In this moment of geopolitical fluidity, Türkiye and Iraq have been drawn to each other. Economic and security agreements can help solidify the relationship.

Derya Göçer, Meliha Altunışık

Source: Getty

South Korea’s economic growth will almost certainly slow over the coming decades—but writing off the country’s potential would be a mistake.

The so-called Miracle on the Han River is a well-known rags-to-riches story that would make Horatio Alger proud. In five decades, South Korea rose from being one of Asia’s poorest countries to become one of the region’s richest and most advanced economies. South Korean firms like Samsung and SK Hynix make a wide array of electronic products, including some of the world’s most advanced semiconductors. Hyundai Motors is a world-renowned automobile manufacturer, and South Korea is also a major shipbuilder.1 And most recently, the explosion of K-pop and K-culture has raised the country’s soft power brand as never before.

South Korea has been able to do all this while facing one of the world’s most dangerous geopolitical and geoeconomic landscapes: neighboring North Korea with its growing number of nuclear warheads and other weapons of mass destruction (WMD), China’s increasingly robust and aggressive military power-projection capabilities, a newly formed Russian–North Korean defense pact, the worsening U.S.-China technology wars, and the highly uncertain state of global supply chains.

Moreover, throughout the 2020s and beyond, anemic economic growth will be the norm rather than the exception, due in no small part to South Korea’s rapidly aging population and low birth rate. According to a long-term projection made by the Korea Development Institute (KDI)—South Korea’s premier economic think tank—the “baseline” prediction for the country’s average economic growth rate between 2023 and 2030 is 1.9 percent, dropping to 1.3 percent between 2031 and 2040, and then to 0.7 percent from 2041 to 2050. Compared to the country’s frequent double-digit growth rates from the mid-1960s until the late 1980s, South Korea’s economic growth looks increasingly like Japan’s weak growth in recent decades.2 The authors of this November 2022 long-term economic growth report by KDI noted that longer-term growth projections have three trend lines: pessimistic, baseline (cited above), and optimistic. From 2041 to 2050, for example, the worst-case scenario is an annual average growth rate of 0.2 percent, while the best-case forecast is 1.1 percent.

South Korea’s domestic political future is also uncertain. Political divisions between the right and the left remain deep and unrelenting. The country’s April 10, 2024, National Assembly election was a major defeat for the ruling People Power Party (PPP) and a clear-cut victory for the main opposition, the Democratic Party (DP). Although it is beyond the scope of this study to delve into critical dimensions of South Korean politics, the DP earned 175 National Assembly seats out of 300, while the PPP only got 108 seats.3 The rest of the seats were divided among minor opposition parties and independents. The outcome was a major setback for President Yoon Suk Yeol with three years remaining in his five-year term, which will end in May 2027.

For the next three years, the DP and its de facto coalition partners in the opposition are going to use a legislative supermajority to pass their own bills that are likely to run counter to Yoon’s agenda. Gridlock is going to be the new normal, since Yoon is going to veto bills that conflict with his administration’s beliefs, cost concerns, and stance on populism. In turn, the DP will do everything possible to stymie Yoon’s presidential agenda in hopes of bolstering its own chances of winning the country’s next presidential election in March 2027. How much the Yoon administration is willing to cooperate with the DP remains uncertain, but if South Korea wants to be at the forefront of economic and technological innovation in this age of artificial intelligence (AI), a new political consensus must emerge to spur new growth with more business-friendly policies. But even though the DP argues that it also supports AI-driven innovation, its call for higher corporate taxes, its pro-labor stances, its antinuclear energy platform, and its opposition to the abolishment of South Korea’s extremely high capital gains tax all point to greater regulations and other policies that are unfriendly toward South Korea’s large businesses.4

Can South Korea reinvent itself as it did starting in the late 1960s with its then unprecedented economic transformation? Will Seoul overcome immense structural shifts and threats and emerge as a major AI hub? Many doubt that South Korea can continue to be a significant middle power with major military and technological capabilities. The magnitude of the threats and challenges confronting the country is formidable.

But at the same time, writing off Seoul as a has-been powerhouse in the areas of exports and technology is likely to be a losing proposition. Despite all the odds stacked against South Korea, the country could reach a new phase in its transformation if it becomes a laboratory for the AI revolution. To do so, South Korea must maximize its strengths as a global exporting power with a highly educated workforce, capitalize on smart investments in cutting-edge technologies to move up the value chain, deftly balance its alliance with the United States while navigating severe security challenges posed by North Korea and China, and continue to leverage the attractiveness of South Korean soft power and cultural exports. And while it’s impossible to accurately forecast future scenarios in North Korea, the possibility of regime or state collapse in the country cannot be ruled out. Even though North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un’s grip on power seems to be as strong as ever since he ascended to power in December 2011, most of North Korea’s threats are domestic rather than external.

Finally, although the mantra of expanding economic growth was a key facet of post-1945 global development, there are mounting counterarguments to the doctrine of continuing growth based on accelerating environmental effects (including climate change) and socioeconomic inequalities. As proponents of so-called degrowth such as economic anthropologist Jason Hickel say, “degrowth is about reducing the material and energy throughput of the economy to bring it back into balance with the living world, while distributing income and resources more fairly, liberating people from needless work, and investing in the public goods that people need to thrive.”5 Even if degrowth is highly unlikely to be adopted as official doctrine by future governments, given that South Korea functions as a thriving market economy, much lower growth rates will affect virtually every aspect of life in the country.

South Korea is well aware of these challenges, and it should seriously consider several policy proposals to reinvent itself in an era characterized by much lower growth rates. Some of the key steps South Korea should take during the rest of the 2020s include:

The story of South Korea’s economic takeoff starting in the late 1960s and its emergence as a major manufacturing powerhouse is well known. This successful trajectory has been referred to as the Miracle on the Han River, catapulting South Korea from being one of Asia’s most impoverished countries in the 1950s after the Korean War to becoming Asia’s fourth-largest economy in the twenty-first century.

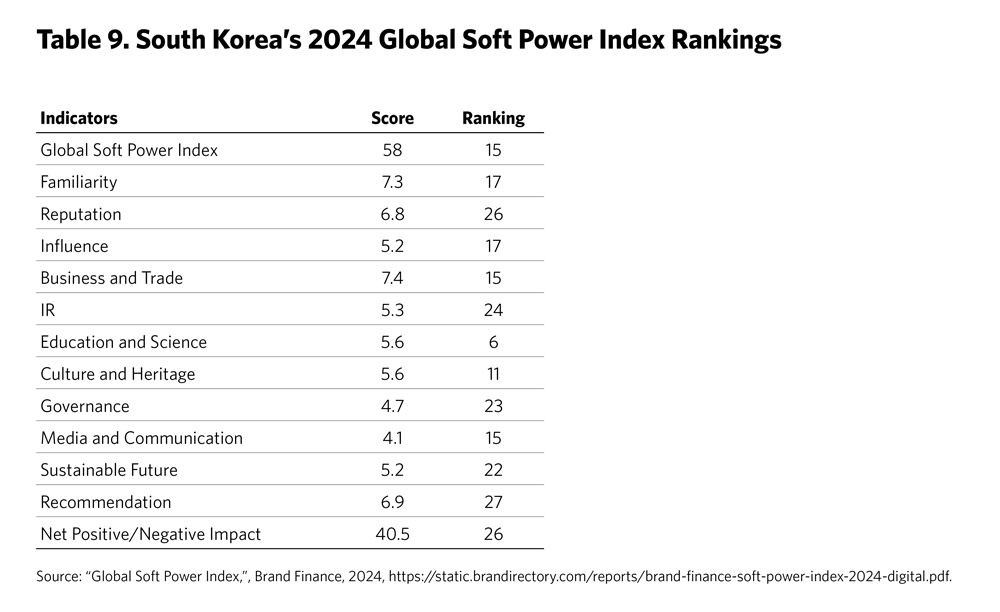

Today, South Korea’s economy boasts notable strengths including leading semiconductor manufacturers such as Samsung and SK Hynix that have become increasingly important players in the accelerating AI revolution. Seoul also has a formidable military, including an emerging defense industry that has provided billions of dollars in arms and munitions to members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) like Poland in the shadow of Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.10 If one adds in the growing popularity of K-pop and other types of South Korean cultural exports (such as movies, dramas, food, and fashion), the country’s hard and soft power have never been in such demand.

While there is no universal definition of power, the term is used here to refer to “the ability to act or produce an effect and a possession of control, authority, or influence over others,” the definition provided by Merriam-Webster.11 Measuring power is more of an art than a science, although key indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP), branding, technological prowess, military capabilities, total trade, level of education, governance structures, and depth and availability of universal healthcare provide a fairly accurate depiction of a country’s global standing. This study uses the term “K-power” to refer to a holistic understanding of the various strands of economic, technological, military, and cultural power that Seoul must harness to meet the challenges ahead.

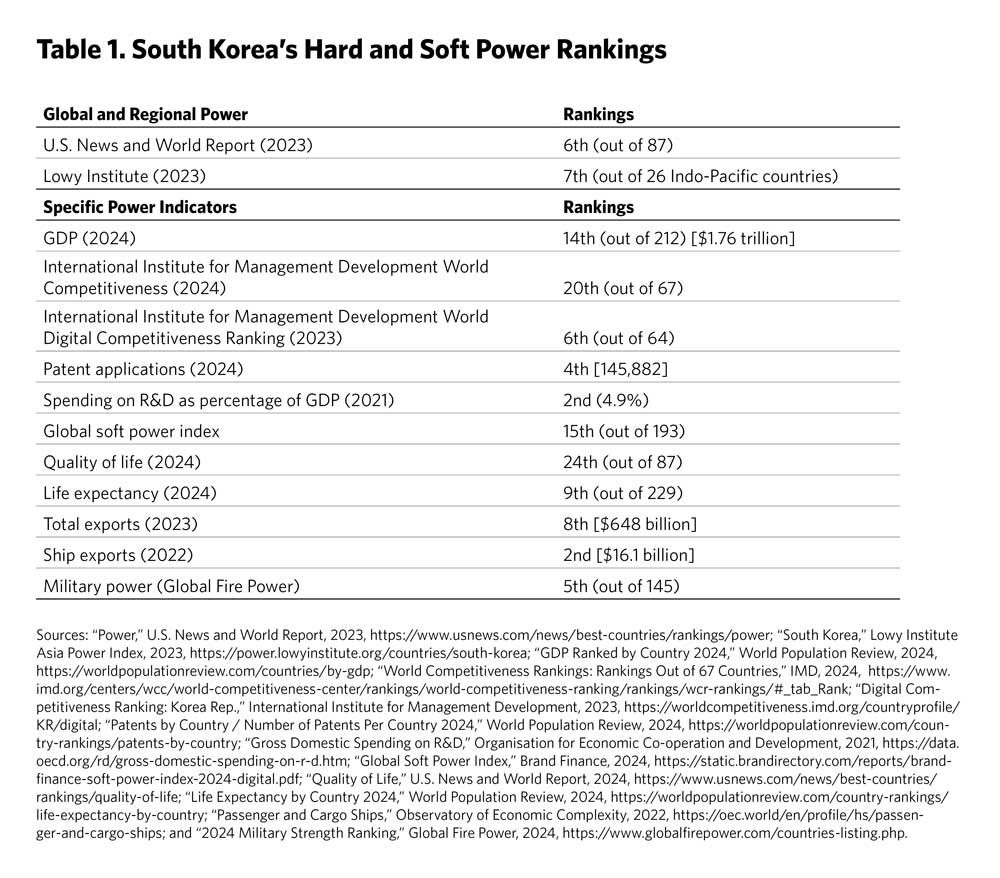

According to a 2023 study by U.S. News and World Report, South Korea ranked sixth in total power among the eighty-seven countries included in the study.12 As seen in table 1, South Korea ranks in the upper echelons of states on a range of metrics including GDP and exports, shipbuilding and other advanced manufacturing, military power, soft power influence (due in part to the popularity of K-pop and Korean cinema), life expectancy, and global competitiveness.

Despite the advantages of South Korea’s economic strengths (including its manufacturing prowess), its world-class high-tech industries, its formidable military, and its enviable soft power, Seoul faces severe headwinds. The country’s demographic trajectory poses the most critical challenge. South Korea’s population in 2022 stood at 51 million, but the country has the lowest fertility rate in the world (0.72 expected babies per woman); this figure continues to drop, and the country also has one of the fastest-aging populations among the world’s developed economies.13 About 19 percent of South Koreans are sixty-five years or older, and in 2023, those in their seventies outnumbered those in their twenties. South Korea is on the cusp of becoming a super-aged society, a benchmark reached when 20 percent of a country’s people are sixty-five or older.14

One of the reasons for South Korea’s rapidly falling birthrate is a decline in marriages over the past fifty years. According to Statistics Korea, the number of marriages per 1,000 people reached a peak of 10.6 in 1980 but was only 3.8 in 2023.15 The number of divorces was 92,400 in 2023, a slight decrease of 0.9 percent from 2022.16 But with the country’s rapidly aging population, so-called gray divorces among people ages sixty and older are on the rise. The most recent data shows that 16 percent of all divorces in South Korea involved couples who had been married for thirty years or more.17 With longer life expectancies, changing social norms, and stronger support for women pushing for a more balanced distribution of household work, the divorce taboo in the country has weakened considerably over the past four decades.

There are also clear signs that the pressures of the extremely competitive nature of the South Korean workplace and educational system are taking their toll. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, South Korea had the highest suicide ranking in 2020 at 24.1 per 100,000 persons.18 Many factors are likely at play, including the falling living standards of retired persons (especially men), mounting financial difficulties following the coronavirus pandemic, intense competition to enter the country’s top universities, the proliferation of costly after-school cram schools, and the infamously long hours of South Korean workers.19 Moreover, the growth in smaller families or even one-person households has also contributed to mounting loneliness among South Korea’s aging population.

While office working cultures have improved somewhat, South Korean companies (like their Japanese counterparts) remain very hierarchical with top-down management styles. Work-life balance is getting increasing attention as South Korea has entered the ranks of high-income countries, but the pressure for young people to shoot for the best universities and to work at leading companies continues to persist. South Koreans worked more than 1,900 hours per year in 2022, or about 150 hours more than the average for countries in the OECD, though there has been a downward trend over the past decade.20

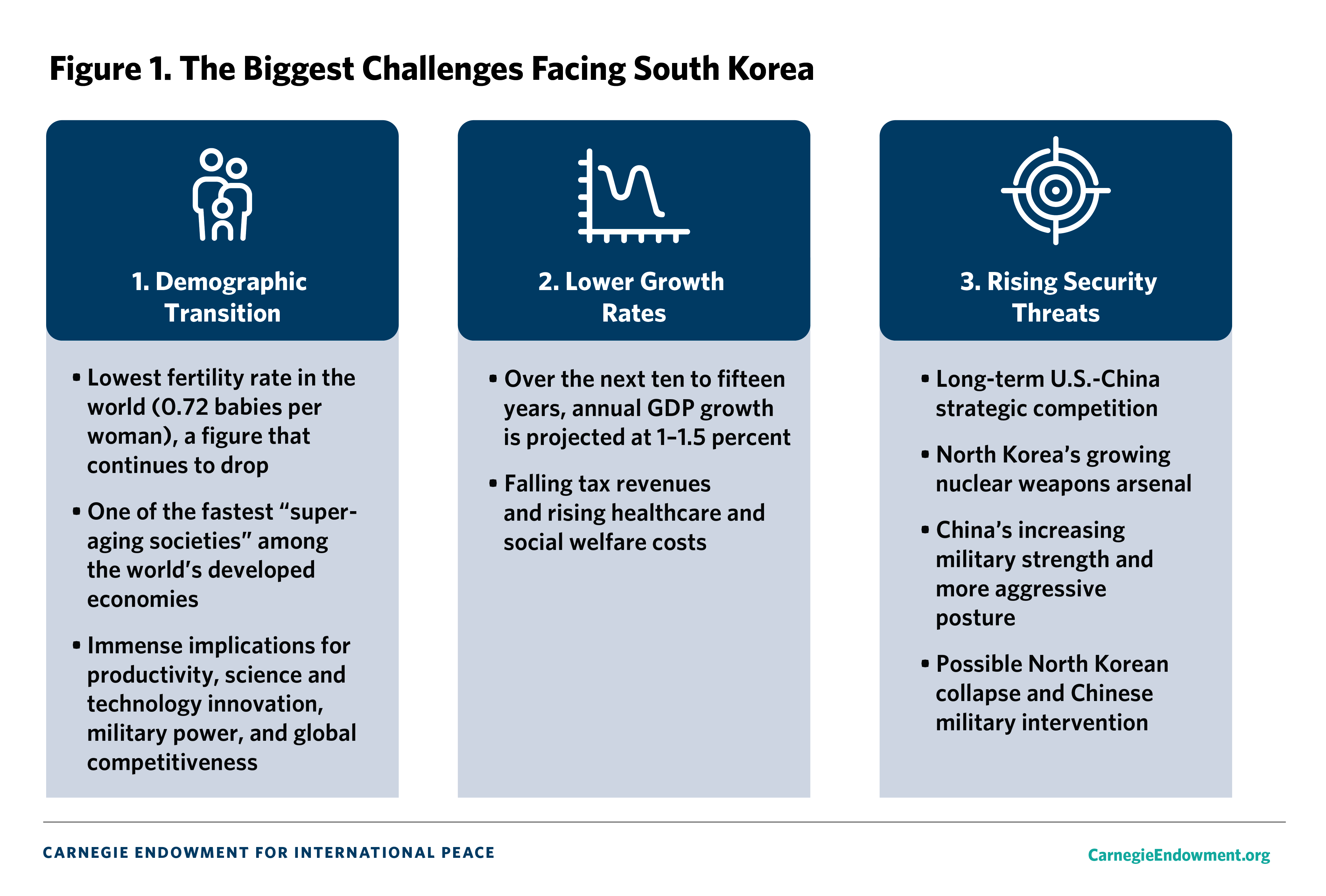

These demographic figures and societal challenges cast a long shadow over South Korea’s economic future. According to a long-term projection made by KDI, the country’s baseline average growth rate was expected to be 1.9 percent between 2023 and 2030, 1.3 percent between 2031 and 2040, and a mere 0.7 percent from 2041 to 2050.21 Compared to the double-digit GDP growth that South Korea often achieved between the mid-1960s and the late-1980s, South Korea’s future economic growth looks increasingly like Japan’s anemic growth: Tokyo has garnered at least 2 percent growth in only seven of the past thirty years.22 Overall, South Korea faces three major challenges as illustrated in figure 1.

If these structural problems weren’t enough to hold back South Korea’s future power potential, the country’s role as a key middle power in Asia exposes it to the economic and geopolitical risks of being caught in the center of worsening tensions and competition between the world’s two superpowers, the United States and China. India, Indonesia, and Vietnam are also key competitors as their economies develop.

In addition, Seoul’s neighbor to the north poses the most severe security threat and source of instability on South Korea’s doorstep. Although developments in North Korea are extremely difficult to forecast, including projections of the resilience of the Kim dynastic dictatorship, the possibility of severe political turmoil following potential regime or state collapse cannot be dismissed. South Korea must also contend daily with North Korea’s nuclear arsenal and its 1.1-million-strong military on the other side of a border just 50 or so kilometers north of Seoul—the capital and heart of South Korea with its 10 million inhabitants.23 Even as social welfare, healthcare, and educational costs continue to rise—together making up some 50 percent of the South Korea government’s roughly $500 billion budget for 2024—Seoul continues to spend more than $40 billion on defense.24

Under the world’s only family-based Communist dynasty and a totalitarian state that continues to spend between 20 and 30 percent of its GDP on defense to accelerate its nuclear weapons and other WMD programs, North Koreans have weathered endemic food shortages, malnutrition, and destitute living conditions.25 In 2022, the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff and Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that North Korea spent a total of $560 million on ballistic missile launches in 2022—more than enough to cover the estimated $417 million needed to fill North Korea’s annual food gap and keep the country’s population fed.26 In September 2022, Voice of America reported an estimate of the costs of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program: between $1.1 billion and $1.6 billion since Pyongyang’s first nuclear test in 2006, according to a study by the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses, the main think tank of the Ministry of National Defense (MND).27 If one adds those costs, it’s very clear that North Korea is choosing to develop increasingly more powerful WMD weapons rather than to feed its population. For now, however, Kim has gotten a small second wind by supplying Moscow with much-needed munitions and receiving food, fuel, arms upgrades, and consumer goods from Russia.28

Aside from these pressing economic and security challenges, South Korea also faces hurdles to ensure that the country’s impressive exporting of cultural products keeps the hard-won momentum gained in recent years through the popularity of K-pop and hit South Korean films like Parasite and television shows like Squid Game. Sustaining South Korea’s cultural attractions depends on a wide range of factors including constantly developing new content, reducing reliance on cookie-cutter K-pop groups, building stronger cultural brands, and facilitating tourism and work-study programs.

South Korea is no stranger to challenging geopolitical conditions. It has faced immense challenges since the Korean War (1950–1953), including economic ones. The oil crises of the early to mid-1970s, political turmoil and an economic downturn in 1979 and 1980, the outbreak of the Asian economic crisis from 1997 to 1998, and the global financial crisis in 2008 are among the most visible economic perils South Korea has had to overcome. As in the past, South Korea does not have abundant natural resources; it imports nearly all its oil and natural gas, remains highly dependent on exports, and is situated in one of the most dangerous geopolitical regions in the world.29 These factors won’t change.

What is going to be crucial for the rest of the 2020s is whether South Korea’s political leaders, corporate executives, technocrats, rising entrepreneurs, and educational leaders are willing to consider fundamental changes to how the country and its economy create and wield different sources of power.

Implementing long-term reforms across successive administrations with extremely divergent ideologies is a major bottleneck confronting South Korea. However, if the country’s economic and political stakeholders continue to rely on business-as-usual approaches, K-power will not only peak, but begin to decline rapidly with enormous economic, political, military, and social consequences. While accurate forecasting is extremely difficult, three main scenarios can be projected for South Korea.

Scenario 1: Innovating Korea: A key question is whether South Korea can adroitly adapt itself to the AI revolution and undertake key reforms in industrial policy, governance, and (most importantly) a strategy for enhancing the use of unmanned systems (referred to in the U.S. military as manned-unmanned teams [MUM-T]) and for incorporating AI-driven autonomous platforms to mitigate and (if possible) overcome the country’s demographic challenges. If Seoul can do so, it could emerge as a key global model. Expanding robot-based healthcare for the elderly is going to depend on the degree of social acceptance, facilities that will be able to handle robotic and online healthcare, and breakthroughs in wearable technologies. Even if South Korea opens its doors to significant immigration—an unlikely prospect for the foreseeable future—expanding robot-based healthcare is going to become crucial.

How South Korea copes with a dwindling farming population, redesigns of major urban centers, and educational reforms to account for an imploding student population are also critical benchmarks for ensuring a spirit of constant innovation. The country has been an innovator before. Beginning in the early 1980s when South Korea laid the groundwork for shifting from analog to digital communications and moved to become an early adapter of high-speed internet, South Korea has become one of the most wired countries in the world.30 While Seoul will face steep competition in technological innovation from major powers like China, the United States, Japan, and key European Union (EU) states, if South Korea manages to capitalize on its strengths as an early adapter of emerging technologies, a cultivator of a highly trained workforce, and an innovator that already prizes automation, the combination of these factors could give the country an important edge in an era that will be marked by massive AI-driven disruptions.

Scenario 2: Peaking Korea: Even though South Korea enjoys considerable global prestige due to its advanced economy, powerful armed forces, and magnetic pop culture, its population is also aging very rapidly.31 Japan and other advanced economies face similar population trajectories, but Japan has a much larger domestic market, a bigger world-class ecosystem for technological research and development (R&D), and more extensive global networks. Even under the best of circumstances, the South Korean economy most likely will grow between 1 and 2 percent over the next twenty to thirty years even as it weathers rapidly increasing social welfare costs, declining tax revenues, and lower productivity.32 Overall, if South Korea’s aging population and tepid growth play a defining role over the next two decades, the country’s national power is likely to experience a steady decline. In this scenario, while South Korea would still retain competitiveness in certain areas such as semiconductors and shipping, for example, its overarching national power would be highly unlikely to fully recover after peaking in the 2020s.

Scenario 3: Struggling Korea: Worsening geopolitical conditions such as long-term instability in the Middle East, including the oil-rich Persian Gulf states, would have major repercussions for the South Korean economy given its heavy dependence on imported oil and natural gas.33 Mounting tensions between the United States and China over Taiwan, intensified naval and maritime competition in the South China Sea, and a high-tech U.S.-China arms race could have severe spillover effects for South Korea. If these challenges coincide with a persistent and worsening South Korean political divide, the country’s existing social contract can only weaken. And if its demographic cliff cannot be mitigated or its deep-seated reservations about more open immigration changed despite intensifying labor shortages, South Korea’s labor and manpower deficits will affect every sector of the economy as well as the national security domain, since the military won’t be able to meet minimum conscription requirements.

South Korea’s cloudy economic outlook could be exacerbated by major security problems. Across the border, while North Korea might remain firmly under Kim’s control, he could face growing socioeconomic challenges as he prepares one of his children (such as his teenage daughter Kim Ju Ae) to be the fourth leader of the Kim family’s hereditary dictatorship.34 The Kim regime would likely continue to rely on China for economic and political support, but Beijing might be unwilling to provide extensive aid, leaving North Korea’s already struggling economy in potentially dire straits.

While it’s beyond the scope of this study to delve into the potential future trajectory of North Korea, the Kim regime’s biggest threats are increasingly coming from within, such as a population that is no longer willing to endure massive food shortages while the country’s few select party and military elites have no empathy for the masses. And because of the rapid proliferation of cell phones, laptops, and flash drives in North Korea (despite the fact that the internet is banned), access to information, entertainment, and news from the outside (mainly from South Korea but also from China) has increased dramatically over the past two decades. The net result is likely significantly weakened ideological unity and indoctrination that no longer appeals to North Korea’s youths or the so-called “Jangmadang Generation,” who survived and grew up without government support and relied almost exclusively on private markets.35

The growing number of crackdowns on those who are caught watching South Korean movies and dramas and using South Korean words offers further evidence of Kim’s worsening ideological grip.36 Many have been sent to reeducation camps or, in many cases, executed for watching enemy propaganda. As a result, even though South Korea focuses correctly on responding to North Korea’s growing nuclear arsenal as an existential threat, it must also prepare for a range of other scenarios within North Korea, including regime collapse, that would have immense implications for South Korea.

Elements of all three scenarios are going to be visible in the South Korea of the 2030s and 2040s. But can a country be innovative, peaking, and struggling all at the same time? The preferred outcome is an innovative and constantly adapting country that can successfully mitigate the risks of peaking power and manage its rising social welfare costs. None of the core trends, such as South Korea’s demographic cliff and rising geopolitical tensions, are going to go away. Hence, the more apt question is what solutions or mitigating factors a future South Korea can realistically engineer and how readily it can implement them. If deep political logjams frustrate efforts to pass much-needed structural reforms—such as preventing the hollowing out of pension funds by exponentially rising social welfare costs including healthcare (while also controlling the rise of such costs), passing business-friendly regulations to spur startups, and allowing increased immigration—South Korean power will probably peak and then decline rapidly from the early to mid-2030s onward.

One crucial bellwether is South Korea’s ability to stem the implosion of its fertility rate, which stands at 0.72 babies per woman today and is expected to drop further to 0.68 by the end of 2024.37 Reversing South Korea’s sinking birth rate is an extremely difficult task, as other similar countries (like Japan) have shown. But providing affordable housing, significantly expanding daycare facilities, and reforming one of the world’s most intense and costly private educational systems will be crucial if South Korea is to keep its rapidly falling birth rate from dropping further. The critical litmus test for the future of K-power is internalizing South Korea’s falling birth rate as an existential national security issue that is as significant, if not more so in some ways, as responding to a nuclear-armed North Korea.

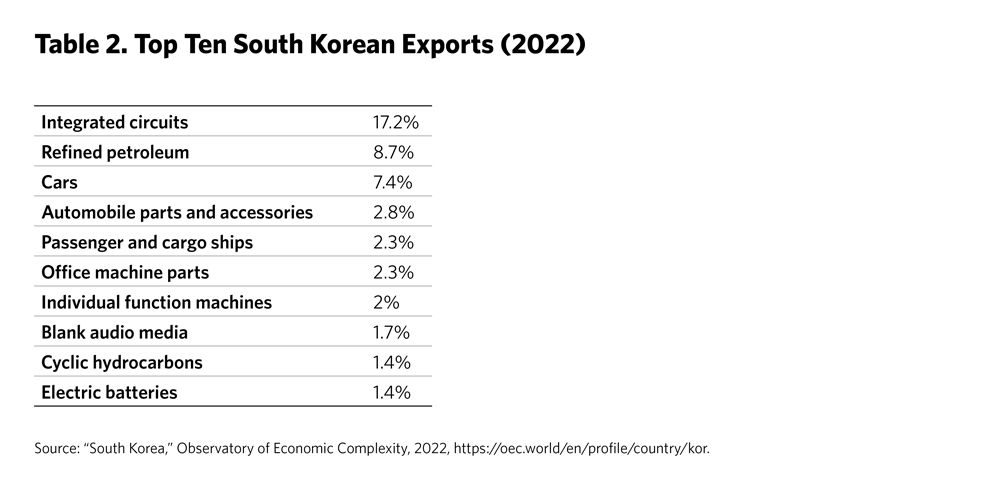

Considering the many constraints that South Korea’s economy is facing, a key issue is whether the country can continue to develop new sources of economic and technological power. Given South Korea’s status as an exporting powerhouse, it is impossible to imagine its economic future without exports. As shown in table 2, integrated circuits, refined petroleum, and cars together accounted for one-third of South Korea’s total exports in 2022.

While South Korea is one of the world’s leading exporters of advanced manufacturing goods (including semiconductors, consumer electronics, cars, ships, and key defense systems) and while Seoul’s services exports have grown, it still lags behind the United States and other advanced economies such as Japan and the United Kingdom (UK) in service exports. South Korean service exports grew from about $120 billion in 2021 to around $130 billion in 2022 to reach a total of 15.8 percent of total exports, but this share still was only about half of the corresponding share for the G7 economies on average (29.9 percent).38 Overall, manufacturing accounts for about one-quarter of South Korea’s GDP, one of the highest rates among the advanced economies, while services in 2021 accounted for 57 percent of South Korea’s GDP compared to 77.6 percent in the United States, 69.5 percent in Japan, 62.9 percent in Germany, and an OECD average of 71 percent.39 Coupled with the fact that South Korea imports nearly all of its oil and natural gas, the country remains highly vulnerable to major political and economic turbulences in key regions.40

But as the AI revolution begins in earnest, while South Korea should fully exploit the opportunities provided by AI-based or AI-enhanced manufacturing, it also has to ensure that it remains competitive in emerging global services markets, including science and technology research in key areas such as AI, quantum computing, new materials, clean energy, next-generation batteries and fuel cells, fintech, and advanced healthcare databases.

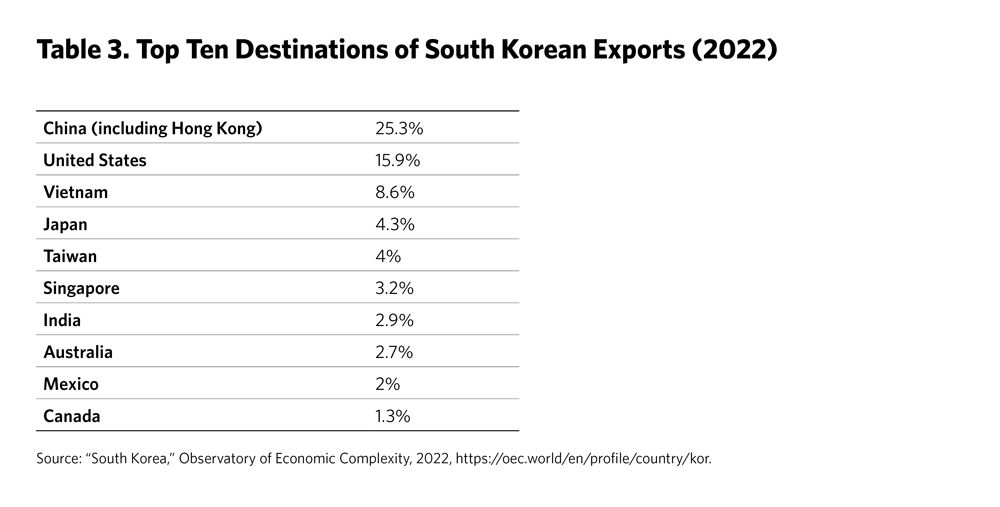

One increasingly important external factor that is affecting South Korean exports and outbound flows of foreign direct investment (FDI) is the growing U.S.-China economic and technology competition that has resulted in a realignment of critical global supply chains and derisking moves by South Korean companies. While South Korea’s exports to China have been dropping over the past two years, China still accounted for 25.3 percent of overall South Korean exports (including 4.1 percent to Hong Kong), followed by 15.9 percent to the United States, 8.6 percent to Vietnam, and 4.3 percent to Japan (see table 3).

South Koreans have major partisan policy differences on China—South Korean progressives favor closer political ties with Beijing, while the conservatives stress the importance of South Korea’s alliance with the United States and trilateral relations between Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington. Despite this, South Korea’s high-tech companies have more to gain by aligning themselves with the United States than with China in the growing U.S.-China tech competition. And as China faces mounting demographic and socioeconomic problems at home, it makes sense for South Korean firms to sharply decrease their dependence on the Chinese market. Given South Korea’s geographic proximity and heavy investments in China over the past three decades, it will take time for South Korean firms to shift investments to other economies. But one key factor that is going to spur South Korean companies to look elsewhere for future growth is the fact that Chinese companies are themselves global leaders in sectors like consumer electronics, electric vehicles (EVs), shipbuilding, and renewable energy that compete directly with all major South Korean conglomerates.

In 2023, South Korean exports to China fell for the first time since official relations were established in 1992. That year, South Korea also had its first trade deficit with China in three decades ($18 billion). South Korean exports to China dropped to $124.8 billion, or a decline of about one-fifth compared to the previous year.41 Still, as illustrated in table 3, South Korean exports to China (including Hong Kong) in 2022 amounted to about a fourth of South Korea’s total exports. The decrease in trade with China was offset by a 5 percent increase in South Korean exports to the United States in 2023, reflecting a shift in governmental policy to strengthen bilateral economic, technological, and security cooperation.

Part of Seoul’s recalculation has been driven by the Chinese government’s authoritarian tactics at home and its willingness to resort to economic coercion with its trading partners. While Beijing is conducting a charm campaign to entice greater foreign investment, General Secretary Xi Jinping’s harsh crackdown on China’s big tech firms and Beijing’s passage of the National Security Law in July 2015 have given the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) unfettered power over all companies based in China, including foreign firms.42

In March 2024, Hong Kong’s legislature passed Article 23, which supplemented a separate national security law that Beijing imposed on Hong Kong after antigovernment protests in 2020. This bill includes heavy punishments for foreign interference endangering national security, and it criminalizes the possession or disclosure of state secrets, measures that some foreign executives say could make the city less attractive for international businesses.43 A government spokesman responded to criticisms by stating, “enacting laws on safeguarding national security is an inherent right of every sovereign state . . . It is outrageous to single out Hong Kong and suggest that businesses would only experience concerns when doing business here but not in other countries.”44 But such official rebuttals often likely have the opposite effect, deterring foreign businesses from investing in Hong Kong (or for that matter, in China) because of the CCP’s increasing heavy-handedness toward its own major high-tech companies and threats to crack down on acts that are detrimental to China’s perceived national security interests.

Although South Korean companies continue to feel squeezed between the United States and China, it makes eminent sense for South Korean companies to lessen their dependence on the Chinese market because of the growing surveillance of foreign companies doing business in China. China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) announced in March 2024 that overseas spy agencies were using consulting companies “as a cover” to steal classified information that posed “major risks to national security.”45 The MSS warned,

[S]uch information, if accumulated to a certain extent and analysed in a comprehensive manner, can reflect important information about our economic operation, national defence and military, which are important targets coveted by overseas espionage and intelligence agencies, and once leaked, will seriously endanger national security.46

Worsening U.S.-China trade tensions and growing competitive frictions over technology have triggered a shift in South Korea’s long-term dependence on the Chinese market. According to the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper, Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong stated in a July 2023 forum that South Korea had a “deadly [addiction]” to the gains from trading with China in ways that made structural reforms more difficult. He added, “blinded by China’s cheap labor, which kept the share of manufacturing unchanged on the country’s [South Korea’s] industrial portfolio, the country [South Korea] has found itself late for [a] paradigm shift . . . [and] we should associate the recent decreases in exports to China not only with the growing tension between Washington and Beijing but also with the hidden causes of the country’s economic structure.”47

As noted above, South Korea’s major trading partners are in Asia and North America; even though ties with the EU have grown over the past decade, South Korea’s exports to Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, the UK, Italy, and France accounted for approximately 6.5 percent of total exports in 2022.48 And while Russia has threatened retaliation if South Korea ships arms to Ukraine, only a paltry 0.9 percent of South Korean exports were destined for the Russian market in 2022.49 (Seoul hasn’t sent any weapons to Ukraine as of early July 2024 because of legal restrictions on the exporting of armaments to conflict or war zones, although the government is examining whether it can do so in the aftermath of Russia’s signing of a new defense pact with North Korea in June 2024.) Prior to the outbreak of the full-scale Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, imports from Russia such as coal, naphtha, natural gas, and crude petroleum comprised “a little over 9 percent of South Korea’s imports by value and volume,” but South Korea’s fossil fuel imports from Russia dropped “from $13.2 billion in 2021 to just $5.5 billion last year [in 2023].”50

Although firms from the United States and other major Western countries are the preferred targets of the MSS, South Korean companies are also under surveillance given Seoul’s alliance with Washington and close U.S.–South Korean alignment on technology policy. Ironically, Xi and other CCP officials continue to parrot the official line that China is “open for business.” But as the New York Times noted in February 2024, “[China’s] crackdown has amplified the challenges of investing in China at a time when FDI in the country has fallen to its lowest levels in three decades, as companies are increasingly unwilling to endure the trade-offs of operating in China for an economy no longer growing by leaps and bounds.”51

In light of rising economic tensions between the United States and China and Beijing’s ongoing efforts to strengthen the CCP’s control over companies, South Korean corporations—like their counterparts in the United States, Japan, and the EU—are going to be even more wary of expanding their investments and business dealings in China. As the Wall Street Journal noted in April 2023, “Mr. Xi’s offensive against foreign businesses could threaten the government’s growth objectives at a time when some senior officials have grown worried that heightened geopolitical tensions are driving foreign investors and businesses away.”52

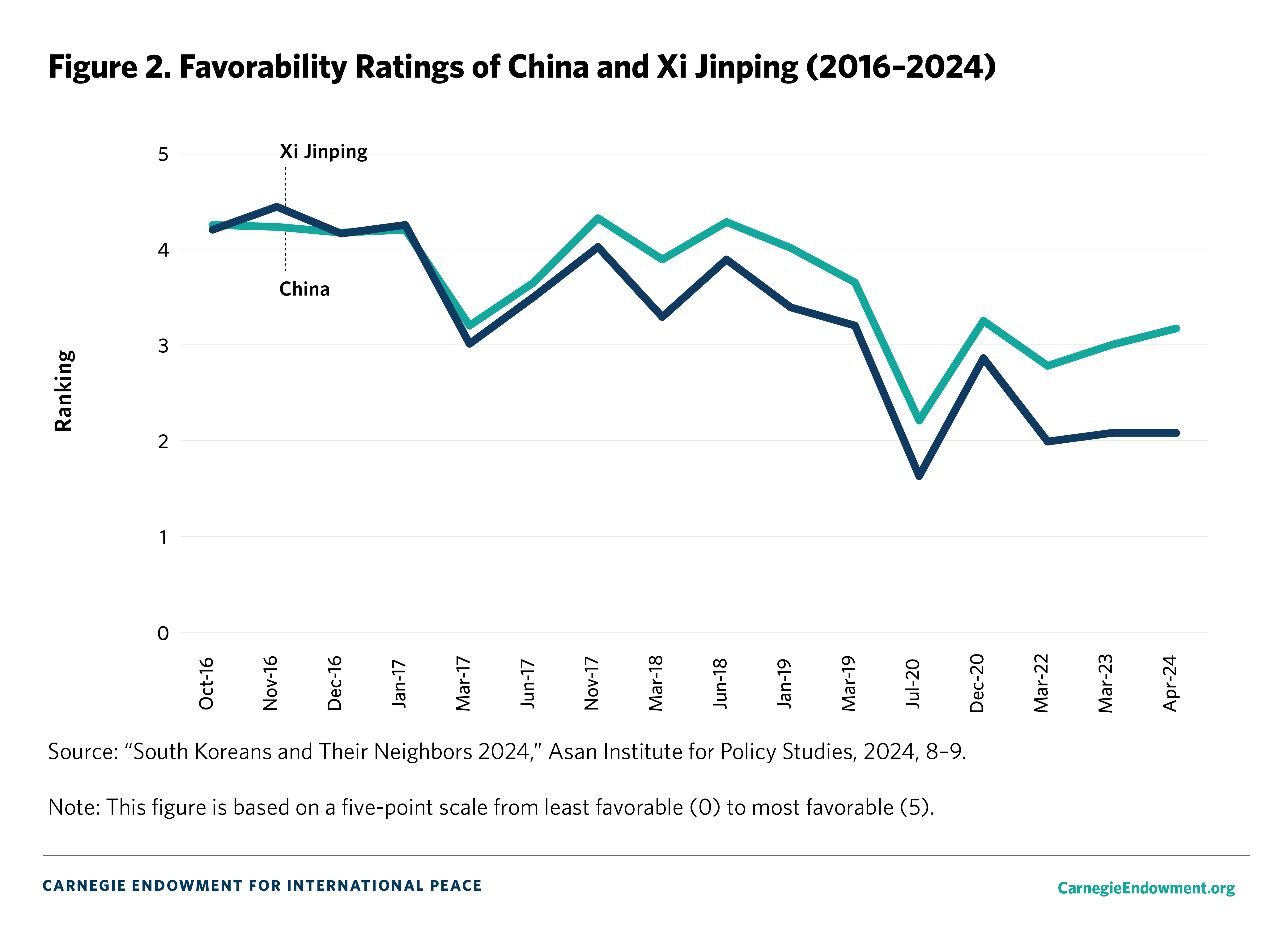

One major contributing factor to growing South Korean wariness of China is deepening anti-China sentiment among South Koreans. According to a survey released by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in November 2023, favorability ratings of China in South Korea dropped from 5.2 in January 2015 to 3 in March 2023. The rating system was based on a ten-point scale where 0 meant “not favorable at all” and 10 meant “very favorable.” As figure 2 illustrates, the favorability ratings of both China and Xi declined at about the same rate, but Xi had a lower unfavorable rating of about 2 in March 2023 compared to a high of 5.2 in January 2015.

A joint survey by the Central European Institute of Asian Studies and Sinofon released in 2022 showed that among respondents from twenty-three countries, South Koreans had the most negative perceptions of China, with 81 percent of all South Korean respondents reporting such views. This figure was higher than those for South Koreans’ negative attitudes toward other nearby countries, including Russia (77 percent), North Korea (69 percent), and Japan (62 percent).53

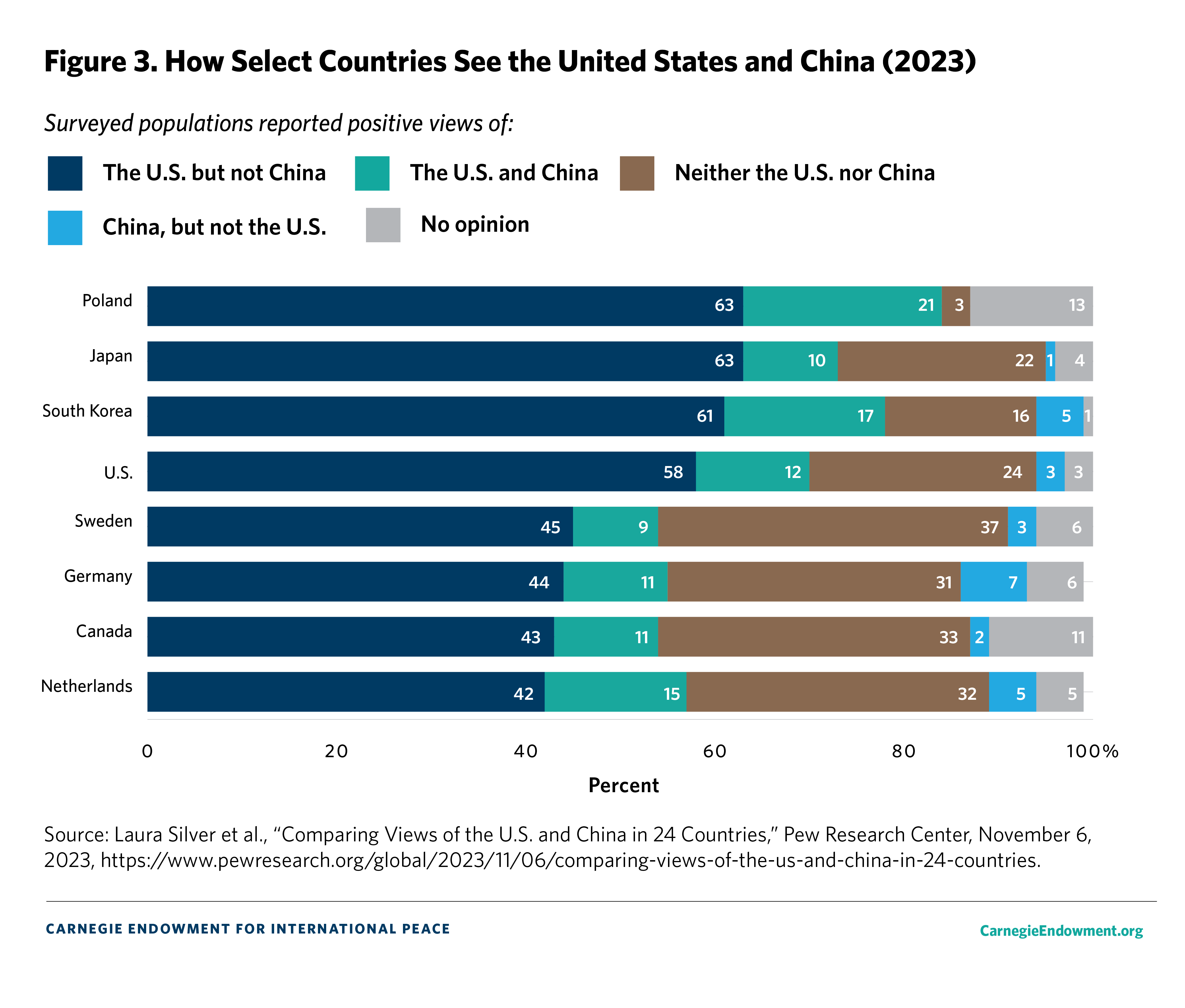

By contrast, nearly 75 percent of South Koreans polled in that survey had a positive view of the United States.54 In a separate Pew Research Center survey released in November 2023 comparing views on the United States and China in twenty-four countries, South Korea had the third-highest share of those who viewed the United States but not China favorably (61 percent) after Poland (63 percent) and Japan (63 percent). Only 5 percent of South Korean respondents said they had a favorable view of China but not the United States; meanwhile, 17 percent said they had a positive view of both China and the United States, and 16 percent said they didn’t have a favorable view of either the United States or China (see figure 3).55

Although there are multiple contributing factors to growing anti-Chinese sentiment among South Koreans, Beijing’s harsh response to Seoul’s decision to deploy U.S.-provided Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) batteries following North Korea’s sixth nuclear test in 2016 was a major trigger. At that time, China responded by boycotting major South Korean companies such as Lotte that invested heavily in China and pressured then president Moon Jae-in’s government into agreeing to the so-called “Three Noes” agreement—meaning no additional stationing of U.S. air defense systems; no strengthening of trilateral defense cooperation between Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington; and no South Korean participation in a U.S.-led missile defense system.56

When the Yoon administration came into office in May 2022, it argued that it would no longer abide by the Three Noes agreement Moon had made. Chinese officials have continued to lambast Seoul on the THAAD issue, including Beijing’s departing envoy to Seoul, Ambassador Xing Haiming, who stated in August 2022 that THAAD posed “the biggest challenge” to bilateral relations.57 Since taking up his post in Seoul, Xing has been infamous for his inflammatory remarks, often behaving as if he were a Chinese viceroy during the era of imperialist China, when the country’s representatives were empowered to make significant demands of host governments. During a meeting with opposition party leader Lee Jae-myung in June 2023, Xing said, “I can say definitely that those betting on China’s defeat will certainly regret it later.”58 In March 2023, during a campaign rally on behalf of the DP, Lee stated that South Korea should not be involved on the issue of Taiwan and that South Korea should just say “xie xie” (thank you) to the Chinese. Yoon’s ruling party immediately attacked his remarks as tantamount to being subservient to an increasingly aggressive China.59

While the THAAD issue has been a major factor in increasing anti-Chinese attitudes in South Korea, other developments also have been at play. For example, while tensions surrounding historical issues are usually the most visible in Korean-Japanese ties, historical disputes have also flared up between South Korea and China. For example, China claims that key parts of ancient Korea during the Goguryeo dynasty (37 BC–688 AD) were in fact Chinese, not Korean. South Koreans have reacted sharply to constant reminders of China’s cultural imperialism as well as rabid anti-Westernism among Chinese youths often with encouragement from the CCP.

Other factors have included severe sandstorms in China that have contributed to worsening air pollution in South Korea. As the BBC reported in April 2023, “Yellow dust is a seasonal ordeal for millions in North Asia, as sandstorms from the Gobi desert that borders China and Mongolia ride springtime winds to reach the Korean peninsula and this year, farther east to Japan.”60 However, it is also important to stress that air quality in South Korea, as measured by the concentration of fine dust called particulate matter 10, has decreased over time, and a study conducted by the South Korean National Institute of Environmental Research and the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 2022 indicated that “52 percent of the fine dust . . . in Seoul comes from domestic South Korean factories, while only 34 percent comes from western China.”61

Perhaps another major factor behind South Koreans’ increasingly negative views of China is the fact that South Koreans born after the democratization of South Korea in 1987 have much less affinity with China or North Korea.62 One indicator starkly illustrates changing South Korean sentiments toward China. According to the South Korean Ministry of Education, between 2017 and 2023 (a period that included the coronavirus pandemic), the number of South Korean students studying in China plummeted from nearly 75,000 to under 16,000.63

As South Korean exports to China have slipped, investments in the United States by South Korean firms have continued to rise over the past several years. In 2022, South Korean investments in the United States totaled $74.7 billion, an increase of over 5 percent compared to the previous year.64 In early 2023, major South Korean conglomerates such as Samsung, Hyundai, LG, Hanwha, and CJ (formerly CheilJedang) pledged to invest about $103.2 billion to build various plants in the United States or to buy stakes in U.S. companies.65 In 2022, U.S. trade with South Korea in goods and services totaled $224.4 billion, with $36.7 billion in U.S. investments in South Korea. Although South Korea enjoyed a trade surplus of $35.7 billion in 2022, its key role in the semiconductor, shipbuilding, and automobile industries has strengthened its profile as a critical supply chain partner.66

When the U.S. Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022, South Korean companies such as EV manufacturers were worried that they would face discrimination in favor of U.S. companies. But major battery manufacturers such as LG Energy Solution, SK On, and Samsung SDI have shown strong growth in the U.S. market, with a 27 percent jump in Korean-made EV batteries sold to the United States through November 2023. As South Korean companies have invested billions in new EV battery factories in the United States, the U.S. government is providing $11.7 billion in loans to them.67 According to one trade expert, “Despite the shortcomings of the IRA, it is providing significant benefits to Korea by expanding the market for clean energy products. Korean firms are leaders in many of these industries and now have access to tax credits to support sales and a combination of tax credits and loans to support production.”

In May 2022, Yoon and U.S. President Joe Biden released a joint statement that reaffirmed the importance of the bilateral security alliance but also stressed the growing importance of economic and technological collaboration. As South Korea’s global branding and influence has grown, so too has its role as an increasingly valuable ally that possesses a wide range of capabilities. For example, the two leaders stressed:

Fully recognizing that scientists, researchers, and engineers of [South Korea] and the U.S. are among the most innovative in the world, the two Presidents agree to leverage this comparative advantage to enhance public and private cooperation to protect and promote critical and emerging technologies, including leading-edge semiconductors, eco-friendly EV batteries, Artificial Intelligence, quantum technology, biotechnology, biomanufacturing, and autonomous robotics . . . Recognizing the importance of energy security as well as commitment to address climate change given the rapid increase of volatility in the global energy market as a result of Russia’s further aggression against Ukraine, the two Presidents will work to strengthen joint collaboration in securing energy supply chains that include fossil fuels, and enriched uranium, acknowledging that true energy security means rapidly deploying clean energy technology and working to decrease our dependence on fossil fuels.68 (Emphasis added)

Although specific developments will take several years and also depend on each country’s political climate, what is noteworthy is how much of the joint statement was devoted to nonmilitary areas compared to previous joint statements, where security and defense dominated bilateral summit discussions. To be sure, domestic political shifts in the United States and South Korea will affect how readily greater technological cooperation will be forged as the rest of the 2020s unfold, but as the AI revolution begins in earnest, South Korea’s closer alignment with the United States on critical technologies is likely to continue.

Clearly, there are question marks about both countries’ political futures. The April 2024 National Assembly election in South Korea resulted in a major defeat for Yoon and the ruling party. While the opposition DP and other minor opposition parties hold an overwhelming majority and generally are more antibusiness than the conservatives, the DP is unlikely to directly oppose growing South Korean investments in the United States.

Another major political uncertainty is former U.S. president Donald Trump’s possible victory in the November 2024 U.S. presidential election. He has already threatened to force allies to make up for trade deficits, increase defense cost-sharing amounts for allies such as South Korea, decouple from China, and continue to push for greater FDI in the United States.69

Nevertheless, even if Trump returns to power, South Korea has leverage, since key Korean companies have invested billions in plants and factories in swing states like Georgia and Michigan.70 And as South Korean investments in high-tech sectors such as chip plants in Texas expand, a second Trump administration would likely welcome growing South Korean investments in the United States.71

In December 2023, the South Korean Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy announced its 3050 Strategy Initiative, which was “designed to stabilize South Korea’s key supply chains and reduce dependence on China [for raw materials] to less than 50 percent by 2030.” As one Asia Times op-ed put it, “South Korea appears to be drawing away from China’s geoeconomic orbit as South Korean investment in the United States reinforces the geopolitical choices of the Yoon administration.”72 As South Korea seeks to lower its dependence on China, its companies are becoming critical to U.S. efforts to manufacture more EVs. South Korean firms are the number-two producer of EV batteries for the United States (18 percent market share) and boast “60 percent of the world’s non-Chinese battery capacity,” according to the Financial Times.73 Yet the same article points out that these South Korean firms have warned that less expensive imports of Chinese-made batteries could undercut their battery sales unless the U.S. government provides tax credits.74

In this regard, Samsung received welcoming news in April 2024 when the Biden administration announced that the firm would receive $6.4 billion in grants as Samsung plans to increase investments in Texas to $45 billion. U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo stated, “[these investments) will allow the U.S. to once again lead the world, not just in semiconductor design, which is where we do now lead, but also in manufacturing, advanced packaging, and research and development.”75

Yet the bilateral economic relationship is hardly a one-way street. In 2022, U.S. FDI in South Korea was estimated at $36.7 billion, although this figure had fallen by 10 percent compared to the previous year; meanwhile South Korea’s FDI in the United States in 2022 was $74.7 billion.76 As Seoul’s investments and exports have grown, South Korea has emerged as an economic partner of such major U.S. states as Texas and California. In 2022, South Korea was Texas’s fourth-largest trading partner with about $33.1 billion in two-way trade.77 In a turn of events that would have been unimaginable a decade ago, “South Korea is the #1 source country for capital investment created by FDI in Texas and the seventh-largest source for new jobs created by FDI,” according to the Texas state government.78 Economic ties with California have become similarly strong. South Korea was California’s fifth-largest export destination in 2022 as the West Coast state exported about $11.6 billion to South Korea, while South Korea exported about $31 billion to California; this two-way trade is dominated by “non-electrical machinery, computers and electronics, transportation equipment, and processed foods.”79

A critical potential litmus test on the durability of a U.S.–South Korean technology alliance is how a possible second Trump term would affect bilateral ties. When he was in office, Trump held three meetings with Kim, and he has said that he would be willing to restart talks with Kim if he wins in 2024. Contrary to the previous Moon administration’s policy of engaging extensively with Pyongyang, ignoring North Korea’s abhorrent human rights abuses, and even forcibly repatriating North Korean defectors, the Yoon administration has taken a much sterner stance toward the North. If Trump chooses to restart nuclear negotiations with Kim, it could result in the dilution of the U.S. commitment to South Korea’s defense (through potential steps such as canceling the Nuclear Consultative Group that Biden and Yoon created to strengthen U.S. extended deterrence), in which case ties between Seoul and Washington would fray.

But even a reelected Trump would need South Korean companies to continue to invest in the United States and to stay aligned with Washington in terms of counterbalancing Chinese economic and technological power. Hence, strengthening U.S.–South Korean economic ties, especially in semiconductors, EV batteries, renewable energy, and biopharmaceuticals, would be critical to containing the possible fallout from contrasting approaches to North Korea that could arise during a potential second Trump term and during the remaining three years of the Yoon administration. Jin Roy Ryu, who heads South Korea’s most powerful business lobby, the Federation of Korean Industries, told Nikkei Asia in January 2024 that U.S.–South Korean business ties won’t change even if there is a change in administration in the United States. Ryu noted, “while the Democratic Party supports American companies politically, Trump tends to welcome companies investing in the U.S. regardless of their nationalities . . . [and] South Korea, the U.S. and Japan must unite not only politically but also economically through their businesspeople, which the U.S. also wants strongly.”80

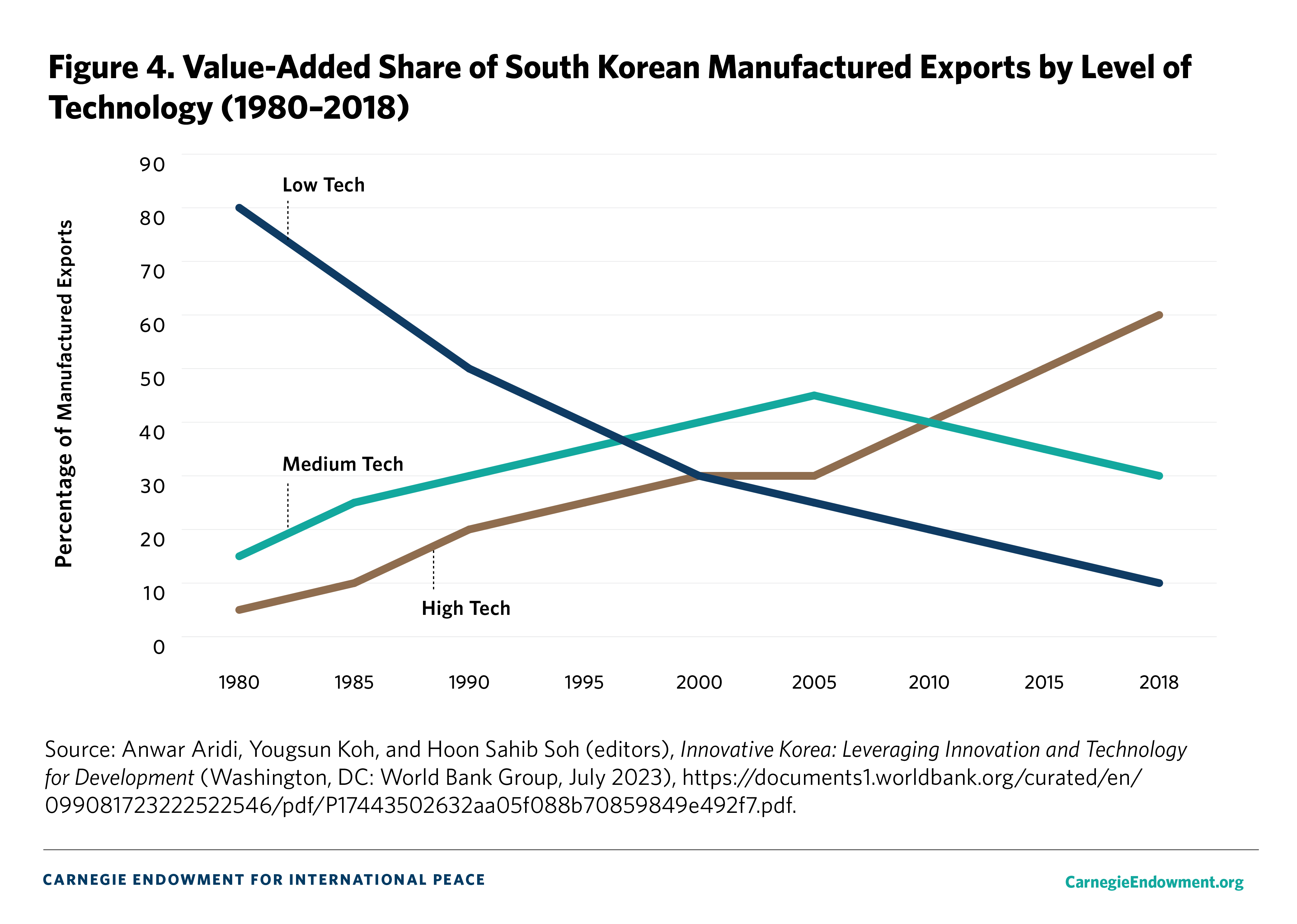

One of the most remarkable transformations South Korea has achieved is its rise as a technological powerhouse. When the country embarked on its first Five-Year Plan in 1962, its GDP was $2.8 billion and per capita GDP was $106. In 2023, South Korea’s GDP was $1.71 trillion and its per capita GDP was $33,121, according to World Bank data.81 Even when South Korea began to grow rapidly in the late 1960s and emerged as a major exporting economy in the mid-1970s, its overall technological level was low. As illustrated in figure 4, low-end technologies made up about 38 percent of the value-added share of South Korea’s total technology in 1980, while high-end technologies made up about 17 percent.82 By 2018, however, high-tech sectors accounted for between 40 and 50 percent of South Korea’s value-added share, whereas low-tech sectors’ share had dropped to about 10 percent.83

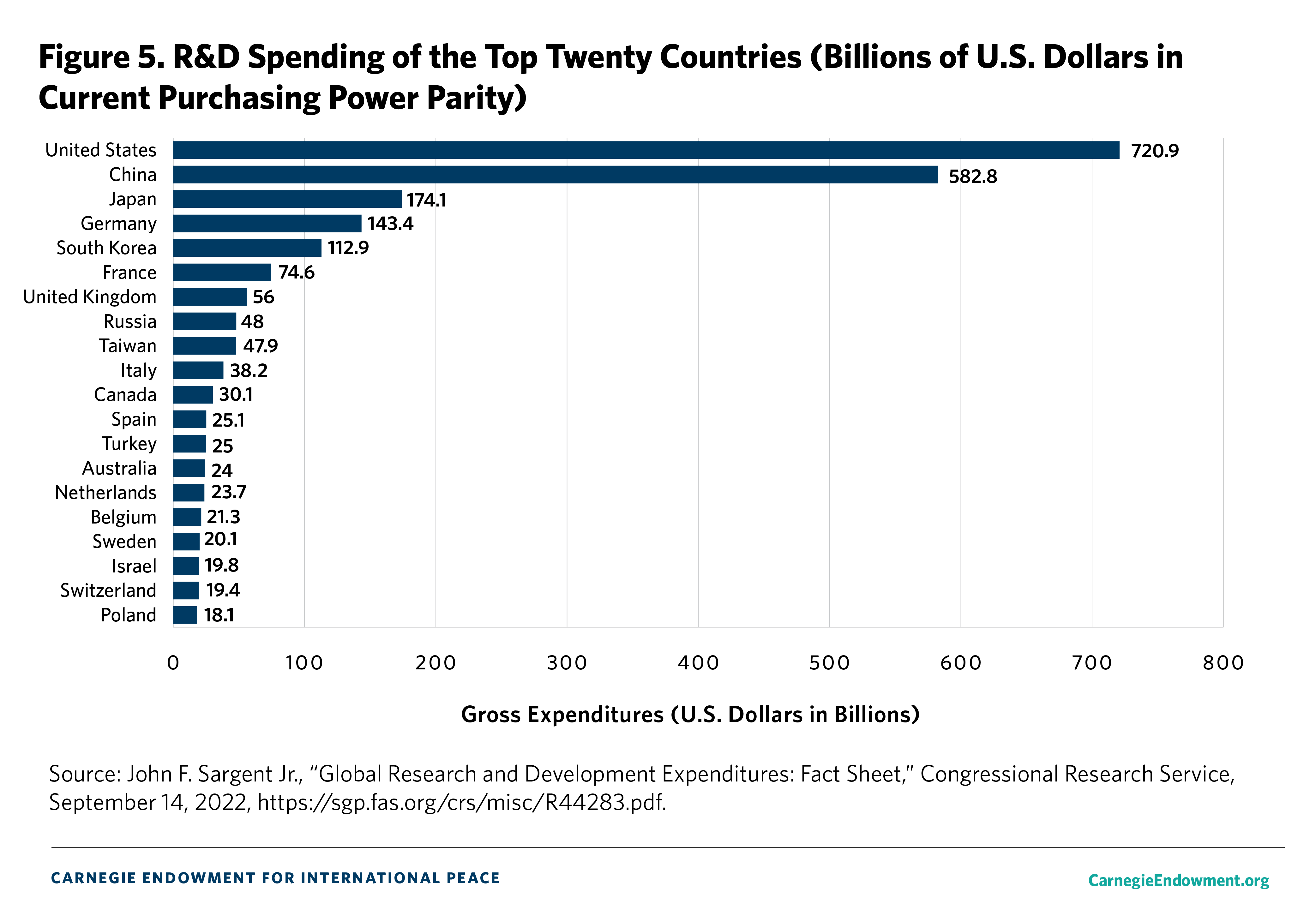

In light of the prominence of high-tech firms in South Korea, its standing as the country with the world’s second-highest R&D budget measured as a percentage of GDP (4.9 percent in 2021), its highly educated workforce, its advanced manufacturing industries, and its key role in many global supply chains, the prospects for sustained technological growth in South Korea remain relatively high.84 As figure 5 shows, in terms of real spending, South Korea spent $112.9 billion on domestic R&D and was among the top five countries worldwide for R&D spending in 2020 (in figures adjusted for purchasing power parity) behind the United States ($720.9 billion), China ($582.8 billion), Japan ($174.1 billion), and Germany ($143.4 billion).85 A 2019 study by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the National Science Board concluded, “South Korea’s ratio has . . . more than doubled from 2.13% in 2000 to 4.64% in 2019; its growth in R&D intensity has been particularly rapid since the late 1990s.”86

Like other advanced economies, South Korea does not want to be left behind in the race to harness promising technologies like AI, quantum computing, semiconductors, 6G networks, and virtual reality services and products. And although South Korea is a latecomer to the space race, Seoul is determined to ensure that it has a niche space market into the 2030s and beyond.

At the same time, however, South Korea faces enormous demographic threats such as the world’s lowest fertility rate and a rapidly aging population. South Korea could open immigration, introduce a wider class of working visas, provide incentives for retirees to reenter the workforce, and provide near-universal daycare for working parents. But all of these options face obstacles. There is limited political and social consensus on the question of increasing immigration. And if more retirees were to rejoin the workforce, that would leave even fewer job opportunities for those in their twenties and thirties. Meanwhile, South Korea also faces mounting social welfare costs during a period of lower tax revenues.

South Korea excels at demonstrating the pitfalls and possibilities of new technologies and the corresponding levels of social adaptability. In the automobile industry, South Korea has the highest density of robots (measured by the number of robots in operation per 10,000 human workers) with a figure of 2,867 robots in use as of late 2021 or “almost triple the average industrial robot density,” according to the International Federation of Robotics.87 The South Korean industry minister said in December 2023 that the government planned to invest $2.3 billion in the private sector “to bolster competitiveness of the local robot industry.”88 The government also plans to increase the number of service robots from 63,000 to 700,000 by 2030.89 Since 2017, industrial robot density in South Korea has grown at an annual pace of 6 percent in light of mounting labor shortages due to the country’s rapidly falling birthrate.90

In September 2022, the South Korean government announced a digital strategy that encompasses focused investments and developments in six key areas: AI, data integration, 6G networks, quantum computing, diverse digital platforms including the Metaverse, and inclusive digital transformation.91 In August 2023, RCR Wireless News reported that South Korea’s Ministry of Science and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) conducted a preliminary feasibility assessment of next-generation 6G network technologies and that its plan was to unveil pre-6G technologies by 2026 and to secure 30 percent of 6G global patents.92 The same article quoted the ministry as saying, “by the end of the project in 2028, in collaboration with major domestic corporations and SMEs, we aim to showcase the potential and vision of the 6G ecosystem and to secure competitiveness in the initial 6G market.”

Akin to earlier science and technology goals announced by previous South Korean governments, the Yoon administration released its science and technology roadmap in February 2024 in a strategy document entitled “New Growth 4.0.” As the leading body that oversees and decides South Korean science and technology policies, the Presidential Advisory Council on Science and Technology approved a blueprint with a focus on five key areas: “next-generation nuclear power, aerospace and ocean engineering, emerging communications, advanced robotics, and cybersecurity.”93

Given the global race toward mastering AI and quantum computing, Seoul plans to open a 20-qubit quantum computing cloud service in late 2024, and it aims to “develop 50-qubit quantum computer technology by 2026 and escalate to 1,000 qubits by 2032.”94 Whether Yoon’s science and technology programs will get sufficient funding depends on the upcoming budget battle with an opposition-dominated National Assembly; even if the DP supports the Yoon government’s science and technology budgets, the opposition will demand that its own priority agendas are also factored in. Moreover, while South Korea’s technology giants such as Samsung, SK, Hyundai, LG, Naver (a South Korean company akin to Google), and Kakao are all working on various aspects of emerging technologies, if the DP raises corporate taxes as it has threatened and seeks to curb the power of South Korea’s tech giants, that could stymie the country’s competitiveness in key sectors such as AI-driven innovation and R&D on quantum computing.

It is impossible to forecast precisely how South Korea’s science and technology ecosystem will change over the next ten to twenty years. Yet the country’s strengths as one of the most wired places in the world, its advanced manufacturing capabilities, and its status as an exporting powerhouse could help it become a key model for interacting with AI-based and AI-driven platforms. Such a dividend will appear, however, only after devoting significant resources to science and technology R&D; aligning South Korea with the United States, Japan, and key EU economies on critical technologies; and regulating AI to the extent possible while also seeking to foster business-friendly policies.

South Korea’s armed forces have made remarkable progress since the 1960s and early 1970s, when they were nearly totally dependent on U.S. weapons systems. Today, some rankings put Seoul in the upper echelon of military powers in the world. For instance, Global Firepower’s 2024 index ranks South Korea as the world’s fifth-most powerful military out of 145 countries—ahead of formidable countries like the UK (sixth), Japan (seventh), and Türkiye (eighth).95 From many perspectives, the South Korean military is a formidable fighting machine. It is armed today with an increasing array of sophisticated weapons, including a wide range of ballistic missiles, such as the Hyunmoo surface-to-surface missile, that can destroy key North Korean targets. South Korea’s armed forces are also very closely linked with U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) through the Combined Forces Command and the presence of 28,500 U.S. troops.96

But the South Korean military also faces key weaknesses. First and foremost, even though Seoul is under a U.S. nuclear umbrella, a second Trump presidency may result in key shifts, such as a gradual withdrawal of USFK at a time when North Korea is accelerating its nuclear weapons program. Second, even though the South Korean military is better educated, fed, supplied, and trained than North Korean forces, it faces one critical deficit: the fact that North Korea is a de facto nuclear-weapon state with other WMDs such as biological and chemical weapons. Third, changes in South Korea’s government between the left and the right have resulted in fundamentally different approaches to North Korea, particularly in the parties’ differing ways of assessing the range of threats emanating from North Korea.

And fourth, the last time that South Korean forces were engaged in extensive combat was during the Vietnam War more than half a century ago. This is not to suggest that South Korean forces must somehow be engaged in combat. But since they have not developed any significant battleground knowledge and experience, unlike their U.S. counterparts, South Korean forces have had to make up for that deficit with very intensive training and realistic counterstrike capabilities.

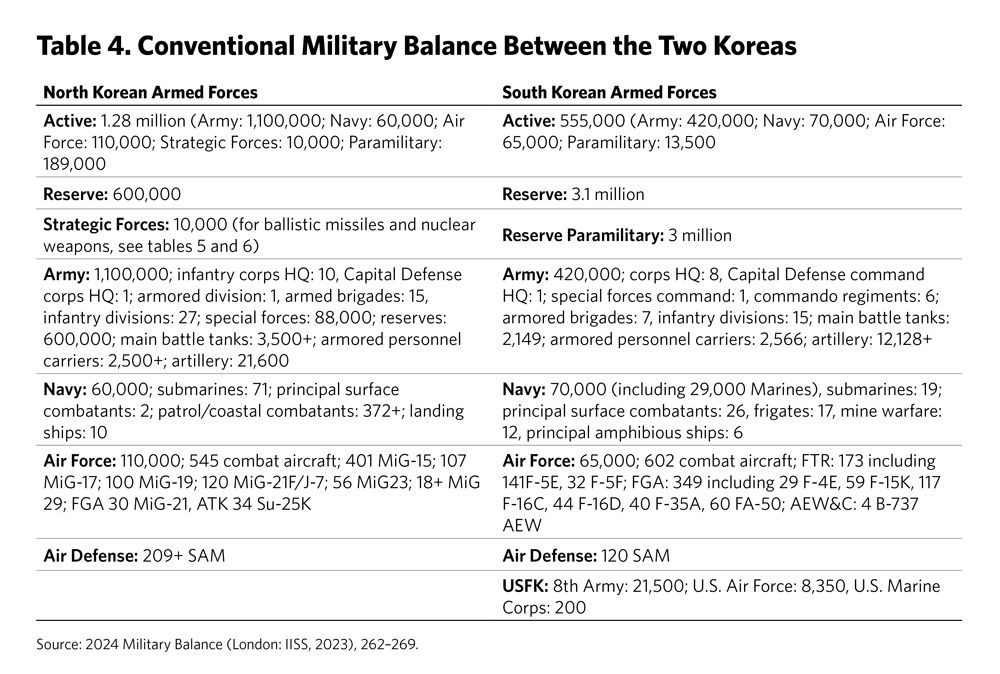

South Korea faces four main defense and security challenges. First, it must respond more effectively to North Korea’s sophisticated and growing nuclear and WMD arsenals and to China’s increasing power-projection capabilities (see table 4). Second, Seoul must help bolster U.S. extended deterrence by building stronger integrated deterrence capabilities and by thinking seriously about South Korea’s long-term deterrence options, including the need to prepare for nuclear threshold capabilities, policies, and strategies.

While there are contrasting definitions of what constitutes nuclear threshold policy, it refers to the strategy of seeking the requisite technologies and material to develop nuclear weapons but not doing so. For example, a senior Iranian foreign policy advisor, Kamal Kharrazi, stated in July 2021 that Iran “has the required technological capabilities to produce a nuclear bomb” but that the regime did “not want that” and had “not decided to do so.”97 In East Asia, many nuclear nonproliferation specialists consider Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to be “latent nuclear powers” or nuclear threshold states.98

Third, South Korea must shift to a force structure that operates under severe manpower deficits not only in the available pool of conscripts but among the noncommissioned officers (NCOs) that serve as the backbone of the armed forces. Fourth, the South Korean government should implement intelligence reforms to prepare actively for the AI revolution and the expanding nature of the threats confronting the South Korean military. Special attention should be paid to breaking down intra-service and intra-ministry barriers. Relevant factors include the National Intelligence Service’s ongoing efforts to lead imagery intelligence–sharing processes; competition between the MND and the Ministry of Science and ICT on designing next-generation intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms; and the need to foster much closer cooperation between the military, the intelligence community, and key companies to enhance the country’s ISR capabilities.

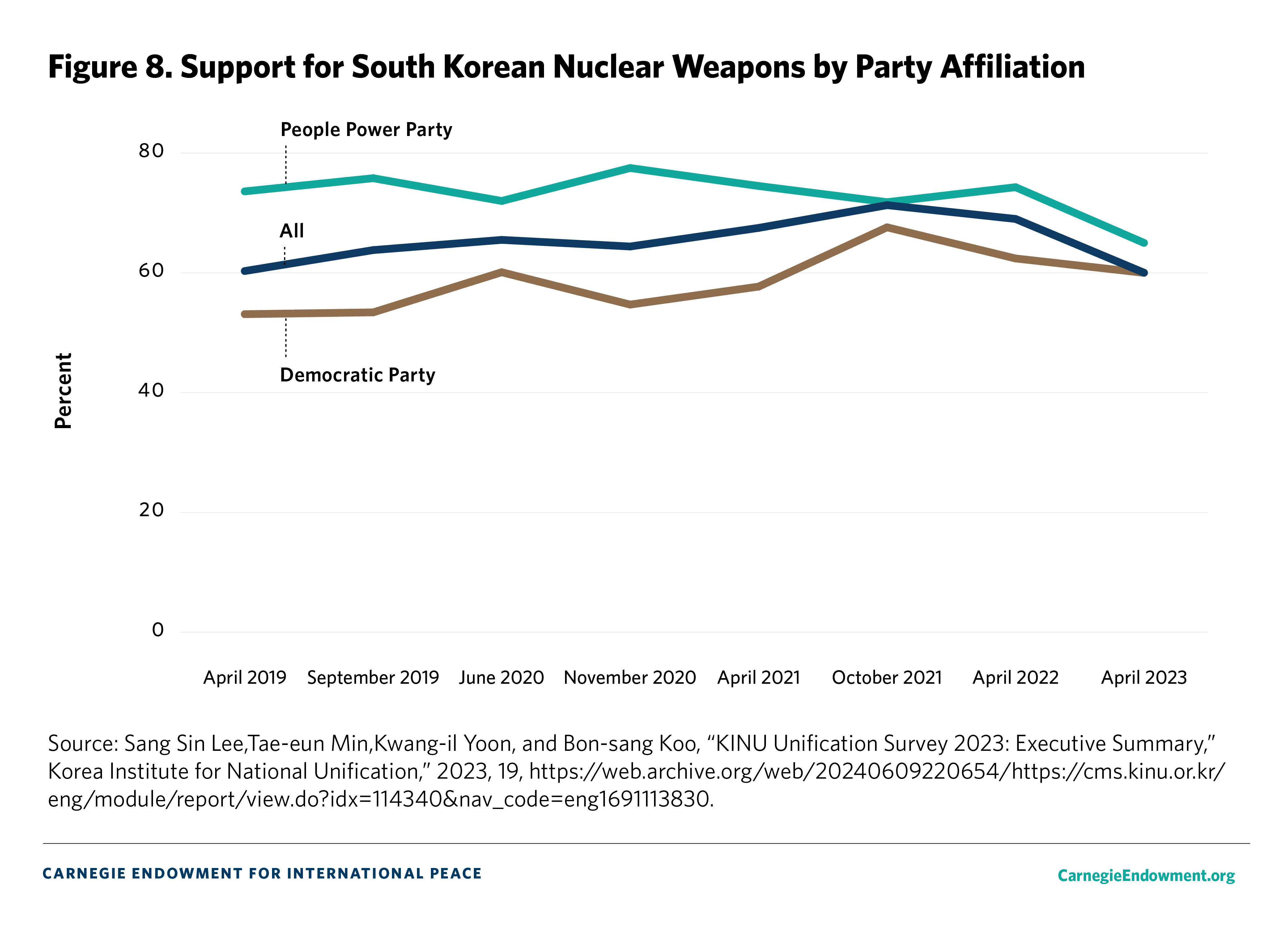

One of the most contentious defense issues in South Korea today is whether it should pursue its own nuclear weapons program. In a poll conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in February 2022, 67 percent of domestic respondents responded that South Korea should develop its own nuclear weapons, 24 percent said that there should be no nuclear weapons in South Korea, and 9 percent said that the United States should reintroduce nuclear weapons into South Korea.99 At the same time, 61 percent of respondents said that they remained confident that the United States would continue to defend South Korea, including with nuclear weapons.100 Yoon triggered alarm bells in the United States and beyond when he stated in January 2023, “if the issue [North Korea’s nuclear threat] becomes more serious, we could acquire our own nuclear weapons, such as deploying tactical nuclear weapons here in South Korea,” but he also cautioned that “it is important to choose realistically possible options.”101

There is very little possibility that South Korea is going to push through its own nuclear weapons program, given the impact such a decision would have on its alliance with the United States, the geopolitical and military repercussions, and even the economic consequences of potential international sanctions. But even though U.S. extended deterrence remains in place, a future U.S. president (such as Trump) may opt to withdraw all or part of the USFK. Moreover, during the 2016 campaign, Trump suggested that if South Korea and Japan pursued their own nuclear weapons program, it would be all right with him. In an interview with TIME magazine in August 2016, Trump noted that South Korea and Japan might need to develop their own nuclear weapons to protect themselves from China and North Korea and said, “if the United States keeps on its path, its current path of weakness, they’re going to want to have that anyway with or without me discussing it, because I don’t think they feel very secure in what’s going on with our country.”102 In the 2024 campaign, Trump has constantly criticized South Korea for being a defense free rider, although it pays roughly $1 billion annually for defense cost sharing. Nonetheless, Trump has repeated his claim, saying, “I told South Korea that it’s time that you step up and pay. They’ve become a very wealthy country. We’ve essentially paid for much of their military, free of charge.”103

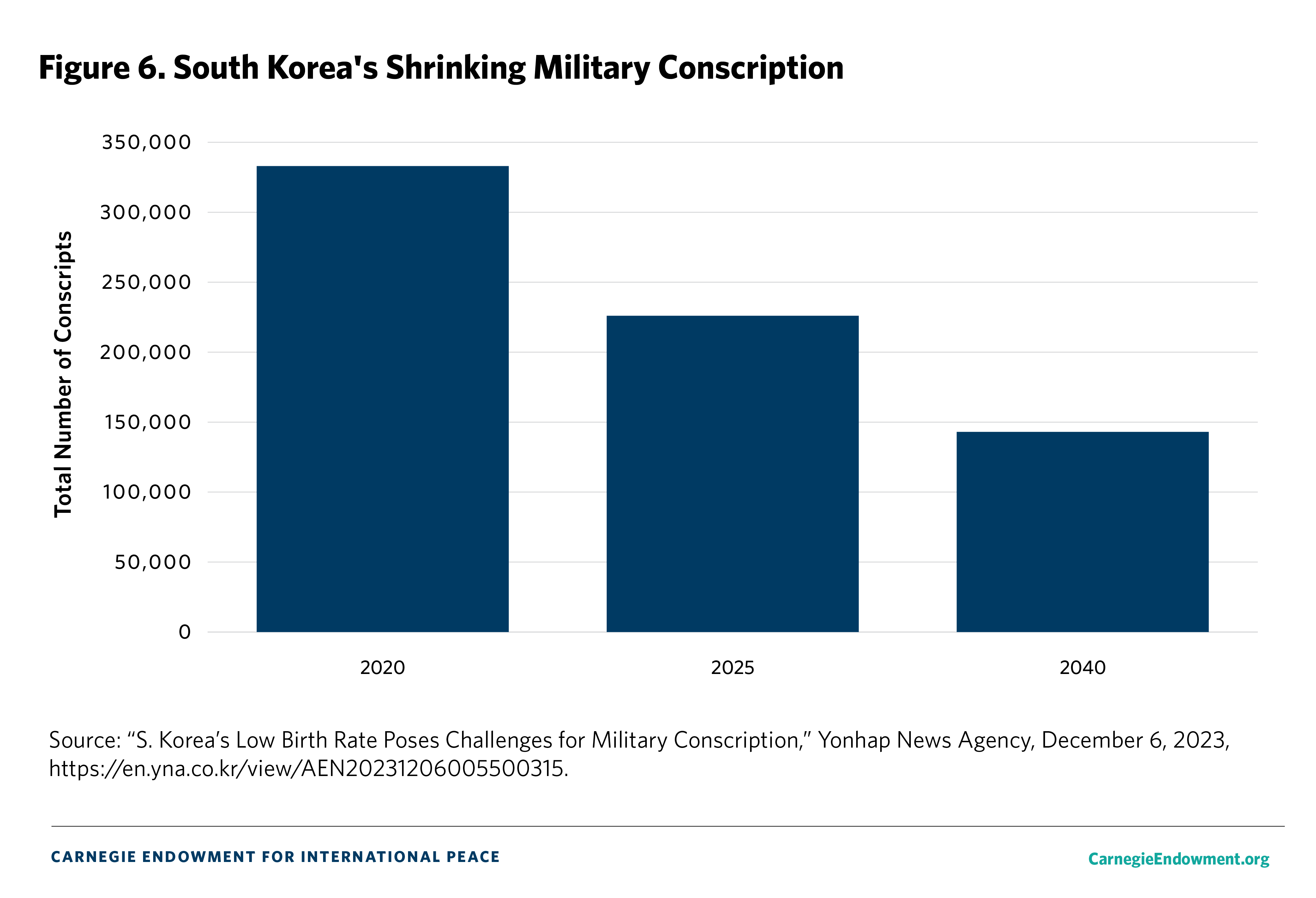

South Korea’s rapidly falling birth rate has critical implications for the country’s armed forces. The MND no longer sees the 500,000-force level as achievable, since the number of males available for conscription continues to drop (see figure 6). To maintain viable forces, the South Korean military needs to enlist 200,000 soldiers per year, but this is not going to be possible indefinitely with the country’s low birth rate.104 Since the armed forces knew that this manpower shortage was coming, the number of active troops was cut from 674,000 in 2006 to 500,000 in 2020. According to a South Korean military manpower expert, if South Korea’s low birth rate persists, as is likely, the “number of military personnel is expected to stay around 470,000 on average in the next 10 years.”105

To help mitigate this shortfall, the MND has stressed an infusion of AI and other advanced technologies including next-generation drones, unmanned platforms, MUM-T combat systems such as drone jets that can act as unmanned wingmen, submarine fleets that maximize the use of unmanned submersibles, and improved missile and artillery defense systems that use more autonomous early warning and response mechanisms.

But while technological add-ons will help, they will not fundamentally solve the problem of the country’s decreasing military manpower. Since South Korean women are exempt from military service, some analysts have called for the incremental drafting of women, but this idea has minimal support in the National Assembly. Although there is deep resistance to conscripting women, the South Korean military wants to increase the number of female volunteer soldiers. According to the Korea Times, “the ratio of female soldiers has risen from 6.2 percent in 2018 to 9 percent last year [2022].” The South Korean military has said, “given the sharp fall in the number of young males, the Army needs to consider various measures to address the personnel shortage, including the expansion of female military personnel.”106

The MND has argued that it can help offset these personnel shortages by recruiting and retaining commissioned officers, warrant officers, and NCOs; such personnel has grown to make up an increased share of the country’s military—rising from 31.6 percent in 2017 to 40.2 percent in 2022, and expected to rise further to 40.5 percent by 2027, according to CNN reporting. However, the problem lies in unattractive work packages. Recruitment of commissioned officers, for example, has fallen from about 30,000 in 2018 to 19,000 in 2022.107

The South Korean military’s manpower shortage is unlikely to be mitigated or improved anytime soon. Various options have been floated, such as selective conscription of women in nonlethal areas, increasing pay to provide incentives to NCOs to join and to reenlist, and allowing foreign nationals who can pass language and other tests and can then be eligible for citizenship through a South Korean version of America’s Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program. But options like conscripting women or exploring something like the MAVNI program have run into major political obstacles and are thus unlikely to stem the decline in military manpower.108

South Korea could become a global leader in adopting unmanned weapons systems and platforms to overcome, or at least partially mitigate, its severe manpower shortage. But to accomplish this end, the armed forces must implement massive structural reforms such as reducing the number of generals, integrating and merging similar units, and modernizing and streamlining command, control, communications, computers and ISR capabilities.

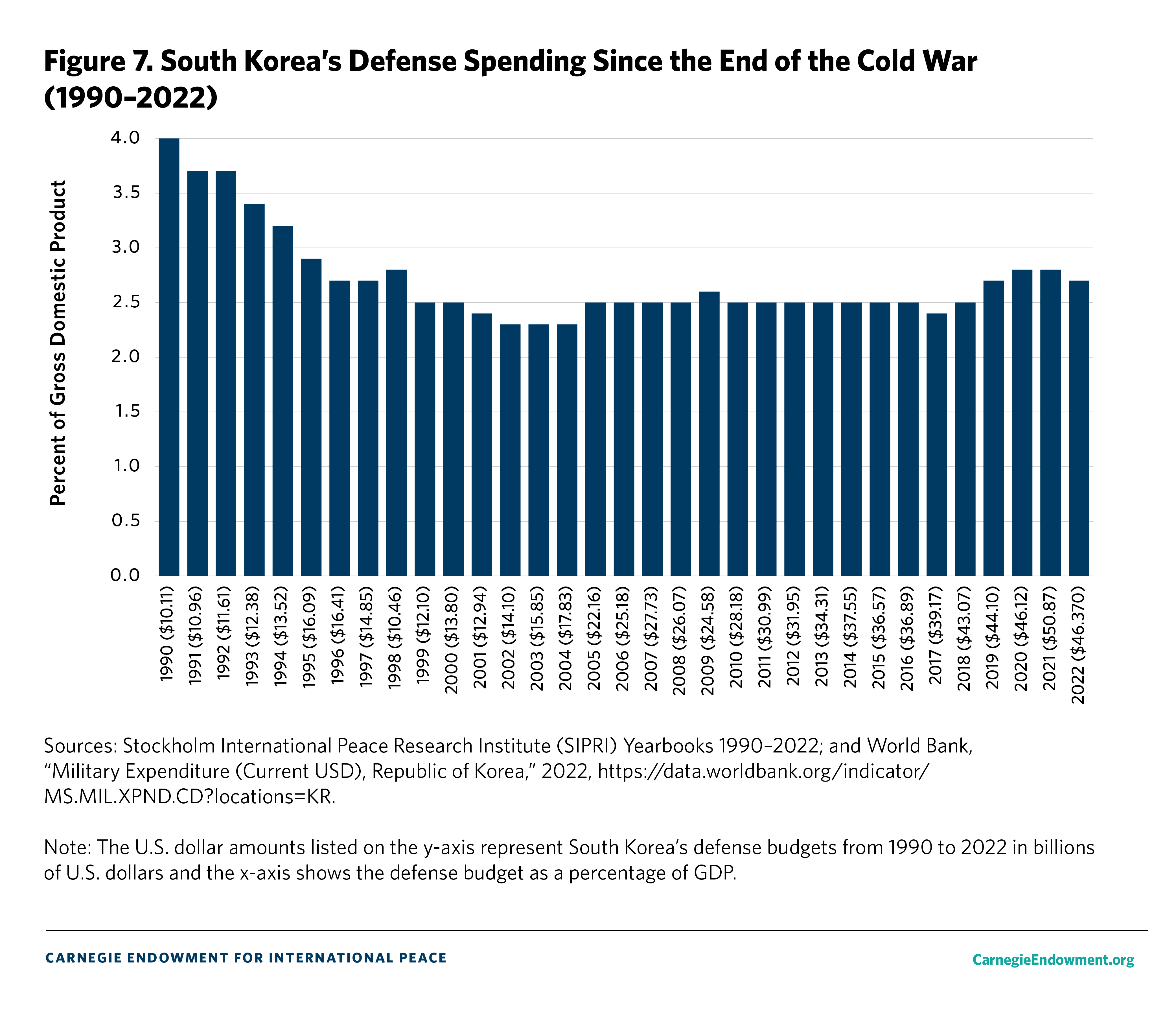

One additional constraint is whether the South Korean government will be able to continue to allocate the necessary resources for defense modernization and structural reforms with the country’s rising healthcare and social welfare costs. As illustrated in figure 7 below, South Korea has spent an average of about 2.6 percent of GDP on defense since 2005, but given Seoul’s need to upgrade its Three-Axis counterstrike and missile defense system, significantly increase wages for NCOs and junior officers, and upgrade its ISR capabilities, South Korea may have to spend even more on defense going into the 2030s. But worsening strategic and geopolitical realities are also going to run into the challenges of much lower levels of economic growth, lower tax revenues, and rapidly increasing social welfare costs.

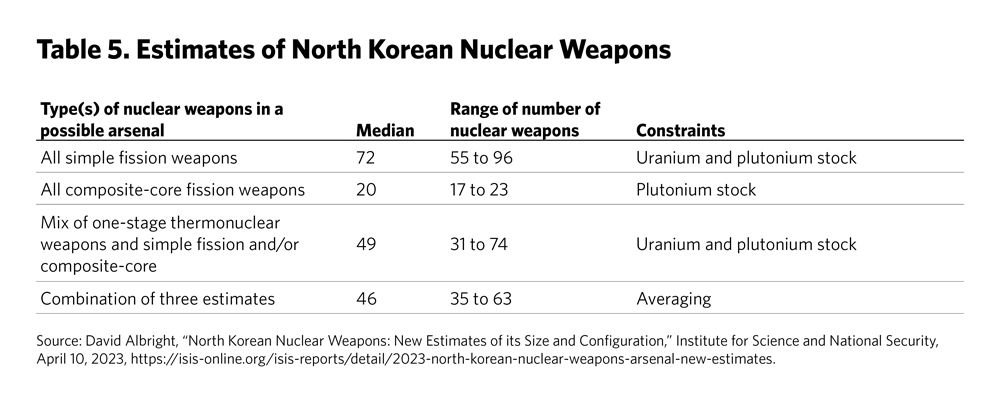

South Korean military leaders must also contend with how to address the security threat on the country’s northern border. For Kim and his regime, the centrality of nuclear weapons and WMDs cannot be overstated. Without them, he would not be able to outspend South Korea on increasingly sophisticated conventional military technologies, nor would he be able to ensure the survival of his regime. Despite the tanking of the North Korean economy and the worsening plight of average North Koreans, Kim will continue to develop nuclear weapons and maintain the 1.1 million-strong force structure of the Korean People’s Army for four key reasons.109

First, nuclear weapons shield North Korea from the full range of military power that the United States could bring to bear in the event of a major crisis or war on the Korean Peninsula (see table 5). Second, mobilizing the entire nation on a constant war footing is impossible without maintaining a very large conventional force and the world’s most brutal secret police network. Third, the North Korean economy cannot create enough jobs for North Korean youth, and long-term service in the armed forces enables Kim to keep the younger population in check. And fourth, modernizing and accelerating North Korea’s nuclear and WMD programs provides Kim with political leverage in managing crucial ties with China and Russia.

South Korea has adopted a three-pronged defense strategy known as the Three-Axis strategy in response to North Korea’s growing nuclear and WMD capabilities. This strategy is composed of the following elements: an operational plan (known as Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation) to incapacitate the North Korean leadership in the event of major conflict; a preemptive strike platform known as the Kill Chain strategy, designed to take out North Korea’s nuclear and WMD sites; and the Korea Air and Missile Defense System. The Yoon administration pledged to create a new strategic command to oversee this defense strategy, and in January 2023, the military launched the nuclear and WMD response headquarters as a precursor to setting up the strategic command.

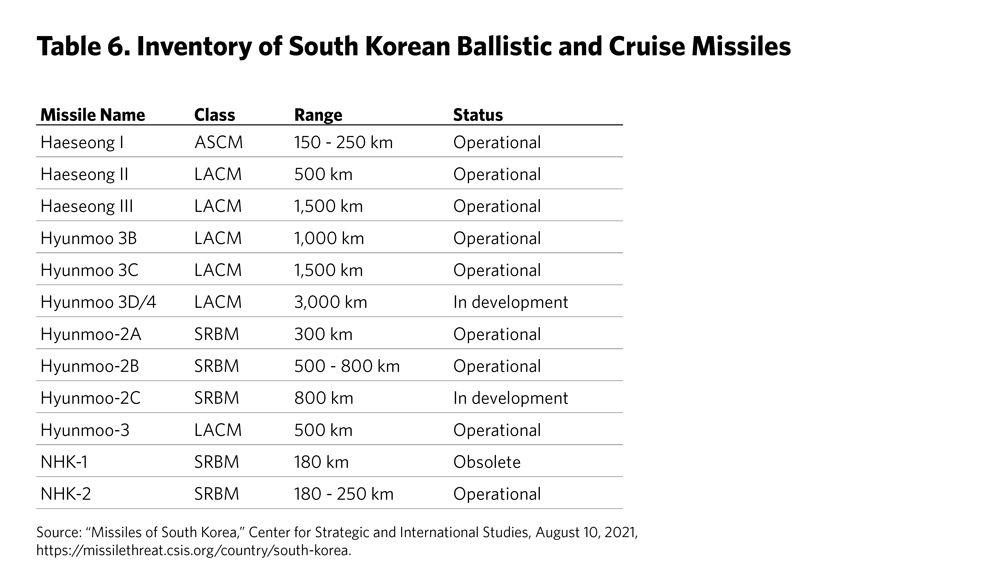

According to the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper, the strategic command is slated to assume multiple tasks. It “will integrate and operate a variety of capabilities, including not only the military’s precision and high-powered strike capabilities but also space cyber and electromagnetic capabilities, to carry out its mission of deterring North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats.”110 The command “will [also] oversee the coordination of various assets, such as the Hyunmoo series ballistic missiles, F-35A stealth fighters, Aegis destroyers, medium submarines equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and interception missiles like Cheongung and Patriot (PAC-3), for preemptive strikes against North Korea, missile defense, and massive retaliation forces” (see table 6).111

More broadly, in December 2023, the MND released its 2024–2028 Mid-Term Defense Plan, outlining a planned annual budget increase of 7 percent.112 Over the next five years, the government plans to spend a total of about $260 billion (or an average of $52 billion annually).113 Force modernization and maintenance costs will both increase. The plan stressed three key areas. The first is upgrading the Three-Axis system and related weapons platforms so that they can more effectively meet growing asymmetrical threats, especially in the face of North Korea’s sophisticated nuclear and WMD capabilities. The second is improving compensation packages and working conditions especially for NCOs and for officers at the front end of their careers. And the third task is implementing force structure reforms, since the military’s 500,000 manpower ceiling is no longer tenable; such reforms should ensure that key reorganized units have adequate personnel to support the strategic command and to operate the requisite advanced weapons systems.

As part of this force modernization plan, the MND has said that it plans to deploy the Cheongung-II midrange surface-to-air missile and the long-range Hyunmoo-V surface-to-air missile by 2028, with parallel development of improved midrange and long-range surface-to-air missiles.114 Long-range surface-to-air missiles are part of South Korea’s lower-tier missile system that targets terminal-phase upper- and lower-tier air defense systems. South Korea plans to build up to 120 KF-21 Borame 4.5-generation combat aircraft by 2032 and if the government decides to proceed with more advanced versions such as a 5G-variant of the KF-21, new variations could be built.115 While the KF-21 uses two General Electric engines, plans are under way to supply the next-generation KF-21s with engines built by Hanwha Aerospace by 2040.116

South Korea continues to maintain a nonnuclear posture and depends on U.S. extended deterrence, although opinion polls have shown rising public support for an indigenous nuclear program, as illustrated in figure 8 below. To be clear, Seoul is not on the verge of going nuclear, given the very high opportunity costs such a move would entail, such as a weakened alliance with the United States, international economic repercussions, growing military pressures from China and Russia, and the risk of triggering a nuclear domino effect in East Asia.

Nevertheless, as Seoul ponders the long-term future of U.S. extended deterrence—especially if Trump reclaims the White House in January 2025—the possibility of a gradual withdrawal of U.S. forces on the Korean Peninsula and a weakening of the U.S. nuclear umbrella cannot be ruled out. In addition, Seoul and Washington are slated to negotiate in 2024 on a new multiyear special measures agreement on defense cost sharing, and if Trump returns to office, he may well push for a major hike in South Korea’s annual contributions of around $1 billion.117 During his first term, Trump called on Seoul to increase its annual defense cost-sharing support from approximately $1 billion to $5 billion, though negotiations ended with Seoul agreeing to increase its contribution by 13.9 percent, “the biggest annual rise in nearly two decades.”118

Talks are under way between the Yoon and Biden administrations to reach a new agreement to ensure a smooth transition even if Trump wins a second term in November 2024. As a Reuters article put it, “from 2016 through 2019, the U.S. Department of Defense spent roughly $13.4 billion in South Korea for military salaries, construct facilities, and perform maintenance, while South Korea provided $5.8 billion to support the U.S. presence.”119

As noted above, one of the main concerns over the long-term prospects for South Korean military power is the growing shortage of troops due to the country’s rapidly falling birth rate. But despite the country’s declining military manpower, South Korea’s defense industry has continued to develop a range of weapons systems and ISR capabilities to respond more effectively to growing threats from North Korea and, increasingly, from China. One consequence of maintaining an advanced defense industrial base has been the growing attractiveness of South Korean weapons, especially when many NATO member states, for example, weren’t able to rapidly resupply key weapons because existing supplies were shipped to Ukraine following Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.

Although South Korea’s arms sales began to rise starting in the 2010s, a big boost came with the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, when South Korea rapidly sent tanks, artillery, and even combat aircraft to several NATO states, since many of them couldn’t fulfill orders to resupply the initial batch of weapons that had been sent to Ukraine. In 2023, South Korea’s arms exports were worth nearly $14 billion, after reaching a high of $17.3 billion in 2022, including huge contracts with Poland.120 According to 2023 data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute on arms transfers, South Korea ranked number ten in the world in arms exports (see table 7).

There are five reasons behind South Korea’s surging arms exports. First, unlike many of the countries in NATO, South Korea did not mothball or downsize its defense industries after the end of the Cold War with German unification in 1990 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Countries such as the Czech Republic were an exception, since they did not suspend the sizable defense industries that had existed throughout the Soviet era. As Ukrainian forces have begun to run out of artillery shells, Czech companies have evaded bureaucratic hurdles and have provided a tranche of 300,000 shells.121