The rising pace and cost of disasters is cause for alarm, both because of the likelihood of major disruption in so many people’s lives, and because of the potential for systemic failures in the housing and insurance markets that could lead to wider, global economic shocks.

{

"authors": [

"Sarah Labowitz",

"Debbra Goh"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Climate Disasters and Adaptation",

"Climate Mobility"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "SCP",

"programs": [

"Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Climate Change"

]

}

Homes destroyed by the Eaton Fire in Altadena, California, on January 10. (Photo by Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images)

The California Fires Could Upend the U.S. Disaster Recovery System

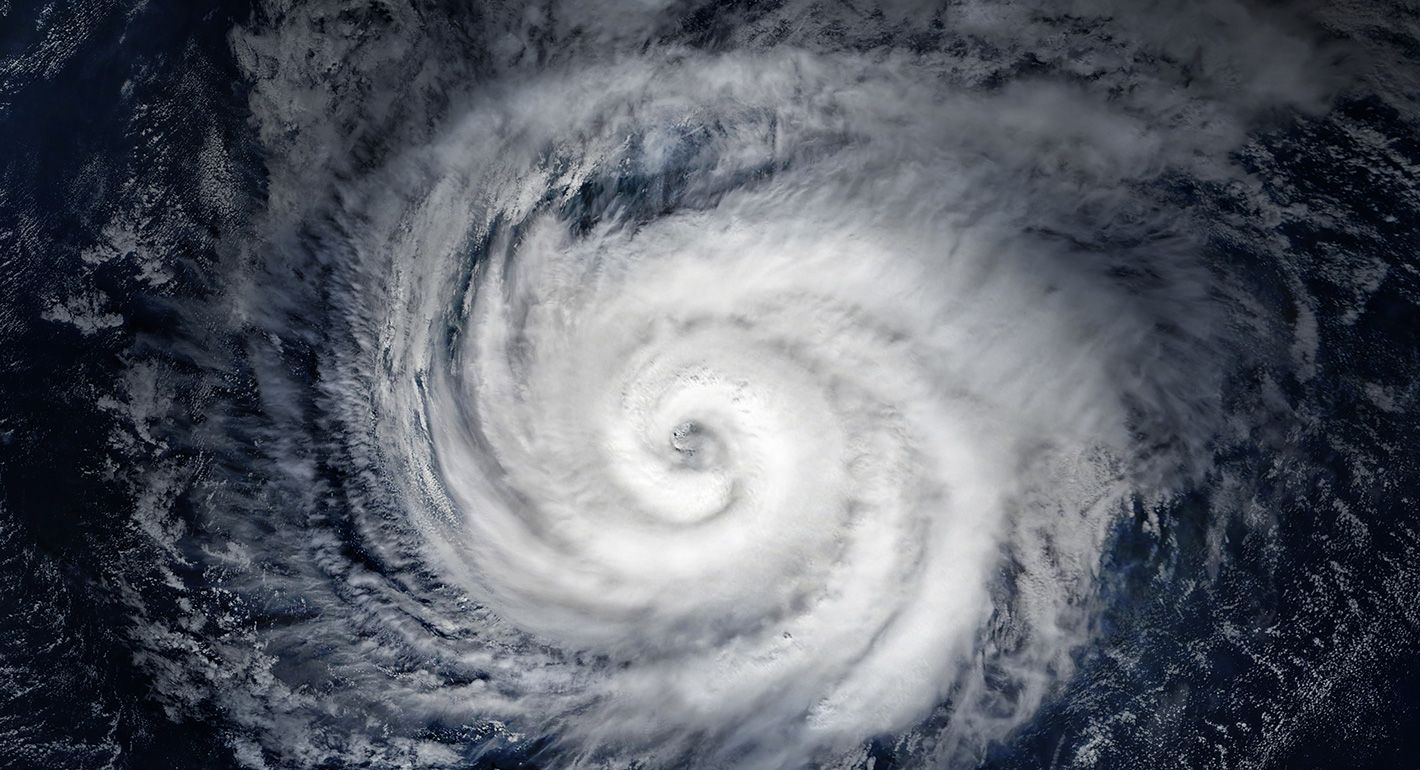

Hurricane-strength fires in dense, urban areas are a game-changer for an already fragile federal recovery structure.

The fires in Los Angeles are a stunning, can’t-look-away disaster. In press conferences on Thursday, emergency management officials increased the estimated number of destroyed structures to more than 10,000. The Palisades Fire and the Eaton Fire are already the two most destructive fires to hit Los Angeles—and they remain mostly uncontained. Ten people have died, and thousands of acres continue to burn. Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna described some areas of the city as looking “like a bomb was dropped in them.” The fire has destroyed the houses of celebrities and working-class Californians alike, many of whom have been dropped from fire insurance policies since 2020.

Over the past decade, wildfires typically have hit more rural areas, resulting in higher-than-average payouts from the federal government to a relatively small number of homeowners. Historic spending on wildfires pales in comparison to that for hurricanes, which are the biggest and most expensive kind of disaster affecting individual households in the United States. But with the potential scale of damage from these fires, we could be witnessing a tipping point for disaster recovery funding, at a moment when our federal recovery system is as fragile as ever.

In August of last year, we published the Disaster Dollar Database, a collection of federal spending data on disaster recovery for the two biggest agencies involved in recovery for individuals and communities, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). From 2015 to mid-2024, there were fourteen major wildfires for which federal recovery funding was distributed.*

(You can read more about the process for developing the Disaster Dollar Database here and look at the data here. To learn more about wildfire recovery spending, click on the “Incident Type” tab in the data.)

FEMA is the first line of response for individuals who have survived wildfires. For the past decade of major wildfires, the average household received $9,578 from FEMA through its Individuals and Households Program (IHP), which is designed to kickstart individual recovery with relatively quick grants that supplement recovery funds from insurance, charitable organizations, and private resources. That’s much higher than the overall average for disaster survivors, which is $5,693. In total, FEMA spent $270 million through IHP on major wildfires from 2015 to mid-2024, out of $12.7 billion in IHP funds across major disasters.

But wildfires have a unique disaster profile: they typically hit less populated areas but completely devastate structures. Wildfires represent a relatively small portion of overall applications for disaster assistance over the last decade.

For a major hurricane, millions of people can apply for assistance across the affected area. After Hurricane Irma in 2017, more than 2.6 million people applied for FEMA assistance in Florida. Only a fraction of applicants are eligible (29 percent in the case of Hurricane Irma), and most people do not apply for total loss—they may have experienced a damaged roof or several inches of water in one part of the house, or they may have expenses related to a long-term power outage. In contrast, the highest number of people to apply for assistance after a wildfire is 27,057 after the 2018 Camp Fire, which wiped out the communities in and around Paradise, California.

The question now, as damage assessments are underway, is whether we’re headed for a new kind of fire scenario that’s closer to a hurricane in scale. Data from the nonprofit Texas Appleseed shows that Hurricane Helene impacted 301,451 homes in Florida, of which 41,000 experienced at least “major” damage and 3,312 “severe” damage. By comparison, as of publication time, 10,000 structures have been destroyed in the ongoing wildfires, and an estimated 62,000 structures are threatened.

In addition, Angelenos will be stepping into a recovery landscape without a strong insurance market. Like their counterparts in hurricane-plagued states, many Californians have seen their home insurance policies dropped (or likely will soon), and a state-backed insurance mechanism is already stretched beyond its limits. Disaster recovery in the United States was designed as a three-legged stool supported jointly by public and private insurance, grants, and loans. Without insurance, the ecosystem won’t function, and whole communities will fail to recover. In July, State Farm reportedly dropped approximately 1,600 policies for homes in Pacific Palisades. That neighborhood has a median home price of $3.1 million—more than ten times that of Paradise—which could further strain the system with astronomically expensive costs to rebuild.

In addition to individual recovery, this level of damage will require significant financial recovery assistance for public spaces across a wide geographic area. FEMA’s Public Assistance Program reimburses jurisdictions for the costs of rescue efforts, clearing debris, and repairing public roads and buildings, including schools. FEMA has spent a total of $4.8 billion on this type of recovery assistance across the fourteen recent wildfires we studied, for an average of $342 million per fire—in contrast to an average of $985 million per hurricane over the same period.

HUD’s Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program is another important source of community recovery. This funding usually prioritizes programs in low- and moderate-income communities, and it’s especially crucial for those with lower incomes. CDBG-DR is a lifeline for communities that are underinsured or that simply don’t have the private resources to rebuild family homes. In total, Congress appropriated just over $2 billion in CDBG-DR for wildfires from 2015 to 2023, the largest chunk of which was $541 million for the 2018 California Camp Fire. But that pales in comparison to the CDBG-DR amounts for hurricanes: After Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, Puerto Rico received more than $9 billion in CDBG-DR funds, and Texas received more than $6 billion after Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Unlike FEMA, HUD has no permanent program that Congress can routinely fund, so money can take a long time to arrive. From 2015 to 2023, it took an average of 401 days from the beginning of a wildfire incident for Congress to appropriate and HUD to allocate the funds.

Gridlock in Congress last year caused long delays in CDBG-DR appropriations. The down-to-the-wire budget negotiation that prevented a government shutdown included $110 billion for disaster recovery, including CDBG-DR funding for disasters that had happened eighteen months earlier. (We broke down the December 2024 disaster budget here.)

The disaster recovery system in the United States is most accustomed to responding to major water events, defined by widespread impact and partial structural damage. We have not yet seen a truly large-scale fire event, with tens of thousands of people applying for assistance for total structural loss not covered by insurance. After the fires subside and damage estimates start to roll in, we’ll be watching three trends:

- How many people apply for FEMA assistance for major uninsured losses

- Whether conspiracy theories or politicized information poisons the recovery effort, particularly by sowing distrust in government emergency managers

- Whether the new Congress will be able to act more quickly than the previous one in providing CDBG-DR funding

Disasters can spur adaptation—including not rebuilding in some places—to a climate that’s already on our doorstep. Disasters can also inspire personal, governmental, and financial flexibility that we can use to adapt, relocate, and build for the future. Hurricane-strength fires like the ones currently burning are a step change in our climate reality and will require radically new ways of thinking about mitigation and recovery—and funding for both.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.

*Correction, January 10, 2025: This sentence originally stated that the fourteen wildfires received both FEMA and HUD funding. Two did not receive HUD funding.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Emissary

- With the RAISE Act, New York Aligns With California on Frontier AI LawsCommentary

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

- The Trump-Modi Trade Deal Won’t Magically Restore U.S.-India TrustCommentary

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- Federal Accountability and the Power of the States in a Changing AmericaCommentary

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

- Trump Wants “Peace Through Construction.” There’s One Place It Could Actually Work.Commentary

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan