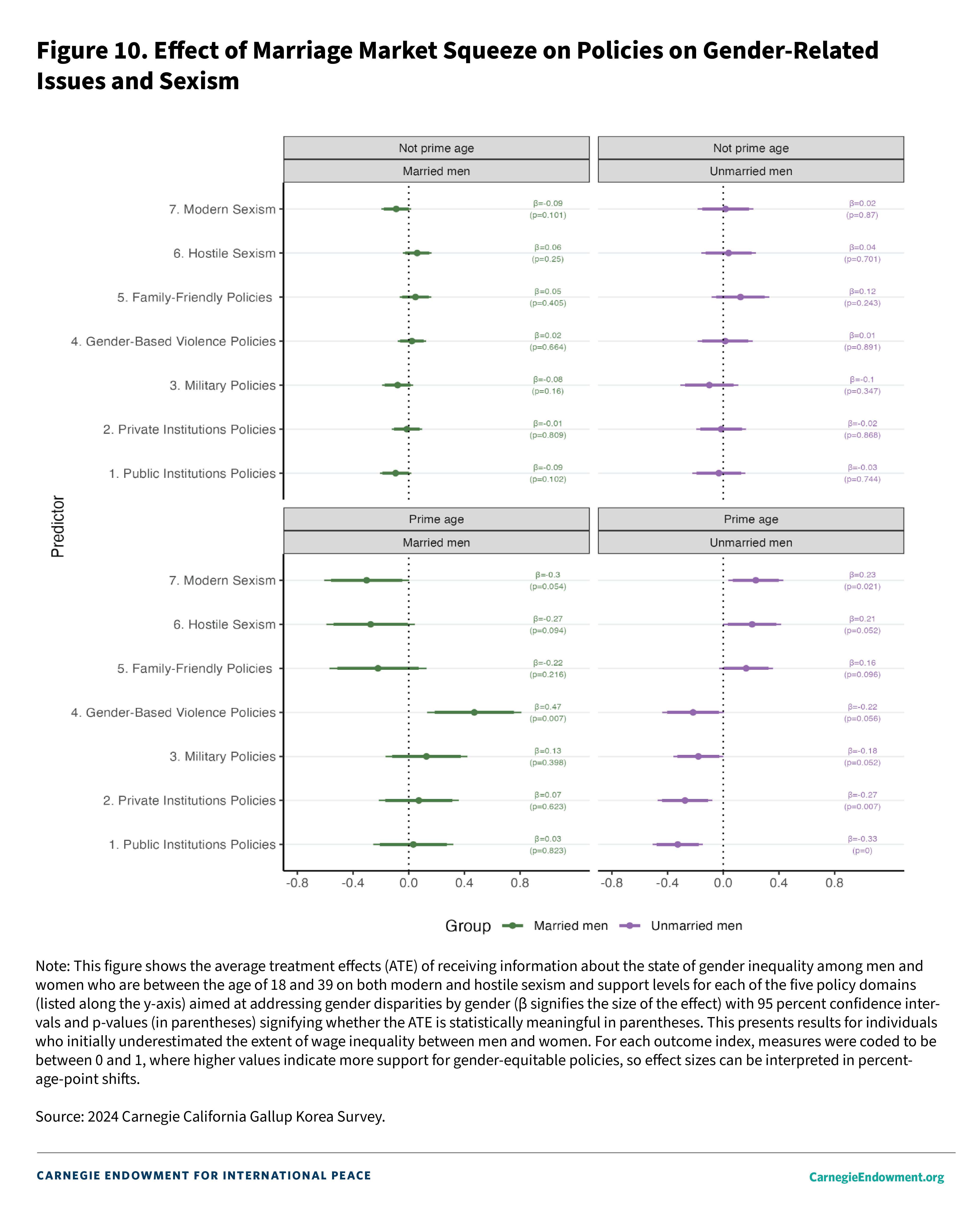

Replicating You’s experimental research design and applying it to a broader range of policy outcomes, the new results from the Gallup survey corroborate her key conclusion. The growing disparity in marriage preferences between women and men in a society with more men than women is leading to an anti-feminist backlash. Beyond intensifying resentment toward women in South Korea, it’s galvanizing opposition against policies advancing gender equality, including efforts to increase women’s representation in politics and business, as well as measures to combat gender-based violence. We highlight some of these findings below.

First, making the marriage squeeze more salient causes unmarried men in their prime marital years to exhibit more resistance to women’s empowerment, as shown in the bottom left panel of Figure 10. Stunningly, simply telling individuals that women are much less likely to want to marry compared to men makes men less willing to support measures promoting gender equality. This effect is driven by unmarried men in their prime marital years (see the bottom right panel).13 There is no comparable effect among married men, who are personally unaffected by the marriage squeeze (see the bottom left panel) or older men, regardless of marital status (see the top panels). These findings suggest that perceptions of marriage dynamics play a critical role in shaping single young men’s opposition to gender-equality initiatives.

It is striking how widespread this backlash is. It is not confined to just one issue—it cuts across almost every domain we examined (see the negative average treatment effect [ATE] estimates for outcomes “1. Public Institutions Policies” through “4. Gender-Based Violence Policies,” that is, declines in support for these policies) in the bottom right panel (unmarried men in their prime marital age) of Figure 10). Unmarried men in their prime marital years are more resistant to having more women in government and political leadership. They push back against greater female representation in private industry. They prefer hiring and promotion policies that give preference to those with a military service background—policies that, by design, favor men since all men in South Korea are required to serve, while women are not. And they are even less supportive of measures designed to prevent gender-based violence, both online and offline. The pattern is clear: resistance to women’s empowerment stemming from feeling squeezed in the marriage market is not isolated—it is systemic.

The only policy domain in which the salience of the marriage market squeeze led to an increase in support were related to family-friendly policies (see the positive ATE estimate for “5. Family-Friendly Policies” (that is, increased support for these policies) in the bottom right panel of Figure 10). This is perhaps unsurprising, given that there are high levels of support for family-friendly policies, regardless of gender (see Figure 2[e] and Figure 3), and many individuals see the high cost of raising children as a key reason for avoiding marriage in the first place. In other words, young men view family-friendly policies that provide subsidies that reduce childcare costs and extend family leave to men as aligned with their interests.

Second, the response to the marriage squeeze extends beyond resistance to gender-equality policies; it also exacerbates antagonistic attitudes toward women among unmarried men. When informed about the disparity in marriage preferences between men and women, which disadvantages men, unmarried men exhibit increased levels of hostile sexism and modern sexism (see the positive ATE estimates for “6. Hostile Sexism” and “7. Modern Sexism” (that is, increased sexism) in the bottom right panel of Figure 11). No such shift is observed among married men in their prime age or men that are not in their prime age for marriage (see the panels in the top row [men in their prime marital age] and the bottom left [married men in their prime marital age]).

The negative effect of the marriage market squeeze on gender attitudes is particularly worrisome as the salience of the squeeze is likely to worsen. Young women are much less likely to express interest in getting married and having children than young men. According to the 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey, among unmarried young women in their 20s and 30s, just 8 percent say having marriage is extremely or very important to them and 11 percent say the same about having children. This stands in stark contrast to single young men in their 20s and 30s, among whom 26 percent consider marriage extremely or very important to them and 28 percent hold similar views on having children.

South Korea may be caught in a self-reinforcing, negative feedback loop—one where the demographic realities and shifting social attitudes feed off each other in ways that deepen the very problems they create. As more men perceive marriage as increasingly unattainable due to demographic gender imbalances and women’s growing reluctance to marry, the political and ideological landscape tilts further toward conservatism, reinforcing sexism and resistance to gender equality. But these very attitudes likely make marriage even less appealing to women, which in turn fuels even more backlash among men. It is a vicious cycle—one that is hard to break and has profound political and social implications.

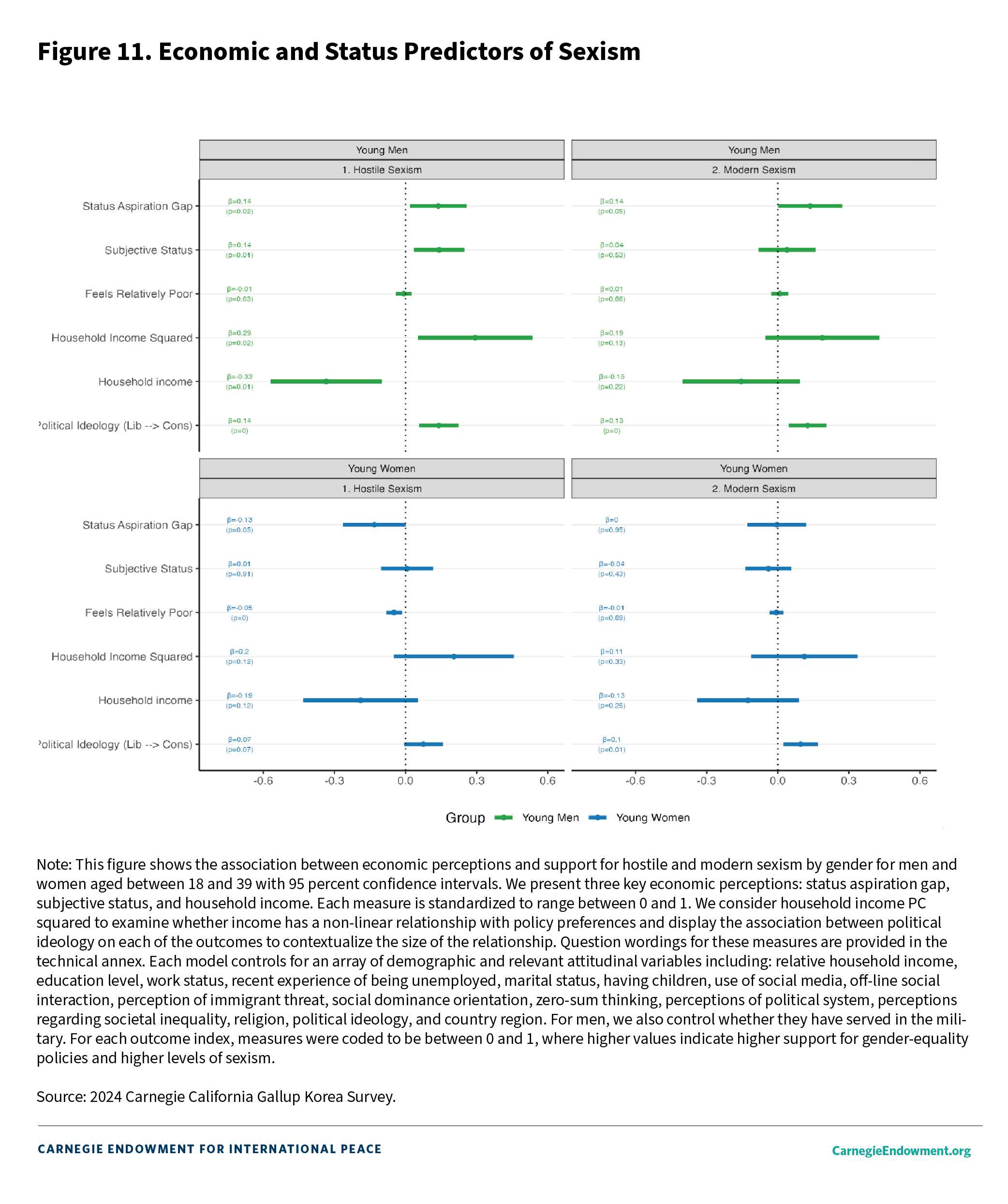

Even when accounting for an array of demographic characteristics, belief systems, and social and political attitudes, economic anxiety is associated with negative gender views. Namely, among young men, having a higher household income is associated with lower hostile sexism (see the “Household Income” row in the top panel of Figure 11) and greater support for policy measures to increase gender representation in corporate leadership to increase gender equality (see the “Household Income” row in the top panel of Figure A5 in Annex 1).

While higher income is initially associated with more progressive gender views, this association weakens at upper income levels—suggesting that beyond a certain point, additional wealth does little to improve, and may even hinder, support for gender equality (see the negative estimate in the “Household Income Squared” row in the top panel of Figure 11). Indeed, young men who report a higher subjective status tend to be slightly less supportive of gender-equality policies and exhibit higher levels of hostile sexism. In other words, it is not clear that simply improving people’s economic situation and subjective status is going to always be associated with improvements in the gender divide.

In fact, improved perceived status could correspond with a negative change in gender-related attitudes if people’s actual status does not keep up with their aspired status. The status aspiration gap—the perceived distance between where young men are and where they believe they should be—is a strong negative predictor of gender egalitarian views. Young men with a wider aspiration gap are significantly less supportive of policies designed to promote gender equity in both the public and private sectors and shifts in military veteran policies in a way that does not lead to advantaging men (see the “Status Aspiration Gap” row in the top panel of Figure A5 in Annex 1). They also exhibit substantially higher levels of both hostile and modern sexism. Moving from no status aspiration gap to the maximum status aspiration gap, we observed in our sample, is associated with a 14 percentage-point increase in both hostile and modern sexism (see the “Status Aspiration Gap” row in the top panel of Figure 11). The size of the association is comparable to political ideology, which is a strong predictor of policy preferences and sexist attitudes. This pattern aligns with research done by Healy, Kosec, and Mo, who pointed out the power of aspiration gaps to foment political disaffection.

The one exception comes when examining family-friendly policies (see the “Status Aspiration Gap” row in the top panel of Figure A5 in Annex 1). In this case, larger gaps in status aspirations are associated with greater support for policies designed to alleviate the burdens on families and family planning. However, it is worth noting that this is the one policy area where young men, on average, are notably supportive, and there is no evidence of a large gender divide. Consequently, while the positive association may appear encouraging, it does not offer a fruitful avenue for bridging the gender divide.

A suggestive, though similar pattern emerges when looking at relative economic standing. Young men who perceive their household as poorer relative to those around them are also less likely to support policies to reduce gender-based violence (see the “Relatively Poor” row in the top panel of Figure A5 in Annex 1). This pattern aligns with recent research by Kosec and Mo, which underscores how perceptions of relative poverty influence support for programs designed to assist the most marginalized and vulnerable populations. These findings are also consistent with that of Kosec, Mo, You, and Boittin, which highlights how perceptions of relative deprivation can foster regressive gender norms. Past research on relative deprivation and patterns in the 2024 Carnegie California Gallup Korea Survey suggest that the perception of falling behind—whether in comparison to others or in relation to one’s own aspirations—matters in addition to actual economic status in shaping resistance to gender-equality initiatives. When young men perceive themselves as losing ground relative to others, they may compare themselves to or relative to where they feel they need to be, they become less inclined to support some policies aimed at fostering greater gender balance in society.

For young women, the story is a bit different. Those with a larger status aspiration gap tend to exhibit less hostile sexism (see the bottom panel of Figure 11), but such a gap is only associated with support for polices related to making Korean society more family friendly (see the bottom panel of Figure A5 in Annex 1). Feeling relatively poor is associated with less hostile sexism attitudes, and it is predictive of increased support for policies to advance the status of women in four of the five examined policy domains. This may be driven by the fact that women who feel relatively poor feel more of a pressing need for policies to assist women.

South Korea’s gender divide has become a defining political and social fault line, shaping electoral outcomes, policy debates, and even the country’s demographic trajectory. The growing anti-feminist backlash among young men—driven in part by perceptions that women are not discriminated against, economic anxieties, a widening status aspiration gap, and changing marriage dynamics—has intensified political polarization and now threatens to reverse hard-won progress on gender equality. The 2024 Carnegie California Gallup and Embrain Korea Surveys highlight the extent to which young men and women are diverging—not only in their policy preferences but in their fundamental perceptions of fairness, opportunity, and social progress.

This growing divide is not just a Korean phenomenon. Similar patterns are evident in other advanced democracies, including Germany and the United States, where young men and women are diverging in ideological directions. The political consequences of this divide may be profound. As gender becomes an increasingly salient axis of polarization, traditional party coalitions may realign, and policymaking could undergo significant changes, with some harnessing anti-feminist sentiments to advance their political agendas.

Addressing these trends will require more than just presenting evidence of persistent gender disparities; if anything, such efforts risk exacerbating the gender divide as women feel more urgency to advance policies that address these disparities. Instead, policymakers must focus on addressing the deeper economic and social insecurities that drive resistance to gender equality. This includes paying attention to demographic patterns and views on marriages, which affect marital dynamics, as well as, addressing the growing sense of disillusionment among young men who feel relatively deprived and left behind amid worsening economic and social inequalities, while ensuring that gender equity initiatives are not perceived as coming at men’s expense in a zero-sum struggle.

South Korea’s experience serves as both a warning and a lesson for other nations grappling with similar tensions. If left unchecked, the gender divide could deepen political dysfunction, weaken democratic resilience, and exacerbate demographic and economic challenges. The task ahead is not just to bridge ideological divides, but to build a society in which gender equality is not seen as a threat—but as a necessary foundation for long-term prosperity and stability.

This project has been supported by donations from the Korea Foundation and the NC Cultural Foundation.

Click here to see full technical results. (PDF)

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

South Korea has emerged as a major weapon exporter. But its relationship with Europe will depend on more than that.

Chung Min Lee

Lessons from Korea’s political right.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares

Emerging AI technologies are entangling with a crisis in democracy.

Rachel George, Ian Klaus

Facing acute threats, states in Northeastern Europe are pioneering a pragmatic model of defense-industrial cooperation that offers lessons for managing transatlantic dependencies in an era of uncertainty.

Sophia Besch, Erik Brown, Rafaela Uzan

Regional disparities in investment, labor markets, and government transparency mean that regional development will be a key feature of Ukraine’s postwar future.

Mariya Levonova, Balázs Jarábik