The rising pace and cost of disasters is cause for alarm, both because of the likelihood of major disruption in so many people’s lives, and because of the potential for systemic failures in the housing and insurance markets that could lead to wider, global economic shocks.

Source: Getty

Adaptation Through Shock

Climate shocks, such as recent, devastating Hurricanes Helene and Milton, open windows when the disaster recovery system can encourage and support adaptation to new climate realities.

Introduction

We know the world will look dramatically different one hundred years from now: It’ll be hotter, the oceans will be higher, and the most productive farmlands will be further north. Many of the places where we live won’t be recognizable or even exist, and hundreds of millions of people will have moved. Much of this change will be wrought by disaster: The sudden shock of a major water, fire, or wind event will be the tipping point pushing people to relocate.

There’s not a lot of good news about disasters. Those of us who read and write about the effects of a changing climate are raging and grief-filled for what’s being lost. But the moment also demands imagination about how we can create more just societies within the limitations of the dramatically changed world we know we’ll face. Disasters are moments when change happens in communities: Resources flow, and decisions, big and small, are made to rebuild, to elevate, to harden, or to say goodbye. Disasters push people and communities to ask what their future will look like as the policy landscape changes.

Three aspects of system flexibility in the aftermath of disasters make them unique moments for advancing potentially positive adaptive change: individual and collective willingness to envision new ways to live, large increases in funding from public and private sources, and emergency powers the government grants itself that increase flexibility across a range of functions.

To drive adaptation toward a more resilient future, expanded policy imagination is needed to: prioritize people over property in disaster-recovery programs, develop forward-looking supportive relocation programs, use data to support people wherever they are after a disaster, and create incentives to develop affordable housing in destination communities where disasters will drive people in our new climate reality.

Three Dimensions of System Flexibility After Disasters

No matter if it’s a sudden fire, a dreaded hurricane, or a flash flood, our image and experience of disasters is one of loss and chaos. What’s less visible is that disasters also prompt valuable flexibility across multiple dimensions: individual and collective decisionmaking, financial mechanisms, and governance authorities.

First, the period after a disaster is often a time of reflection and acceleration of individual and collective decisionmaking about how and where to live. As one resident of Montpelier, Vermont, told the podcast 99% Invisible after the 2023 floods in the city, “If it floods again, I’m just going to get in my car with my dog and my cat, my wife, and just keep going.”

In normal circumstances, most people who live in areas vulnerable to the effects of climate change don’t move, despite the risk. As Caroline Zickgraf concludes in her work on global migration, “the vast majority of people living in places highly vulnerable to climate change do not migrate.” For many, lack of resources to migrate is certainly a driving factor in the decision to stay, but there are other reasons to stay. People have established lives in these places—schools, jobs, family connections, friends—and are not eager to upend everything, even as obvious threats creep closer. As Helen Adams notes in her research on the complexities of the factors that shape climate migration, “while place attachment and social capital are known to increase capacity to adapt to incremental change, they can act as a barrier to transformational change, for example, through migration.”

While the pre-disaster threat of climate risk alone does not motivate decisions to migrate, many people do decide to move following a disaster, inspired, at least in part, by a desire to live in lower-risk areas. In a 2022 study of the impact of hurricanes, coastal storms, and floods on household migration decisions in the United States, Tamara Sheldon and Crystal Zhan found that people are more likely to move in response to highly destructive disasters, and that their ability to do so is influenced by the availability of financial support. They conclude that “households may use migration as an approach to adapt to environmental risks and protect themselves from future disasters” because migrating households “show a stronger preference for destinations with fewer past disasters than the origin when moving,” whether locally or across long distances.

While most cases of post-disaster migration are relatively small-scale, some involve mass movements, such as the thousands of people who arrived in Houston from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (see figure 1) or the 300,000 Puerto Ricans who relocated to the mainland United States after Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Emerging research shows that disasters have a time-limited effect on psychological and relational functioning. A study of survivors of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey found that newly married couples “appear to grow closer in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster but then revert to their prehurricane levels of functioning as the recovery period continues.” This reinforces the notion that post-disaster personal flexibility is finite and that people eventually return to pre-disaster patterns.

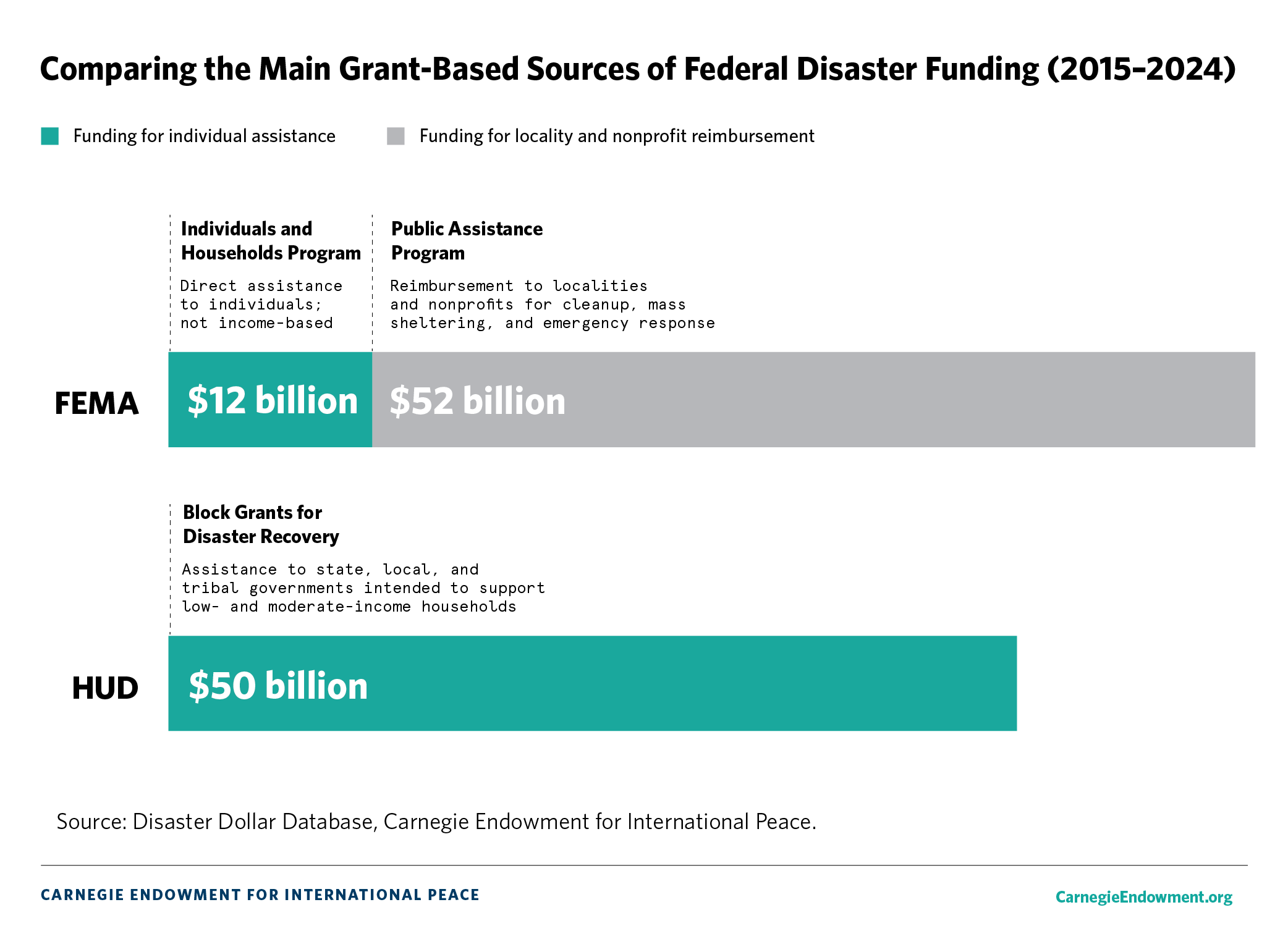

The second area of flexibility in disaster response is characterized by flexibility and expansion in the financial mechanisms for recovery. In the United States, the federal government allocates large amounts of funding via grants to individuals and jurisdictions to that end. Carnegie’s Disaster Dollar Database records $114 billion in spending since 2015 in response to the largest disasters in the United States (see figure 2).

Other countries facing high levels of disaster risk also have frameworks for allocating resources to disaster relief and reconstruction. In India, the offices of the prime minister and of the chief ministers of at least ten states operate Calamity Relief Funds that direct public and corporate donations to disaster-recovery efforts like homebuilding, compensating loss of life, and land rehabilitation. In flood-prone Bangladesh, UN agencies have piloted anticipatory direct cash transfers to flood-affected families that reduce economic hardship and protect child nutrition. And in Brazil, the government has sought to provide rapid responses to disasters by issuing Civil Defense Payment Cards (CPDC) to municipalities. When a municipality declares a disaster, the National Secretariat of Civil Defense activates the municipality’s CPDC account, dramatically reducing the time it takes to start recovery efforts.

In addition, large amounts of charitable giving often follow disasters. In the United States, research by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy found that disaster-related charitable giving amounted to about $3 billion, or 2 percent of all philanthropic funds disbursed in 2021 by foundations, corporations, and public charities. Approximately 30 percent of households made a disaster-related donation in 2017 and 2018. Unlike the lengthier process for releasing federal funds after a disaster, philanthropic spending tends to arrive earlier in the disaster life cycle: Almost half of the funds are usually spent before long-term recovery has begun.

Third, disasters result in emergency governance powers for law enforcement, taxation, grantmaking, and loan repayment and obligations. For example, during the 2019–2020 bushfire season in Australia, the state of Victoria invoked a “state of disaster” for ten days in January 2020 that invested the state’s police minister with the power to coordinate all government agencies and resources, including the suspension of legislation. In India, the Disaster Management Act allows disaster authorities at the national, state, and local levels to requisition any needed resources, facilities, or vehicles to aid in disaster-relief efforts (with compensation to be provided at a later date). A similar rule applies under Mozambique’s Law for the Management and Reduction of the Risk of Disasters.

Across Australia, people living in recognized disaster-affected areas are entitled to pauses or restructuring of their debt obligations. Similarly, in Japan, a state of emergency can result in the deferral of monetary debts, as well as in tax reductions, travel restrictions, rationing, and price fixing. During this year’s disastrous floods in the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, the national government suspended the state’s debt, organized tax relief for residents, and offered assistance in debt negotiations to businesses in the state.

In the United States, the Stafford Act is one of several laws that define federal emergency powers. It applies specifically to disasters and lays out the framework for major federal disaster assistance “to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damage, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby.” For major disasters, these powers range from the suspension of vehicle weight requirements to flexibility in how many military reservists can be called up to which agricultural reserves can be used or sold. The National Response Framework from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) further defines both the emergency operations protocols across a range of federal agencies and the agencies’ interactions with state, local, and tribal governments, in addition to nonprofits and the private sector. The guiding principle of the framework is that operational capabilities must be scalable, flexible, and adaptable.

This is not to say that even the most generous and flexible disaster-recovery systems are sufficient to meet the situation we face globally. But these three aspects of flexibility—personal, financial, and governmental—can combine to help create an environment where people and communities are empowered to make choices around mobility and adaptation that might not have been available prior to a disaster.

A Disaster-Recovery Framework for the Future

A disaster-recovery framework that looks to the past and focuses on rebuilding in vulnerable places isn’t adequate for the climate we already live in, much less the climate of the very near future. However, a disaster policy framework that is well funded and has flexible governing authorities could be reimagined for positive adaptation. Below, we examine potential policy changes to that end, with a focus on the U.S. experience. These adaptations consider disaster-impacted communities as well as destination communities to which people will migrate to escape acute climate risks.

1. Prioritize people instead of property with disaster assistance that people can bring with them if they choose to leave affected areas.

The prime driver of current disaster policy (and many disaster recovery systems) in the United States is the recovery of the jurisdiction and the tax base of the community where the disaster occurred. The system is organized around property: Funds flow from the federal government as well as from insurance companies and philanthropic organizations into the recovery of homes, businesses, and infrastructure in disaster-impacted jurisdictions. Insurance money is often tied to mortgage companies, which seek to restore the resale value of impacted properties. In this framework, the measure of success is the restoration of buildings, regardless of who occupies them.

But given rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, and growing fire risk (among other hazards), this property-focused framework is increasingly untenable. Not all places will be able to recover from the disasters of the coming century, and it’s time to shift our focus to the recovery of the people in affected communities, measuring the success of disaster response by the outcomes for people rather than for residential or commercial units. As Abrahm Lustgarten argues in On The Move, “The places around the world we think we can live now will not be the same as the places where we will be able to live in the future.”

For example, many oceanfront towns in New Jersey were redeveloped in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, meaning that communities that had been made up of low-cost rentals and small, turn-of-the-century bungalows were rebuilt as communities of large, modern McMansions. These new, higher-value homes created additional revenues for local governments while thousands of lower-income households were displaced.

As the New York Times put it, “Almost five years after Sandy wreaked havoc, much of the fear in this part of the Jersey Shore has dissipated as wealthy clientele build significantly larger homes along the coast. Combined with the millions of public dollars spent on new boardwalks, parks, roads and beaches, these once sleepy towns are seeing their profiles fully reinvented.” In a place-based disaster recovery model, this is seen as a success: These towns fully recovered. However, many of their former residents did not.

A simple shift in policy among governments, insurance companies, banks, and nonprofits could address this challenge. Resources should follow people, allowing them to rebuild their lives in a new place rather than only in their old place.

This recommendation has particular resonance in the United States, where the federal government operates long-standing, property-based disaster recovery programs. In a reimagined framework, people would get assistance from FEMA to move to a new home in another community, just as they would to rebuild their damaged property. Post-disaster, government-backed grants and loans could be used for buying a new home and not just repairs on the old.

Insurance companies and banks could allow or even incentivize homeowners to spend their settlements on lower-risk properties, regardless of location. Disaster recovery nonprofits could assist households choosing to relocate at least to the same level as they would those choosing to stay. Disaster philanthropy, in particular, could ensure that funding is tied to the recovery of survivors, not properties, and it could incentivize creative solutions to support survivors as they plan their next steps and as they rebuild new lives, no matter where they choose to live.

This strategy depends on the availability and reliability of future-looking risk-based maps, which is no small task. Accurate risk-mapping would, for example, help clarify that in some cases moving across town can be as much of a resilience strategy as moving much further away, at least in the medium term. A shift of focus to people would allow funds to be spent in locations where risk is lower and preserve the well-being of individuals and communities for the long haul.

2. Develop forward-looking, supportive relocation programs.

In the United States, relocating people out of harm’s way operates between two extremes: massively expensive buyout programs or no support at all. This isn’t viable. In communities that are extremely vulnerable to climate change, the U.S. federal government, in partnership with state and local governments and nonprofits, has piloted whole-of-community relocations in Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana and Newtok in Alaska as well as smaller neighborhood buyouts across the country. Beyond massive undertakings such as these, the major intervention available to people who own property in risky areas is locally administered home-buyout programs that are funded through a combination of federal and local grants, and sometimes philanthropy. Buyout programs are designed to compensate owners and turn their former homes into green spaces, but they’re often fraught with issues related to the pain and cost of moving people. Even assuming it’s possible to perfect buyout programs, there’s simply no way to scale them up to fully compensate the millions of people whose homes will become uninhabitable in the coming decades.

At the other end of the extreme is leaving people on their own. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has been warning of a looming financial crisis resulting from the failure of the insurance, mortgage, and municipal bond markets in large parts of the coastal United States. In such a scenario, people will be forced to abandon risky property without support from governmental or financial institutions. An adaptive disaster recovery strategy must include other forms of support than highly expensive buyouts or the chaos of leaving people totally on their own.

To meet the challenges ahead, significantly more attention, imagination, and coordination is needed to incentivize and to support people who need (and choose) to move out of harm’s way. The solutions that will be required must leverage government spending and regulation, private-sector financing mechanisms, and charitable programs in communities most affected by climate change and in those that will be more resilient in the new climate.

Refugee resettlement in the United States provides a useful parallel for a climate adaptive strategy: Resettled refugees receive a mix of support from government agencies, international organizations, and local charities for relocation, temporary housing, and other financial support, as well as social support to encourage community integration. These are time-limited efforts that leverage multiple systems to set up people in a new life. Faith-based and community groups have long been leaders in this sector, and they have valuable experience and skills to apply to the growing need for disaster-recovery in the coming years, particularly when it comes to ensuring local community engagement and social integration.

3. Use data and existing programs to support survivors beyond the geographic limits of the disaster-impacted community.

The current disaster recovery system directs the majority of resources to survivors in or near the impacted location, regardless of where they are actually located. In the United States, soon after a disaster, various organizations work with FEMA and state authorities to open Multi-Area Resource Centers (MARCs) to serve survivors. These are only located in or near the impacted communities. Official MARC planning guidance tells planners to identify “potential facilities in close proximity to the impacted area but located in safe areas,” directing them to prioritize proximity to damaged property, not the people who need the support. This creates incentives for people to return to their property instead of seeking stability elsewhere and provides greater resources to those close to the disaster-affected area.

At least since the earthquake in Haiti in 2011, researchers have been able to use data from mobile phones and apps to quickly discern where people migrate after a disaster. In an analysis of post-disaster migration patterns in Haiti, Japan, and Puerto Rico using mobile phone data, a team of researchers found that there was great variation in how far and for how long people stayed away from their home communities. Emergency planners could use such data to determine where survivors are going in the days immediately following a disaster to better plan response activities.

In refugee settlement cases, communities must have support to successfully integrate newly arrived people. For example, in Springfield, Ohio, there was an absence of support for increases in affordable housing to accompany Haitian migrants coming to the city for jobs, so housing prices went up significantly, and there’s been a fierce and politicized community backlash. In a disaster context, New Orleans residents who permanently resettled in Houston after Hurricane Katrina were perceived as a drain on resources, were blamed unfairly for crime, and continue to face discrimination in hiring and housing.

FEMA’s Public Assistance (PA) program could be deployed beyond immediate disaster zones to provide the necessary community-integration support. Similar to how school funding is based on student attendance, it could track where survivors have migrated and make public assistance funding available to communities receiving disaster survivors above a certain threshold.

For example, given that at least 4 percent of Puerto Ricans relocated off the island following Hurricane Maria, a similar percentage of PA allocation could have been directed to communities receiving them. This would’ve directed $1.36 billion from PA (of the more than $19 billion Puerto Rico received) to help destination communities build the roads, schools, and other infrastructure necessary to accommodate new arrivals.

FEMA used PA in this way in the aftermath of the 2011 Haiti earthquake and to resettle Afghan refugees across the United States. The assistance covered by the program’s mass-care support function—food, shelter, distribution of key supplies, direct emergency aid—would be only temporary in destination communities, but they’re key interventions as impacted people weigh their next steps in these first few critical weeks after a disaster. Communities in disaster-impacted areas have used PA to fund school construction, rebuild courthouses, and repair infrastructure like roads and water-treatment plants, resources that would be enormously useful in receiving communities as well. A mass-care system funded and supported by FEMA in destination and impacted communities would even the playing field by ensuring that the same resources are available in both, rather than pushing people back to impacted and often riskier locations in order to receive greater benefits.

Not only would this approach make fiscal sense and help address resource shortages that might lead to conflict between longtime residents and newcomers, but it would also create incentives for cities to receive climate migrants, and the quality of a destination community’s welcome would become a comparative advantage.

4. Create incentives to develop affordable housing in destination communities.

For the most part, the current policy frameworks for disaster recovery are backward-looking and reactive: Funding flows after the disaster to rebuild property as it was before the disaster. A policy framework for the future would anticipate that dramatically more affordable housing has to be built in less risky places, often far from where disasters are occurring. In the United States, the federal government already spends significant resources on affordable housing as part of its disaster-recovery strategy, primarily through post-disaster emergency grants by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and its Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program. HUD has allocated $50 billion through these grants to states and local jurisdictions since 2015.

If disasters are part of the way that people and communities move into adaptation, this funding should be more predictable and more flexible. In the current framework, CDBG-DR is only a program for emergency grants to places after they are hit by disasters. Some disaster-prone jurisdictions have benefited significantly from this: 70 percent of the $50 billion in CDBG-DR grants since 2015 has gone to four places: Puerto Rico ($18.7 billion), Texas ($11 billion), Louisiana ($6.1 billion), and Florida ($5.3 billion). There is no similar program for jurisdictions whose population is increasing as a result of their hospitable climate and where much more affordable housing will be needed.

While there’s recognition in the United States that more affordable and resilient housing is a necessity for the future, there is no climate-sensitive geographic lens for where that housing will be built. In June, the Joe Biden administration announced rule changes to encourage the development of affordable housing, and as a presidential candidate, Vice President Kamala Harris has called for incentives to develop 3 million additional units for sale to first-time homebuyers. While the rule changes and Harris’s campaign platform broadly endorse green building standards and climate resilience, they’re not climate-sensitive in terms of where affordable housing development will be prioritized. Building hundreds of thousands of units in locations that will be difficult, if not impossible, to live in within decades isn’t smart policy, even if those buildings are made from green materials, elevated out of the flood plain, and resilient to high winds.

Conclusion

Those of us who study and write about the changing climate—and really anyone who’s living in the current environment or thinking about our children’s futures—are rightfully afraid of the future that scientists have explained to us: communities destroyed by rising sea levels, unbearable heat and drought, and countless and intense disasters. It’s terrifying. But it’s also a moment for imagination, possibility, and action. There’re things we can do right now, using dollars we already spend, to begin to make a significant difference in softening the blow of the coming climate catastrophe. But many of the possible policy shifts will be necessary to bring an adaptation lens to a disaster recovery framework.

A unique window opens after disasters because of time-bound flexibility in the psychological, financial, and governance dimensions. People, as well as financial and governance frameworks, are more flexible in post-disaster moments. Even in the face of traumatic loss from disasters, we should be thinking about these moments as a time to allow people to move toward adaptation by using resources that already are flowing for recovery as well as those that are new or redeployed.

Positioning disasters as part of an adaptation strategy opens up avenues for action. Imagine a world in which, during the unique window after a disaster, people could take resources with them to a new, resilient home, instead having to rebuild in place. Data could guide where to provide supportive resources in the critical weeks after a disaster to the places where people are actually located. Decisions about where to live could be guided by flexible funding from the government, financial institutions, and charitable organizations that prioritize future resilience. People could be supported not only through expensive buyouts but also through coordinated public and private programs that support their integration wherever they go. Housing policy could be guided by future population patterns instead of those of the unsustainable present.

Fear and imagination must live side by side as we think about the climate of the future. Rebecca Solnit describes in A Paradise Built in Hell how disasters allow people to reconnect with the “purpose and closeness” that is so fleetingly available in contemporary society. These moments are ripe for action as individuals and communities take the small and big steps to create the more just world that we fear will be impossible but we know we must work for.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Federal Accountability and the Power of the States in a Changing AmericaCommentary

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

- Trump Wants “Peace Through Construction.” There’s One Place It Could Actually Work.Commentary

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan

- Taking the Pulse: Is It Time for Europe to Reengage With Belarus?Commentary

In return for a trade deal and the release of political prisoners, the United States has lifted sanctions on Belarus, breaking the previous Western policy consensus. Should Europeans follow suit, using their leverage to extract concessions from Lukashenko, or continue to isolate a key Kremlin ally?

Thomas de Waal, ed.

- Can Venezuela Move From Economic Stabilization to a Democratic Transition?Commentary

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy