Hostility toward the United States is rising among the Egyptian protestors, as U.S. officials urge Mubarak to allow an orderly transition to democracy. Michele Dunne explains that while the Obama administration’s initial response was inadequate, Washington has gradually improved its rhetoric as the crisis has escalated. The United States must clearly signal its strong support for democracy and engage with the Egyptian government, opposition, and civil society to play whatever role it can in supporting bottom-up democratic change.

- What is the current situation in Egypt?

- How has Washington reacted to the unrest?

- How effectively has the Obama administration responded to the crisis?

- What is the history of U.S.-Egyptian relations?

- How important is Egypt in U.S. foreign policy?

- What should the Obama administration do moving forward?

What is the current situation in Egypt?

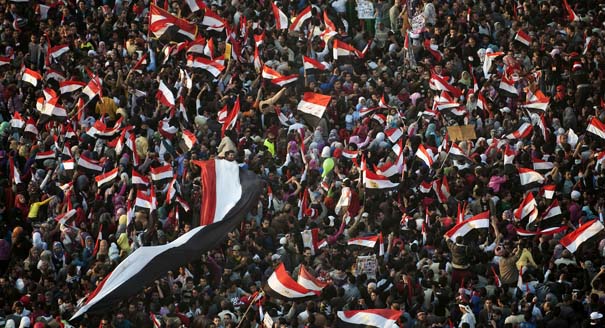

Protests have been growing in Egypt since January 25 and they show no signs of abating. In fact, they seem to be growing larger. Protests are occurring in a number of Egyptian cities with the largest oens seen in Tahrir Square in the center of Cairo.

The protestors are escalating their demands, with the primary call is for President Mubarak to step down. But they are also calling for dissolution of parliament and for a constitutional assembly to be created to rewrite the constitution to pave the way for free and fair elections.

The Egyptian government has to respond to these demands one way or another. So far, their response has been very limited and basically just changed the cabinet.

How has Washington reacted to the unrest?

The U.S. response to the demonstrations in Egypt has been evolving since they began.

From the very beginning, there have been a few consistent principles that the United States has articulated. One of them was that no violence should be used against the demonstrators, that the demonstrators themselves should behave peacefully, and that the universal rights of the Egyptian people should be respected.

What has evolved is what the United States has said about what should happen next. Initially, the U.S. administration was using talking points such as the “need to reform” and so forth. They have gradually moved to talking about a transition.

Now they are talking about an orderly transition to real democracy in Egypt. Secretary Clinton, in a number of interviews, has spelled out a little about what is meant by democracy. Certainly, free and fair elections are part of that.

How effectively has the Obama administration responded to the crisis?

The U.S. response to what has happened in Egypt, initially, was inadequate. Some of the rhetoric that the United States used in the first few days was very much out of touch with what was going on in Egypt. At first the United States was saying that Egypt was stable and the Egyptian government was responding to the demands of its citizens, which it really was not.

Then the United States started talking about things like reform. Frankly, the time for reform was several years ago. Now, we’re getting reform, we’re getting bottom-up change instead of top-down reform.

The United States has talked about national dialogue but that is sort of a discredited idea in Egypt, because the government held national dialogues with civil society that never went anywhere.

The United States has been gradually improving its rhetoric and position on the situation in Egypt and is getting closer to reality. One thing the United States has to look out for is that events in Egypt are changing and as the demonstrations continue, the demonstrators are beginning to escalate their demands. They’ve gone from asking Mubarak to step down to now saying they want to prosecute Mubarak—which would be an ugly situation.

I think it would be best for all involved if the United States were to urge a quick resolution of this issue and not to let these demonstrations play out. The demands will only escalate and the prospect for violence rises as time goes on.

What is the history of U.S.-Egyptian relations?

The United States and Egypt have had strong relations since the mid-1970s, at which time Egypt made a strategic shift from an alliance with the Soviet Union to one with the United States. Egypt also made the decision to pursue peace with Israel and reached a peace treaty with it in 1979.

Since then Egypt has been a major regional ally of the United States. They have close military relations and Egypt receives an extensive aid package. At one time, Egypt got over $2 billion a year in aid. Nowadays they get a total of about $1.5 billion, most of that is military aid.

How important is Egypt in U.S. foreign policy?

Egypt is an important element in U.S. policy in the Middle East. It was the first Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel and, ever since then, it has had a special role as a partner of the United States in working with the Palestinians and other parties in the Middle East to make peace with Israel.

Egypt also has a strategic location. It controls the Suez Canal, which is a key chokepoint for both commercial and military transit of vessels.

The Egyptian government continues to play a role in regional diplomacy and peacemaking, but frankly Egypt has become so preoccupied with its domestic affairs—with the problem of succession after the 30 year presidency of Hosni Mubarak, its economic problem, and with growing social, human rights, and political problems—all of these things have taken up most of the energies of the Egyptian governments in recent years. They simply are not playing the kind of extensive regional role that they once did.

What should the Obama administration do moving forward?

Moving forward, it’s very important for the U.S. administration to make it clear that it supports the legitimate demands of the protestors, but also to advocate for a peaceful transition—and one to a real democratic order. The whole situation is very difficult and fraught with risks and there are no guarantees here.

But it’s important that the United States stands for its principles. These protestors are demanding democracy—this is not a radical revolution of some kind, it’s not an Islamist revolution.

At this point it’s not a very anti-U.S. kind of revolution or protest. What the protestors are asking for is what the United States itself says it supports—democracy. It is important that the United States support that and stay engaged—both with the Egyptian government and with the opposition and civil society in Egypt—to play whatever role the United States can in seeing that Egypt makes a successful transition to democracy.