The federal disaster recovery system has been one of the many targets for cuts by President Donald Trump’s administration. Multiple agencies that distribute the nation’s federal recovery funds and otherwise equip emergency managers and first responders are in the administration’s crosshairs—most notably, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). So far, administration officials have promised to “get rid of FEMA the way it exists today,” fired four senior FEMA leaders, and reduced staffing by 84 percent at the office that oversees long-term recovery funding for housing and community development. It has also slashed funding for wildland firefighters and announced major changes in staffing at the agency that oversees the weather forecasting that emergency responders rely on.

Taken together, these changes will wholly reshape how the country responds to disasters. State and local governments will have to bear enormous costs if the federal government steps back from its forty-year role in disaster recovery.

That burden won’t be equally distributed: Data from Carnegie’s Disaster Dollar Database over the past decade indicates that states across the Gulf South and mid-Atlantic will be hardest hit. We ranked states by the average number of households seeking FEMA assistance each year, to illustrate what states would need to plan for on an annual basis in responding to their constituents.

In Florida, more than half a million people apply for assistance every year on average. If FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program (IHP) were to disappear, the state would have to create the capacity to respond to those residents itself—plus many more during large storms, such as the more than 2.6 million Floridians who applied for relief after 2017’s Hurricane Irma. Currently, FEMA maintains an online portal, dozens of call centers, and a nationwide workforce that deploys to disaster zones to assist residents in applying for help. Over the past decade, this program has provided an average of $3,398 to more than 1.7 million eligible households in Florida after disasters.

Even more significant is the funding provided directly to state and local governments through FEMA’s Public Assistance program and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program. These programs either reimburse or provide direct grants to jurisdictions for cleaning up debris, paying first responders, rebuilding schools and community centers, repairing roads and infrastructure, and restoring affordable housing.

For states such as Louisiana, these funds are a lifeline in the face of repeated disasters. On average, Louisiana receives about $1.4 billion a year from the federal government for disaster recovery from these three programs alone. (Additional disaster programs from the Small Business Administration, Department of Agriculture, and Department of Transportation are not included in these calculations.) That amount is roughly what the state spends on its entire higher education system. The $2.1 billion Florida receives annually in federal disaster grants approximately equals what the state has already committed to spend to prop up its struggling insurance sector. And Texas’s $1.4 billion in annual federal disaster grant funding is equal to what it currently spends on school safety.

If the federal government removes these programs, state legislatures and local governments will have to retool budgets to make up the difference, try to bring future costs down with spending and regulation to promote resilience, or simply go without. If they don’t, communities—especially in rural places—will struggle to rebuild, accelerating urbanization and migration out of disaster-prone states.

Congressional districts in Texas, Florida, and Louisiana also had the highest number of households that applied for FEMA assistance when looking at the data since 2021, when maps were last redrawn. This reflects the impact of Hurricanes Milton, Helene, and Beryl, as well as less visible incidents such a severe winter storm and major flooding in Louisiana in 2023.

More than twenty-five of the most disaster-impacted congressional districts—as measured by the number of FEMA applications—had more than 100,000 households apply for assistance in the past four years. The average size of a congressional district is 761,000 individuals, meaning that a large percentage of the constituents in these districts have applied for disaster assistance in the past few years.

Of those top twenty-five districts, eight were represented by a Democrat and seventeen had a Republican congressmember. Across all disasters since 2021 where FEMA activated IHP, more people living in Republican districts applied for assistance than those in Democratic ones, but the award amounts were almost identical, regardless of representation. This reflects a tradition of nonpartisan disaster assistance and a federalized system for recovery that spreads resources and capacity across the United States’ expansive geography.

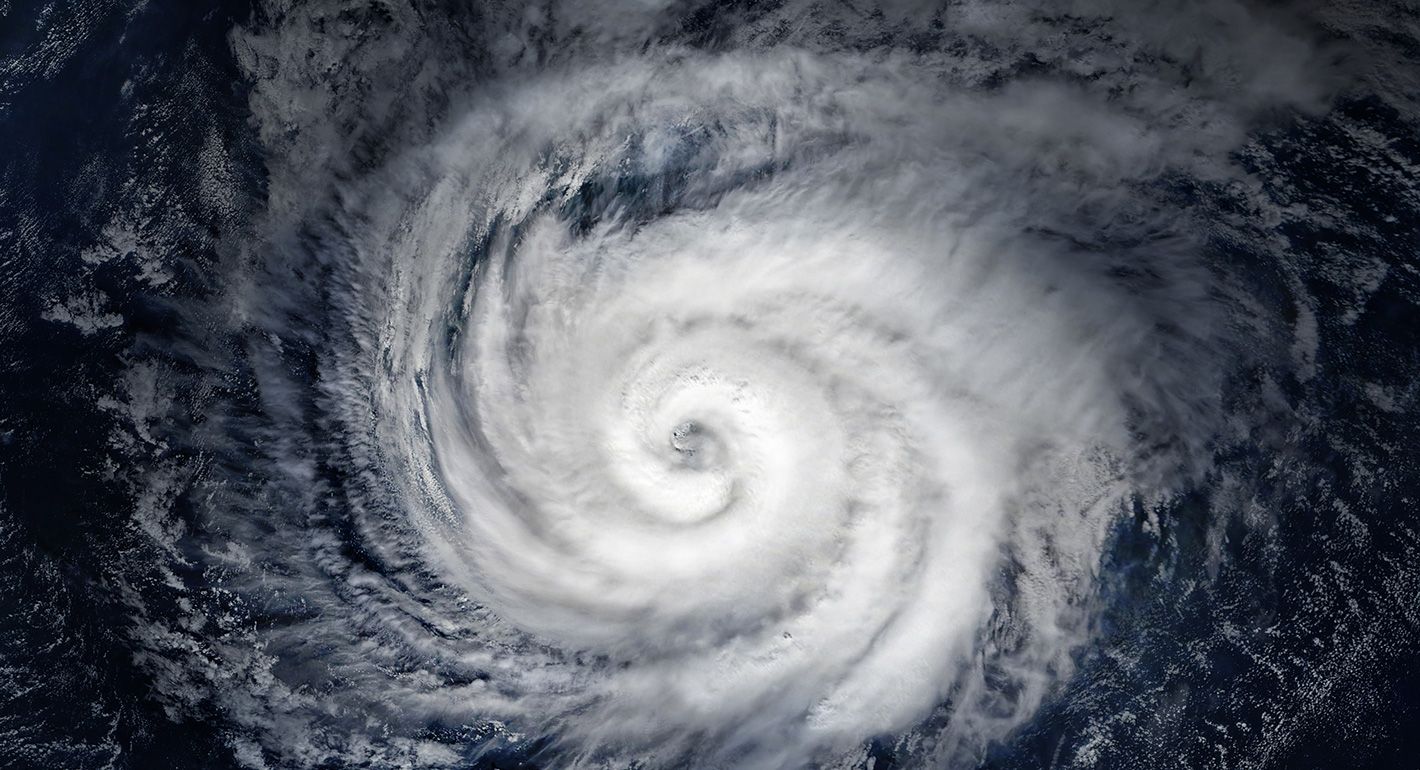

Federalism is beneficial for disaster-prone states. Spreading the risk and cost of disasters across the entire country allows the United States to maintain a response system that includes not just funding, but also important capacities such as weather monitoring and trained staff who can deploy to disaster-affected regions. With a reduced or nonexistent federal system, states will have to create their own programs for managing and recovering from disasters. Coastal states have fewer than ninety days until hurricane season begins.

No state currently has the capacity to absorb the capacity or function of the federal government in disaster recovery. Shuttering programs that provide help directly to state and local governments will hit hardest in places that are already struggling, where the government currently doesn’t have the resources to rebuild schools, repave roads, or repair water treatment facilities.

The sudden loss of a federally backed disaster ecosystem could have dramatic consequences—quickly. People will suffer lifelong economic setbacks as they lose assets. Some may become homeless. Housing prices in already stressed urban centers will go up, as those who cannot or do not want to rebuild move away. Kids won’t be able to go to school or will be pushed into overcrowded schools. Unrepaired infrastructure will slow economic activity, kicking of a cycle of reduced incomes, lower tax revenues, and fewer services that support people and their communities. People with the fewest resources will have the most limited choices about how and where to live in this new landscape. The philanthropic sector will be heavily burdened in picking up the slack.

If the administration makes good on its promise to rapidly defund the federal disaster system, states such as Louisiana, Florida, and Texas will be at the front lines of the transition to a bleak post-disaster future.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.