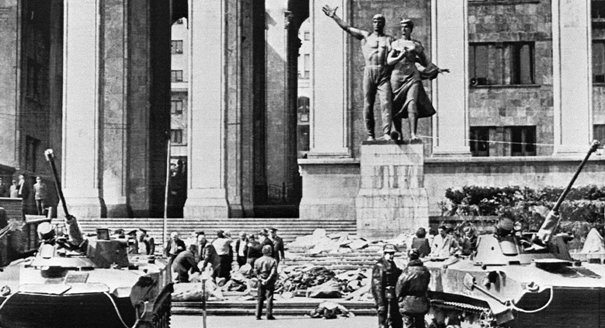

Georgia is marking the anniversary of the killing of protestors in Tbilisi on April 9, 1989. It is a reminder of wounds that are all too recent, of anger and trauma that are just below the surface.

The country still lives by its own rules. Just as Ukraine is in crisis and agreements with the European Union are closer than ever, political feuds continue.

The good news is that there is a clear political consensus on a European path. In June the country will meet a major landmark, by signing an Association Agreement with the European Union. At the same time, the long bruising electoral cycle will finish, when local elections are held.

The trouble is it is not clear at the moment who is steering the ship. Georgia is a country with no fewer than four leaders at the moment. The leader with the constitutional power is Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili. He is clearly capable but at 32 lacks the experience to lead a country through difficult times and lashes out at perceived enemies.

Then there is his patron and predecessor Bidzina Ivanishvili who is evidently still the main guide behind the scenes, despite having stepped down as prime minister a few months ago.

The recently elected President Giorgi Margvelashvili is head of state but lacks real power and was recently criticized by the man who first nominated him, Ivanishvili for some of the decisions he has made.

And finally there is the elderly Patriarch Ilya II, who is by far the most popular person in Georgia. The Patriarch himself is a skilled politician and figure of unity but the increasing role of the church is bringing to life some of the obscurantist nationalist views Georgia last heard under its first (and disastrous) President Zviad Gamsakhurdia more than 20 years ago.

One symptom of that was the ugly scenes last week as the media reported—falsely—that local Armenians were queuing up at the Russian interests section in the Swiss embassy in Tbilisi to get Russian passports. They were in fact getting seasonal work visas, but even as the foreign ministry denied the reports, parts of society vented anti-Armenian prejudices which are all too prevalent.

So this is not a good time at all for the continuing legal investigation of officials from the former government of the United National Movement.

The United National Movement, still chaired by former President Mikheil Saakashvili, does itself no favors. It lobbies against the government in Western capitals. Its members label all prosecutions as politically motivated, and refuse to come to terms with the more abusive part of their legacy. They do this, even though evidence continues to mount up of alleged human rights abuses and suspicious financial flows.

It was telling how the U.S. State Department human rights report did not find much to criticize in the trial of the former enforcer of the old regime, Vano Merabishvili, while noting an overall improvement in the human rights situation.

But of course it is the government that sets the climate. And the decision to summon both Saakashvili (long-distance) and former Security Council Chairman Giga Bokeria for questioning at this particular moment has Western diplomats in Tbilisi tearing their hair. It is the last thing Georgia needs just at the moment.

June and the European Association Agreement will be another moment for Georgia to look forward, not backwards. The government will need to ask for money to implement the EU economic approximation project—which gives Brussels more leverage. But the country cannot afford any more fratricidal quarrels, when Russia is breathing fire just over the horizon.