From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

Source: Getty

Many of the countries with globally significant mineral resources—which the United States and its allies will depend on to diversify the clean energy supply chain—are deeply energy insecure.

Facing historic drought conditions in August 2024, the Zambian utility announced it would likely need to shut off electricity production at the Kariba South hydropower plant, which normally generates more than half the country’s power. Zambia’s electricity sector has struggled with low water levels for years, imposing rolling blackouts on residential and commercial customers. These outages—lasting at times up to twenty-one hours per day—not only devastate local businesses, hospitals, and agriculture but increasingly also pose a significant challenge to global energy supply chains.

As one of the world’s largest copper producers, Zambia accounts for about 4 percent of global copper supply. The country has ambitious plans to scale up its output, with major players such as Rio Tinto and First Quantum ramping up exploration budgets. But the mining sector’s energy intensity makes it highly vulnerable to power disruptions, which can halt operations, drive up costs, and threaten profitability. In response to the recent outages, major mining companies have scrambled to find new ways to procure electricity, including importing it directly from South Africa at significant additional cost. And when Zambia’s mining sector struggles, so does its broader economy: the industry accounts for about 12 percent of the country’s GDP and 70 percent of its foreign exchange earnings.

Zambia is not an isolated case. Many of the countries with globally significant mineral resources—the countries upon which the United States and its allies will depend to solidify their own energy security by diversifying the clean energy supply chain—are deeply energy insecure. It is a tragic irony—and a historic opportunity.

If the United States wants to ensure that energy supply chains are resilient and diversified away from overwhelming dependence on China, it will have to depend on its allies—and present them with an offer of true partnership for mutual benefit. Africa has twenty mineral-producing countries. As global demand for minerals critical to the energy transition accelerates, these countries are understandably keen not only to boost raw material production but also to do so in a way that drives broader social benefit, economic development, and job creation. Countries including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have published country-level strategies linking minerals to development. The African Union’s Africa Mining Vision and the United Nations’ new guidance for energy transition minerals both emphasize value addition and economic diversification in mineral-producing countries. The United States committed to supporting this vision by signing a memorandum of understanding with Zambia and the DRC in 2023 to help build an electric value supply chain “from the mine to the assembly line.”

Nearly all mineral-rich lower-income countries share a significant hurdle to realizing such ambitions: an unreliable power supply and often a complete lack of functional grid access in rural and remote areas, where mineral resources are often located. The lack of stable grid power forces firms to secure their own private generation—most often through diesel generators—increasing operating costs dramatically, by about 33 percent for the average African commercial firm. In Zambia, ensuring 24-7 electricity with a private back-up can cost roughly three times more than the industrial grid tariff, making it nearly impossible for an energy-poor country to develop globally competitive manufacturing or industrialization, no matter its resource wealth.

As the Zambia case illustrates, building out global clean energy supply chains will require investing in the local energy systems of developing economies. This presents an opportunity to advance multiple U.S. national security goals in tandem: scaling up production of the minerals the world needs in the twenty-first century; diversifying critical components of clean energy manufacturing away from China and Russia; and deepening partnerships with allies that desperately need more energy to power stability, prosperity, and growth.

There are inherent synergies that make the mining and power sectors compatible, creating opportunities for smart, effective investment. Mines and mineral processing operations need abundant, reliable, affordable power supply. They also represent high-volume, reliable customers for African power utilities that currently face major financial constraints and need industrial consumers to anchor their broader operations. Globally, mining companies are already developing significant amounts of clean power—both directly on-site and elsewhere—and crafting new procurement arrangements that can benefit the rest of the power system.

U.S. policymakers from both political parties have repeatedly confirmed the United States’ national security interest in diversifying the global clean energy supply chain and, through initiatives like Power Africa, in catalyzing investment in these countries’ energy systems. Recognizing the inherent linkages between these two goals is fundamental to achieving either one. To enable mining, processing, and manufacturing in low-income economies, the United States needs to design and follow through on country-specific energy security investments.

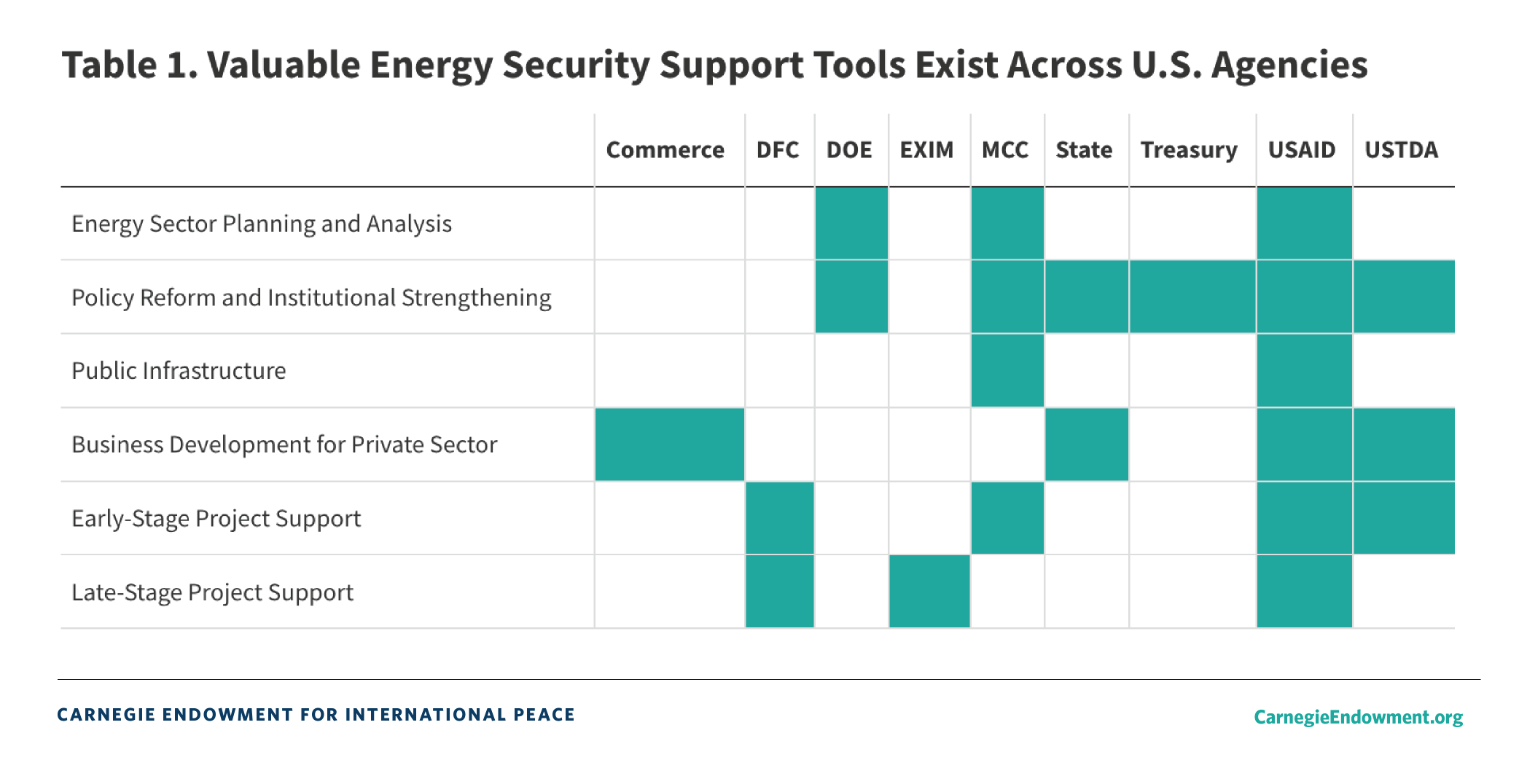

However, U.S. capacity to deliver that type of country-specific, holistic support is currently hampered by four major limitations. First, powerful tools, including loans, insurance, early-stage project development assistance, commercial advocacy, and policy expertise, are spread across at least ten different agencies, requiring potential partners and investors to exert Herculean efforts to navigate the bureaucracy (see table 1).

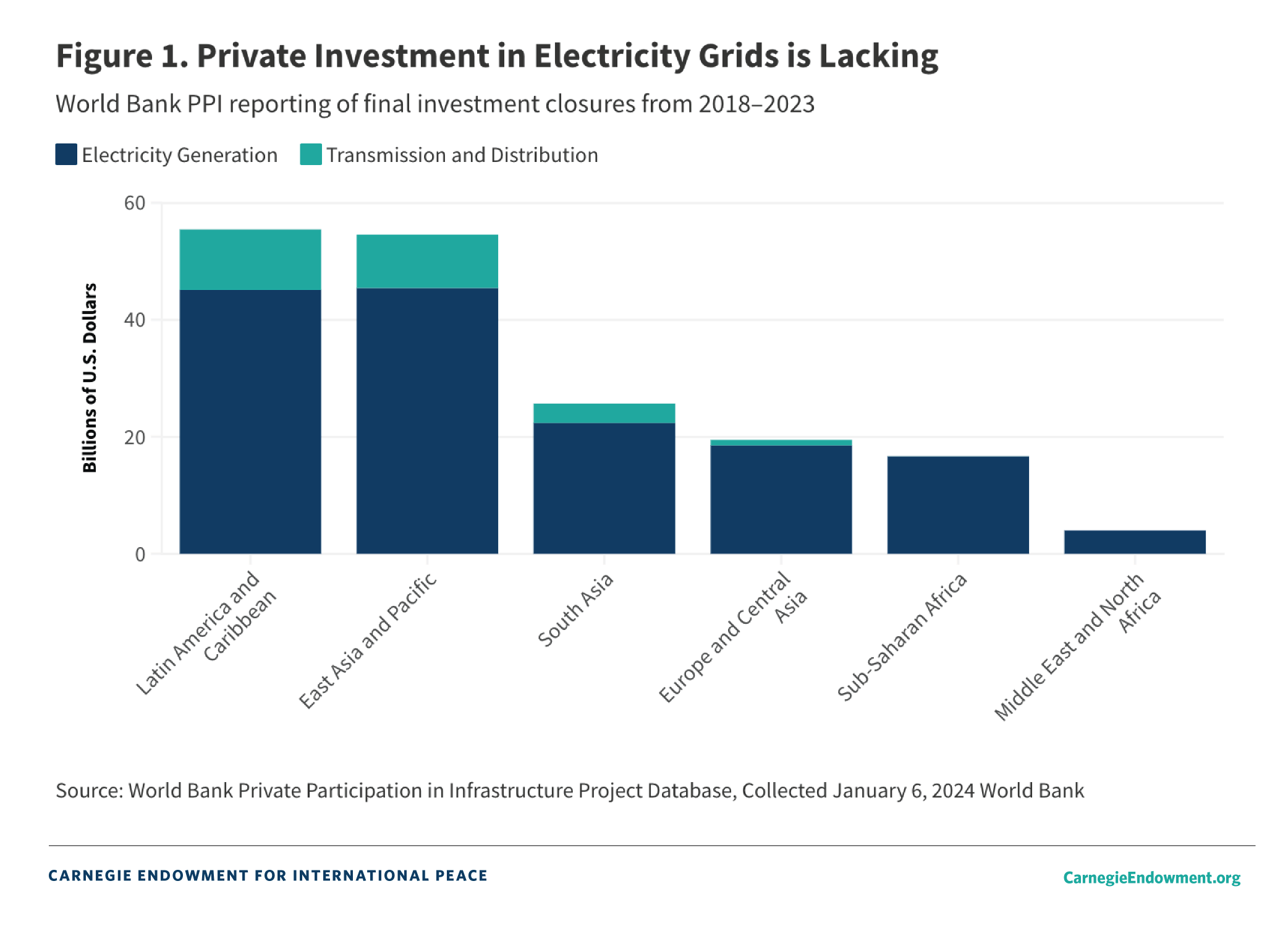

Second, while the United States has $60 billion in debt capital available to support late-stage transactions through the Development Finance Corporation, the pipeline of investment-ready energy deals in most lower-income markets is exceedingly thin, requiring much more support for the riskier stages of early-stage project development. Third, the United States has few tools to support the often publicly owned enabling infrastructure, like grid systems, that will be crucial in getting energy to mines and other consumers (see figure 1). Finally, United States development finance tends to approach overseas energy sectors as a series of disjointed, project-specific lending opportunities rather than what they really are: complex systems that require a smart mix of loans, policy reforms, public infrastructure, and technological innovation across many different kinds of assets and institutions.

The United States needs a mechanism to provide holistic support for countries whose energy security is key to its own. Energy Security Compacts, a proposal put forward by the Energy for Growth Hub,lays out a way to build and implement packages of holistic support for countries. By learning from the success of U.S.-led initiatives like the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), Power Africa, and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure, Energy Security Compacts would give the United States a powerful mechanism for crafting holistic packages of coinvestment in energy solutions. The proposal would give MCC—which enjoys broad bipartisan support, a well-earned reputation as the world’s most transparent bilateral international development agency, and a proven track record of transforming power sectors—the mandate to partner with countries to design multiyear compacts to tackle the most binding local constraints to energy security and, crucially, to coordinate other U.S. agencies in contributing their own tools and resources.

This approach addresses the major limitations in existing U.S. assistance. MCC’s compact methodology approaches the energy sector not as a collection of stand-alone projects to be financed, but as a system, identifying with the partner country through a rigorous data-driven methodology the most impactful investments across generation, transmission, distribution, and policy. It provides multiyear support—which is crucial when the goal is developing large-scale infrastructure. And it has strong accountability mechanisms to ensure that partners follow through on promised reforms, and that programs deliver results. MCC alone among U.S. development agencies has the ability to provide significant capital for extension and rehabilitation of public grid systems. By enabling MCC to coordinate compact contributions from other U.S. agencies, like the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC)—just as USAID did under Power Africa—this model would enable greater efficiency and leverage.

In a country like Zambia, such a compact could include harnessing existing diagnostic tools from MCC and Department of Energy (DOE) national labs to assess the country’s economic constraints and energy security needs; MCC capital to strengthen the grid, increasing reliability to mines, processing facilities, and other customers; direct financing and other support from DFC and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) to help mining companies invest in their energy needs; and technical assistance from USAID to strengthen mining operations and standards. MCC’s authority to implement regional compacts involving more than one country could also be used to support mineral investments and energy security partnerships that reflect the facts that mineral resources often cross international borders and that the continent as a whole is moving toward tighter regional integration.

In today’s rapidly evolving global landscape, the United States cannot achieve energy security in isolation. U.S. success is intrinsically linked to that of resource-rich, energy-poor countries like Zambia, which have not been historically considered central to U.S. security or economic well-being, but are now critical to diversifying and expanding clean energy supply chains.

Recognizing and investing in the energy security of these nations is not a gauzy development ideal—it is a national security imperative. It will require investments in mutual prosperity, high standards, and clean energy systems to both power the world and enable local communities to grow and thrive.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

From Sudan to Ukraine, UAVs have upended warfighting tactics and become one of the most destructive weapons of conflict.

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

And how they can respond.

Sophia Besch, Steve Feldstein, Stewart Patrick, …

They cannot return to the comforts of asymmetric reliance, dressed up as partnership.

Sophia Besch

As European leadership prepares for the sixteenth EU-India Summit, both sides must reckon with trade-offs in order to secure a mutually beneficial Free Trade Agreement.

Dinakar Peri

Baku may allow radical nationalists to publicly discuss “reunification” with Azeri Iranians, but the president and key officials prefer not to comment publicly on the protests in Iran.

Bashir Kitachaev