Supporters of democracy within and outside the continent should track these four patterns in the coming year.

Saskia Brechenmacher, Frances Z. Brown

{

"authors": [

"David Whineray"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

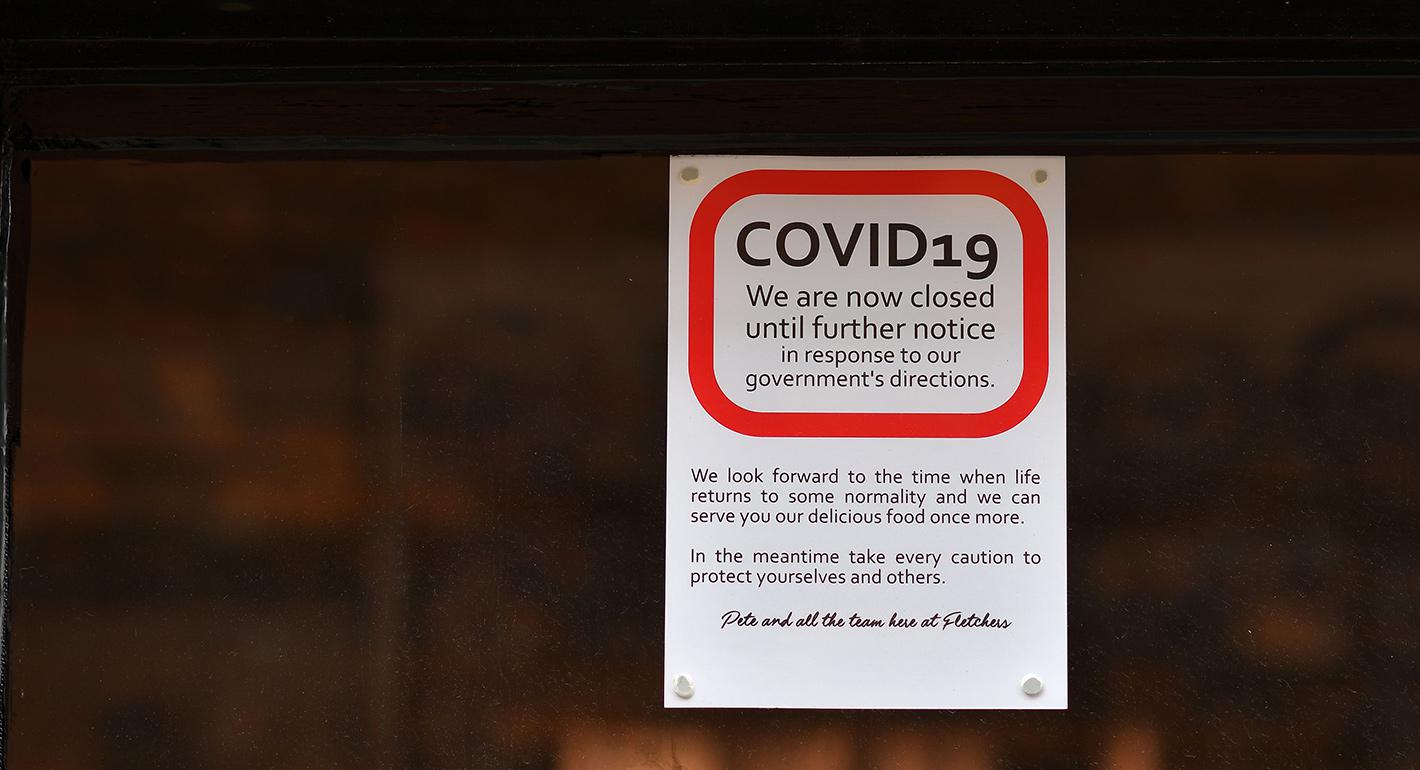

If the fight against coronavirus is a war—and there are also good arguments why such an analogy is misleading—what war is it?

Source: Independent

Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Emmanuel Macron have each now described the fight against coronavirus as a “war”. Trump describes himself as a “wartime president”. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has asked the public to support health workers, who he refers to as the "troops".

If the fight against coronavirus is a war — and there are also good arguments why such an analogy is misleading — what war is it? Which previous conflict provides the best historical insight into the dynamics we face today?

There’s a few previous wars to choose from. In terms of deaths, the Trump administration’s prediction of 100,000 American mortalities exceeds Vietnam. The map showing where Americans have stayed at home (the North East) and where they haven’t (the South) compares to the Civil War. The response of some European governments to the suspension of democracy in Hungary has echoes of the run up to 1939. But the closest parallel to today’s crisis is the First World War. In terms of both geopolitics and socioeconomics, 2020 is the new 1914.

Let’s take geopolitics first. In 1914, a combination of inept bilateral diplomacy and a lack of developed multinational structures hampered governments’ collective ability to manage the July crisis. Sound familiar? Much of this year’s diplomacy has been similarly bilateral, piecemeal and ad hoc. The lack of global governance (beyond a limited, advisory role for the WHO) has frustrated a coordinated global response.

The 1914 and 2020 crises share the same wider geopolitical backdrop too. Both hit as nationalism was prevalent within the Great Powers. Both occurred as tensions between challenging powers (Germany in 1914, China in 2020) and status quo powers (the UK in 1914, the US today) flared. Both took place as the established global order was fraying: the post-1945 rules-based international system today and the legacy of the Congress of Vienna in 1914. And both followed periods of rapid globalisation: just as today countries are adapting to social disruption and technological change, the citizens of 1914 saw a similarly shrinking world — new transatlantic liners, telephones, airships, electricity and automobiles combined with large-scale urbanisation and industrialisation.

Beyond politics, 2020 is also tracking 1914 psychologically, socially and economically. Financially, both crises are prolonged, brutal and expensive, requiring substantial increases in borrowing and national debt.

Socially, just as the First World War led to suffrage for women, a trade union movement and unemployment benefits, coronavirus is fuelling new ideas for radical reforms such as a basic minimum income, and is challenging a Western socioeconomic model that many see as having failed to monetarily value core workers or sufficiently invest in public services. Last weekend, Britain’s new Labour Party leader called for a “reckoning” when the crisis passes.

Psychologically, today’s governments — similar to their 1914 predecessors — were distracted as the crisis unfolded at a speed and extent for which they were unprepared. In the summer of 1914, the Cabinet of the then superpower (Britain) was focused on Ireland, not Germany; this year, the focus of the US President as Covid-19 arrived was re-election, not public health. Greater international leadership by London in 1914 and Washington in 2020 could have positively impacted both crisis. Instead, Downing Street in 1914 and the White House in 2020 each promoted unrealistic (religion-based) deadlines — the war being over by Christmas, the US re-opening at Easter — rather than preparing public expectations for the long haul.

Glance through Twitter today and you will see a multitude of tweets on what people plan to do when things “go back to normal” after this crisis passes. People in 1914 talked of the same. But the world never did return to how it was before the Great War. 1914 was the defining year of the last century, triggering revolution in Russia, the decline of Empire, the United States’ global emergence, and the creation of European welfare states and social rights.

If we see half a million deaths across countries from coronavirus — and months of house arrest — then Western societies, economies and politics won’t simply snap back to how they were before 2020 either. Globalisation, US leadership, China’s role, the European Union’s future, the distribution of wealth in societies, and the very social contract between citizens and governments are all now in play. The kaleidoscope has shaken. The world is about to change. 2020 is the defining year of the 21st century. Coronavirus is this century’s July crisis. Welcome back to 1914.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Supporters of democracy within and outside the continent should track these four patterns in the coming year.

Saskia Brechenmacher, Frances Z. Brown

In return for a trade deal and the release of political prisoners, the United States has lifted sanctions on Belarus, breaking the previous Western policy consensus. Should Europeans follow suit, using their leverage to extract concessions from Lukashenko, or continue to isolate a key Kremlin ally?

Thomas de Waal, ed.

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

What should happen when sanctions designed to weaken the Belarusian regime end up enriching and strengthening the Kremlin?

Denis Kishinevsky

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán faces his most serious challenge yet in the April 2026 parliamentary elections. All of Europe should monitor the Fidesz campaign: It will use unprecedented methods of electoral manipulation to secure victory and maintain power.

Zsuzsanna Szelényi