The Disaster Dollar Database is a tool that tracks the major sources of federal funding for disaster recovery in the United States.

{

"authors": [

"Sarah Labowitz",

"Leonardo Martinez-Diaz"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Climate Disasters and Adaptation",

"Climate Mobility"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "SCP",

"programs": [

"Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Security",

"Climate Change"

]

}

Workers remove hazardous waste from properties destroyed in the Palisades Fire in Malibu, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

FEMA Needs to Change. A New Bill in Congress Shows Promise.

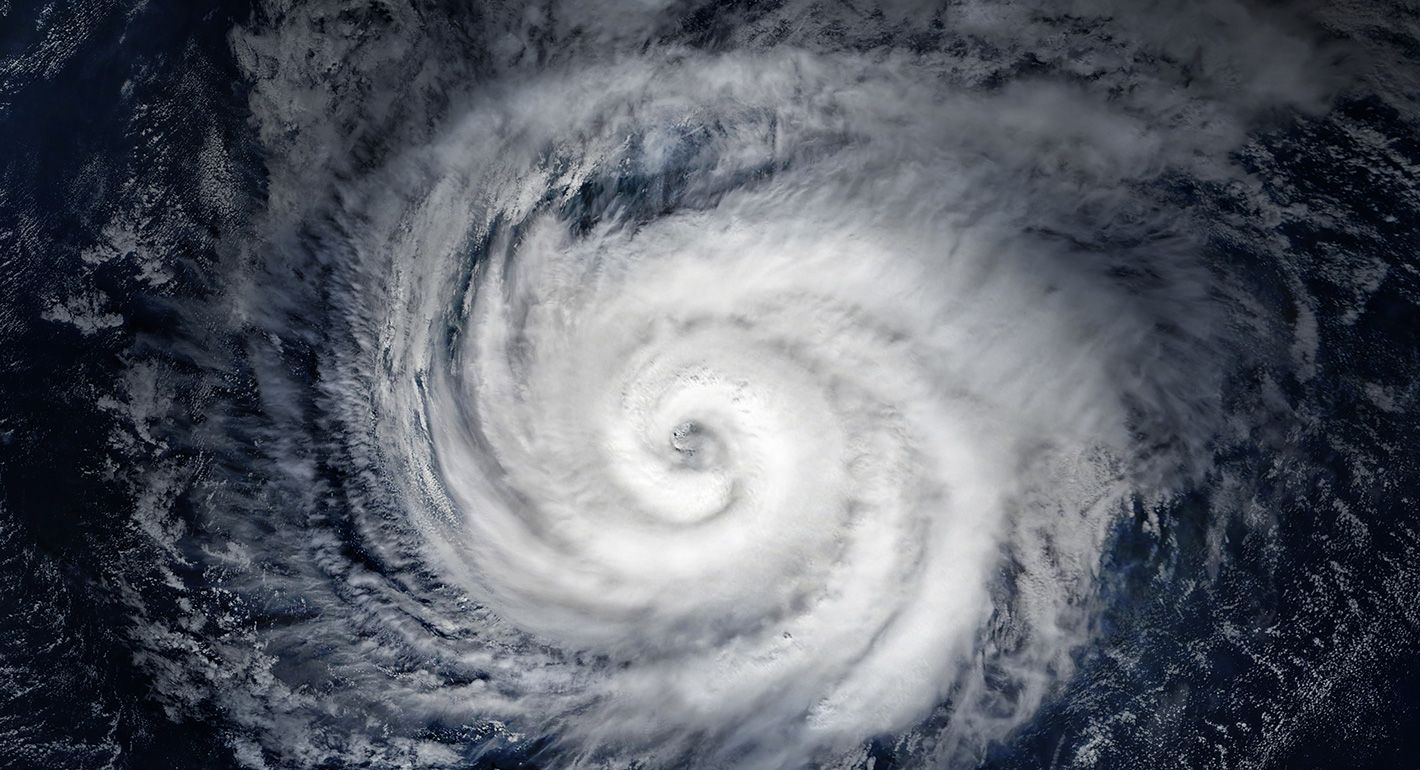

With hurricane season rapidly approaching, Congress and the administration need to work together to overhaul the U.S. disaster aid recovery system—not gut it.

Over the past four months, the administration of President Donald Trump has vacillated on what to do with the U.S. federal disaster aid system. Early on, Trump expressed interest in “getting rid” of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), pushing disaster-related costs to states and households. Then the administration shifted to a vision that would end FEMA “as it exists today” while implementing major reforms. Talk then returned to eliminating FEMA, only to settle again on some kind of reform. Meanwhile, the president created a FEMA Review Council, which is now making plans to meet.

Despite its uncertainty about how to proceed, the administration is right that FEMA and the federal disaster aid system more generally need to change. This is not new. The system is too slow and burdensome for state and local governments and households. It overindulges in micromanagement at the expense of speed and flexibility. It doesn’t do enough to incentivize investments in resilience and risk mitigation. But there are many worthy aspects that shouldn’t be thrown out with the bathwater. The right way to approach reform is in consultation with local leaders, with plenty of runway to implement major changes, drawing on lessons of what’s worked well and could work even better with reform.

Congress is now entering the fray with constructive ideas, and in good time: Hurricane season starts in twenty-six days. A bipartisan group of legislators has introduced a draft bill in the House of Representatives that has three key changes that would strengthen the disaster aid system and improve its responsiveness to Americans.

First, the bill puts in place strong incentives for investing in resilience and risk mitigation. States—even the richest and most familiar with disasters—are woefully unprepared to build resilience and respond to disasters on their own, and red states and congressional districts would suffer most from a federal pullback of disaster aid. (However, despite ongoing misinformation, our analysis of FEMA data also found no meaningful difference in the amounts of FEMA aid that households received in congressional districts represented by Republicans or Democrats.) And investment in resilience is cost-effective because it reduces losses in the first place. Without risk mitigation measures, homes and businesses become too risky to insure, and private insurers drop policies or make them unaffordable, leaving the federal government—the insurer of last resort—holding an ever-larger and riskier bill.

The proposed legislation would create a sliding scale for how much FEMA funds a given disaster recovery project. If a state makes approved investments in mitigation in advance of a disaster, FEMA could cover up to 85 percent of a project’s cost after the storm. On the flip side, if states don’t make those investments, the FEMA portion goes down to 65 percent. The administration is right that states need to step up to invest in their own resilience and insurability. The bill recognizes that the federal government also has an important role to play in supporting and rewarding states that follow through.

A recently canceled resilience program would offer a blueprint. The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program was created during Trump’s first term, and it’s proven hugely popular—so much so that it was oversubscribed before it was canceled. Jurisdictions across the country were eager to have funding to invest in their own resilience before they’re inevitably hit by a wind, water, or fire event.

The bill notes that these projects should be funded without going so far as to require BRIC’s reinstatement. But BRIC has clear bipartisan support. House Appropriations Chairman Tom Cole, a Republican from Oklahoma, endorsed BRIC at a May 5 hearing, describing the program as “extraordinarily helpful.”

But for those on the fence, it might be useful to think about this program as building insurable communities. We’re moving in a dangerous and unaffordable direction on insuring disaster risk. The public sector is taking on the most expensive kinds of risk, without appropriate partnership from the private sector. The federal government should be supporting local governments in increasing communities’ resilience so that they can be insured on the private market at reasonable cost. Maybe BRIC gets a rebrand as Building and Supporting Insurable Communities (BASIC).

Second, the bill flips around the model of how FEMA works for state and local governments in the aftermath of disaster, which will make the process faster, cheaper, and less burdensome for states. Currently, FEMA backstops local recovery by reimbursing jurisdictions for 75 percent of the cost of rebuilding public buildings. But this approach requires jurisdictions to either have the money up front or to take out loans or bonds to pay for rebuilding before FEMA reimburses them. Some states, such as heavily disaster-affected Louisiana, require that local governments do not expend more funds than they have available.

The bill proposes a shift to a cost estimation method, where jurisdictions would get a licensed professional to estimate the cost of repair, which FEMA would use to issue an upfront payment to local government. This has huge potential benefits to local communities by reducing the cost of capital and speeding up how quickly they can start rebuilding.

Finally, the bill would improve the survivor experience in meaningful ways. For example, it would allow homeowners to make permanent repairs to homes with FEMA funding, not just temporary fixes. If your roof was damaged in a storm, FEMA currently can only cover the costs of a temporary repair, such as installing a tarp. This has left many survivors waiting sometimes years for additional programs to help with the cost of replacing their roofs. It’s more efficient to pay for the roof soon after a disaster to prevent long-term damage and make the home livable quickly.

Managing disasters effectively is vital to protecting lives and livelihoods in the United States. The U.S. federal disaster aid system, including FEMA, needs to change to deliver on a national security imperative and meet a moment when disasters are becoming ever more frequent and intense. So far, the Trump administration has identified that some aspects of the system are not working, without offering a vision for improvement. As hurricane season approaches, Congress and the administration should work together to realize the promise of a newly invigorated FEMA and a more secure and resilient United States.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Emissary

- With the RAISE Act, New York Aligns With California on Frontier AI LawsCommentary

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

- The Trump-Modi Trade Deal Won’t Magically Restore U.S.-India TrustCommentary

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- Federal Accountability and the Power of the States in a Changing AmericaCommentary

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

- Trump Wants “Peace Through Construction.” There’s One Place It Could Actually Work.Commentary

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan