Back in 2019, we started Grand Tamasha on a whim. India’s 2019 general elections were around the corner, and we sensed that there might be a (temporary) market for a podcast focused on Indian politics and policy for diehards hoping to keep up with the campaign action. Nearly five years later, the podcast has become a weekly fixture, and the reception has turned out to be more welcoming than we had imagined.

One of the joys of doing a podcast week in and week out is the ability to read some of the best new books on India and speak with their authors—from journalists to historians, and political scientists to novelists. Last year, we published our first annual list of our favorite books featured on the podcast. As the current year comes to an end and we prepare for a brief podcast hibernation for the holidays, here—in no particular order—are our Grand Tamasha top books of 2023.

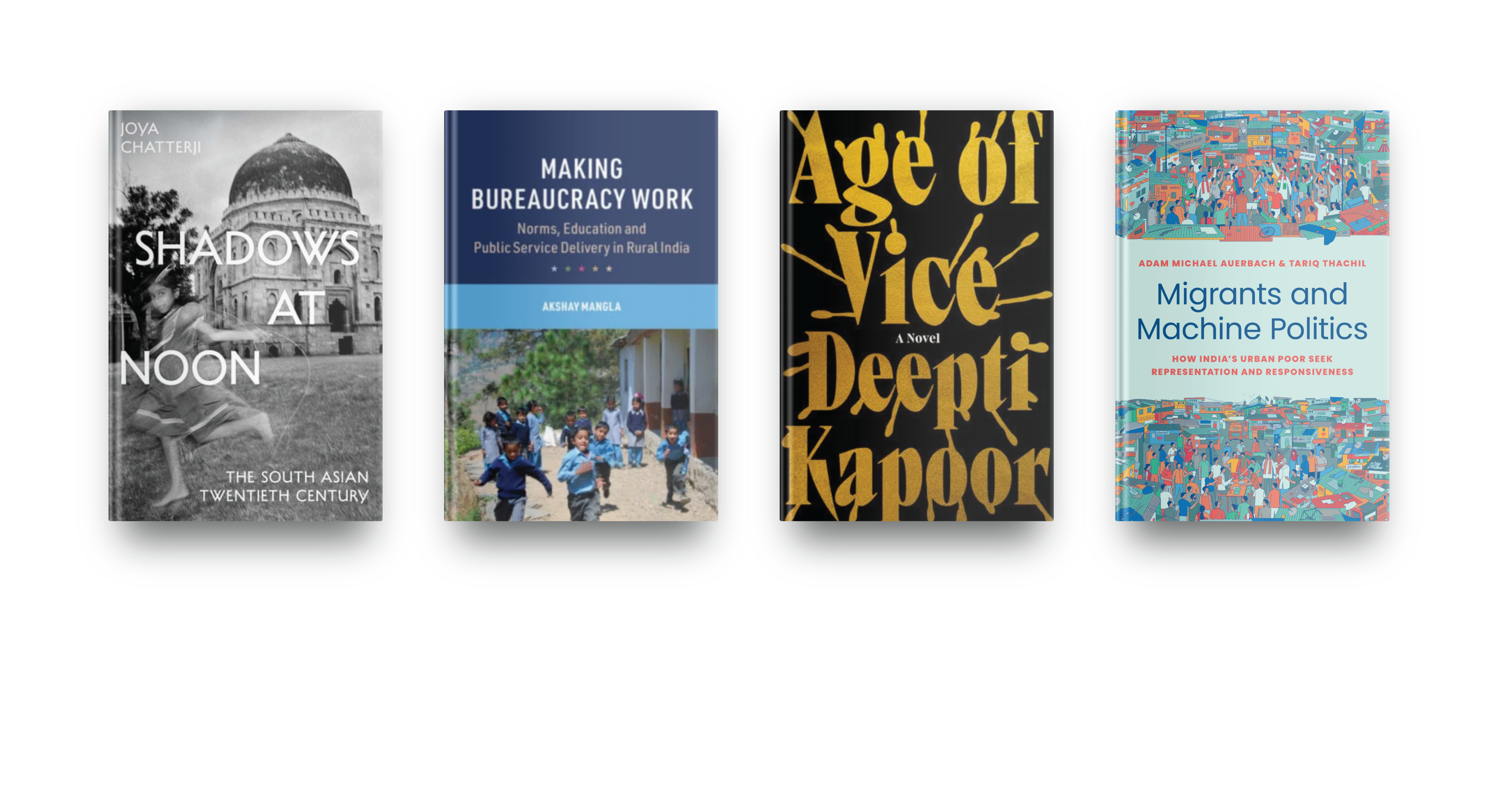

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century

By Joya Chatterji. Published by Yale University Press, Penguin Random House India, Vintage.

This book—clocking in at a breezy 864 pages—is a sweeping look at twentieth-century South Asia. It is a work of history, certainly. But it is equal parts memoir, social commentary, and cultural critique. Its brilliance is that it defies easy classification. Chatterji, a fellow at Trinity College Cambridge and reader in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is the editor-in-chief of Modern Asian Studies, a leading academic journal. In Shadows at Noon, she sums up a career’s worth of scholarship and insights into a book that, as William Dalrymple noted in The Guardian, is destined to become the perfect companion volume to Ramachandra Guha’s acclaimed history of postindependence India, India After Gandhi.

Chatterji tells the subcontinent’s story from the British Raj through independence and partition to the forging of the modern nations of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. While there is plenty of politics and an in-depth discussion of citizenship, nationalism, and political leaders past and present—as one might expect in a definitive work of history—there is equal attention paid to unconventional topics such as food, leisure, and household dynamics. One of Chatterji’s most intriguing literary decisions is to break the fourth wall between the author and the reader, often reverting to first-person narratives while recounting the region’s post-1947 history through her own past, including a compelling account of youthful summers spent at her family compound in West Bengal. If all history was written this well, we would be a society of budding historians.

Migrants and Machine Politics: How India’s Urban Poor Seek Representation and Responsiveness

By Adam Michael Auerbach and Tariq Thachil. Published by Princeton University Press.

Adam Auerbach and Tariq Thachil are two of the best young political scientists working on India in the United States. (Disclosure: I have co-authored papers with both of them.) Their first books, Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums (Auerbach) and Elite Parties, Poor Voters: How Social Services Win Votes in India (Thachil), collected plaudits and scooped up numerous academic prizes. Anyone who has turned on a film or cracked open a book set in modern India knows that Indian slums are regularly portrayed as dens of inequity and deprivation in which citizens are trapped in a vortex of poverty, bad governance, and corruption. Migrants and Machine Politics, based on ten years of fieldwork in the slums of Bhopal and Jaipur, tells us that much of what we think we know is based on myth, not fact. It is as elegant a work of empirical political science you will ever find.

Through detailed ethnography, as well as painstaking data analysis, Auerbach and Thachil show readers that India’s slums—home to tens of millions of residents—are actually intricate, democratic political systems in which patrons, clients, and brokers engage in an everyday contest over representation and responsiveness. One of the book’s most surprising findings is the muted role of identity politics—a factor that has come to define the study of modern India. Because urban settlements are such diverse ecosystems, local leaders cannot rely on caste and religion alone to target voters. Contrary to expectation, it is not ethnicity that bonds citizens to their leaders but rather the latter’s reputation for getting things done. This book will make you question many of your prior conceptions about how urban politics in the Global South actually works.

Age of Vice

By Deepti Kapoor. Published by Riverhead, Juggernaut.

Age of Vice is a love story, wrapped inside a tale of capitalism run amok, wrapped inside a violent story of gangland politics. To call this book a sensation would be the understatement of the year. Critics have celebrated the book, a television series for the U.S. cable network FX is in the works, and Kapoor is hard at work on a trilogy that will follow the Age of Vice characters from the early 2000s to the start of the Narendra Modi era.

In nearly 600 pages, Age of Vice transports readers from the badlands of eastern Uttar Pradesh to the five-star hotels and fabulous bungalows of New Delhi. Its storylines appear ripped from the headlines and melded into a gripping narrative by Kapoor, whose previous life as a beat reporter in India shines through on every page. At the heart of the novel sits the Wadia dynasty—a shadowy business conglomerate run by Bunty Wadia, an industrialist in cahoots with the sitting chief minister of Uttar Pradesh. The book centers on the exploits of Bunty’s son, Sunny, the ne’er-do-well scion struggling to find his place in his family’s vast business empire. Any further detail risks spoiling a plot chock full of twists and turns, leaving readers’ heads spinning as if they were accompanying Sunny on one of his legendary booze- and narcotics-fueled benders. Be forewarned: purchase this book only if you are prepared to ignore your family for the holidays. Once you jump in, you won’t be able to easily escape.

Making Bureaucracy Work: Norms, Education and Public Service Delivery in Rural India

By Akshay Mangla. Published by Cambridge University Press.

Over the decades, India has developed a reputation for having a strong society but a weak state. This bureaucratic, lumbering behemoth has especially struggled to deliver basic public goods like health care, education, water, and sanitation. This book by the University of Oxford political scientist Akshay Mangla teaches us how some Indian states have managed to overcome these endemic weaknesses. In Making Bureaucracy Work, Mangla finds that in some unexpected places, the Indian state has actually succeeded in delivering quality primary education for its poorest citizens despite sharing the exact same institutional framework and often the nearly identical demographic characteristics of poorly performing regions. In Mangla’s telling, this divergence can be traced back to bureaucratic norms. Where bureaucracies are guided by deliberative norms, the state is flexible, adaptive, and responsive to citizens’ needs. But where civil servants rigidly attempt to follow legalistic norms, they may deliver schools on paper but educational outcomes lag behind.

As readers wade through Mangla’s detailed findings, they can feel the blood, sweat, and tears of a researcher who has spent years in the field unearthing the answer to one of the biggest puzzles there is in contemporary India and emerging with a lucid explanation that is both sophisticated and intuitive. This book will be wheeled out by professors for years to come as a demonstration of how intensive fieldwork can inform our understanding of the beast that is “the state.”

Listen to Milan discuss these books on this week’s episode of Grand Tamasha using the player below. Or listen and subscribe through your favorite podcast app.