Lessons from Korea’s political right.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares

{

"authors": [

"Ian Klaus",

"Micah Weinberg"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Democratic Innovation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "CC",

"programs": [

"Carnegie California"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Democracy",

"Domestic Politics"

]

}

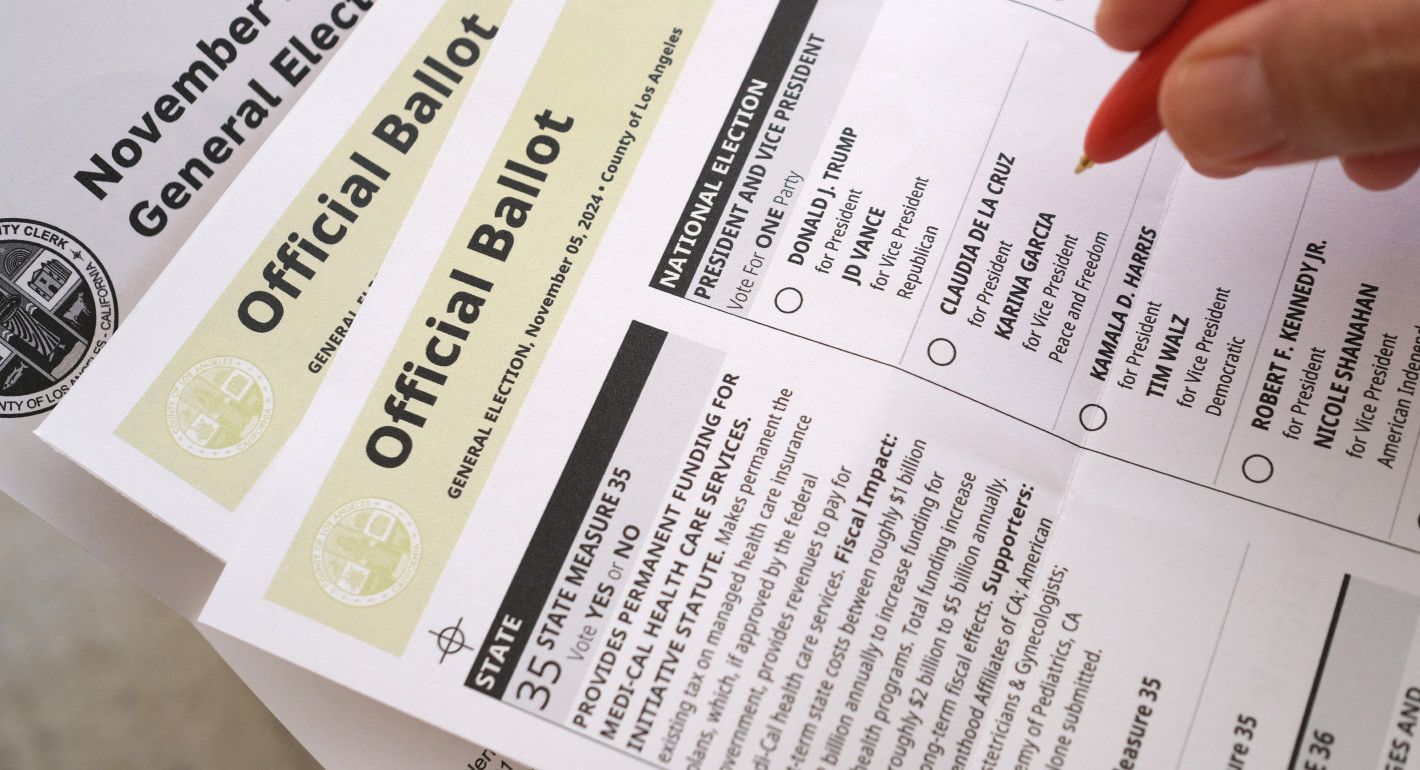

Photo by Chris Delmas/AFP via Getty Images

Increasing the impact of public engagement.

In the wake of seismic shocks from national democratic elections in the United States, it can be easy to overlook the nature and quality of democracy in the American states. This would be a mistake, especially when it comes to California, a subnational unit with outsized influence both nationally and internationally. What one finds in this state, though, is a democracy that is complex, home to both important innovations in public participation as well as some areas of democratic practice that may need reform.

At a baseline level, Californians have long expressed faith in their democratic processes. When asked, in the summer of 2024, whether their ballots would be counted with accuracy in the upcoming election, an overwhelming majority expressed confidence in the tally. And this is in a state that, far from making it more difficult to vote, has dramatically improved the ease of voting, expanded the franchise, implemented nonpartisan redistricting, and experimented with new forms of electoral participation such as the “top two” primary and ranked-choice voting. This enduring assuredness in their state’s processes is paired with the considerable importance Californians place on the concept and values of democracy itself. A majority of Californians, for example, believe the United States should play a leading role in promoting democracy and human rights around the world, according to the 2024 Carnegie Global Affairs Survey.

Yet, amid this confidence and regard, Californians are worried about the future of democracy, a worry that focuses both on Washington, D.C., as well as on aging democratic processes within their state. Across every region, Californians believe the tenor and tone of the national political debate and national partisan polarization are having more negative impacts on state and local government in California. Regarding democracy in their state, survey work by PPIC and Mark Baldassare in 2023 shows that even though Californians are hugely supportive of both the referendum and initiative process, they also believe that these mechanisms are too complicated, are subject to special interest capture, and would benefit from reform.

There often are more than a dozen ballot initiatives in any given election in California. They deal not only with matters of general public concern, such as whether to issue a substantial amount of debt to pay for green infrastructure projects, but also niche issues, such as how the medical treatment of dialysis should be compensated in different healthcare settings—a perennial question in front of voters. These and other economic issues often are brought before the electorate because powerful interests—whether associated with business, labor, or an ideological group—may not have had the outcome that they wanted within the legislature. The sums of money spent on these campaigns are exorbitant, running sometimes into the hundreds of millions of dollars. A tool that initially was designed to be a voice for the people against powerful interests has, in the view of many people, devolved into a tool for the powerful to skirt the decisions of their elected representatives.

California is also a state that, like an increasing number across the United States, does not have meaningful partisan competition at the state level. All 10 constitutional offices and majorities in both houses of the legislature are controlled by Democrats. As such, other channels for public participation have taken on an increased importance. Fortunately, California has been an innovator in these spaces.

California has robust forms of “consultative democracy” in the form of public and stakeholder meetings and a long history of promoting transparency in public decisionmaking, captured in the Brown Act and Bagley-Keene Act. Local governments and state agencies have focused sharply on getting public input into the administration and impact of programs, working with academic experts and community leaders such as those at UC Berkeley’s Possibility Lab and organizations like PolicyLink. These efforts increasingly have sought to incorporate the voices of those who do not have the resources to attend public meetings or who might not be represented by powerful stakeholder interests. Consultation with these communities often is built in as a requirement for programs such as the California Jobs First economic development program or the California Dream for All homeownership program.

California also has been among the leaders in innovating in the field of deliberative democracy. In these types of democratic engagements, a broad and representative cross-section of people are convened to weigh in on a policy issue. The focus, though, is not simply on their preexisting opinions on an issue, but on the act of bringing them together in a community in an information-rich environment to interact with each other and create new ideas from the synthesis of these different perspectives. Perhaps the best-known and most well-established version of these exercises is the Deliberative Polling done by Stanford University, which has been put into practice to tap the wisdom from the interaction of people with diverse perspectives in California, in the United States, and across the world.

One recent example of a deliberative democratic engagement run by Stanford involved organizing publics from California and Texas to deliberate on energy policy within the context of climate change. This exercise—through pre- and post-surveys—showed that this deliberation moved people toward a more comprehensive approach to policy in this area, with Democrats becoming more positive about nuclear power and Republicans more open to a carbon tax. A much more localized example was a “citizens’ assembly” convened in Sonoma County, designed to develop recommendations for the use of the fairgrounds. This was an extensive in-person process but also one that was linked explicitly to a public policy outcome, as the County Board of Supervisors had agreed to be guided by the results of this citizen deliberation.

So, California is at once home to institutions and jurisdictions working at the cutting edge of deliberative democracy and public participation, and yet also to participation processes weakened by complexity and capture. The state must build on the lessons that it has learned from these innovations, and there is a wealth of academic, community, and practitioner expertise that can guide this process. In this effort, California also can learn a great deal from the rest of the world, where direct democracy tools tend to be better integrated with representative democracy, where there are more established traditions of deliberative democracy, and where there are interesting vibrant democratic communities and practices, even at times in countries that are more autocratic at the national level.

Here, California has yet another advantage. Its institutions and even subnational governments maintain strong dialogues with other geographies leading in democratic innovation. These include, most notably, Taiwan’s experience with deliberative democracy. The state also has the ability to access learnings from democratic practices around the globe. When looking at the global scale, it may seem that democracy is in retreat. But in California and throughout much of the world, innovations in democratic practice are legion. These hold the promise of strengthening this system of government as we continue to proceed through this uncertain century.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Lessons from Korea’s political right.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares

European democracy support strategy in 2025 prioritized protecting democratic norms within Europe. This signals the start of a structural recalibration of the EU’s approach to democracy support.

Richard Youngs, ed., Elena Viudes Egea, Zselyke Csaky, …

Despite its reputation as an island of democracy in Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan appears to be on the brink of becoming a personalist autocracy.

Temur Umarov

The Russian army is not currently struggling to recruit new contract soldiers, though the number of people willing to go to war for money is dwindling.

Dmitry Kuznets

It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella