Last February, during Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi’s visit to Qatar, the two countries agreed to connect electricity grids. Currently, Iran’s electricity network is connected to Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Qatar has one of the highest electricity consumptions in the world, (15.316 kWh per person per year) while Iran’s electricity generation and distribution network maintains a capacity of only around 90,000 MW.

The network connection expands the electricity dispatching management center expand, which allows the network’s operation to increase. As a result, Iran and Qatar would be able to exchange energy with each other according to their respective consumption needs and seasonal peaks. The connection of Iran and Qatar’s power grids is a step towards strengthening energy diplomacy, but without a change in Iran’s foreign policy — that is, without the removal of sanctions and attracting foreign investment — it cannot use its full potential in the energy sector and, ultimately, will not be able to increase its influence on the international stage.

Is Iran a Regional Electricity Hub?

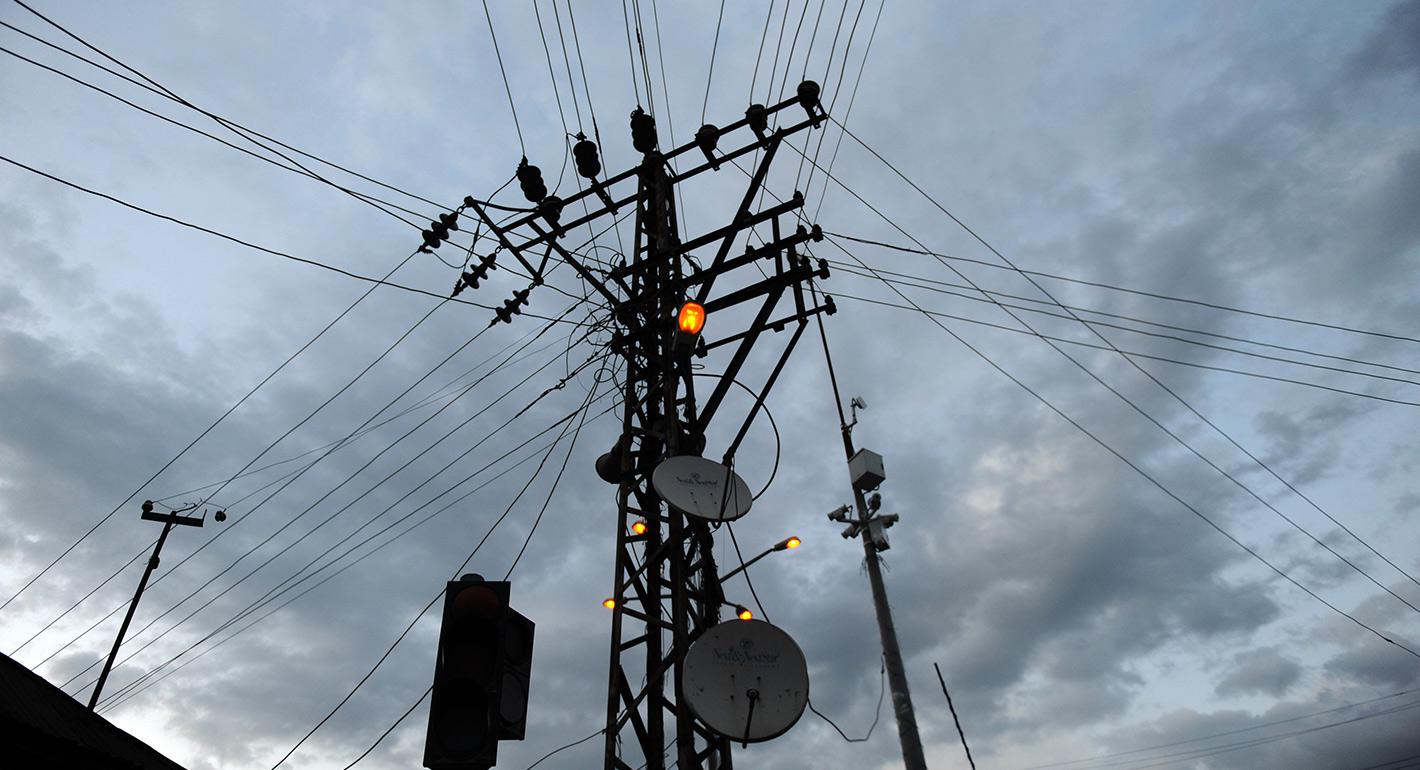

Increasing both energy exports and national power generation has been one of the main goals of in Iran’s Five-Year Development Plan (2016-2021). According to the plan, the government was supposed to make Iran an electricity hub in the region by the end of last year through establishing electricity connections with neighboring countries. Energy experts in Iran believe, however, that without proper investment to develop the infrastructure to supply electricity to neighboring countries, this will not be easy to achieve. While the government says it wants to utilize its electricity sector, it is not investing in it enough to make it an attractive supplier. Power grids are neglected and power plants often lack fuel.

Homayoun Brahmandpour, Head of the Center for Development of High Capacity Power Transmission Technology, asked, "Why didn’t we have a long-term strategy and roadmap for the stakeholders in the regional electricity sector [so that we can] become the regional electricity hub?" Similarly, Payam Bagheri, stressed the importance of turning Iran into a regional electricity hub, where Iran would meet both domestic needs and the needs of other countries in the region.

Applying Iran’s energy diplomacy inclinations to the field of electricity is not appropriate, and certainly not resourceful. There are several other countries in the region who have already connected their electricity systems. Egypt and Saudi Arabia are connected; as well as Jordan and Iraq. Siemens signed an agreement with Afghanistan to turn the country into a central Asian electricity hub. Finally, the UAE invests heavily in and exports nuclear power. Given Iran’s inability to sell crude oil under current circumstances, electricity exports could strengthen Iran’s currency.

Weak energy diplomacy in Iran’s foreign policy apparatus has prevented Iran from playing an important role in supplying electricity to neighboring countries, including Qatar, despite its great potential. The Raisi administration must increase the role of renewable energy in the country’s energy mix and provide the conditions for attracting the capital and technology needed in the electricity sector. Ultimately, if Iran increases its electricity transmission with other countries in the Middle East, it will both increase economic cooperation and strengthen regional security.

Umud Shokri, PhD is a senior foreign policy advisor, energy strategist, and an advisor at Gulf State Analytics (GSA). He is also the author of US Energy Diplomacy in the Caspian Sea Basin: Changing Trends Since 2001. Previously, he served as a visiting research scholar at the Center for Energy Science and Policy (CESP) at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

.jpg)