Within a few years, it will be two decades since the United States and India signed their epochal agreement on civil nuclear cooperation. When finalized on July 18, 2005, this controversial accord evoked deep fears that the international nonproliferation regime would be irrevocably gutted because Washington proposed to resuscitate nuclear trade with New Delhi despite the latter’s refusal to forego possession of its nuclear weapons—a privilege not extended to any other non-signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). With the passage of time, however, it has become clear that the global nonproliferation regime has survived the U.S.-India agreement, while the bilateral relationship has been dramatically transformed across myriad dimensions, especially in regard to diplomatic engagement, defense cooperation, and high-technology collaboration.

Despite these remarkable gains, the full potential and promise of the 2005 nuclear agreement—and the larger U.S.-India partnership—has yet to be realized on at least two counts. Where India is concerned, New Delhi is long overdue in removing the obstacles that prevent its purchase of nuclear reactors from the United States, consistent with the written commitments it made during the implementation of the nuclear deal. Where the United States is concerned, a different challenge persists that is no less urgent: matching policy with vision. Given President Joe Biden’s commitment to strengthening India’s power in the ongoing competition with China, Washington’s desire to treat New Delhi’s nuclear weapons program as unique—the fundamental premise that underlay the 2005 accord—must now be consciously fructified in ways that affect his administration’s decisionmaking on how to build a more ambitious partnership with India.

In India, a Liability Law Constrains Civil Nuclear Cooperation

While the U.S.-India civil nuclear agreement was broadly driven by the intention of revamping the previously troubled U.S. relationship with India, it concretely expressed U.S. president George W. Bush’s strong desire to change the way that the United States would relate to India on nuclear issues. Both Bush and his Indian counterpart, prime minister Manmohan Singh, envisaged the agreement as creating opportunities for the U.S. nuclear industry to return to India in a significant way and thereby contribute to accelerating India’s economic growth by expanding its baseload energy supply from low-carbon sources.

In the aftermath of the agreement’s conclusion, the Singh government consciously set out to make both international and domestic private sector participation in India’s nuclear power program possible. Toward that end, it sought to enact nuclear liability legislation that was consistent with international standards. These standards, as codified in the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC), require that all burdens imposed by any nuclear accident be channeled solely to nuclear plant operators, rather than to suppliers, to ensure swift compensation in the event of any mishap.

For a while, the Singh government’s efforts appeared to be on course: it introduced legislation on nuclear liability in India’s Parliament that closely tracked with the standards of the CSC. But fate conspired against success. By an accident of the calendar, the Indian Supreme Court issued a decision in 2010—when Parliament was debating the nuclear liability legislation—that confirmed an earlier settlement pertaining to the deadly 1984 gas leak disaster at Union Carbide Corporation’s chemical plant in Bhopal. The court’s judgment suddenly reminded the Indian body politic of that ghastly accident, which caused thousands of deaths and many tens of thousands of injuries some twenty-five years earlier.

As a result, immunizing nuclear suppliers, as Singh’s proposed legislation intended to do consistent with international norms, suddenly became extremely hard. The prime minister’s lack of an absolute majority in Parliament and the strident hostility of the opposition, especially the Bharatiya Janata Party, to his civil nuclear agreement unfortunately combined to produce a convoluted law that accepted the nuclear plant operator’s liability in principle while simultaneously bestowing on it the right to seek legal recourse against its suppliers for defective products or technology.

India’s nuclear liability law—the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA)—thus made the country an outlier in the realm of international nuclear commerce, and the CLNDA complicated foreign efforts to supply the advanced nuclear reactors that the Singh government had once envisaged would be the early fruits of its civil nuclear agreement with the United States. The Indian government attempted to create work-arounds to resolve the problems created by its law. These have included providing governmental clarifications to the textual ambiguities, defining the limits of a supplier’s liability in specific financial terms, and committing to create an insurance pool to limit the supplier’s risks in case of an accident.

Thus far, however, these solutions, individually or collectively, do not seem to have sufficiently assuaged all suppliers’ anxieties about the infirmities of the CLDNA. Although foreign state or parastatal suppliers may be able to better manage these legal problems—because sovereign entities can accept risks that private actors invariably cannot—most private companies are unlikely to enthusiastically embrace the Indian nuclear market until a solution to the conundrum of supplier liability is found.

For a long time, this issue did not seem particularly significant, as both the U.S. and Indian governments moved away from civil nuclear trade to focus on expanding other areas of their bilateral relationship. Since the costs of nuclear power are also high, the Indian government focused its attention on other non-fossil energy sources, such as solar and wind, which have enjoyed considerable success more recently. But the challenge of providing sufficient and stable baseload power in India remains, and nuclear energy is still an attractive solution at a time when the country remains determined to reduce its carbon emissions to mitigate climate change without sacrificing economic growth.

That many Indian coal-fired power plants—among its most important sources of baseload power and which at present constitute more than 50 percent of India’s power mix—will face retirement at some point during this decade or early in the next only makes their replacement by newer nuclear technologies, such as small modular reactors (SMRs), potentially attractive. It is not surprising, then, that energy security, climate adaptation, and geopolitical interests have all combined in New Delhi’s calculus to keep the nuclear power option alive, despite the high capital costs of nuclear power plants.

Consequently, India has continued its investments in nuclear power through the import of reactors from Rosatom, the Russian state corporation that seems undeterred by problems of liability in India because of the protections offered by the government in Moscow. New Delhi is also engaged in ongoing negotiations with Paris for the construction of six new large European Pressurized Reactors at Jaitapur, but this deal is yet to be concluded because the French supplier, Électricité de France, confronts unresolved problems, including on liability. Finally, India has pursued an intermittent and long-running but largely desultory conversation with the United States—in particular with the Westinghouse Electric Corporation corporation—for the construction of six AP1000 reactors in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh.

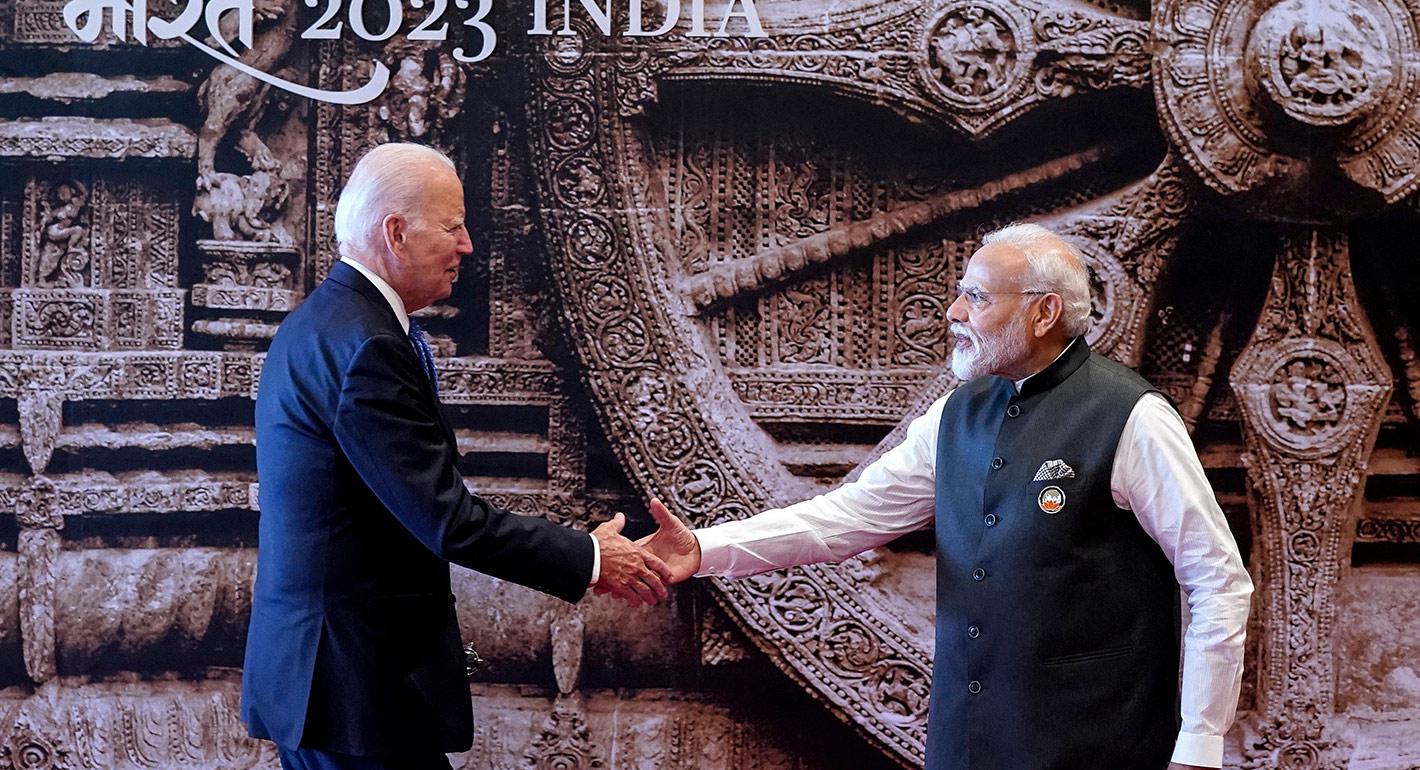

This last initiative has unexpectedly received new impetus during the Biden administration. Because of Biden’s crucial role while he was in the U.S. Senate in bringing the U.S.-India civil nuclear agreement to completion, he has now as president championed the idea of tangibly consummating this accord by completing the negotiations for U.S. nuclear reactor sales to India. Reflecting this interest, and the renewed discussions between the U.S. and Indian governments behind the scenes, the joint statement issued after Biden’s September 2023 visit with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in India declared that the two leaders “welcomed intensified consultations between the relevant entities on both sides to expand opportunities for facilitating India-U.S. collaboration in nuclear energy, including in development of next generation small modular reactor technologies in a collaborative mode.”

Realizing this promise, however, will require solutions that have eluded the two sides thus far. Westinghouse, the supplier of high output nuclear power plants, remains skittish about sales to India with the absence of durable assurance of limited liability in the event of an accident. At least one other American company, Holtec International, which supplies SMRs, already operates a components factory in India and is eager to explore SMR sales in the country and across West Asia, but these discussions are still in the early stages.

Potential Solutions to New Delhi’s Predicament

Given the Biden administration’s interest in consummating the civil nuclear agreement, as well as India’s interest in expanding foreign participation in its nuclear energy program, it is past time for the Modi government to rectify the nuclear liability problems that it has inherited—ironically due to the obstructiveness of Modi’s own party, albeit long before he led it. The cleanest solution to the current predicament would be to amend India’s CLNDA to bring it in line with the international CSC by channeling all liability in case of a nuclear accident solely to the operator of a nuclear plant, with the operator in turn protecting its interests by relying on an insurance pool for financial safety. (India has already moved to create such an insurance pool pursuant to the CLNDA, but it has not been fully funded yet.)

A clear and transparent amendment of the CLNDA would not only restore the confidence of foreign and domestic nuclear suppliers in regard to their absolution from liability, it would also remove uncertainties that have arisen from the Indian government’s attempts to clarify the ambiguities in the law through its 2011 Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Rules, as well as more unconventional documents, such as the “Frequently Asked Questions and Answers on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act 2010 and related issues” issued by India’s Ministry of External Affairs in 2015.

These texts are undoubtedly intended to reassure suppliers that the CLNDA does not burden them with excessive liability in case of any accident. But by their nature, they cannot provide any foolproof assurances—precisely the kind that private suppliers of any importance would desire—because the extent and the locus of liability in the event of a catastrophe would be determined not by the Indian government but by the nation’s courts. Precisely because the issue of liability will ultimately be determined by the judiciary and not the executive, it is important that India’s governing legislation be clearly consistent with international norms as reflected by the CSC if the country is to benefit from international trade in nuclear technology.

Unfortunately, no decisive rectification of the problems in India’s CLNDA is possible before the next general election in 2024. Not even a popular prime minister such as Modi is likely to take a bite of this controversial apple before he has secured another term in office and, even then, only if he enjoys a decisive majority that enables him to easily amend the law despite opposition. Whether the next election will produce such an outcome cannot be predicted.

Two other fallback strategies deserve consideration in the interim. The Indian government should consider memorializing the liability ceilings derived from the law and elaborated upon in the “Frequently Asked Questions and Answers. . .” document into the commercial contracts negotiated with relevant nuclear suppliers. Such a solution would not correct the CLNDA’s inconsistency with the CSC, but it could go some distance in assuaging suppliers’ fears about exorbitant and potentially open-ended liability, which could arise either from ambiguities in the CLNDA or its intersection with different rights enjoyed by potential plaintiffs in other domains.

Despite the mitigating benefits of this solution, the Indian government and its nuclear subsidiaries have been reluctant to incorporate these ceilings into their commercial contracts with foreign suppliers. The ostensible justification for this reluctance is redundancy: since the CLNDA already indicates the limits of liability, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India avers that reiterating these numerical ceilings in any business contracts is unnecessary. This contention, however, accentuates the very suspicions that are meant to be allayed.

Since the complications caused by the CLNDA can only be redressed for now through additional reassurance, citing redundancy as a reason to avoid providing such comfort is only self-defeating. The record of the U.S.-India civil nuclear negotiations only provides further justification for such a solution. After all, the United States went out of its way to provide reassurances on many aspects of the nuclear deal even when they were legally unnecessary simply to convince the Indian government of its good intentions. There are no good reasons for India to do any less today.

The final, and perhaps least satisfying, fallback solution is an intergovernmental understanding that confirms the limited liability of participating foreign private companies involved in nuclear trade with India. In principle, an assurance conveyed by the Indian government to the U.S. government and its principal international partners as appropriate about the limits of liability would provide the encouragement that enables friendly states to encourage participation by their national businesses in India’s nuclear program.

Obviously, such a solution constitutes only a confidence-building measure and not a legal guarantee of limited immunity as far as any of the foreign suppliers are concerned. Yet, it may be helpful to nudge the latter if their governments can vouch for India’s good faith before the complicated negotiations over nuclear technology procurements are completed. For reasons that are hard to understand, the Modi government has not pursued such an inexpensive solution despite professing interest in bringing the civil nuclear agreement to a happy commercial conclusion.

India, undoubtedly, has vastly benefited from the civil nuclear agreement with the United States since its announcement in 2005. To this day, New Delhi has on the basis of that compact sought continued benefits in terms of more liberal licensing of controlled commodities, the further removal of Indian establishments from the U.S. entity list, and the procurement of advanced technologies and weapons from the United States.

Successive administrations in Washington since president Geoge W. Bush have been highly supportive of these requests, but it is a pity that India has not moved far or fast to make good on the formal commitment that its own government made to the United States in 2008 in regard to fulfilling its obligations to purchase U.S. nuclear reactors. Modi should now consider addressing this issue expeditiously so as to sustain the transformation of the U.S.-India relationship initiated by his predecessors and that he himself has heavily invested in.

In the United States, India’s Nuclear Weapons Still Get in the Way

Even as India looks for ways to realize the commercial promise of the civil nuclear agreement—an objective that the Biden administration must be congratulated for making its own—the administration still has another bigger and more consequential task arising out of this accord: addressing the issue of India’s nuclear weapons program in U.S. grand strategy.

The underlying premise of the civil nuclear agreement was that India’s nuclear weapons did not threaten U.S. geopolitical interests and, as such, should not be treated as an impediment to resuscitating civilian nuclear trade with India or deepening cooperation with New Delhi in order to preserve the balance of power that favors freedom in Asia. This conviction drove the dramatic shift in Bush’s policy toward India long before China was perceived to be the United States’ most consequential competitor in the global arena.

Today, when it is amply clear that assertive Chinese power constitutes the most pressing strategic threat in the Indo-Pacific, maintaining a favorable geopolitical equilibrium in Asia has become all the more important to the United States. In an ideal world, the burgeoning U.S.-India relationship would permit New Delhi to join hands with Washington in dealing with its most dangerous contingencies, to include the ever more challenging problems arising from Chinese threats to U.S. treaty allies in Asia or a possible war over Taiwan.

However likely or unlikely Indian contributions might be in such eventualities—and Americans and Indians have differing views on this issue—it is easy for strategists in Washington and New Delhi to agree that U.S. interests are best served by the existence of strong power centers on China’s periphery. Such a geopolitical configuration can help to constrain Beijing’s capacity to misuse its power as long as the countries involved are capable, minimally coordinated among themselves militarily, and above all, deeply intertwined with the United States.

Being U.S. allies, Australia and Japan already meet these criteria, but India does not. Consequently, India’s value to the United States—in the context of the ongoing U.S.-China rivalry—derives principally from New Delhi’s ability to stand up to Beijing independently. If India possesses such a capacity, it will limit China’s ability to throw its weight around in Asia without New Delhi having to rely persistently on Washington’s assistance in effectively balancing Beijing.

Ever since the Bush administration declared its ambition “to help India become a major world power in the 21st century,” successive dispensations in Washington have doubled down on building Indian capabilities despite the dilemmas New Delhi often poses to U.S. interests, motivated precisely by the aim of enabling India to accumulate sufficient power so as to permit it to checkmate China independently when required—a capacity that advances U.S. interests both in Asia and globally.

The ultimate bedrock of India’s ability to constrain Chinese assertiveness derives from its nuclear weapons because these instruments still remain the most effective tools against the worst depredations that China can inflict on India. Given this fact, U.S. policy since the Bush administration—departing from some thirty years of nonproliferation orthodoxy—has consisted of leaving India’s nuclear weapons program alone. As long as its devices were both safe and secure, the United States turned a Nelson’s eye toward New Delhi’s nuclear weapons because, if these capabilities helped protect India from Chinese threats, they advanced Washington’s objective of nurturing an Asian multipolarity that limited any pernicious exercise of Chinese power.

As China continues to rise, its assertiveness persists unabated, and its nuclear arsenal expands with no end in sight, there is even more reason to “regard Indian nuclear weapons as an asset in maintaining the current balance of power in Asia.” Because of the conspicuous weaknesses in India’s nuclear capabilities vis-à-vis China, there is a compelling reason, at least by the canon of realist geopolitics, for Washington and its friends to aid New Delhi in increasing the effectiveness of its nuclear deterrent. The constraints imposed by the NPT upon the United States and other treaty signatories, however, prevent such assistance from being extended to India in any direct way.

But the obligation of not assisting the Indian nuclear weapons program does not mean that the United States should persist with its current policy of preventing India from improving its own strategic capabilities. The current thicket of U.S. export controls and end-user verifications are premised on the notion that any technology that has even tenuous connections to the Indian nuclear weapons program and its delivery systems—both of which are conceived of in highly expansive terms to include penumbral elements such as advanced computing, X-ray equipment, commercial space launch components, exotic materials, and nanotechnology—are to be denied to India.

As a result, many Indian efforts to acquire technologies that do not directly support its nuclear weapons program are nonetheless routinely denied export licenses, and the linkages that ought to be nurtured with India’s strategic enclaves—in support of both Indian and U.S. interests—are stymied. The Biden administration, to its credit, has implemented praiseworthy policy decisions to streamline licensing red tape, including through the recently launched Strategic Trade Dialogue. But even these actions cannot assuage the bitterness still felt by many in the Indian strategic establishment who are convinced that the United States talks a big game when it comes to supporting India’s international emergence but falls short when its continuing licensing practices fail to live up to its soaring rhetoric.

That a pervasive U.S. policy of technology denial on account of India’s possession of nuclear weapons persists close to two decades after the conclusion of the civil nuclear agreement is absurd. Washington’s obligations to the NPT do not require such a maniacal control regime as far as India is concerned, which in any case does not reflect the contemporary logic of the U.S.-India strategic partnership. The inherited nonproliferation rules and how they are implemented not only prevent India from incurring the full benefits deriving from the underlying premise of the original civil nuclear agreement but, even more importantly, subvert the overarching objective that drove its negotiation: assisting India’s ascendancy to create the Asian multipolarity that balances China’s rise. On this count, both the administration and the U.S. Congress are of one mind. Consequently, it is now time for the executive branch to bring its application of the nonproliferation rules in accord with its core strategic goal of building Indian capabilities to effectively resist expanding Chinese power.

Finding a Way Forward

Because the Biden administration has faithfully made this objective entirely its own and has accordingly intensified cooperation with India, it can no longer avoid addressing the issue posed by the existence of New Delhi’s nuclear weapons. This is all the more urgent because many of the projects undertaken by the administration, including the U.S.-India initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET), contain areas such as space technology, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence where cooperation with India will be constrained (or will be unable to reach its full potential) because long-standing policies within the executive branch will prevent the United States from collaborating in cutting-edge activities with India and its most important strategic constituencies.

Either way, these constraints will not only limit India’s accumulation of power, but they will also strengthen the strong residual conviction among India’s national security managers that for all the advances of the last two decades the United States—in contrast to Russia—is still not a trustworthy partner where strategic cooperation of importance to India is concerned. This implies that Biden’s ambition to finally fructify the 2005 civil nuclear agreement cannot end with the sale of U.S. nuclear reactors to India. Rather, it must extend to revising long-standing U.S. policies that continue to make the existence of India’s nuclear weapons program an insuperable obstacle to deepened technological cooperation.

Consequently, only when Biden and Modi resolve the last outstanding issues arising from the momentous civil nuclear cooperation agreement—removing the impediments posed by India’s nuclear weapons and reforming India’s nuclear liability law respectively—will the United States and India fully realize the promise of that accord reached in Washington many summers ago.