How significant are statements by senior U.S. officials about supporting democracy abroad in the context of a foreign policy led by a president focused on near-term transactional interests?

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

Source: Getty

Emerging AI technologies are entangling with a crisis in democracy.

Emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are entangling with a crisis in democracy. Although AI technologies bring a host of risks related to applying technology to politics, they can also improve representative politics, citizen participation in democracy, and effective governance. These entanglements present a complicated landscape.

The imperative to mitigate AI’s harms and leverage its benefits for democracy could not come at a more critical time. Recent V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) scores show that the level of democracy enjoyed by the average person in the world in 2024 had fallen to 1985 levels.1 Last year, for the first time in twenty years, the world had fewer democracies (eighty-eight) than autocracies (ninety-one).2 Since 2009, recent metrics found that the share of the world’s population living in autocratizing countries, totaling almost 40 percent of the global population, overshadowed the share living in democratizing countries which host only about 5 percent.3 The decline is particularly stark in Eastern Europe and South and Central Asia, but touches all world regions.

The coming year will test democracy’s future. Experts predict a vanguard year for technology, with the global agentic AI market expected to triple,4 demand for chips to support AI data centers rising sharply,5 and AI moving from experimentation to the “center of operations” for many firms.6 Meanwhile, AI’s impacts on the political space remain uncertain, with many important elections coming up this year. Uganda’s upcoming January general election will signal the country’s potential to counter deepening authoritarianism in East Africa, while Bangladesh’s February national elections will test the potential to reverse current trends in democratic erosion. March and October elections in Colombia and Brazil will test the potential for democratic gains in major Latin American economies, while Israel’s upcoming parliamentary elections will test institutions facing constitutional strain. Meanwhile, in the United States, November state-level midterm elections mark a key moment for the democracy facing political polarization, including a key upcoming contest in the country’s largest state economy, California. Taken together, these contests illustrate a broader global crossroads: whether democratic backsliding continues to harden or whether democracies build institutional resilience.

Democracy advocates warn that AI amplifies existing threats in the digital information environment, including misinformation, polarization, and repression. When we asked Californians in the summer of 2025 about their views on AI’s role in voting and elections, only 8 percent reported being “very confident” in being able to tell the difference between real and fake content online, with 57 percent reporting that they are “very concerned” about the influence of deepfakes and other AI-generated content in elections.7 Many applications of AI technologies to politics and civic life present opportunities for democratic institutions alongside risks for repression and misuse—echoing and amplifying some of the effects of past digital transformations. Digital progress has long been Janus-faced in its offer to both strengthen and weaken democracy,8 but it takes on new contours with the unprecedented power of AI to collect and process data. Beyond that, the rise of generative AI, which creates new, original content from existing data, and the emergence of agentic AI, which can act autonomously toward goals, both present distinct risks and benefits for democracy as AI increasingly automates tasks and shapes its operating environment. Work to address these challenges and opportunities requires a broad understanding of democracy. Not all AI-related activities that are relevant to democracy fall under conventional labels of “democracy work” or related studies, and the rapid pace of technological advancement will require improved translation of AI’s potential and perils more effectively to publics and policymakers.

The last five years have seen remarkable technological progress in the power and potential of AI technology to transform how citizens and government interact. To harness its benefits and manage risks, governments need updated regulations and skills training, but policy responses have historically struggled to keep pace with rapid technological development. As noted in the recent “California Report on Frontier AI Policy,” early design choices and security protocols will shape long-term governance challenges.9 Meanwhile, scholars note a fundamental trade off in AI model development: limited AI systems that are controlled and narrowly built for accuracy (“symbolic AI”) require balancing with messier systems built on high-dimensional data that define generative AI, where errors inevitably occur, with implications for trust and safety.10

Democracies must balance the potential benefits of messier and more powerful AI systems with their unavoidable risks of misinformation, mistrust, and political manipulation.

Democracies must balance the potential benefits of messier and more powerful AI systems with their unavoidable risks of misinformation, mistrust, and political manipulation. At its heart, democracy requires tools and processes for collecting preferences among electorates, areas ripe for transformation with the rise of emergent capabilities such as machine learning, big data, and the introduction of large language models (LLMs). These tools hold potential to transform not only the electoral process but also the aspects through which democracy is developed and delivered, including through campaigns, polling, governance, legislation, justice, human rights, security, and more.

Observers of democracy may view the intersection of the two domains with dismay: On its surface, AI appears thus far to have negligibly fulfilled its promise for safeguarding and renewing democracy, with risks accelerating as regulation lags, leading to limited and inconsistent regulatory patchworks across markets.11 Yet a more dynamic and potentially optimistic picture can be found in the global initiatives and interventions that fall under the broad umbrella of work on AI and democracy. This paper reviews the nature of and maps the landscape of this work, describing some of the critical points of intersection between AI and democracy, relevant risks and opportunities, and the status of different activities working to address them, presenting a taxonomy of prominent issues facing scholars and practitioners working at the intersection.

The potential impacts of AI on democracy are vast, especially when recognizing the multiple definitions of democracy.12 Common understandings of democracy focus on direct and participatory models of governance, with some centered on citizen deliberation and democratic input while others prioritize representative models with a focus on institutional design and reform or on issues such as civic organizing, justice, and the rule of law. Still others spotlight wider socioeconomic and political conditions and outcomes.13

The analysis here draws on interviews with leading technologists, researchers, and practitioners in addition to desk-based research given the fast-moving nature of the relevant fields. The findings represent the areas experts consider to be key intersection points between democracy and AI. Taking a broad view of democracy, there is a vast, and admittedly overwhelming, set of activities that could be considered relevant to the connections between the two domains. The diversity of issues at the intersection, some of which will not fall under conventional “democracy work” labels, indicates the significance of a deeper understanding of potentially relevant efforts that does not exclusively rely on the use of “democracy” terminology.

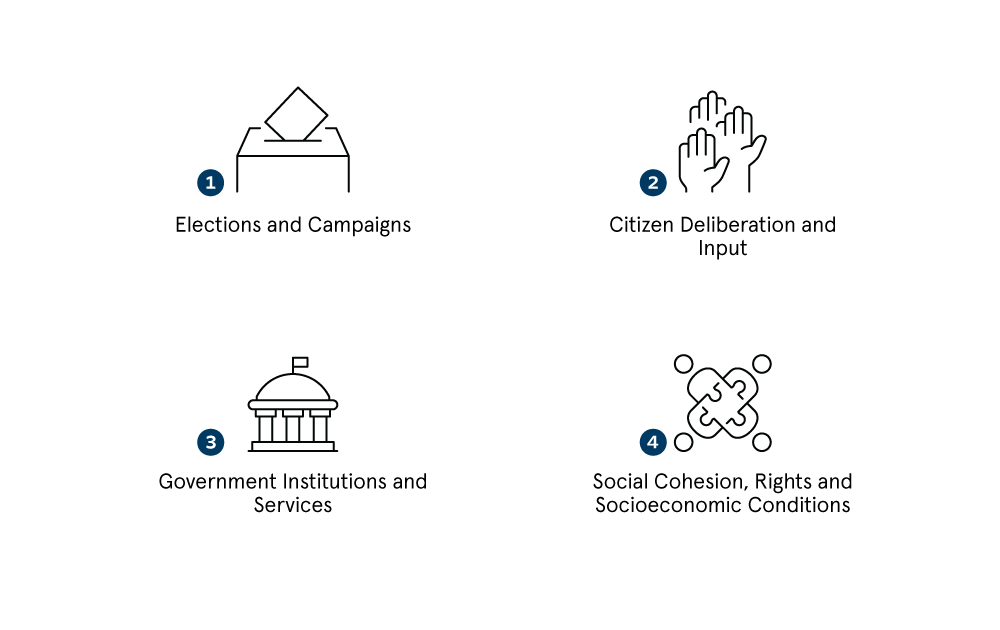

We identify four critical domains around which AI and democracy intersect. Though not exhaustive, this framework highlights some of the main catalytic interactions around developing AI and potential democratic futures and organizes our mapping landscape of ongoing interventions that follows.

One is the intersection of AI technologies with elections and campaigns.

Publics and policymakers alike express rising concern about AI’s potential impact on elections.14 While algorithms have been responsible for shaping the information environment for some time, new AI developments, including generative AI and advanced large language models, present new challenges and opportunities for election integrity and for the wider information ecosystem shaping electoral outcomes.

Some scholars point out that wider structural challenges facing democracies worldwide, such as voter disenfranchisement and election integrity, remain democracy’s most significant threats—an important reminder that it is not technology that on its own undermines elections but rather its interactions with wider political and social environments.15 Some point out that generative AI’s impacts on elections so far have been “overblown,” highlighting that AI’s influence in a hallmark year for global elections in 2024 fell short of fears of widespread damage.16

But risks remain as deepfakes and misinformation threaten to cause more extreme damage in the future, with experts noting that “the genie is loose.”17 As just a few examples, in 2024, a Russian operation using AI and other digital tools reportedly influenced the first round of a Romanian presidential election, leading a court to nullify the initial ballot and to run a new vote.18 And the 2023 elections in Nigeria and the 2024 elections in South Africa both experienced influence from harmful AI-generated content, including both audio and video content aiming to influence election outcomes.19 Similar reports suggest AI is supporting foreign election influence campaigns in South and East Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere.20

The proliferation of deepfakes can have both direct and indirect effects on politics, with a variety of potentially destabilizing impacts on democracy.21 AI’s capacity to amplify misinformation can alter citizens’ “knowledge basis,” what scholarship has deemed a profound foundation for democracy, thereby threatening the fabric of democracy.22 At the same time, AI raises a number of opportunities to support the representativeness and reach of elections and campaigns, for example by supporting interventions aimed at expanding voter registration and turnout, thereby enhancing democracy.23

Another intersection point between AI and democracy relates to AI and citizen deliberation and input.

AI holds the potential to dramatically scale citizen dialogue and consultation, both for the governance of models themselves as well as to facilitate citizen input into government and policy. These tools can expand the depth of citizen consultation, participation, and dialogue—or transform them in ways that might eliminate human bias—to support democratic representation and deliberation. This work also requires efforts to ensure representative participation, scaling, and meaningful democratic use.

An additional intersection relates to that of AI technologies with government institutions and services.

Effective service delivery is linked to the legitimacy and stability of democracy, and governments at national and local levels are increasingly integrating AI technology into their service programs.24 Our mapping identifies important innovations worldwide that reveal where AI can increase the quality and efficiency of government service delivery. Evidence also indicates that AI use by government service providers is growing. A national 2024 Ernst & Young survey found that 64 percent of U.S. federal government employees and 51 percent of state and local government employees reported “using an AI application daily or several times a week,” with reported use in areas including border patrol, drone manufacturing, biometric data collection, and more.25

But the 2025 Carnegie California AI Survey of Californians’ views on government use of AI underscores considerable skepticism even in a state that leads in technology development.26 Despite the United States’ top ranking in the 2024 Government AI Readiness Index,27 which assesses governments’ capacity to integrate AI into public services, the 2025 Carnegie California AI Survey shows that Americans in a leading technology-producing state are concerned about government use of AI.28

Among respondents, few Californians said AI has improved their interactions with government. Only a small number (4 percent) reported that AI “significantly improved” their ability to access public/government services. But significantly more respondents (37 percent) selected that they “don’t know,” revealing an ongoing lack of knowledge and/or uncertainty about how AI’s influence on government services affects them. Respondents were split on whether AI can be used to make government more efficient. A significant number of respondents said that AI is “somewhat important” (36 percent) for improving government efficiency, more than those who said it is “not important” (28 percent), while many said that they “don’t know” (23 percent), signaling public uncertainty about AI technologies and their potential impacts on their interactions with government.

Addressing these trust gaps will be vital, given rising AI use and deep public skepticism, some of which is shaped by unprecedented growth of profit-driven technology firms and their rising influence on the political sphere. Some scholars, such as Bruce Schneier and Nathan Sanders, call for government-funded, publicly accountable AI to help balance these concerns and to safeguard democracy by building stronger trust and safety for government use of AI.29 The concern is especially acute in the United States, where AI is advanced but largely privatized—unlike China’s state-led model or Europe’s blend of investment and regulation—concentrating immense power in a few Silicon Valley firms.

Trust in government use of AI spans multiple issues, without one simple solution. Among challenges, notable gender gaps persist in AI use that will be important to monitor for governance interventions, with women reporting significantly less trust in and uptake of such tools than men, potentially reflecting gendered safety concerns,30 as well as gaps in related training and other socioeconomic differences. Disabled individuals and other marginalized groups also report lower trust.31 Carnegie California found similar gender differences in AI use and trust—even more pronounced than differences based on race or political party. Such a pattern threatens to weaken AI’s democratic potential if participation is uneven across populations.32

Carnegie California found similar gender differences in AI use and trust—even more pronounced than differences based on race or political party.

Improving government use of AI could pay potential dividends for democracy. Enhanced government services can help rebuild the social contract where it is weakened and stave off backsliding. Building on the known benefits of digital/electronic governance (e-governance) for gains such as anti-corruption and access,33 the promise of AI for this aspect of democracy is that it can help improve the quality and reach of policies, laws, and service delivery. But given risks around government misuse of data and the potential to advance bias through increasingly automated provision and related barriers to public trust, democratic government use of AI requires ongoing monitoring and attention to ensure fairness, equity, and rights-protection.

The fourth intersection relates to AI’s impacts on social cohesion, rights, and socioeconomic conditions. Social and economic inequalities can erode democracies, as grievances can breed polarization and distrust in institutions.34 Given indicators that AI will transform labor markets, with projections from the World Economic Forum predicting some 92 million jobs could be displaced by AI by 2030 (while some 170 million new ones may emerge), considering the knock-on effects for democracy will become critical.35 These impacts on workforces can transform politics in direct ways (changing the shape and size of government workforces) and indirect ways by changing society, the economy, and the political climate. AI offers risks for heightening polarization and extremism, degrading social cohesion, and advancing inequalities, while it also offers promise to help build democratic movements and communities.36 Here, too, AI presents a double-edged sword, offering opportunities to support democratic movements and aspects of socioeconomic progress through labor market opportunities and services to support marginalized groups.37

Outside of these four critical intersections, the wider contextual landscape that shapes these domains is the broader security and geopolitical environment. While beyond the scope of this paper to explore in detail, this global geopolitical backdrop is important to recognize as AI contributes to shaping the fundamental security of democracies and their relative power in the global system.38

Mapping the state of activities at the intersection of AI and democracy reveals several typologies from which interventions emerge. AI has expanded the pool of stakeholders around which traditional “democracy interventions” once formed. A variety of prominent interventions today have originated from technology firms which have sought to apply innovations for public use. Others have emerged from public and civic spaces, or from policy institutions, seeking to identify and co-create technological solutions in partnership with technologists or by bringing technological expertise in-house. Understanding these different approaches, the relevant constellations of stakeholders, and their relative strengths and weaknesses can help democracy proponents map and discern the different pathways through which relevant interventions are developed and deployed.

AI has expanded the pool of stakeholders around which traditional “democracy interventions” once formed.

The following categories show prominent models of interventions in AI and democracy:

Policy-led, technology-enabled: Some interventions are driven by policy actors seeking technology solutions to address democratic challenges. These originate within policy spaces and flourish from strong tech-policy partnerships, but take on different institutional structures. One example is the Engaged California program, which enables California policymakers to collect and analyze citizen preferences in an effort to amplify their voice in governance.39 The program has used Ethelo, a public input and decisionmaking platform, to gather data as well as Claude and other AI tools to help with sensemaking of the data. Policy actors worked in close collaboration with external technologists, alongside contracted program designers with expertise in policy and technology, to collaborate with the state government’s Office of Data and Innovation staff to build the program.

Politics-led, technology-enabled: Another category of interventions stems from politics. Election campaigns are leveraging technologies like ElevenLabs to detect misuse of their voice and other tools to improve their ability to listen to and process diverse information from voters and constituents. Some are using generative AI for political advertising, raising many risks for democracy related to personalizing propaganda and influence while also offering benefits for democracy by enabling constituent-centered, responsive campaigning.40

Civil society–led, technology-enabled: Another model is led by civil society actors, who seek to expand and scale their advocacy and monitoring role by integrating technology tools and expertise into their agendas and activities. Examples include the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research (DFR) Labs and Amnesty International’s Mobile Verification Toolkit, which both employ and partner with technologists to develop tools to identify malign use of AI on elections and other democratic spaces. Another example is Doublethink Lab’s global civil society network, working to deploy computational tools to map Chinese malign propaganda and influence.41

Technology-led, policy-deployed: Increasingly, powerful democracy interventions include those innovated by technology firms that seek to apply them to policy spaces. Those driven by powerful companies in the technology industry include Google DeepMind’s Habermas Machine, an AI-driven dialogue and conflict mediation tool, provides one example of this approach. Google technologists developed a tool for social and democratic purposes, applying it to social policy spaces through partnerships with government actors who seek to better understand citizen preferences.42 The machine was deployed in the UK to identify common ground on divisive policy issues, such as immigration, minimum wage, and childcare policies. In another example, Pol.is and Google Jigsaw’s sensemaking tools were deployed to collect and analyze data from citizens in Bowling Green, Kentucky, in partnership with strategy firm Innovation Engine. They quickly gathered data to highlight areas of mixed public opinion and alignment, revealing public agreement on community priorities around roads and traffic to inform relevant road system policy interventions, among other areas.43

The four archetypes of interventions differ in important ways, each with distinct merits and implications for democratic outcomes.

No one constellation of actors will suffice. Institutions must therefore consider the requisite policy and technology expertise and civil society oversight that shape different interventions, and the potential blind spots that can arise in different models. For example, a technology-led intervention can lack sufficient understanding of policy nuances and unintended social consequences and may lack related monitoring and evaluation. A policy-led intervention can lack sufficient technological expertise, requiring attention to partnerships or hiring within policy organizations to ensure requisite capacities to integrate technological solutions into policy interventions and to sustain them. Because of their scale and access to resources, technology-led and policy-led interventions are particularly important for democracy advocates to examine and identify strategies to ensure their maximal impact in designing interventions and developing partnerships to support them.

Scholars are calling for the training of a new cohort of “public interest technologists,” given the imperative of improving digital skills among public servants to ensure the promise of technology is met for democratic institutions.44 Building on these considerations, it is essential for democracy-relevant efforts to critically assess organizational capacity to balance technological capacity, policy expertise, and civil society engagement and oversight to maximize effectiveness and mitigate risks in any intervention model.

This section highlights issues raised by experts as key challenges at the intersection of AI and democracy. It is followed by a discussion of potential opportunities.

The influence of technological change on elections remains a critical concern for democratic processes, including the potential effects of AI on the voter information environment, design and content of political campaigns, and the administration of elections and electoral institutions.

Public trust in electoral processes and institutions is fundamental to democracy. The 2025 Carnegie California AI Survey reflected high levels of public concern about the effect of AI on the political climate that can shape election cycles, with a majority (55 percent) of respondents saying they are “very concerned” about AI-generated content online heightening political violence and polarization, and a still significant number (27 percent) saying they are “somewhat concerned.”45 Respondents reported mixed optimism about AI’s productive use in democracy, with citizens evenly split on whether AI can help them become “a more informed and engaged voter and citizen” (with an equally significant number reporting “don’t know”). Such findings indicate an ongoing need for governments to better communicate about how AI can help and hinder elections.

AI’s direct influence on elections through its impact on political content is already visible. Domestic and foreign actors aiming to sway election outcomes can use AI to produce synthetic and multimodal content to attack political rivals or to persuade voters through partisan and misleading information.46 Deepfake videos have been detected in efforts to influence elections across the world.47 This includes sexualized deepfakes and other attacks on female politicians, which not only harm candidates directly but can create a chilling effect that discourages women from running for office.48

Combinations of civil society, government, and private sector companies have worked to track influence in elections. Policy-led monitoring interventions include the work of the European Union (EU)’s External Action Service, which reports on foreign influence campaigns targeting EU and neighboring elections.49 Technology companies also deploy various watermarking and provenance efforts aiming to enable users and monitors to determine the authenticity of content. Meta, for example, requires AI content used in elections to be marked with disclaimers. OpenAI has emphasized banning political uses of AI and notes its use of AI to automatically reject hundreds of thousands of requests to generate images of political candidates.50 But researchers find these monitoring and watermarking efforts have limited effectiveness, indicating the imperative for more comprehensive solutions.51 For example, New York Times reporting found limited watermarking of AI-driven content on Meta platforms in a recent Indian election.52 Some companies are engaged in work to identify and combat influence campaigns in addition to implementing standards on disclaimers. OpenAI claims to have disrupted influence operations aimed at voters in elections in the European Union, Ghana, India, Rwanda, and the United States,53 but the scale of the risk and evidence of AI’s influence to shape electoral results demonstrates the need for additional safeguards.

Political campaigns and social movements can also use AI to personalize efforts to influence voters in the content of their campaigns, refining messaging in addition to creating text, images, and voice content. While these capabilities can bring benefits, discussed later, they also raise risks around the proliferation of increasingly sophisticated and personalized propaganda and misinformation campaigns. These concerns arose in the recent election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in India, where “hyper personalized” AI-powered avatars were used to reach citizens, aiding influence campaigns.54 Democracy advocates underscore the importance of deploying multiple tools and approaches to counter these harms, given the limitations of regulation practices alone.

Beyond risks to the information environment, AI’s impact on election administration is another concern. LLMs that share information about voter registration, voter identification requirements, polling access, and more could potentially contribute to voter suppression, either through the spread of misinformation (as documented in a U.S. state election where generative AI robocalls aimed to discourage voters55), by spreading outdated information, or by overwhelming electoral systems.56 These issues can have immediate impacts on voters’ choices and abilities to vote. They can also have wider destabilizing effects if they undermine public trust and election credibility.

How governments use AI raises additional risks for democracy beyond elections. AI is already being used in a variety of government settings, from automating daily workflows to major government programs,57 yet policies and guardrails are fairly limited at the moment.58 The U.S. National Conference of State Legislatures found that 64 percent of federal government employees and 51 percent of state and local government employees reported “using an AI application daily or several times a week,” in fields like border patrol, drone manufacturing, biometric data collection, and more.59 However, in the absence of comprehensive guidance, public sector entities are increasingly seeking additional expertise about regulatory and ethical compliance from private sector firms like Credo AI, Civic.AI, and others, constituting what critics call a form of legal “whack-a-mole.”60

Close monitoring and regulatory guardrails on government use of AI is necessary given the risks of unintended effects or active discrimination. As an example, in 2013, Kenya used AI technologies to support their efforts to collect and analyze fingerprint data to administer voting, but the data failed to but found identify citizens with callused hands, revealing how these technologies can struggle to fairly reach across populations.61 AI-related government interventions must take questions of bias and equity into their design and monitoring to ensure potential interventions do not disenfranchise or harm citizens.

Beyond the potential for unintended consequences, human rights monitors raise serious concerns about intentional harms that can stem from government misuse of AI. Publics have generally been skeptical of technology’s ability to increase government collection of personal data, reflecting cross-cultural norms whereby “historically, people have recognized the value of anonymity in public spaces.”62 Numerous cases have revealed how governments use AI to repress populations, enhancing the scale and sophistication of already worrying clampdowns on civil society worldwide. AI-assisted government repression manifests in different forms, including enhanced surveillance, online censorship, and targeted persecution of online users. It can also facilitate internet shutdowns, government propaganda, and state-led disinformation campaigns.63 These concerns raise stark challenges for policymakers and practitioners who wish to prevent or respond to abuses, especially in autocracies.

As just one concerning example of potential uses of AI for repression, human rights activists have criticized the Chinese government following reports of its use of AI emotion-detection software to support repression of Muslim Uyghers in Xinjiang.64 Similarly, Iran’s use of AI for facial recognition, geolocation, and analysis of web traffic has reportedly been used to surveil and suppress women’s protest movements.65 Democracy proponents are urging governments to impose sanctions on entities that enable or engage in AI-facilitated repression, as illustrated by calls to sanction the Chinese firm Tiandy after its technologies were used for repression in Iran.66 Advocates have also used evidence from monitoring efforts—such as Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net reports—to push technology companies to cease sales of AI products to authoritarian regimes.67

These concerns will require close tracking, especially given data from global democracy indices about closing civic space and rising rates of government repression.

AI also has potential to shape the wider social, economic, and political climate through various pathways that can undermine democracy through immediate and/or longer-term effects. These impacts can manifest through various secondary impacts on the political environment that can undermine democracy, even if they do not directly impact government institutions or elections.

Studies have found that LLMs can produce politically biased and highly persuasive content, which can undermine democracy by influencing political views, though these effects vary depending on topic, model type, and other factors.68 Carnegie’s President Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar and scholar Seth Lazar caution that language model agents, which are AI systems using LLMs, can spread misinformation even more convincingly. They warn that this could drive people away from online spaces, further erode public trust, and reinforce ideological rigidity. As they note, “if you could just as well be talking to a human as to a bot, then what’s the point in that conversation at all.”69 It’s a grave risk that AI’s influence in public squares could wreak havoc on the foundations of trust and participation central to democratic flourishing.

It’s a grave risk that AI’s influence in public squares could wreak havoc on the foundations of trust and participation central to democratic flourishing.

But it is not just the information environment that is at stake. Research indicates economic disruption can play a role in democratic backsliding—in concert with other factors, including culture, legal change, leaders, and media.70 As a result, AI’s broader interactions with jobs and the economy may also impact democracy. But the nature and scale of AI’s potential economic disruption remains disputed. Current analysis suggests that AI’s impacts on job markets have been limited. An October 2025 Brookings study, for example, saw no notable change in the proportion of workers in occupations exposed to AI since ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022.71 Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs estimated in August 2025 that innovation related to AI could displace 6 to 7 percent of the U.S. workforce, finding technology industry employment rates declining and younger workforces disproportionately affected in the face of rising AI adoption.72

Even if these immediate effects have been limited, surveys suggest populations are growing increasingly worried. The Carnegie California AI Survey reported the potential disruption of jobs by AI as a major concern across demographic groups, though most also report that AI will be important to the state’s economic growth and competitiveness. About half of the Californians polled believe that the use of AI in the workplace will lead to fewer job opportunities for themselves in the long run, while only 8 percent believe AI will improve long-term job prospects.73 AI’s effects on the economy through job losses, wealth concentration, or other factors will require continued scrutiny and mapping to guide policy responses.

As challenges increase, so too do potential opportunities for using AI to strengthen democracy. These opportunities, however, are often not well understood and face high levels of mistrust from the public.74 It’s imperative that governments are transparent and communicate about how they are using AI alongside attention to safety and requisite guardrails.

Various AI interventions to improve campaigns and elections have demonstrated the potential to increase their representativeness, with many efforts in early pilot stages. Technology-led interventions have developed so-called broad listening tools that include AI components that can help policymakers and politicians capture vast stores of information, attempting to improve the responsiveness and ultimate success of campaigns to reflect the preferences of the people. These practices, sometimes referred to as demos scraping, offer promise that proponents suggest may help improve policymakers’ and political candidates’ responses to voter preferences.75 AI listening technologies, such as Cortico, use a mix of AI and human sensemaking to better capture recorded audio from small-group dialogue.76 These tools can help candidates better represent electorates, though they also come with risks in relation to the misuse of data and the potential for influence, as explored earlier. Other politics-led interventions are emerging as political candidates leverage AI to interact with and connect with voters, as evidenced in 2022 elections in South Korea, where presidential candidates began to use AI avatars to communicate with voters.77 Similar innovations have grabbed headlines in Japan, a young AI engineer turned gubernatorial candidate who rose to prominence when he deployed an AI avatar to answer voters’ questions, and where work has since expanded under a new party working to use similar technologies to support public questioning and input into Japan’s legislative process.78 Other politics-led innovations include emerging efforts among technology-focused political parties to develop AI-generated policy platforms in Denmark.79 Such uses raise important questions among critics related to human oversight in political decision-making while advocates are hopeful the tools can help candidates better process and disseminate information that reflects the priorities of voters.

AI can also help electoral institutions and election administrators reach voters by improving the accuracy and reach of voter registration, outreach, and election administration. Some election administration interventions are technology-led, developing in partnership with policy and civic actors. For example, Anthropic’s partnership with Democracy Works has aimed to promote the safe and trusted use of generative AI for voter information through the platform.80 Others are led by policy actors, enabled by technology tools and systems to simplify once burdensome administrative processes. Examples include programs developed through the U.S. Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), which has used nongenerative AI to support voter roll management, reaching populations who may be missed by conventional practices and correcting errors.81 Some U.S. states, such as New York and California, are deploying generative and nongenerative AI chatbots to answer basic voter questions about voter eligibility and procedures or to support language translation.82 AI has in fact supported the large scale translation of voter materials in many contexts, meaningfully expanding the reach of voter materials in politically diverse settings, with another example being the translation of voter materials in multilingual India.83 Also in India, the Election Commission has introduced an AI-powered system in a voter-verified paper audit trail, which has led to higher voter confidence, though scaling to machines across constituencies and mitigating technical errors remains a challenge.84

AI may also improve the quality and scale of political polling. Scholars find that high quality and accurate polling can serve as a “pipeline from the governed to the government,” enabling citizens to influence political outcomes.85 Studies show that LLMs can generate polling data closely mirroring human-produced results in certain contexts, with potential to conduct larger-scale and more accurate polling than conventional practices. While current models have limitations, data quality is likely to improve as LLM capabilities advance.86 Scholars working in Mauritius used AI-driven sentiment analysis to analyze existing data to successfully forecast election outcomes, offering a tool for political forecasting that can be especially beneficial in areas with limited polling infrastructure.87

Some civil society groups are using AI to strengthen election monitoring and advocacy efforts, which serve as checks on power to monitor and protect democracy. These civil society–led, technology-enabled efforts include technologies to detect election interference, such as the Atlantic Council’s DFR Lab’s Foreign Interference Attribution Tracker (FIAT).88 Pre/de-bunking campaigns that have been leveraging AI to gather and analyze data to capture mis/disinformation include Google’s pre-bunking campaigns and work by the Sleeping Giants global collective.89 Amnesty International’s Mobile Verification Toolkit (MVT) has been working to support civil society efforts to identify evidence of unlawful surveillance or digital attacks that undermine democracy by targeting campaigns and activists.90 Audio-focused AI companies such as ElevenLabs offer tools to analyze audio content for authenticity that may help politicians track misuse of their voice for malign election influence.91

AI may help dramatically scale and even improve the quality of citizen dialogues through activities to advance deliberative democracy. These efforts to collect and analyze citizen inputs into policy deliberations “can enhance public trust in government and democratic institutions by giving citizens a more meaningful role in public decision making.”92 Preliminary studies found AI tools have driven productive outcomes in deliberation models, decreasing adversarial messaging, amplifying marginalized voices, and improving consensus-building.93 While these benefits offer hope to expand citizen input into the policymaking process, deliberative democracy efforts (including those with AI components and those without) require attention to representativeness in citizen engagement and attention to ensuring these forms of input translate to meaningful policy impact.94

Some efforts have applied AI components to online deliberation platforms, such as Pol.is and Remesh.95 These technology-led programs, which pre-date AI, have begun to leverage AI to support contemporaneous translation, automated moderation, and educational support for participants, as well as facilitate high quality and efficient sensemaking—leveraging AI to analyze large amounts of data to develop actionable insights for policymakers. With potential to improve the speed, scale, and quality of consultations, these efforts may help improve policy responsiveness to citizen demands and combat democratic threats such as gridlock and polarization. Much of this work is in the early stages with limited documentation of the concrete impacts of these tools on democratic metrics beyond the setting of a small-scale experiment, but experts share considerable interest in the potential of these tools to enhance citizen dialogue and democratic participation. Technology companies have developed and piloted different applications of these tools for policy deliberations, including through partnerships with local and national policymakers.

Governments have begun deploying these tools in policy-led interventions at international, national, state, and local levels. For instance, the newly launched Engaged California program, run by the state government’s Office of Data and Innovation using the technology platform Ethelo, aims to help Californians engage with government officials to share concerns and preferences, with pilot programs focused on disaster relief. The program is leveraging AI primarily in the sensemaking process to help government officials analyze citizens’ contributions, developing in partnership with civil society collaborators. California policymakers involved in these efforts have used AI tools such as Claude to help public officials extract meaning from large amounts of qualitative data, a process that was previously incredibly difficult and time-intensive.

Engaged California has been influenced by the extensive deployment of AI tools for deliberation models in Taiwan and elsewhere, building on efforts to expand the concept of “digital public squares.”96 Other policy-led efforts include the French Citizens’ Convention on the End of Life, which used AI to help summarize large amounts of information through the platform Make.org to increase transparency around the deliberations,97 and efforts to develop deliberation tools through the Arantzazulab democracy innovation laboratory in Spain, in partnership with civic groups like DemocracyNext and academics from MIT’s Center for Constructive Communications.98 Policymakers have used these platforms to help citizens engage with policy issues and share their preferences beyond the traditional constraints of physical public gatherings. Experts and practitioners are increasingly focused on expanding these initiatives, including in terms of the numbers of participants, broadening the levels of governance they inform, increasing the numbers of deliberations across settings and issues, and improving the institutionalization and quality of their use.99

Broadening the lens further, technology-focused civil society groups are even trying to increase democratic and collective inputs into AI model development. This work builds on calls to “democratize AI” by defining and evaluating the “democratic level” of AI models and working toward more participatory and public-interest AI.100 Further effort to identify how public input can meaningfully influence model development will be necessary, especially given the potential power and influence of AI models on democratic outcomes.

Existing efforts to increase democratic input into model development include various technology-led initiatives, including Anthropic’s Collective Constitutional AI, OpenAI’s Democratic Inputs to AI grant program, Meta’s Community Forums, and Google DeepMind’s STELA project.101 But critics point to the need for democratic checks on these activities from civil society and others to enable inputs that are not owned by technology firms, in service of “pluralistic, human-centered, participatory, and public-interest AI.”102 In light of such critiques, Nathan Sanders and Bruce Schneier point out the importance of these “alternatives to Big AI” given big technology companies’ market monopolies and “perverse incentives,” and point out the importance of citizens’ investments in public alternatives such as Switzerland’s free public Apertus AI model103 and other work to build public alternatives in Singapore and Indonesia. Nonprofits are also building open-source models as alternatives, attempts expand civil society’s input into AI model development include the LM Arena project, and efforts to balance the Western-centric models and inputs,104 such as the work of Africa’s Masakhane project.105 But challenges remain in enabling these alternative models to sufficiently compete with powerful technology companies and their market advantages.

The influence of AI on government services and government institutions is nascent but potentially transformative. Policymakers and technologists, sometimes working in partnership, have identified numerous ways that AI can improve public services and government work, benefits that could prove impactful in government settings notorious for inefficiency.

Applications of AI to improve government efficacy and efficiency include using AI tools to draft memos and legislative text, to summarize hearings and research documents, to analyze stakeholder positions, and to simplify complex language.106

Civil society initiatives are working to monitor and advise on AI use in public policy, especially given many of the previously discussed risks related to government use of AI. Such efforts include the AI-Enabled Policymaking Project, a collaboration between the RAND Corporation, the Stimson Center, and the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, launched recently as a “new R&D and product lab pioneering ways to integrate AI into the policymaking process.”107

Other civil society–led initiatives are working to use AI to improve development outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. The potential for these efforts to drive development gains is notable especially as they are unfolding at the same time as traditional funding for global development programs is contracting.108 Global “AI for Good” initiatives—backed by firms like Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Apple—have deployed pilot-style interventions driving some positive results in a variety of contexts, showing some promise to support conservation, health systems, disaster prediction, and more.109 This includes programs that have used AI to support global health and agriculture in various global settings, for example, through programs through Jacaranda Health and Digital Green in India, and through innovations in drone-delivered vaccine service in Rwanda and Ghana.110 Yet critics warn of risks to local control and risks of exploitation, underscoring the need to monitor potential harms.111

Governments in Europe and Asia have also grown large policy-led AI programs enabled by technology partnerships and applications that aim to improve citizen-government communication and government program reach. Programs and interventions include popular AI chatbots helping to process citizen inquiries. In Singapore, an AI-powered virtual assistant program called “Ask Jamie” manages citizen queries across more than ninety government agencies to help deliver information and support citizen use of public services,112 and a similar use of AI-enabled chatbots is being deployed in Estonia.113 These uses of AI for public service delivery offer considerable promise to advance government efficiency and reach, though they come with risks related to data breaches as well as potential mistakes and bias, requiring safeguards and monitoring.114

AI may also improve the quality and pace of lawmaking. Tools such as Lexis+ are working to aid in legal research and drafting, with potential to shape the rule of law by enhancing legal implementation and the speed and efficiency of lawmaking. AI can potentially help with tasks such as identifying legal loopholes115 and helping lawmakers write complex regulations,116 though these efforts, too, require continued monitoring and experimentation to reduce the risks of bias and ethical dilemmas. The use of generative AI to write laws remains a question of continued ethical scrutiny requiring urgent attention, especially with reports that AI was “secretly” used by lawmakers to write an ordinance in a Brazilian city—an interesting test case in a country with a complex, overloaded legal system—one that is increasingly turning to AI to automate judicial processes, including tools for legal research, transcription, and caseload management.117

AI’s potential to support social justice and economic growth adds an additional dimension to debates around AI and democracy. While AI poses a host of challenges for socioeconomic conditions and social cohesion, it also brings tools to support democracy advocates and civil society in their work. Interventions in this area are diverse, including many driven by civil society working to use AI to support monitoring of digital abuses and adverse incident reporting.

Some civil society–led, technology-enabled activities are focused on using AI technologies to help detect instances of bias and harm from AI. Examples of these initiatives include the work of Eticas.ai, Humane Intelligence, and TechTonic Justice, whose agendas work to identify bias and misuse in AI systems.118 Other activities driven by civic groups around the world are working to leverage AI technologies to expand public participation and community-building.119

Scholars of democracy movements identify potential for social activists to use LLMs and other AI tools to improve messaging (and “counter” messaging), helping social movements tailor messages to different audiences.120 Social movements can also turn to small language models and distributed computing, which would enable AI applications to run independently of the internet, a lifeline for movements working in restricted internet contexts. As scholar Erica Chenoweth writes, “This strategic use of AI for information management and narrative control could prove crucial in leveling the playing field for democratic actors against more resource-rich adversaries.”121 Because many civic organizations note a need to improve skills and capacity to leverage AI tools in their work, efforts to link democracy movements with tech skills and technologists through initiatives such as the Code for All Network may help strengthen civic organizers’ operational capacity and effectiveness to use AI in their work.122

AI also holds potential promise to support peace and the conditions for postconflict democracy. These interventions include a number of policy-led and civil society–led efforts that are primarily at an early stage, lacking wider uptake and evaluation. Yet growing investments in these areas signal rising interest in AI’s application as a tool for peace. Some efforts to use AI for peacebuilding include work from the Chr. Michaelson Institute (CMI) using LLMs for digital dialogues in Sudan,123 machine learning activities aiming for peace negotiations in Yemen,124 and efforts led by the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs to use AI for peacebuilding in Libya.125 In Libya, project leaders found AI was a useful tool to expand the Libyan populations’ participation in local dialogue to inform political processes.126 In Yemen, a study found machine learning tools helped mediating teams improve their knowledge management, information extraction, and conflict analysis with potential to subsequently strengthen peacebuilding approaches.127 Much of this work is in pilot form, with various logistical difficulties for deploying them in contexts of fragility and instability, not least related to restrictions on internet access and internet freedom. Proponents are focused on further testing and scaling tools to explore potential applications for peace.

Democracy and AI remain catalytic in their interactions—constantly intersecting, influencing, and shaping existing challenges and opportunities, while also creating something new. In an important year ahead for democracy’s future, our mapping finds work at the intersection of AI and democracy is active, but diverse and boutique, indicating the importance of a focus on institutionalization and scaling solutions.

For AI to, on balance, benefit and not weaken democracy, more work is needed to identify the most promising interventions. The four intersection points mapped in this paper present a diversity of spaces where efforts can shape democracy—from elections to wider domains around citizen deliberation, governance, and social harmony—factors that are in turn shaped by the broader environment of peace, geopolitics, and security.

We found that many interventions lack a formal “democracy” label, and many are in early stages. There are some benefits to this terrain, as it signals iteration and experimentation, which may lead to tailored interventions for specific contexts and issues. It raises a challenge, however, because of the diversity of potential routes for automation to influence democracy. A fulsome understanding of the range of activities and interventions potentially relevant to their field requires democracy actors to widen their aperture beyond traditional sectors for a more complete view of how democracy will be molded and shaped in the future.

The strength of democratic institutions, including government and civic organizations, to leverage the benefits and mitigate the drawbacks will be paramount, requiring focus not only on rapidly shifting technological and sociopolitical changes but also on shoring up institutions to maximally address them. Technical solutions must also bring in social and cultural expertise with attention to local context—a challenge laid bare by the fact that evidence suggests that a majority of disinformation campaigns within Africa, for example, are foreign-sponsored, and AI-assisted fact-checking systems are trained primarily on Western datasets, risking inaccuracies and potentially distorting local information environments.128

Those seeking to protect democracy will need to monitor the multiple and emerging spaces and variety of actors, institutions, and expertise from which meaningful interventions can blossom. Our mapping identifies promising and diverse interventions originating from civic, technological, political, and policy spaces. Democracy interventions will require innovations to flourish and grow in all of these spaces.

Technology-led efforts hold particular promise given the financial, technological, and innovative power within industry, but interventions driven by technology firms to support democracy require safeguards around issues of control, transparency, and citizen input and deeper engagement with policy actors to understand real-world application of techno-solutionist agendas.

Policy-led efforts also demonstrate substantial promise but require increased technical capacity and civic input to ensure interventions are effective and avoid abuses. Growing this potential requires attention to the development of public interest technologist pipelines,129 and innovations in skill building and staffing efforts such as trainings, fellowships, and secondments to bridge policy and technology skills, especially in light of the financial barriers to hiring and job retention in policy spaces that come from competition with high-paid technology jobs. Democracy work will require effort to identify the conditions that can drive effective interventions in each sector, alongside efforts to bridge siloes that hold back effective collaborations between policymakers, civic actors, and technologists.

Beyond workforces, broader public education efforts will also play a role in supporting democratic movements and social resilience to economic and political shocks. Across democracies and nondemocracies, calls are growing to expand AI education in schools, often involving work across technology, civil society, and public sectors to match policy prescriptions with requisite training and teaching tools. China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have introduced national mandates to expand AI education in schools, while in Europe, countries such as Estonia have expanded AI education programs. In the United States, federal attention is rising to integrate AI in K–12 curricula, with California as the first state to mandate AI literacy across math, science, and history by 2025. Strengthening public education on AI can help bolster democracy by improving citizens’ understanding of these technologies as they increasingly collide with public life and with democratic institutions.

While the task at hand is steep, the dynamism and variety of potential solution sites present promise. With AI bringing simultaneous opportunities and threats for democracy in a critical year ahead for democracy, the diverse array of activities at the intersection of the two domains—including some that may not use the language of democracy but can substantially impact democracy—demands closer analysis to help government, the private sector, and civil society map this potential and invest in the areas with the highest possible impact for democracy during a critical moment. This will require work to develop shared frameworks and metrics around these intersections across sectors, and continued monitoring, identification, and expansion of interventions that can offer maximal benefit for the protection and expansion of democracy in the months and years to come.

The authors are grateful to the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for its generous support to the Carnegie Endowment, which made this research possible.

The research team would like to thank the expert scholars, practitioners, and policymakers who generously participated in consultations during the research process that informed the analysis. Thanks also to Kelly Born, Frances Brown, Tom Carothers, Micah Weinberg, Scott Kohler, Humphrey Obuobi, Raluca Csernatoni, Steven Feldstein, and Saskia Brechenmacher for their valuable insights and feedback, and to Marissa Jordan, Amy Mellon, Alana Brase, and Jocelyn Soly for design, editing, and production support.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

How significant are statements by senior U.S. officials about supporting democracy abroad in the context of a foreign policy led by a president focused on near-term transactional interests?

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

With the blocking of Starlink terminals and restriction of access to Telegram, Russian troops in Ukraine have suffered a double technological blow. But neither service is irreplaceable.

Maria Kolomychenko

Integrating AI into the workplace will increase job insecurity, fundamentally reshaping labor markets. To anticipate and manage this transition, the EU must build public trust, provide training infrastructures, and establish social protections.

Amanda Coakley

In this moment of geopolitical fluidity, Türkiye and Iraq have been drawn to each other. Economic and security agreements can help solidify the relationship.

Derya Göçer, Meliha Altunışık

While AI offers transformative potential, it can exacerbate health inequities and contribute to negative health outcomes along its opaque, transnational value chain.

Jason Tucker