Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

{

"authors": [

"Sophia Besch"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Trump’s Disruptive 100 Days",

"Transatlantic Cooperation",

"European Politics"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Germany",

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Defense",

"Economy",

"Global Governance",

"NATO"

]

}

(Photos by Getty Images)

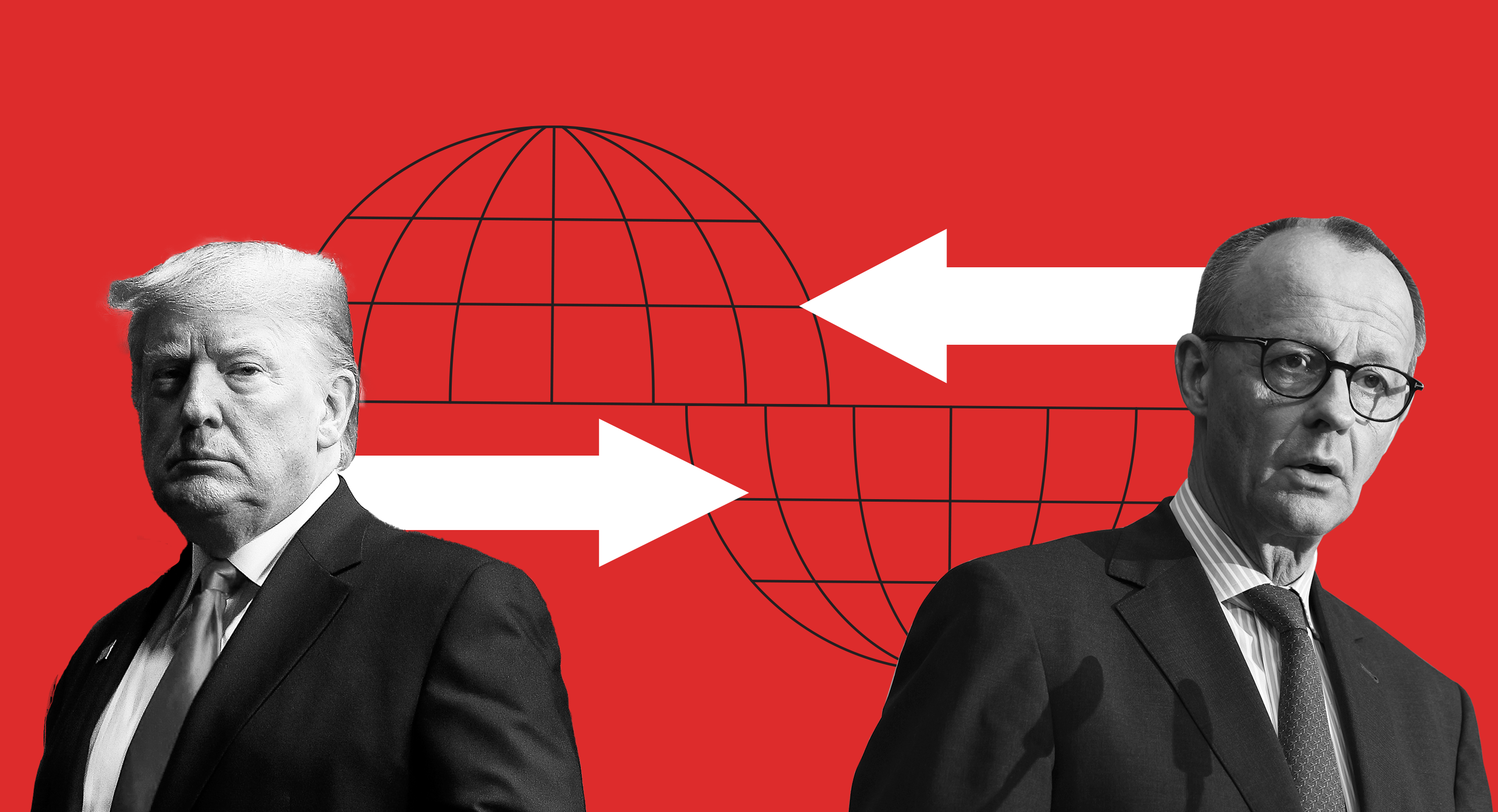

With its second Zeitenwende, Berlin could become a global counterweight to Washington.

This piece is part of a Carnegie series examining the impacts of Trump’s first 100 days in office.

For Germans, the first 100 days of President Donald Trump’s administration have felt like a brutal, multipronged assault on all three pillars of the bilateral relationship with the United States: trade, security, and shared values.

Germany is acutely vulnerable to the threat of U.S. tariffs, with exports to the United States accounting for approximately 4 percent of its GDP. Its security and defense policy is structured primarily around NATO and oriented toward sustaining a continued U.S. presence in Europe—Germany hosts the largest contingent of U.S. forces on the continent and stations American nuclear weapons on its territory. Trump’s initial months in office have cast doubt on the future of these arrangements. These developments are deeply destabilizing, though not entirely unexpected, for German policymakers still marked by the trauma of his first presidency. The White House’s antagonizing of Ukraine, Trump’s readiness to engage in negotiations with Russia without consulting his European or Ukrainian counterparts, and the president’s expansionist aspirations toward Greenland all have heightened concerns that the United States is not merely apathetic but increasingly antagonistic to European security interests.

It was the February 2025 speech by U.S. Vice President JD Vance at the Munich Security Conference, however, that marked a watershed moment in German strategic thinking. For Berlin, Vance’s speech crystallized concerns over the ideological ambitions of key actors in Washington, challenging the foundational assumptions of transatlantic alignment. Vance accused European governments of suppressing free speech and claimed internal issues such as EU immigration and alleged censorship policies posed greater threats to democracy than external adversaries such as Russia or China. The defense of the European political project, the commitment to the EU as not just a market, but a peace and democracy project, is central to the identity of many in the German political elite. And when Vance openly criticized the exclusion of populist parties—specifically naming Germany’s far-right AfD—and subsequently privately met AfD leader Alice Weidel, this was broadly perceived in Berlin as a breach of sovereignty and interference in German domestic politics.

Incoming chancellor Friedrich Merz described the Munich conference as a “historic date” and responded by articulating a new strategic doctrine: step-by-step European independence from the United States—a significant concession from a lifelong staunch transatlanticist.

Most significantly, Merz initiated a historic shift in fiscal policy by exempting defense spending above 1 percent of GDP from Germany’s constitutional debt brake. This legal change could unlock substantial new funding, enabling defense expenditures of 3 percent or even 4 percent of GDP if required. Paired with a $547 billion infrastructure fund to fix Germany’s deteriorating roads, railways, energy, digital, and education systems, the package amounts to a generational investment—framed in domestic debate not only as an economic stimulus, but as a bid for geopolitical resilience faced with an unpredictable U.S. government.

These announcements can be read as a second German Zeitenwende—a paradigm-shifting response to a changing world. Outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz launched the first Zeitenwende in 2022, in response to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the German realization that war had returned to the continent. Merz is responding to the dawning realization that Germans might have to face this new reality without the United States.

Nevertheless, Berlin is adopting a measured tone in its official documents. The new government’s coalition treaty reiterates Germany’s commitment to the bilateral relationship with the United States and avoids any language suggesting strategic decoupling. Policymakers are wary of accelerating estrangement and continue to pursue a de-escalatory line on trade and security.

Merz is seeking to lower tariffs in the short term and envisions a U.S.–EU free trade agreement over the medium term. He has called for nuclear consultations with France and the United Kingdom to “complement” U.S. extended nuclear deterrence, while Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has begun exploratory NATO negotiations to coordinate with Washington a gradual U.S. force drawdown from the European continent. Should the U.S. course shift, Germany would welcome re-engagement. But there will be no going back to the trusting dependency of the past.

America’s changing orientation toward world politics also poses a profound challenge to Germany’s own thinking about its place in the international order.

As a result of the fiscal announcements of the second Zeitenwende, Germany could one day be not only the third-largest global economy, but also a top-three defense spender. It is structurally positioned to play a major global role: With its commitment to free trade and international norms and its reputation for rule-loving bureaucratic and multilateral governance, it might be a welcome global counterweight to the Trump government.

Yet Berlin is fundamentally cautious. Even in the European context, where U.S. withdrawal is leaving behind a vacuum, the German political class and public have so far shown little appetite for assuming a leadership mantle. They perceive themselves as domestically heavily constrained. Germany’s economy has remained stagnant for the past three years, weighed down by elevated energy costs and intensifying competition from China. It remains acutely vulnerable to U.S. tariffs as well as the broader U.S.–China trade conflict, which could result in a surge of Chinese exports flooding the European market. The rise and increasing pressure of the German far right further inhibits assertive foreign policy.

Despite its ambitious defense spending plans, Germany often still defers to the UK and France to step into more forward-leaning security roles. Germany continues to embody former U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger’s quip that the country was “too big for Europe, too small for the world”—a status-quo power navigating a post-American order with institutionalism, economic weight, and strategic restraint.

Its governing paradigm remains one of Anlehnungsmacht—a “power to lean on”: indispensable due to size and economic weight, but reluctant to act unilaterally. But after three years of inward-looking and domestically preoccupied governance under Scholz, Berlin now seeks to reinvigorate and deepen its European and global partnerships. Germany’s preference remains to seek resilience through alignment and shape outcomes multilaterally, particularly through the EU, NATO, and minilateral formats such as the E3 (France, the UK, and Germany), the Weimar Triangle (France, Poland, and Germany), and newer or newly relevant strategic partnerships with countries such as Canada, India, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea.

Germany is deeply worried by the United States’s attack on the international order that has helped Germans thrive after the end of the Second World War, but it has not yet given up on defending that order—it sees no viable alternatives.

Read more from this series:

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

When democracies and autocracies are seen as interchangeable targets, the language of democracy becomes hollow, and the incentives for democratic governance erode.

Sarah Yerkes, Amr Hamzawy

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

And how they can respond.

Sophia Besch, Steve Feldstein, Stewart Patrick, …

They cannot return to the comforts of asymmetric reliance, dressed up as partnership.

Sophia Besch