In February 2025, the state of California announced a new deliberative democracy program and platform. Carnegie California played a collaborative role in its development and launch, bringing in scholarly and practitioner expertise from California and around the world. The essay below captures key ideas from the experts who informed that process. To read more on this subject, please go to our California Deliberative Democracy Program essay series page.

Many political observers—be they professional pundits or ordinary citizens who just want their government to be responsive and effective—lament the dysfunction of contemporary U.S. political culture. While political polarization in the United States started rising at least a decade before social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook were launched, that erosion of connection has been exacerbated by social media misinformation and echo chambers that spread manipulative information, encourage hostility toward out-groups, and weaken confidence in the systems that hold society together. Unsurprisingly, public trust in the federal government to do what is right is clocking at historic lows; in 2024, only 22 percent of Americans expressed trust in the government (up from an even lower 16 percent in 2023), according to the Pew Research Center.

On the other hand, much of the public’s sense of polarization in society today is just that—a sense. For example, research from the Hidden Common Ground Initiative shows that Americans largely agree on issues such as healthcare, democracy reform, economic opportunity, and immigration. In fact, humans are wired to connect and collaborate with others. When we share conversations and cooperate toward shared goals, our brains release an array of neurochemicals that reinforce trust and empathy, strengthen relationships, and build group cohesion.

It is well known by anyone involved in organizing civic dialogue that when people engage as individuals to discuss an issue of interest (whether in-person or online), with access to high-quality reference material and the suggestion to be curious and enjoy learning from the group, participants soon come to marvel at how much they have in common with others, recognize their differences as strengths, and soon after that want to start solving problems together. This effect is stunningly predictable. Unfortunately, contemporary society does not prioritize the conditions that produce this effect. For people to have this experience, such conditions must be intentionally produced. Furthermore, if people also want the option of satisfying their enthusiasm for implementing identified remedies, that needs to be actively organized as well.

What Is “Deliberation”?

The term deliberation describes engagements in which people join in robust, well-informed conversation for the purpose of discovering a shared point of view or solution to a problem. A well-designed deliberation also encourages participants to be curious about each other, and ensures participants have enough time in conversation, with breaks in between, for their views to evolve. If a deliberation’s results are meant to become a policy proposal, then participants should be representative of the population that would be expected to support whatever position emerges.

Any person or group can organize a deliberative experience for the purpose of identifying solutions to shared problems, including a body of government, a civic organization, a neighborhood community, and so on. What matters is that organizers are committed to producing the above conditions and trust the process; that they have no thumb on the scale.

Designing Civic Deliberation for Impact

The satisfaction participants derive from well-designed deliberations is often rooted in an expectation that the results of the effort will be acted upon. In the long run, any experience of this kind is only as compelling as its real-world effect. And the odds of delivering on that promise will be better if an intention to deliver tangible results is embedded in the process from the beginning.

Here are some examples of how organizers can think about priming a deliberation for impact:1

Pick a Topic That Resonates With the Public, and Is Clearly Actionable

A good topic for civic deliberation is readily recognized by the community of interest as important in their lives. Second, it is actionable—which also means politically achievable, within a publicly acceptable time frame. The following steps can help achieve these objectives.

- Pressure-test a possible issue in multiple ways to discover potential vulnerabilities related to public perception. This might include organizing community conversations to hear how people talk about a given issue (or simply to see what issues they talk about), paired with some form of opinion polling that taps a representative sample of the population before a final decision is made.

- Prioritize possible topics based on the odds of successful enactment and/or implementation. In addition to resonance, consider political risks and opportunities, impact versus cost, ability to measure impact, and the potential to perceive the change once adopted. Securing change can be more satisfying (and behaviorally reinforcing) when people can see and feel it. Relatedly, start with topics that offer low-hanging fruit; early success will generate momentum for the next challenge, which then can be a higher reach.

- Prioritize state or local opportunities, at least initially. Policy proposals are likely to move through state and local political systems far faster than that of Congress. Additionally, producing the representativeness needed for public legitimacy is more achievable in a city, county or state than nationwide, and having all involved individuals a drive rather than one or more flights away from each other is a material distinction as well. While these features may seem unimportant to some, they make state- or local-level initiatives more affordable to organize, easier to execute, and more likely to produce measurable results sooner. If the goal is impact, this is a good place to start.

Identify Parties Who Will be Pivotal to Securing Change and Engage Them Early

An effective way to strengthen one’s position while also reducing or neutralizing at least some future opposition is to identify key parties in civil society and government early in the process likely to be crucial to the passage or enactment of legislation, the qualification of a ballot measure, or the attitudinal shifts of a community or sector, and seek to involve them in the work early.

- Form a multipartisan advisory council of people with deep local wisdom of the community, including knowledge of political opportunities and risks, who can provide advice throughout the process, either collectively or individually. Even if organizers think their issue is nonpartisan, it can be advantageous in the long run to ensure relationships are built with people across the political spectrum.

- Go to relevant elected leaders and their staff early, listen to what they have to say, and engage with them in ways that can produce a sense of co-ownership. The product of a deliberative process may help reveal popular support for otherwise difficult decisions. Again, approach people associated with both major parties.

- Learn the history and acknowledge the work of those who have been working on the same issues for some time. Seek to identify ways in which a new endeavor might also benefit the goals of existing groups or individuals who have championed the issue of interest in the past, and explore opportunities for collaboration or at least open communication.

Prepare to Stay Relevant Until the Work Is Done (As in, Until New Policy is in Place)

In cases where organizers are external to a local, state, or federal governing body, they should have a comprehensive strategic plan that anticipates the potential need to keep public attention on an issue until a specified goal has been secured (which may be twenty-four months or more). If the formal organizer is a governing body, then supportive stakeholders committed to the expected outcome should prepare in this way.

- Include as part of the final stage of a deliberative process some method of selecting a subset of participants to serve as an implementation advisory group. This participant advisory group bears the responsibility of remaining actively engaged in the months following deliberative decision-making to ensure subsequent steps are consistent with what was originally expressed and expected, while also allowing recommendations to evolve in ways that maintain fidelity with the true desires of the deliberators. The implementation advisers might also participate in, for example, drafting model legislation, informing community outreach strategies, and contributing to and reviewing external messaging.

- Organizers, with input from the participant advisory group, should prioritize ongoing communication with all deliberation participants after the active deliberative process concludes and seek to reinforce the positive impact of their contribution of time and intellect. If participants feel valued and appropriately credited, they are likely to be effective champions for any resulting advocacy or related information campaigns.

- Policymakers who are willing to trust the results of a deliberative process should be publicly acknowledged for their willingness to invite the public to engage as equals on complex issues for the purpose of finding the best remedies for real problems. This is not the norm in contemporary political culture, and it may feel risky. If the public values and supports this approach, it is essential that they make this clear, and reward elected officials willing to lead in this area.

Closing the Loop

Certain people gravitate easily toward this type of participatory civic activity because they have the flexibility to prioritize it, and they like it—it is satisfying. Nonetheless, the ultimate goal is to design a process that can be truly representative, which involves also seeking to minimize logistical—including economic—obstacles that may prevent others from joining, as well as attracting those who are not naturally comfortable with these kinds of experiences but are willing to overcome that discomfort for a sufficiently compelling reason.

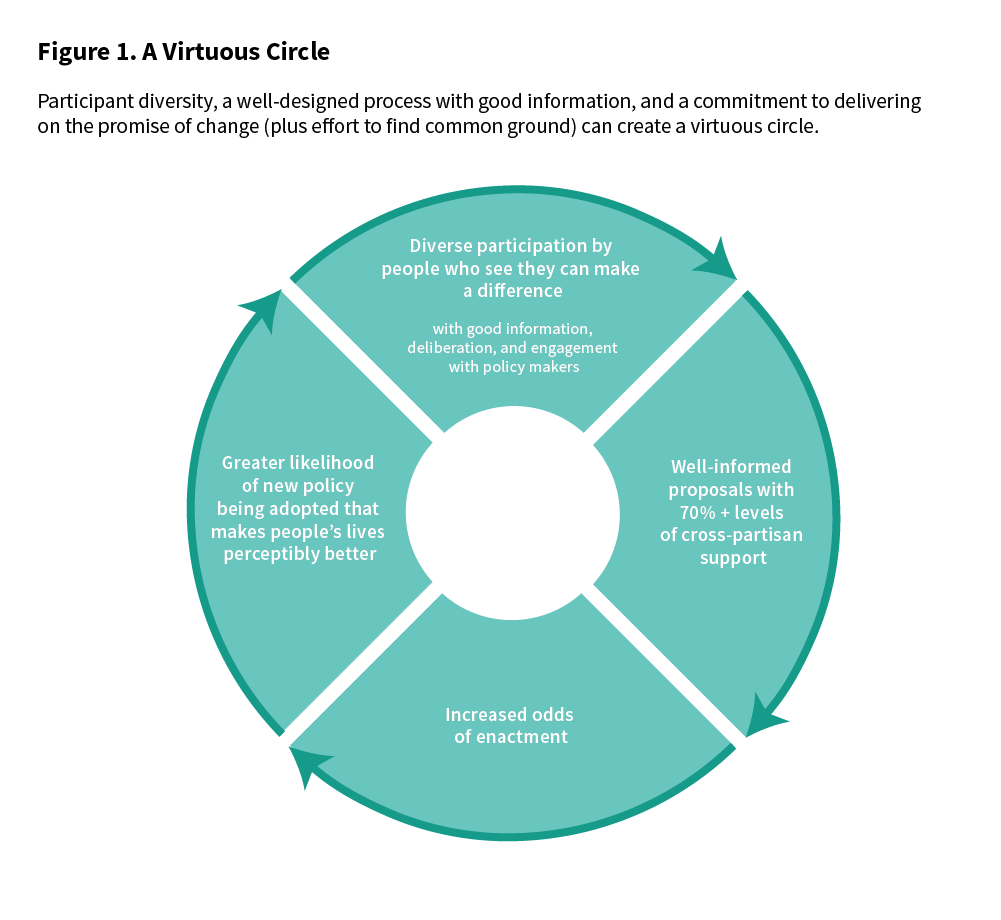

Believing one’s participation truly has the potential to produce a better result for one’s community and possibly beyond, in addition to feeling truly welcome, can inspire people to overcome obstacles and apprehensions—and the inclusion of their experience and insight will add immeasurable value to the quality of the discussions and the validity and credibility of the process overall.

Conclusion: The Proof Is in the Pudding

The United States needs to be producing public policy that better reflects the needs of more people. In particular, the country needs laws that enable Americans nationwide to be productive and creative, participate in their communities, care for their families, and feel free. Well-designed deliberative engagements can help.

There are numerous experiments currently underway in the United States showing what is possible, for example in the state of New Hampshire; Fort Collins, Colorado; and Deschutes, Oregon, to name just a few. Other groups are experimenting with online digital democracy platforms, introducing bridging and “sense-making” algorithms that allow far larger volumes of substantive public comment to be analyzed and quickly shared back with participants, in ways that illuminate common ground that might not otherwise have been visible. Engaged California, Engage Lancaster (in Lancaster City, Pennsylvania), and What Could BG Be (in Bowling Green, Kentucky) exemplify projects in this area.

Today’s work also builds directly on the rich contributions over the past thirty-plus years by organizations such as the Deliberative Democracy Lab and America Speaks (1995–2013), with the American inclination to come together in the face of local challenges to find practical solutions going back much further.

It is true that over the past few decades, increasingly intense attacks on Americans’ shared sense of identity and common purpose have weakened our civic bonds, but perhaps the pendulum is swinging back. Americans increasingly are building forums for inclusive deliberation that recognize our differences as strengths, and their effective deployment as essential to enabling the public to thrive in the coming century. Delivering visible, tangible results can help propel this approach forward—and the more people who bring their unique knowledge, perspectives, insights, and effort to bear on these opportunities, the better for us all.

Notes

1This piece focuses specifically on considerations that can improve impact, with an emphasis on items that might otherwise be overlooked or discounted. It does not intend to comprehensively detail the elements that define effective civic deliberative engagements overall.

.jpg)