Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

{

"authors": [

"Katie Tobin"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"American Statecraft and the Global South"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"American Statecraft"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States",

"South America",

"Central America and the Caribbean"

],

"topics": [

"Migration",

"Security"

]

}

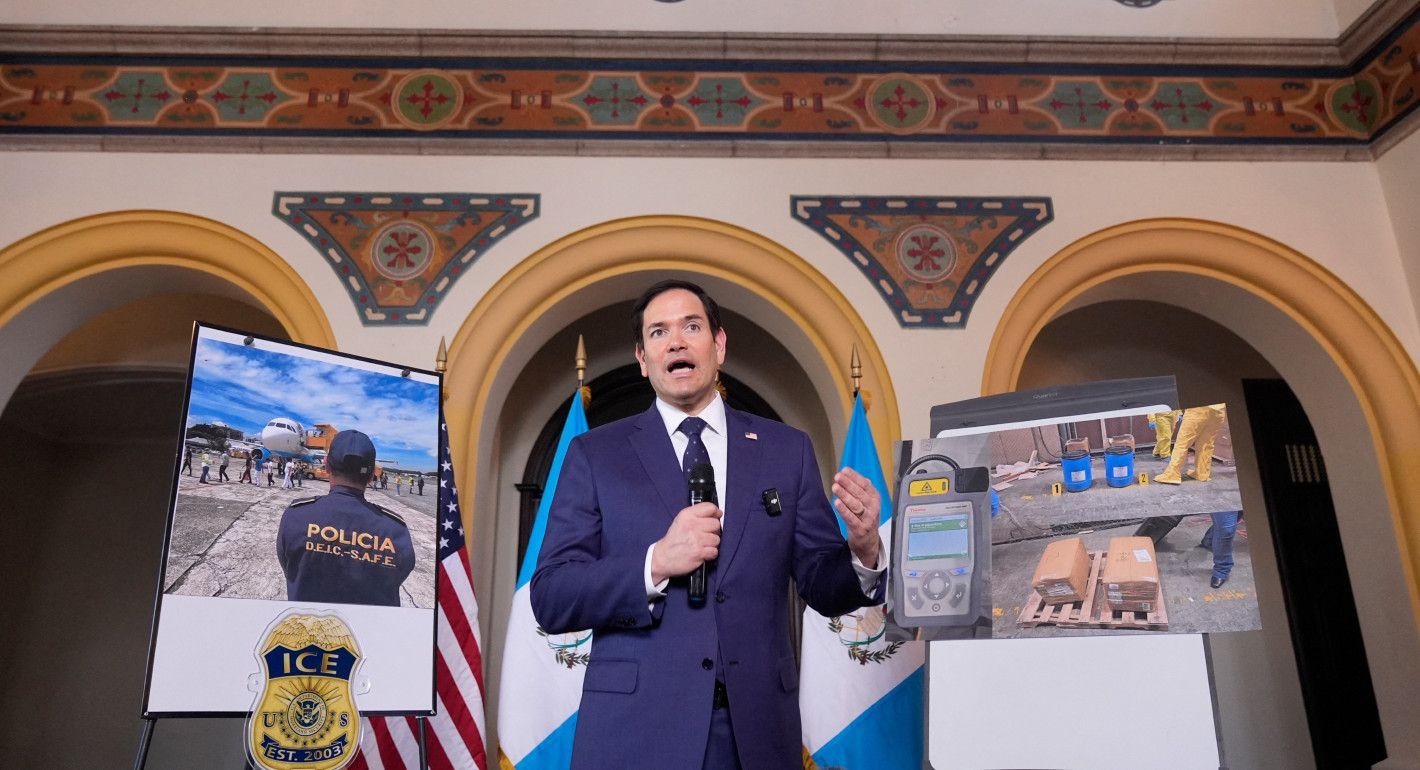

Marco Rubio speaks in Guatemala City on February 5, 2025. (Pool photo by Mark Schiefelbein/AFP via Getty Images)

The secretary of state shouldn’t waste his clout only pushing deals on deportation flights.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s visit to Latin America last week yielded several quick wins for the United States on border security. Both El Salvador and Guatemala agreed to accept more deportation flights of their own citizens, as well as other nationalities. This is not a big surprise: Both countries, as well as Honduras, entered into similar agreements with the first administration of President Donald Trump in 2019. With the exception of Venezuela and Cuba, the United States generally enjoys strong deportation cooperation with countries across the Western Hemisphere.

This begs the question: Are deportation flights the most impactful border security commitment that the new secretary of state can secure from the U.S.’s neighbors? Rubio starts the job with both a deep understanding of immigration issues and tremendous credibility in the region. Leveraging this clout simply to secure deportation deals is a missed opportunity.

Having worked on these issues for decades—both at the United Nations and as a senior U.S. diplomat—I’m convinced that the best way our Latin American partners can reduce northbound migration is by taking steps to stabilize people where they are. This means giving migrants from neighboring countries access to legal status, work permits, and basic social services.

These measures are rarely politically popular with our partners. They require national leaders to allocate dollars to supporting foreign nationals, increasingly against the backdrop of economic strain and anti-immigrant sentiment in their countries. Yet a wave of Latin American countries have stepped up in recent years to integrate migrants and stabilize flows. Since June 2022, Belize, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru each ushered in new large-scale policies to offer migrants access to legal status and jobs—essentially giving compelling reasons for millions more migrants to stay put rather than head toward the U.S. border.

Integration is a central pillar of the Los Angeles Declaration, a regional migration pact that twenty-two countries signed onto two and a half years ago. The framework promotes responsibility-sharing on migration, with each signatory committing to do more to integrate migrants in their countries, expand lawful pathways for immigration, and enforce their borders. At the most recent LA Declaration ministerial meeting in September 2024, signatory countries made a fresh round of commitments related to integration. The fact sheet released after the meeting asserted that these combined efforts have enabled 4.4 million Venezuelans to attain legal status to date.

Regionwide progress on integration, coupled with expanded lawful pathways and increased enforcement across the migratory corridor, has led to a major drop in irregular migration across the Western Hemisphere. Since the height of the migration surge in December 2023, crossings through both the Darien Gap and U.S.-Mexico border have dropped by 80 percent.

Although these recent actions are commendable, they still fall short of the need. Today, at least 2.3 million Venezuelans and scores of other displaced populations remain undocumented and unable to access formal employment across Latin America and the Caribbean. These are the people who are most likely to migrate onward to the United States.

Consider Colombia—the top host country for displaced Venezuelans. Former president Iván Duque Márquez made a bold move in 2021 when he gave legal status to 1.8 million Venezuelans living in Colombia. Duque’s decision had a major stabilizing impact at the time and set an example for other countries in the region. Yet current President Gustavo Petro has been reluctant to extend this initiative since coming into office in 2023. Last year, he announced a plan that could benefit an estimated 600,000 undocumented parents and legal guardians of children with valid Colombian Temporary Protective Status, but it does not benefit the 1 million to 2 million Venezuelans who have entered the country since 2021. Today, most Venezuelans entering Colombia cannot legally stay or work, creating a clear incentive to move onward.

Similarly, Peru, which hosts the second-largest displaced Venezuelan population in the world, has also been reluctant to further expand legal status to the 1.6 million Venezuelans living within its borders. In 2023, the Peruvian government introduced a temporary stay program for Venezuelans with irregular migratory status, granting them the right to work. More than 120,000 Venezuelans benefited from this program, which also facilitates access to health care, education, bank accounts, and other public services. But instead of expanding these efforts, President Dina Boluarte introduced a series of more restrictive immigration measures in the last year, including passport requirements and expulsions.

Recent studies make the case that integrating migrants is actually good for Colombia’s and Peru’s economies. However, ongoing economic strain and growing anti-immigrant sentiment in both countries and across the region is making any expansion of integration programs politically challenging. It will take strategic diplomacy, coupled with continued economic incentives, to encourage reluctant leaders such as Petro and Boluarte to take the bold new actions needed to truly stabilize migration flows.

Despite the political headwinds in Latin America at the moment, Rubio is well-placed to secure these big commitments from the top host countries. In his recent his Wall Street Journalop-ed, Rubio notes that U.S. foreign policy and assistance has historically prioritized other parts of the world over the Western Hemisphere. “As a result, we’ve let problems fester, missed opportunities and neglected partners,” he said, while pledging change. He also noted that “closer relationships with the U.S. lead to more jobs and higher growth in these countries,” which “reduces incentives for emigration.” Rubio should take his own advice and dedicate the diplomatic capital and U.S. resources needed to secure the big integration commitments from our partners to truly stabilize the flow, rather than simply chasing quick political wins.

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

And how they can respond.

Sophia Besch, Steve Feldstein, Stewart Patrick, …