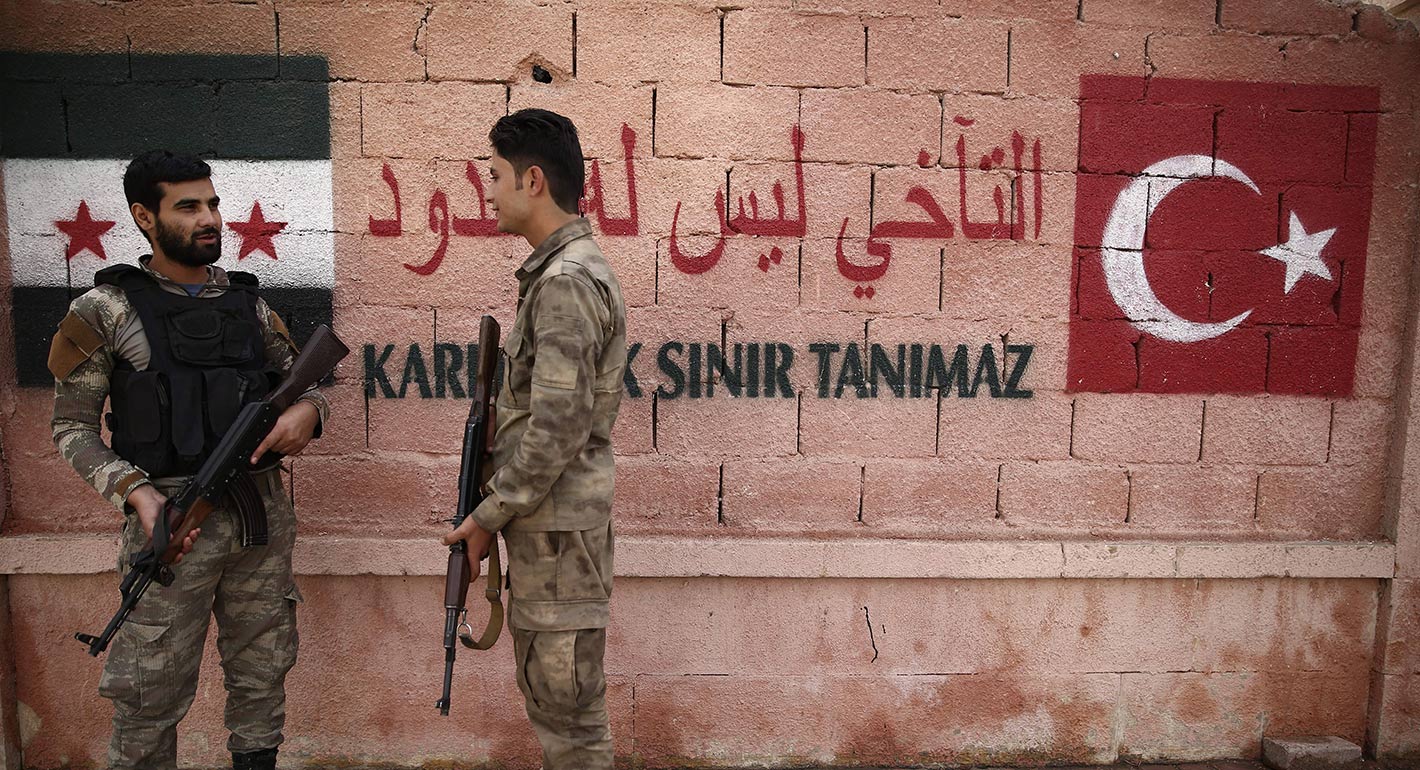

Turkey’s military action in Syria has damaged its relationship with the EU

Turkey’s relationship with the EU was already fragile, since President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s constitutional reform ended up dismantling the country’s rule of law. But Ankara’s military incursion in Syria has made things worse. Most European countries see it as a domestic political operation, with the fight against the so-called Islamic State taking second priority. Forcing a domestic consensus on terrorism will temporarily silence opponents and dissenters within Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development party (the AKP).

But the EU’s unanimous condemnation, and several EU countries’ arms embargoes, will not deter Ankara. They could even have the exact opposite effect, given the regime’s tight control over Turkey’s judiciary and media. Generally speaking, Turkey’s ultra-nationalist trajectory—designed to consolidate the president’s dominance over domestic politics—has by its very nature a corrosive effect on relations with the EU.

The deal to manage the influx of refugees is under stress

The EU has set up a €6.0 billion facility for humanitarian support for Syrian refugees in Turkey. The projects were spread over four years, and are nearing completion. It was the biggest-ever such operation and won praise from Syrian refugees, host communities, and the EU’s partners in Turkey (the Agency for Emergency Situations, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, and Turkish Red Crescent).

But Turkey’s leadership has harshly criticized this massive humanitarian program, in part because the money was not paid in bulk to the government’s accounts (this is not allowed under EU rules). Ankara has also been chagrined by unfulfilled promises made by the EU in 2016 about visa liberalization, upgrading its customs union with Turkey, and the accession process.

If the EU can reach an agreement with Turkey’s leaders, the current humanitarian framework could be extended or adapted.

How Russia and the United States affect the dynamic

After a failed coup in July 2016, Turkey’s relations with Russia became much warmer. At first, this reflected the comfort that Ankara found in a relationship where—unlike the EU and the United States—its partner didn’t complain about rule-of-law issues.

Since Russia sold Turkey a supply of S-400 anti-missiles systems, the relationship has taken an entirely different dimension. In the West, Russia is seen as using Turkey to undermine NATO’s own missile defense architecture, and to drive a wedge between Turkey and other NATO members. Ankara’s pro-NATO proclamations will not do much to change this perception.

With the United States, Europe has a different problem. Washington has been unpredictable on issues where a strong transatlantic agreement would be decisive, such as the coalition fighting the Islamic State in northern Syria. This means that the transatlantic allies cannot send a consistent message to Ankara.

Where Turkey’s resurgent nationalism might end up

The resurgence of nationalist feelings is not just a side effect of the ever-present conspiracy theories in Turkey’s political debates. It is the result of the leadership’s alliance with Turkey’s far-right, ultraconservative Nationalist Movement party (MHP), and their growing influence as an anti-EU, anti-U.S. political movement. This has created an environment in which the pro-EU elements of Turkey’s political spectrum have been marginalized. The leadership now rests on a one-man-rule system—which is the exact opposite of EU standards.

But there is also a deeper trend. A substantial segment of Turkey’s population are uneasy with their country’s affiliation with the West, via NATO, the EU Customs Union, and the Council of Europe.

Perhaps this reflects a more general feeling that, in a post-Cold War environment, Turkey would be better served by stronger alliances with Russia and China and a looser relationship with NATO, placing it in a position equidistant to all the world’s big powers. If implemented, such a fundamental change in foreign policy would constitute a true watershed for Turkey. These are critical choices for Turkey to make. Yet seen from Brussels, they are not being made within a true democracy.

Can the EU regain leverage in its relationship with Turkey?

Given Turkey’s current domestic politics, it is doubtful that its leadership will heed any of the EU’s requests on rule of law, economic governance, or foreign policy. So far, Ankara’s needling of the EU seems to have paid off well domestically.

The real problem lies in the consequences for trade and finance. Turkey cannot do without three European anchors: its markets, capital (both short-term funding and foreign direct investment), and technology. It simply doesn’t have meaningful alternatives. But it is unclear whether Turkey’s leadership realizes that hostility with Europe and undemocratic governance makes it harder to resolve the country’s economic woes.

Reviving the EU-Turkey relationship

Counterterrorism is one area where the EU and Turkey should work together, as terrorists threaten both Turkey and the EU. It is a very delicate field, because it requires close and confidential dialogue in order to track jihadists, including those with EU passports.

However, the Turkish leadership’s hostile stance on almost all areas of cooperation with the EU may well make working together more difficult than in the past, especially if Ankara decides to send back European jihadists captured under its watch in Turkey and in northern Syria. The issue of jihadists who crossed over to Syria via Turkey with EU passports, and whose citizenship has since been revoked, is a very thorny one for both sides.

This comes on top of several statements by Erdoğan suggesting that Syrian refugees in Turkey could be allowed to go to Europe: "Whether or not we receive support, we will still care for our guests, however, we cannot handle everything. If we see no other solution, we will open the gates, and I think it is obvious which direction they would go."

Trade, and especially the modernization of the Turkey’s custom union agreement with the EU, which has been in effect since January 1996—whereby Turkey’s manufacturing industry is fully integrated to the EU—is the second most important field of cooperation. But here, too, the dismal state of Turkey’s governance creates a huge hurdle.

Direct investment is another vital field of cooperation, since Turkey needs capital and technology from EU firms. But the degraded political environment has cast a dark shadow over future developments. The decision by Volkswagen to freeze a €1.3 billion investment is a case in point. Unsurprisingly, the many political trials underway in the country have taken a huge toll on Turkey’s attractiveness as a business partner. Erasing rule of law may help domestically, but it certainly doesn’t pay off internationally.