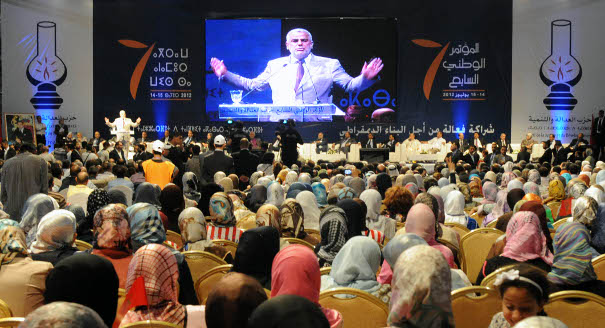

The election of Hamid Chabat at the end of September as secretary-general of Istiqlal, Morocco’s oldest political party, has brought attention to the resurging populist trend that is becoming a distinctive feature of Moroccan politics. Populism has come to dominate political rhetoric, with several figures coming to prominence—most notably, Abdelilah Benkirane, Prime Minister and head of the Party of Justice and Development, and who arguably owes his success to a populist approach. A number of others have also come to dominate the political arena, including figures like Mohammed El Ouafa (also from the Istiqlal Party), Ilyas El Omari and Abdellatif Wahbi from the Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM), as well as Idris Lashkar and Abdelhadi Khairat from the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), among others. Indeed, populism seems to be changing the face of political parties in Morocco as they all pursue this approach to stay relevant.

Populism could not have come back to the fore without the demise of the technocrats, who caved to the 20 February Movement’s demands for radical changes to the political system, which in turn led to the constitutional amendments put to referendum in July 2011. The new constitution reversed technocrats’ former dominance and reintroduced political parties as the main players in the cabinet. With the decline of established politicians, populists themselves have leapt forward and appear to be offering an alternative to their traditional rivals.

Although a definition of “populism” is hard to pin down, in the Moroccan context it has by and large been labeled either as mere invective or as a distinct political style that connects with the average citizen. During the 60’s and 70’s, Morocco saw a similar wave of populist politicians take center stage, with figures like Mohammed Al-Alawi (often referred to as “the Court Jester”); Arsalan Al-Jadidi, the minister of employment, a trade unionist, and a member of the Free National Assembly party’s political bureau; and the famous Said Al-Joumani. According to Moroccan political philosopher Mohammed Sabila, populism’s purpose allows for “the broadening of the parties’ social base”—essentially ensuring that political involvement is no longer limited to the traditional elite, but rather expands in order to absorb broad swathes of society—many of which have rural origins. Political parties began to expand their social bases as a result of the major social transformations Morocco witnessed a shift from a largely rural society to an urban one over the past 60 years. Hence, it became necessary to incorporate the formerly rural population into politics and political parties.

The economic and political changes the country has witnessed in particular require that the ruling elite be replaced by an elite still being formed and trained. The 20 February Movement’s calls for change highlighted the need for a new political class able to absorb popular anger by claiming to be closer to “the people”—speaking to their concerns and addressing them in their language. Parties appear to be succumbing to this tide—even the likes of Istiqlal, which has been dominated historically by the traditional elite. Similarly, the USFP is gearing up to elect its new secretary general, and Idris Lashkar is posed to run in his party’s election (which will be held in a coming weeks). Given the success Benkirane had in drawing attention to the PJD with his approach of simple address, humor, and biting criticism, others seem to be following suit; there is no question that opposition parties will look for competitors capable of challenging Benkirane at his own game, which would indicate that political parties in general may favor populist leaders.

Some observers believe that the presence of populists, at least in the state’s view, encourages greater political participation. As was perhaps witnessed with the increase in voter turnout from 37% in 2007 to 45% in the 2011 elections, according the Ministry of Interior. The state is invested in their rise and is likely to protect them from critics. Others, however, believe that there is an inherent superficiality to populism that not only affects the nature of the political discourse but also prevents the public from reaching a full understanding of what is at stake. Political philosopher Mohammed Boujanal sees populism’s superficiality represented by “Benkirane’s jokes, El Omari’s clamor, and Chabbat’s troublemaking.” There is also a deeper level at which these politicians intersect, and where their one-upmanship and disputes disappear. For this reason, Boujannal asserts that “Populism encourages keeping the Moroccan people at a minimal level [of involvement], represented in enthusiasm and obedience” without having a deeper understanding of the political situation.

Benkirane, El Omari, Chabbat, and others employ this passive populism in order to gain popular approval. The versions of populism may differ but the objective remains the same: political expediency.

Mohamed Jalid is a Moroccan writer, translator, and journalist.

* This article was translated from Arabic.

.jpg)