A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

Source: Getty

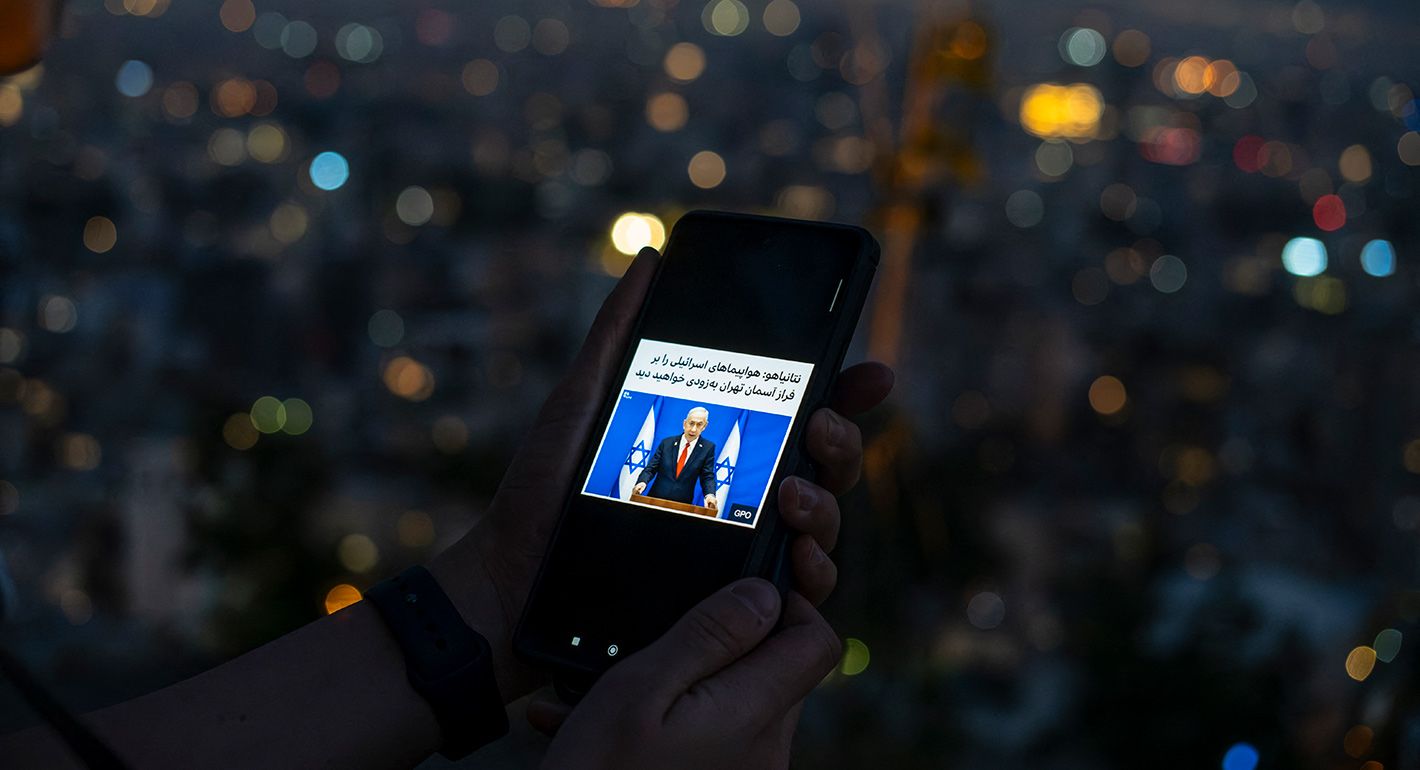

The war signaled critical challenges in the growing gap between the sophistication of AI deception and analysts’ ability to detect it, heralding a frightening new phase in global conflict.

On June 23, 2025, WITNESS received a WhatsApp video showing clouds of smoke billowing from Evin prison in Tajrish, Iran. Filmed from a nearby apartment, the communication carried a stark message: “They are trying to open Evin.” The infamous prison—a site of torture, killing, and confinement of dissidents, journalists, and activists—had been bombed. Israeli officials deemed the strike “symbolic,” a gesture against the Islamic Republic’s repression. For many Iranians, shattering the gates of Evin seemed to be a resonant symbol of hope for the freedom of the nation’s best and brightest long held behind its walls.

On social media, Israel tried to capitalize on this development. Its foreign minister posted another clip showing Evin’s entrance gates being blown apart in an apparent surgical strike. He boasted on X (formerly Twitter), “¡Viva la libertad, carajo!” (“Long live freedom, damn it!”). But unlike the first video, the Israeli footage was likely fake.

Forensic analysis of the Israeli clip suggests that it was likely created using artificial intelligence (AI). For example, it contained still images of the Evin gates found in an article published in 2021; these images could have been manipulated by AI tools. These findings were corroborated by the DeepfakesRapid Response Force, a rapid response mechanism for evaluating deceptive AI run globally by WITNESS.1

Although the Israeli foreign minister’s video depicted a clean precision strike, in reality, the attack on Evin was far from that; Israel’s bombs resulted in significant collateral damage. Human rights groups and other observers reported on the deaths of residents and commuters near the prison, casualties among family members who were visiting or posting bail, and serious injuries and deaths among the prisoners Israel claimed it was freeing. Advocates even reported that surviving prisoners were moved to more harrowing conditions because the prison was destroyed.

The individual who sent us the authentic Evin footage lives in Sattar Khan, a Tehran neighborhood that was hit in the first wave of Israeli strikes when the Iran-Israel war started on June 13. His experience illustrates how ordinary Iranians were forced to navigate a disorienting landscape of airstrikes, blackouts, and conflicting narratives about what was happening around them during the conflict.

As the war intensified and Israel called for evacuations, some Iranians left, while others, like the Sattar Khan resident, stayed. By June 18, much of Iran including Tehran was under a near-total internet blackout perpetuated by Iran itself. The regime has frequently imposed internet shutdowns, especially during protests, to control the flow of information and communication to prevent civilian uprisings.

What makes this situation different from prior wars is that there has been a significant increase in the use of AI-generated content.

After some connectivity resumed on June 21, our contact in Sattar Khan replied to our WhatsApp messages, saying, “Everything is good. Truthfully Israel has nothing to do with us. Only the night before last, they came to bomb a local Basij [state paramilitary group] quarter close by, but accidentally hit someone’s home next door. Luckily no one was home. Don’t worry, if these akhoonds [the Persian word for the clerics] don’t kill us, Israel definitely won’t.”

But this was not true. Our contact in Sattar Khan was far less safe than he believed. Only days before, a twenty-three-year-old poet named Parnia Abbasi was killed alongside her family in the same neighborhood by Israeli strikes. Across Iran, Israeli strikes killed or injured a sizable number of Iranian civilians. The U.S.-based human rights organization HRANA (Human Rights Activists in Iran) estimated that at least 417 civilians had been killed and 2,072 injured as of June 25. While our contact may have believed that Israel had “nothing to do” with him, the reality was that the risks were far more serious than he knew.

What explains why he lacked access to objective information? During the blackout, Iranian citizens were forced to rely almost exclusively on official state news, which downplayed the devastation of the bombings, proffered the belief that Israel’s attacks were ineffective, and pushed residents to refrain from evacuating and go ahead with business as usual. When internet connectivity was restored, Iranians were subject to a different form of information manipulation—one emanating from Israel that framed Israel as only conducting “precision strikes” and painted the war as being waged in the interests of the Iranian people. Neither perspective was accurate, and both left the Iranian public with a false sense of security amid the intensifying violence.

This chilling disconnect between reality and narratives online and in the media has increasingly become a feature of modern war. In the Iranian context, pervasive deployment of propaganda and synthetic media has been magnified by the country’s authoritarian internet environment. The result is that citizens are often unable to verify or cross-check information fed to them by state or conflict actors. They are forced to battle through both the absence of information because of shutdowns and the presence of information pollution because of propaganda efforts occurring before, during, and after blackouts.

What makes this situation different from prior wars is that there has been a significant increase in the use of AI-generated content. While other conflicts, including those in Armenia, Ukraine, and Gaza, have seen copious recycled images, fake live streams, and excerpted computer game takes, AI-generated content related to the Iran-Israel conflict has taken disinformation to an industrial level. Supporters of Israel have shared synthetic videos of pro-Israel protests in Tehran, making the false claim that they showed mounting dissent against the Iranian regime. Meanwhile, Iran supporters have circulated AI-generated videos of missile strikes on Tel Aviv, some carrying Google Veo watermarks because the uploaders likely forgot about these embedded flags of inauthenticity. AI-generated images of Israeli F-35 planes allegedly shot down over Iran were even broadcast on Iranian state television. The proliferation of this kind of content at such a fast pace was unprecedented. The Evin blast footage, for example, found its way onto social media within an hour of the incident and was reported and shared by credible news outlets such as Sky News and BBC immediately. False narratives have come to dominate the wartime information ecosystem.

In Iran, people have long known to second-guess what they see from the state. But the evolution in synthetic media requires adding a new exhausting layer of distrust to the information ecosystem as people further question whether what they are seeing is real. Moreover, the scale and scope of AI-enhanced rage-baiting, engagement-farming propaganda, and deliberate deception represent just the tip of the iceberg. Realistic AI videos with synchronized audio only emerged months ago, but the quality and ease of customization is rapidly improving, particularly as such tools become widely available through mainstream consumer platforms.

These dynamics have implications for every stage of conflict and conflict prevention. Previous research from WITNESS has shown how wartime contexts are characterized by a competition for control of the narrative by conflict participants, as well as extensive attempts to monetize surging global attention. Consequential decisions are taken based on the information available, and fragile peace processes can be easily disrupted by rapidly spread rumors. Following the Myanmar coup in 2021 and at the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine in 2022, there were early attempts to use falsified live streams for attention and funds. In Gaza, participatory campaigning, where activists share AI-generated content to gain attention and assert identity, has emerged. One notable example was the slogan “All Eyes on Rafah”—an AI-generated image showing an imagined desert and tent camp for displaced Palestinians that was shared more than 47 million times following an Israeli airstrike against the southern Gaza city of Rafah in May 2024. The image was obviously synthetic and used for campaigning; however, some analysts criticized it for not showing “the true extent of what’s really happening on the ground”—depicting only an empty tent city with no visible human presence or war damage. The sophistication and verisimilitude of these approaches are increasing, while their cost is decreasing.

However, the world is not helpless to confront these challenges. There are technologies that can detect deceptive AI and flag the presence of both AI and authentic content. One set of detection tools works after the fact and is most often deployed when users do not have any information on how the content was created but suspect malicious or deceptive AI usage. These tools deploy diverse detection techniques to spot statistical patterns or inconsistencies in content that could indicate the use of AI. For example, some detection techniques identify AI manipulation by looking for discrepancies between a video’s audio and visual elements. Other techniques compare potentially synthetic content with verified samples featuring the public figure in question or look for inconsistencies in synthetic outputs.

Another set of complementary approaches—we call them provenance and authenticity infrastructure and standards—seek to document the origins and history of particular data by adding a label or watermark, embedding metadata, or using fingerprinting. Tools such as Google’s SynthID and technical standards including the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) framework can provide useful context and signals across a range of AI products as well as authentic, non-AI media.

Post hoc detection approaches are not straightforward. These detection tools may only work to detect a single format of falsified content, and most do not work well on low-quality social media content. Their confidence scores—say, a 73 percent likelihood—are hard to evaluate if users do not know how reliable the underlying technology is or whether the tool is right to test for the manipulation technique that was used to generate the forgery. Meanwhile, the algorithm for detecting how something was manipulated with AI may not spot a manual edit and will not identify so-called shallowfake content (miscontextualized or lightly edited videos and images) that is also pervasive.

Sophisticated detection methods can yield conflicting findings, leaving it up to journalists, human rights defenders, and civilians in conflict zones to navigate the fog of war without a clear signal of what is real.

Take, for example, a clip circulated by Iranian state media on June 15 purportedly showing an Israeli strike on Borhan Street in the Tajrish neighborhood of Tehran. The video showed a scene of carnage—a bombed out six-story apartment building, damaged cars strewn about, and ruptured water pipes—and made global headlines. But some viewers quickly questioned whether the footage had been manipulated. The strike on that neighborhood and that street were confirmed, as well as the number of civilian victims injured and killed. But when different analysts examined the video’s authenticity, the results were mixed. Some advanced AI detection tools within the Deepfakes Rapid Response Force found evidence of generative AI use in the video. The force’s experts also pointed to several physical inconsistencies in the video, which further suggested AI manipulation. But other open source intelligence investigators and independent analysts, including BBC Verify and Professor Hany Farid, found no conclusive signs of fakery. The video, a recording of a CCTV screen, lacked metadata and showed physical inconsistencies. Yet, despite the uncertainty around the video, it was quickly treated as breaking news. This unresolved case demonstrates how even sophisticated detection methods can yield conflicting findings, leaving it up to journalists, human rights defenders, and civilians in conflict zones to navigate the fog of war without a clear signal of what is real.

Despite their flaws, these detection tools are still necessary for identifying deceptive AI usage and are often not available to people in the midst of conflict who need them most. When they are available, they often fail in their purpose because they are not designed for global populations, languages, and media formats, or because they do not provide an answer that is easily comprehensible to a journalist, a non-expert, or a skeptical public. Detection that works for some, but not most, cases risks contributing to confusion, not resolving it. In many cases, false claims about AI manipulation have been used to discredit real footage, and claims that something is made with AI have been used to dismiss compromising leaks.

As the world continues to experience instability and war, there is a growing gap between society’s ability to detect increasingly realistic synthetic content and the efficacy of detection tools that work amid conflict and crisis. Tools to trace and detect AI-generated content must be made available and usable by those on the front lines—WITNESS identifies some steps on how to do this in the recent TRIED framework for effective detection globally. When it comes to provenance tools, building them with repressive environments such as Iran in mind will be critical. It is important to ensure that tools work effectively for people in these contexts and that they do not simultaneously increase risk to users by incorporating design features that abet governments that want more tools to surveil and suppress dissent.

For example, when it comes to designing tools that show embedded metadata on the use of AI, it has become clear that tying identity to media production would be a boon to repressive governments that already seek to suppress speech. While it might help catch malicious actors, it would be a welcome backdoor for tracking dissidents, satirists, and ordinary citizens through their use of AI tools. These tools—if they are to be usable globally and in high-risk contexts such as Iran—should not tie media creation to individual identity. Instead, they should solely focus on producing information on the nature of the content and how AI and human inputs mixed in making a video. Embedding human rights concerns and attention to repressive contexts from the start when designing these infrastructures for increased trust in an AI age is critical.

Although the Iran-Israel conflict has entered a fragile ceasefire, the war over reality itself continues.

None of this will be viable unless regulation and other commitments ensure that tech companies across the AI and media pipeline, including models, developers, tools, and platforms, share the burden by embedding provenance responsibly, facilitating globally effective detection, flagging materially deceptive manipulated content, and doubling down on protecting users in high-risk regions.

During the so-called twelve-day war, Iranians trapped between Israeli airstrikes and the Islamic Republic’s repression struggled to know who or what to protect against. Our contact in Sattar Khan, who once told us Israel would never harm him, later sent us images of smoke over Evin prison, now unsure what to believe or what to fear. And when a video of a bombing on Tajrish’s Borhan Street surfaced, even advanced detection tools and expert investigators could not agree on whether it was authentic or AI-generated. Although the conflict has entered a fragile ceasefire, the war over reality itself continues.

With special thanks to Zuzanna Wojciak who helps run the WITNESS Deepfakes Rapid Response Force (DRRF) and provided valuable review of this piece. Additional thanks to the members of DRRF that contributed to the analysis of the deepfakes referenced in this piece.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

Implementing Phase 2 of Trump’s plan for the territory only makes sense if all in Phase 1 is implemented.

Yezid Sayigh

Fifteen years after the Arab uprisings, a new generation is mobilizing behind an inclusive growth model, and has the technical savvy to lead an economic transformation that works for all.

Jihad Azour

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein