Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

{

"authors": [

"Dörthe Engelcke"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Sada",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North Africa",

"Morocco"

],

"topics": [

"Civil Society",

"Political Reform"

]

}

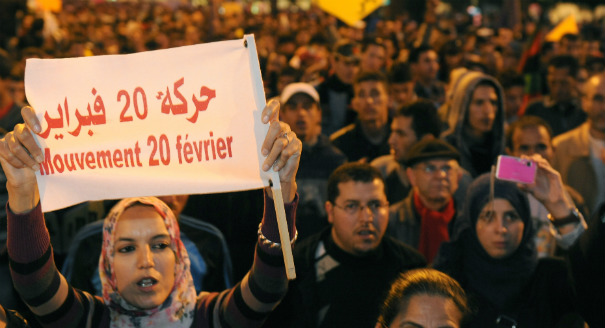

Source: Getty

Moroccan activists formerly associated with the February 20 Movement are redirecting their focus to cultural activities away from overtly political demands.

On December 12, 2015, the Théâtre de l’Opprimé (Theatre of the Oppressed) performed its play B7al B7al (“All Equal”) in the streets of Ain Sebaa, a neighborhood of Casablanca, in front of a crowd of hundreds. The play addresses the issue of racism in Morocco against migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, and the spectators were encouraged to intervene during the play and thereby shape its outcome. The Theatre of the Oppressed was created in Casablanca in 2012 by Hosni Almoukhlis, a former activist of the February 20 Movement. Since then, the group has been organizing performances in the streets of several Moroccan cities, taking on themes of judicial corruption, gender relations, and elections.

The Theatre of the Oppressed is just one of several civil society initiatives that were set up by former activists of the secular, leftist wing of the February 20 Movement after they left it when it began to die down. February 20 was a non-hierarchical, ideologically diverse movement supported by leftist youth as well as Morocco’s largest Islamist movement, al-Adl wal-Ihsan, among others. The absorption of former activists into civil society has meant large-scale protests in Morocco are now less likely.

After 2011, civil society actors began to turn to cultural themes, such as theatre and literature, and put a greater emphasis on operating in the public space. These actors increasingly organize their activities in the streets, having realized through their experience with the February 20 Movement that the political left in Morocco lacks a real power base. The Islamist al-Adl wal-Ihsan, which had formed an important component of February 20, also left the movement toward the end of 2011. The electoral victory of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) that November further underlined the organizational power of political Islam in Morocco and the weakness of the political left. Having found that they lacked enough grassroots support to mobilize, these actors came to view their engagement in civil society as a way of building a popular base instead—that is, working with society rather than against the regime. In contrast to the February 20 Movement, these organizations do not articulate clear demands from the regime but try to trigger change at the grassroots level and educate people about issues they see as central for the creation of a critical citizenry. This approach of individual responsibility leaves the state out of the equation.

Several civil society actors have therefore moved into the public space to reach and engage new audiences and to sensitize new segments of the population. Cultural themes have become one of their preferred vehicles. The Club Conscience Estudiantine, a student organization in Casablanca, began running reading sessions at the school of science at Ain Chock University in Casablanca in 2007. Many of its members participated in the February 20 Movement, and in 2012 the group began to relocate these reading sessions to the public space. So far around 100 of these gatherings of 100–300 participants have taken place in the streets of Casablanca, according to Yassir Bachour, one of the lead organizers.1 The club aims to galvanize students and the general public to make reading an everyday activity.

The absorption of the protest movement into civil society was also driven by institutional factors. Political parties have become unattractive and often inaccessible, leaving civil society the only viable option for some form of political participation. Many former activists had initially joined political parties of the left and the far left, like the Unified Socialist Party (PSU) and the Socialist Democratic Vanguard Party (PADS). However, these parties failed to absorb most of these former activists, who opposed the parties’ hierarchies, archaic internal structures, and lack of internal democracy. Most of the young new members left within a year and began to set up new civil society organizations or join existing ones.2

The state has encouraged this development. Morocco’s new 2011 constitution strengthens the position of civil society. The constitution declares that non-governmental organizations are to participate in the preparation, implementation, and evaluation of state institutions (Article 12). The state is obliged to create institutions, such as consultative bodies, that engage non-state actors in these functions (Article 13), but these bodies have yet to be set up. Citizens also have the right to propose draft bills (Article 14) and present petitions (Article 15). The constitution requires the issuance of laws to regulate these new rights, but though two draft laws concerning the rights to present petitions and propose draft laws to parliament were presented in April 2015, neither has been adopted so far. If properly implemented, the new constitution would give civil society considerable room to expand its political participation, which in turn incentivizes citizens to create and join civil society groups. It also foresees close cooperation between state institutions and civil society, which facilitates greater state control of these non-state actors. In the long run, these concessions toward civil society make it likely that many civil society actors will no longer question the existing political power configuration, but instead try to benefit from the political opportunities that the state opens up.

The regime has tolerated the activities of new civil society actors like the Theatre of the Oppressed and other organizations set up by former February 20 activists—such as the Democratic Anfass Movement and the Prometheus Institute for Democracy and Human Rights—but this should not be interpreted as a decline in state repression. State repression against human rights organizations and activists has increased since 2013. Typically, this targets actors who criticize the monarchy or address sensitive issues like the status of Western Sahara, discussion of which is seen as a threat to Morocco’s territorial integrity. Over 60 events planned by the independent Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH) were forbidden in 2014. Maâti Monjib, the president of Freedom Now, an organization that promotes freedom of speech, faced a travel ban that was only lifted after he staged a hunger strike.

The regime’s tolerance indicates it views these actors as less threatening and approves in particular of the increasing focus on culture at the expense of overtly political demands. In general, these actors have not yet crossed any red lines. For instance, in 2015, a year of local elections in Morocco, the Theatre of the Oppressed was able to perform a play on the topic of elections in several cities all over Morocco without any disruptions from the state. Voter turnout is low in Morocco, undermining the state’s narrative of participatory democracy, and from the state’s perspective, a play that makes people debate elections is therefore likely to be welcomed.

Overall, these organizations focus on gradual change and in that sense—willingly or not—play into the monarchy’s narrative of gradual reform. The absorption of former activists into civil society, the fragmentation of civil society into specialized, ostensibly apolitical actors, and the changing rationale of these organizations have therefore limited the likelihood and prospects of large-scale protest in Morocco. Even though their type of activism has diminished the chances of mass protests in the near future, in the long term it may contribute to changing attitudes at the grassroots level.

Dörthe Engelcke is a fellow at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg, the Göttingen Institute for Advanced Study, University of Göttingen, Germany.

1. Interview with Yassir Bachour, September 7, 2015.

2. Interviews with Moroccan activists conducted between July and October 2015.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

Hate speech has spread across Sudan and become a key factor in worsening the war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. The article provides expert analysis and historical background to show how hateful rhetoric has fueled violence, justified atrocities, and weakened national unity, while also suggesting ways to counter it through justice, education, and promoting a culture of peace.

Samar Sulaiman

Kuwait’s government has repeatedly launched ambitious reforms under Kuwait Vision 2035, yet bureaucratic inefficiency, siloed institutions, and weak feedback mechanisms continue to stall progress. Adopting government analytics—real-time monitoring and evidence-based decision-making—can transform reform from repetitive announcements into measurable outcomes.

Dalal A. Marafie

The chaos of street naming in Sana’a reflects the deep weakness of the Yemeni state and its failure to establish a unified urban identity, leaving residents to rely on informal, oral naming systems rooted in collective memory. This urban disorder is not merely a logistical problem but a symbolic struggle between state authority and local community identity.

Sarah Al-Kbat

While Morocco’s shift to a digitized social targeting system improves efficiency and coordination in social programs, it also poses risks of exclusion and reinforces austerity policies. The new system uses algorithms based on socioeconomic data to determine eligibility for benefits like cash transfers and health insurance. However, due to technical flaws, digital inequality, and rigid criteria, many vulnerable families are unfairly excluded.

Abderrafie Zaanoun