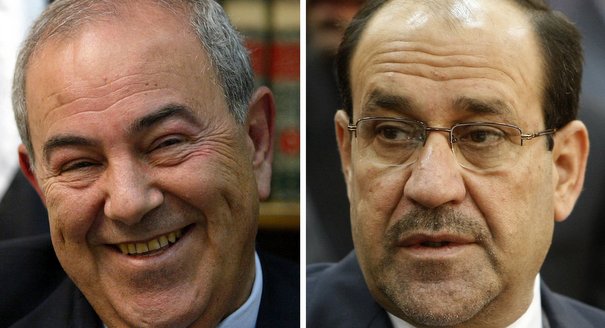

Three weeks after the election, the Iraqi High Election Commission (IHEC) announced the final vote count and the apportionment of seats among the lists. The announcement ends the suspense but opens a period of intense negotiating among parties which could be marred by violence. Iyad Allawi’s Iraqiya list won 91 seats, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law 89 seats, followed by the Iraqi National Alliance (INA) with 70, then the Kurdish alliance with 41.

Election Results

The results are not certified yet, and a major battle is brewing that may postpone the certification for weeks. Dangerously, Maliki and other State of Law members are demanding a total vote recount, rejecting the process established by the election law to settle election disputes. The razor-thin difference in the number of seats gained by Allawi and Maliki will test the commitment to democracy of all Iraqi politicians. It is not certain that they will pass the test. A visibly angry Maliki challenged the results as soon as they were announced, declaring that some of the individuals who won seats should have been banned as Baathists and asking the Justice and Accountability Commission to investigate. He vowed to continue challenging the results and also announced his intention to form a government of national unity. According to a ruling by the head of the Supreme Federal Court, somewhat suspiciously made only the day before election results were released, the task of forming the government will be entrusted either to the leader of the coalition that won the largest number of seats in the elections, or to the leader of the largest coalition formed in the parliament after the elections, whichever is greater.

The razor-thin difference in the number of seats gained by Allawi and Maliki will test the commitment to democracy of all Iraqi politicians.

According to the results announced on March 26, only nine out of the 306 entities competing in the elections won any regular seats (minority seats not taken into account here). In addition to the major lists mentioned above, Tawafuq, an alliance of Sunni parties dominated by the Iraqi Islamist Party, won six seats and the United Iraqi Alliance four. Three additional Kurdish parties also gained representation: Gorran, that broke away from the PUK in 2009, gained eight seats, and two Kurdish Islamist parties, a combined total of six seats. With too few seats to have an impact on their own, the smaller Kurdish parties will most likely side with the Kurdish Alliance in the national negotiations, while continuing to oppose them inside Kurdistan. The INA did somewhat better than expected by gaining 70 seats; about forty of them went to the Sadrist trend, making Moqtada al-Sadr an important player. Also worthy of note is the voting result in the disputed city of Kirkuk, which Kurds want to annex to Kurdistan. Seats there were evenly split between Iraqiya and the Kurdish Alliance. This will likely further complicate the formation of the government, as discussed below.

Recount Stalemate Likely to Continue

The battle over the election results could turn ugly. It might lead to violence, but above all is already leading to calls for abandoning the mechanism for adjudicating controversies contained in the election law. Maliki started calling for a total vote recount as soon as it became apparent that he might not win. Before the elections, it was Iraqiya that had issued dire warnings about the likelihood of election fraud. Allegations of fraud have also come from Tawafuq and the United Iraqi Alliance, particularly by Jawad al-Bolani. The latter has suggested forming a delegation, composed of the president and the heads of all coalitions that won seats in the elections, to confer with IHEC officials to devise a plan to recount at least a specific sample of 10 percent of the ballot boxes. President Talabani has also indicated that he thinks there should be at least a partial vote recount. More moderate voices, including Islamic Supreme Council in Iraq’s leader Ammar al-Hakim, have asked simply for the investigation of irregularities, which indeed the IHEC has been doing. But State of Law representatives reject a role for the IHEC in settling election disputes, arguing that the commission is controlled and manipulated by the United States, which wants Allawi to become prime minister. Anti-Americanism is becoming an increasingly central theme for State of Law representatives.

Maliki has hinted at the possibility of post-election violence, and has reminded the public, without issuing a specific threat or warning—but ominously enough—that he is commander of the armed force.

The IHEC has so far categorically rejected the idea of a manual vote recount and is following instead the legal procedure to look into specific allegations before results are certified. IHEC Chairman Faraj al Haidari has declared that a complete manual vote recount would be highly problematic, increasing the possibility of fraud and taking at least three months to complete.

The issue will not be settled easily. State of Law is determined to obtain a recount, and is turning to scare tactics to have it. Maliki has hinted at the possibility of post-election violence, and has reminded the public, without issuing a specific threat or warning—but ominously enough—that he is commander of the armed force. Demonstrations held in some towns calling for a recount are widely believed to have been engineered by State of Law in a travesty of the Green movement in Iran or of other “color revolutions” organized in various countries to protest allegedly stolen elections. Top officials of the provincial councils in Baghdad and nine predominantly Shia southern regions have also tried to put pressure on the IHEC, stating that unless a recount takes place they will not cooperate with the future government, including refusing to share oil revenue with the central government. Much of this is probably only rhetoric, but the situation could spin out of control.

Neither Maliki nor Allawi can afford to form a government in which Kurds are not represented and neither can afford not to have Sunni support.

The stalemate over the recount is likely to continue for some time, but negotiations over the formation of a government have already started. While rumors abound about deals already struck among various groups, they are highly contradictory. Furthermore, talks between parties continue, showing that no decisions have been reached, although some trends are discernible for second tier actors such as Tawafuq.

Coalition Negotiations Difficult

What gives the negotiations particular intensity is that State of Law and Iraqiya need to win over the same large groups in order to form the government. Neither Maliki nor Allawi can afford to form a government in which Kurds are not represented and neither can afford not to have Sunni support—even if it was numerically feasible, it would be politically untenable. Both also need the support of the INA, or at least of part of the INA. Maliki will have trouble getting some Sunni support—Tawafuq is clearly leaning in Maliki’s direction already, but it only won six seats. Allawi has Sunni support, but he cannot get Kurdish support unless he distances himself from some Sunni allies, including Tariq al-Hashemi and Osama al-Nujeifi, who are advocating a strongly centralized state and have made anti-Kurdish statements. Kurds are determined to exact a high price for their support, including the continuing recognition of Kurdish autonomy, the settlement of the disputes over the boundaries of Kurdistan, closure on the role of the Kurdish military forces, the Pesh Merga, and the holding of the referendum in Kirkuk called for by the constitution. Insistence on the holding the referendum is somewhat surprising at this point, because the vote in Kirkuk was evenly divided between the Kurdish Alliance and Iraqiya.

A test of Maliki’s statemanship is whether he is willing to step aside to ensure that the largely Shia-Kurdish coalition that governed in the past five years will retain control. At present, this appears improbable.

Concerns about Maliki as Prime Minister Complicate Formation

Both sides will have considerable difficulty in forming a viable coalition. Maliki, who has little Sunni support even if he manages to pull Tawafuq into the alliance, needs all the Shia support he can get, so he needs to restore ties with the INA. The problem is that he is no longer the weak compromise candidate that all the Shia groups accepted in 2006. Rather, he has become an assertive leader—with more than a whiff of authoritarianism about him—and has made some real enemies among former supporters. In particular, Moqtada al-Sadr, who lost control of Basra after his militia was defeated there by the Iraqi military acting on Maliki’s orders, is adamant that he will not join State of Law to form a government if Mailki remains prime minister. Others in the INA have expressed similar reservations about Maliki personally. There is no indication so far that the idea of stepping aside is even minimally acceptable to Maliki. As for getting additional Sunni support, Maliki has made it more difficult by defending the last minute ban on some 500 candidates accused of being Baathists. Furthermore, some of his associates as well as INA members like Ahmed Chalabi and Ibrahim Jaafari are now denouncing Iraqiya as a Baathist alliance because of its support among Sunnis. A test of Maliki’s statemanship is whether he is willing to step aside to ensure that the largely Shia-Kurdish coalition that governed in the past five years will retain control. At present, this appears improbable.

Allawi has to walk many fine lines in order to form a successful coalition: first, he must find a way to attract Kurdish support without losing too many of his Sunni allies; he needs to attract at least part of the INA; and finally he needs to live down the contradictory accusations being hurled at him from his adversaries—that he is the protégé of the United States which has manipulated elections in his favor and that he is heading a coalition that will restore Baathism.

The bargaining has only just begun.