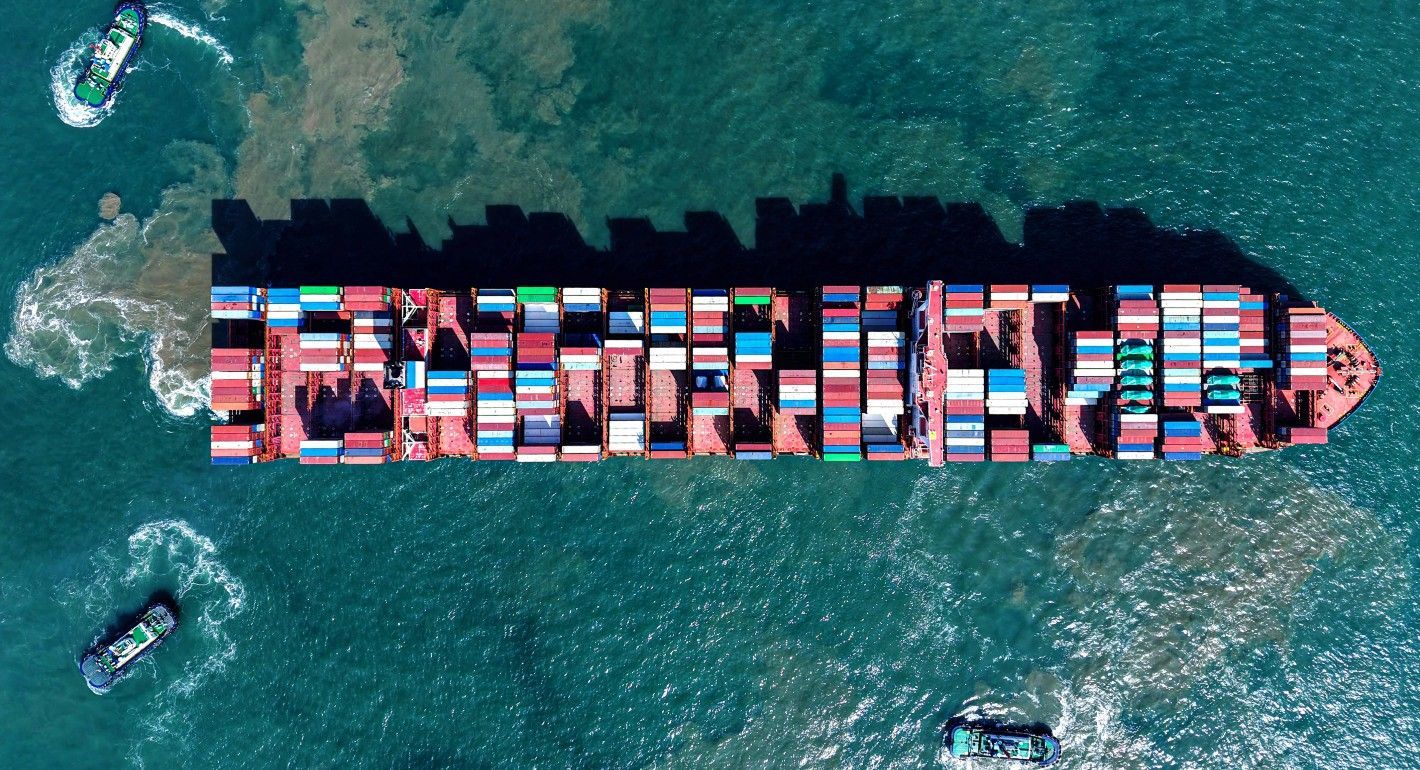

In August, the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump took the unusual step of issuing a joint statement from four cabinet secretaries declaring U.S. opposition to a new global framework to cut greenhouse gas emissions from the shipping industry. The pact, known as the Net-Zero Framework, was developed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO)—the UN agency that regulates global shipping—and has been nearly a decade in the making. It would set binding greenhouse gas targets for an industry that transports nearly 90 percent of goods traded between countries, accounts for 3 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and would rank as the world’s sixth-largest polluter if treated as a country.

The deal had been on track for formal adoption next week, with broad backing from the shipping industry and IMO member states. Its fate is now unclear, especially after Washington signaled it may bring its weapon du jour—tariffs—to the fight, threatening retaliation against countries that vote for the deal. Washington’s sudden opposition not only threatens to derail years of negotiations but risks sidelining the United States from a global energy transition already worth hundreds of billions of dollars as rivals in Europe, Asia, and Latin America move to shape it.

An Unlikely Coalition

The path to this point reflects a decade of unlikely leadership and industry dynamics. Calls for urgent action emerged during the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement negotiations and were led by the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the third-largest flag state and also highly vulnerable to rising sea levels. For the Marshall Islands, this was an extraordinary step, as its shipping registry is a major source of revenue for the government, which at the time outsourced most administrative functions to a Virginia-based private firm.

Shipping is inherently transnational, with vessels often owned, registered, and operated across multiple jurisdictions. Tony de Brum, then foreign minister of the Marshall Islands, illustrated this point in June 2015 when he called for a “global solution” for the sector, noting that “if one refuses to register a particular vessel or platform in one registry, they simply jump to another registry.” His intervention helped shape the Paris negotiations, where countries agreed that, rather than leaving global emissions regulations to national pledges—the bedrock of the Paris Agreement—shipping required an industrywide framework under the IMO.

The IMO published its first decarbonization strategy in 2018 that required at minimum a halving of 2008 emission levels by 2050. Although this fell short of Paris commitments, it marked the first time any global sector had agreed on an emissions reduction pathway. The strategy also included a mandatory review every five years, which soon became the focal point for pressure from shipping industry groups and climate-vulnerable states to set more ambitious targets. This pressure led to the creation of the Getting to Zero Coalition, backed by major industry players such as Maersk.

The push for tougher targets was not just about climate altruism. It was also shaped by commercial realities. Companies wanted to ensure their next generation of vessels would not risk becoming stranded assets as the world moved toward a low-carbon future. Maersk made the point explicit after the IMO’s 2018 strategy, stating, “Given the 20–25-year lifetime of a vessel, it is now time to join forces and start developing the new type of vessels that will be crossing the seas in 2050.” At the same time, major retailers such as IKEA, Amazon, and Unilever were beginning to scrutinize the carbon intensity of their supply chains, giving first movers another reason to get ahead of the curve.

In 2023, the IMO committed the sector to reach net-zero emissions by midcentury, with interim targets along the way. The first, in 2030, includes not just sectorwide emission reductions, but also a target for uptake of “zero or near zero” fuels across the global fleet. In April 2025, members agreed on the measures to deliver on that goal, including a global fuel-intensity standard backed by fees for noncompliance, with proceeds channeled into a new Net-Zero Fund for clean shipping. Some key details remain unresolved, including how revenues from the fund will be distributed and which fuels qualify as “zero” or “near-zero.” These details will determine whether the framework delivers genuine emissions cuts or simply creates new loopholes. Nevertheless, the Trump administration is seeking to derail the commitment.

The U.S. Opportunity

Although the Net-Zero Framework was designed to clean up shipping, its impact would have stretched far beyond the maritime sector. Most ships today run on bunker fuel, a heavy oil that is among the dirtiest sources of energy. The leading clean alternatives are hydrogen-based fuels such as ammonia and methanol. These fuels serve multiple sectors at once: They can power vessels, but they are also critical inputs for fertilizer and chemicals, and hydrogen itself can supply high-temperature industrial heat. For shipping companies, the priority is certainty about future fuel choices. The International Chamber of Shipping, which represents most of the global fleet, backed the framework in April and urged the IMO to “send a clear signal to industry and provide the incentive needed to produce these cleaner fuels.” By locking in demand from shipping, the framework is poised to accelerate the use of these fuels across the wider economy.

That same call for certainty has been echoed in Washington. In September, the Chamber of Shipping of America testified in support of the Renewable Fuel for Ocean-Going Vessels Act, a bipartisan proposal to extend renewable fuel credits to marine applications and help close the cost gap between conventional and cleaner fuels. U.S. shipowners, the chamber stressed, are “fuel agnostic” but need clear rules, infrastructure, and incentives to invest—the very principles the IMO Framework seeks to establish. Yet even as U.S. industry and bipartisan lawmakers line up behind this approach, the administration is working to block the global framework that would deliver it.

The irony is that while the low-carbon hydrogen market is still nascent, the United States was well-positioned to lead its development. By the end of 2024, the Hydrogen Council estimated global project announcements had reached $680 billion, with North America accounting for about $96 billion of that pipeline—the third-largest regional share. When it came to projects actually moving forward, North America dominated, with more than 90 percent of global low-carbon hydrogen capacity. This lead was supported by former president Joe Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, which together offered grants for regional clean hydrogen hubs, loans for innovative projects, and a production tax credit. By the end of the Biden administration, at least 164 U.S. hydrogen projects had been announced. But rising costs and ongoing policy uncertainty—including the Trump administration’s recent termination of federal funding for two West Coast hubs—have cast doubt on how many of those projects will move forward.

In addition, despite generous incentives, developers have warned that the industry needs a clearer demand signal to unlock bankable, project-level investment. Hydrogen today is mostly bought on spot markets, without the kind of long-term contracts that typically underpin the large-scale debt financing of conventional energy projects. Offtake agreements—the contracts that guarantee a buyer for a project’s output—are rare for hydrogen, and those that exist are often short-term and pegged to other energy commodities such as electricity or natural gas. That volatility leaves developers without the steady revenues needed to attract investors. The Biden administration’s demand-side support program, launched in 2023 to help provide offtake certainty and establish a market price for clean hydrogen, has since been pulled back. That makes the IMO’s Framework the only remaining credible demand signal—one that could offer the predictability needed to scale hydrogen-derived shipping fuels and lower costs across other sectors.

The Course Ahead

Nearly a decade ago, countries such as China, India, and Brazil resisted ambitious IMO emissions targets. Today, they are among the biggest investors in the hydrogen infrastructure that the Net-Zero Framework would help unlock.

China is leading the way. In June, the vessel Anhui, powered entirely by ammonia, completed its maiden voyage, demonstrating what the future of shipping could look like. India launched its National Green Hydrogen Mission in 2023, with pilot projects for ammonia refueling and export terminals already underway in the state of Gujarat. In Ceará, Brazil is developing a major green ammonia project—a venture between Chinese and Spanish companies—designed to supply both shipping and fertilizer markets.

The IMO’s proposed Net-Zero Framework is the product of a decade of unlikely leadership and painstaking diplomacy, with a vulnerable island nation taking on big powers, an industry once skeptical now demanding certainty, and countries that long resisted now investing in the fuels to make it real. Even if the Trump administration has no interest in a historic climate deal for a global sector, the United States has clear economic interests in not letting rivals sail ahead and capture the hydrogen economy without it.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.