The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

{

"authors": [

"James M. Acton"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "NPP",

"programs": [

"Nuclear Policy"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States",

"China",

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Nuclear Policy",

"Security",

"Defense"

]

}

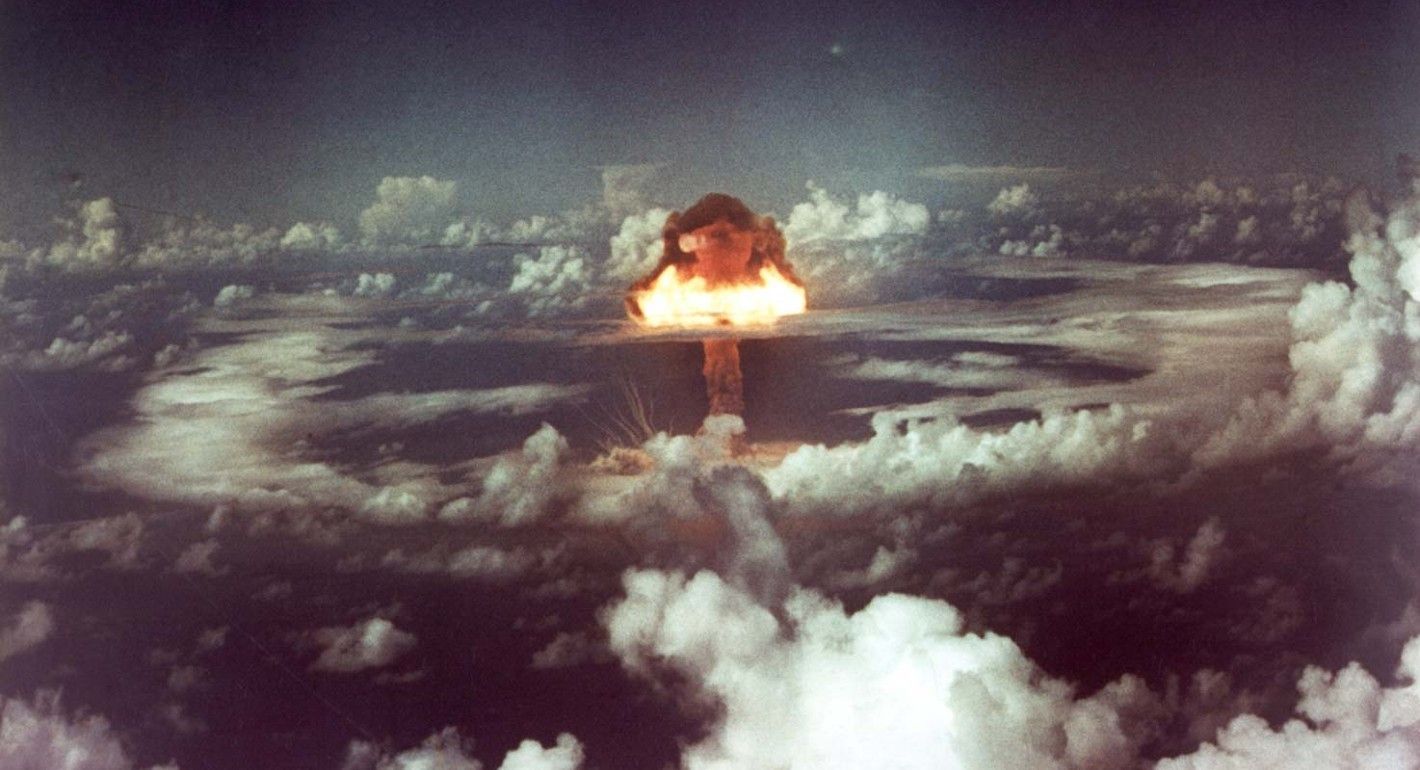

The Ivy King test, 1952, Enewetak Atoll. (Courtesy of the National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Site Office via Wikimedia Commons)

Sometimes good policy can be as simple as not nuking yourself in the foot.

On September 23, 1992, shortly after 3 p.m., the ground 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas shook violently as an underground nuclear weapon detonated, releasing as much energy as 5,000 tons of TNT. That explosion was the last nuclear test conducted by the United States. Thirty-three years later, President Donald Trump appears to want to conduct more.

Last Thursday, Trump announced on Truth Social that “because of other countries testing programs, I have instructed the Department of War to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis.” In an interview the next day, Trump doubled down: “I don't wanna be the only country that doesn’t test.”

Resuming the testing of nuclear weapons would be a step toward nuclear anarchy. Fortunately, Trump has a way out. Exploding warheads isn’t the only way to “test” nuclear weapons. The United States could test components or subsystems (a possibility alluded to by Energy Secretary Chris Wright), or it could flight-test nuclear-capable missiles. (Indeed, it does both these already.) Trump should capitalize on this ambiguity by announcing a path forward that doesn’t involve detonating a nuclear warhead.

Central to Trump’s justification for testing is his confident assertion that China and Russia are doing so. The U.S. intelligence community, however, appears to have a more nuanced view. In 2024, the State Department reported that Washington was “concerned” that Beijing and Moscow were testing—a statement that stops short of an unambiguous accusation.

The intelligence community’s apparent uncertainty may be surprising. After all, doesn’t nuclear testing involve humungous explosions that ought to be easy to detect?

Not necessarily.

Nuclear testing can involve tiny “ultra-low” yields, equivalent to igniting fractions of an ounce of TNT. In such “supercritical” experiments—which could be conducted to check the safety of existing warhead designs—nuclear material is compressed just enough to allow a chain reaction to occur for a moment. It’s like striking a match just hard enough to cause a tiny flame that fizzles in an instant.

The problem facing the intelligence community is not so much detecting supercritical experiments but distinguishing them from subcritical experiments. Subcritical experiments—which could be conducted to understand how nuclear material changes as it ages—involve compressing nuclear material but stopping just before a nuclear chain reaction begins. This time, the match sparks but does not quite catch.

The distinction between supercritical and subcritical experiments may seem arcane—and, in fairness, it is. The experiments use similar, perhaps identical, equipment, which makes it extremely tricky for rivals to differentiate between them. It’s one thing to notice someone striking matches; it’s another to see whether they’re doing so just hard enough to create the most evanescent of flames. But the difference matters because, for Washington, it defines the point at which an experiment involving nuclear material becomes a nuclear test. The U.S. government does not consider subcritical experiments to be nuclear testing—it conducts them itself. Its concern is that Chinese and Russian experiments cross to just the other side of the criticality line.

Yet, even if China and Russia are conducting ultra-low-yield nuclear tests, the costs to the United States of resuming testing itself will outweigh the benefits.

Ultra-low-yield testing probably won’t help China and Russia make more effective nuclear weapons. In 2012, the U.S. National Academies concluded that “it is unlikely that [such] tests would enable Russia to develop new strategic capabilities outside of its nuclear-explosion test experience.” China, with less experience in nuclear-weapon design, is even less well-placed to capitalize on ultra-low-yield testing, with the National Academies stating that “it is not clear how China might utilize such testing in its strategic modernization,” which is another reason to question whether Beijing is engaged in this activity.

Meanwhile, there is no technical reason for the United States to test nuclear weapons of any yield. It can ensure the safety and reliability of its current stockpile without detonating existing warheads, and it could even design new warheads based on previous tests (whether or not that’s a good idea).

Indeed, for many supporters of nuclear testing, the primary reason to test isn’t technical—it’s political. One advocate told the Washington Post that the United States needs to “do something to demonstrate that we’re not going to be intimidated or coerced by these autocrats in Beijing, Moscow and Pyongyang.” If this is the goal, ultra-low-yield testing—which isn’t exactly Trumpian, anyway—wouldn’t suffice. It’d be necessary to make the ground shake, equivalent to throwing the lit match onto a sea of gasoline.

This step would open Oppenheimer’s box (sorry, Pandora). If the United States conducts a full-scale nuclear test, China, Russia, and North Korea will likely follow. In fact, they may even precede the United States, given the year or three required to prepare a test at the facility formerly known as the Nevada Test Site. Moreover, a Chinese test will almost inevitably spark an Indian test, and an Indian test will prompt a Pakistani one. All these states will want to detonate ground shakers too.

Such a world would be more tense and less secure. Any resumption of testing would, in part, reflect increased international tensions, but it would also exacerbate them. Leaders would believe—correctly—that rivals were seeking to intimidate them through testing and take steps to show those rivals have failed. Those steps—nuclear tests, exercises, or threats, say—would risk driving tensions higher.

To make matters worse, other states could make more use of testing data than the United States. The United States conducted over 1,000 nuclear tests previously, while Russia has conducted 715 and China a mere forty-five. As a result, U.S. weapon scientists almost certainly understand nuclear-weapon physics better than their Russian and Chinese counterparts. A restart of full-yield testing will level the playing field, allowing Russia and particularly China to develop new types of nuclear weapons.

Sometimes good policy can be as simple as not nuking yourself in the foot. Trump has an out. He should take it.

Proliferation News is a biweekly newsletter highlighting the latest analysis and trends in the nuclear policy community.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan