It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

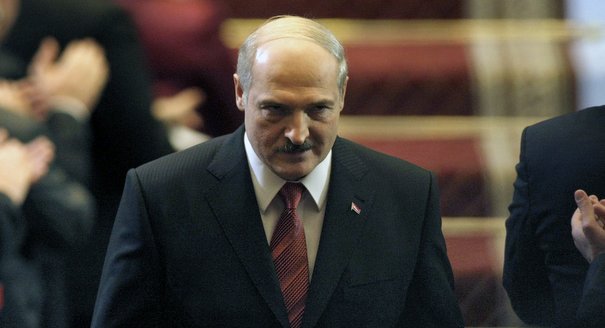

Source: Getty

The West must look ahead to when President Lukashenka is no longer in office and help the people of Belarus develop its civil society.

The brutality and ruthlessness of Alexander Lukashenka’s authoritarian regime in Belarus can sometimes make it seem to be all-powerful. The leader’s recent comments suggesting that he might release political prisoners—because it was not worth the cost to the state to feed and house them—made it clear that he wields his power mercurially, even arbitrarily, with unvarnished contempt for any who oppose or question him. Moreover, the manic nature of Lukashenka’s public pronouncements, his paranoia about internal and external enemies, and the sudden, precipitous rise and fall of prominent figures around him are all classic signs of leadership by cult of personality.

Though the Lukashenka regime is clearly capable of anything in a moral sense, its power is highly circumscribed. The rigidity of the system makes it brittle, and events over the past year have highlighted not only limits on Lukashenka’s personal power, but cracks within his ruling circle and an even deeper instability in the system as a whole. All of this combined suggests that Belarus has reached a turning point, where it is now not only reasonable but essential to think about a post-Lukashenka future.

In the past six months, the Belarusian economy has collapsed. The government has run entirely out of IMF bailout funds, and has requested more, which will come slowly, if at all. Thanks to the government’s merciless crackdown on the opposition after December’s fraudulent presidential contest, Western financial assistance seems entirely barred, and Russia is hardly a better option. Moscow is prepared to offer Lukashenka a few billion dollars’ worth of credit, but only in exchange for transferring the crown jewels of state industry to private Russian ownership. After endorsing a new anti-crisis loan agreement between Belarus and the Russian-dominated Eurasian Development Bank to provide $3 billion over three years, Russian Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin insisted the deal was conditional on privatization of Belarusian state assets worth “no less than 2.5 billion dollars annually.”

The situation of average Belarusians has never been worse in recent memory. With the currency plummeting to nearly half its value just six months ago, citizens are scrambling to exchange their depleted cash savings for foreign hard currency and durable goods, neither of which is readily available any longer, except at exorbitant black market prices. For the millions of Belarusians who rely entirely on government pensions, welfare payments, or wages from jobs in state industry, this is already a life-changing disaster.

Meanwhile, the nation as a whole cannot help but feel more vulnerable than ever before, as it has endured growing isolation from East and West brought on by the regime’s irresponsible actions, and then suffered a gruesome terror attack on the Minsk subway still vividly imprinted on popular memory, despite the government’s suspiciously quick apprehension and prosecution of the alleged bomber.

These dire straits cry out for a concerted policy response from those in the West concerned for the future welfare of Belarus and its people. At the same time, the prospect of Lukashenka’s departure, however imminent or likely, appears to be the only game-changing scenario available in the short term, leaving many people tempted to propose options for accelerating that outcome. But enhancing already intense external pressure on the state is not the answer, as it could too easily provoke even more backlash and hostage-taking, while further sanctions against Belarusian businesses or constraints on trade would certainly rob ordinary citizens of their few remaining reliable sources of income, and enable Lukashenka to cast the West as the real cause of Belarusians’ suffering.

It should be obvious by now that the real challenge for outsiders and Belarusians alike is to think about what comes after Lukashenka. In the West, answers to this question too quickly devolve into a guessing game about who might take his place—whether someone from the current elite or the opposition—which merely feeds Lukashenka’s own paranoia about a Western or Russian-backed coup, while compromising any individual leader anointed by the West. This is also the wrong track because it perpetuates a kind of thinking about political life in Belarus defined by Lukashenka himself.

If the core requirement for securing Belarus’ democratic future were to unite the opposition around a single, charismatic leader, there is no doubt it would have happened already—there have been more than enough candidates willing to risk everything for the opportunity. In reality, even a united opposition, if given the chance to govern, would still lack a comprehensive program to manage the country’s perilous condition, and could not draw on sufficient human resources and national political will to reform the country’s nearly gutted institutions.

Preparing for the day after Lukashenka must be primarily about the Belarusian people as a whole, not about Lukashenka, the West, or the opposition. If they want a different system, not just a different figurehead, they must be prepared to imagine it and to work for it. That is why Western governments that want to help Belarus should think in terms of enhancing the skills and capacities of Belarusian civil society—not just for Belarusians in exile, or for those in Minsk, but for everyone throughout the country. Above all, Belarusians need tools to pierce the veil of disinformation woven by the regime, and for that they need access to information from independent domestic and international sources.

Belarusians are no less creative or talented than citizens of any other country, but they have been denied the ability to organize effectively to petition for changes in political, social, or economic spheres, or simply to change things on their own through good ideas and hard work. That is why Westerners should sponsor programs that teach the basic skills of community organization, advocacy, and entrepreneurship, without imposing political or ideological content. The best way to transmit these skills is, of course, for Belarusians to experience them in practice; this can be achieved by easing the requirements for Belarusians to travel in the West—not only in the border areas of neighboring states like Poland and Lithuania, but throughout the European Union and even to the United States. Those in the West who readily call on Belarusians to put themselves in harm’s way by opposing a violent regime should be equally prepared to open their own borders, societies, and economies to Belarusians without requiring them to overcome a multitude of bureaucratic hurdles or pay inordinate fees.

We can no longer allow Lukashenka to define both the problem and the solution for Belarus. Although he can—and must—be held responsible for what he has done to the country and its people, the future is not about him. Yet considering current Western policies, we are likely to have a rude awakening when Lukashenka eventually goes and we find ourselves sitting on a library of papers and a budget full of programs, none of which deal adequately with the real and urgent problems of ordinary Belarusians—problems that have enabled Lukashenka to hold onto power for seventeen years. We have been behind the curve on Belarus for long enough. Now it is time to think one step ahead.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

Europe’s policy of subservience to the Trump administration has failed. For Washington to take the EU seriously, its leaders now need to combine engagement with robust pushback.

Stefan Lehne

Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

Having failed to build a team that he can fully trust or establish strong state institutions, Mirziyoyev has become reliant on his family.

Galiya Ibragimova