Christopher Shell

Source: Getty

Kamala Harris’s Racial Identity and the Black Electorate

Harris's opponents repeatedly attacked her race. A survey of Black voters shows those attacks had an unintended effect.

Introduction

Kamala Harris’s elevation to the top of the Democratic presidential ticket in July 2024 positioned her to become the second Black and first woman U.S. president. Her candidacy was a watershed moment widely recognized by the media, even as her campaign shied away from identity politics.

As Donald Trump, now president, adjusted to his new opponent, he publicly attacked Harris’s racial identity, repeatedly claiming that she “happened to turn Black”—a reference to her mixed-race heritage as a half Black (Jamaican) and half South Asian (Indian) person. These attacks, along with others, came at a time when Black voter enthusiasm for Harris’s candidacy was lower than the overwhelming support for former president Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

Given the critical role racial identity has played in mobilizing Black voters in past elections—and its significance in this one—our survey, conducted prior to the election in early October 2024, aimed to assess the extent to which attacks on Harris’s racial identity, by Trump and others, were influencing Black voter enthusiasm for her candidacy.

Among 1,100 Black registered voters, we found that public attacks on the authenticity of Harris’s racial identity had minimal overall impact on support for her candidacy. In fact, respondents who were aware of the attacks questioning the authenticity of her Blackness were more inclined to support her candidacy. Race-based identity attacks only resonated with a small group of respondents who already had a predisposition to vote against her.

The full results of the survey conducted by the Carnegie Endowment’s American Statecraft Program and YouGov are available here.

Purpose of the Study

In the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Black voter turnout and support for the Democratic Party reached historic levels with Barack Obama, a Black candidate, leading the ticket. In 2008, Black voter turnout increased by 5 percent compared to 2004, with Obama capturing a whopping 95 percent of that Black vote. Black voting behavior in this historic election aligns with research showing that a political candidate’s race—specifically the ability to establish a strong bond with the Black electorate based on shared racial identity—plays a critical role in mobilizing support.

Since the 95 percent peak, the share of Black Americans voting for the Democratic Party, at the presidential level, has declined. For instance, research presented in a recent New York Times article shows that 92 percent of Black voters supported the Democratic candidate in 2016, and 90 percent did so in 2020. Support from African Americans for the Democratic Party is clearly eroding.

In the 2024 presidential election, AP VoteCast estimates that Harris secured 83 percent of the Black vote, while 16 percent went to Trump. Although this represents a decline from Obama’s overwhelming support in 2008, Black voters remained the racial group most supportive of Harris. Nonetheless, many strategists, including Obama, expressed concern that Harris had not achieved the level of enthusiasm or support seen during both of Obama’s campaigns.

There are several potential explanations for this decline. These include perceptions that the Democratic Party has not fully delivered on police reform, affordable housing, or closing the racial wealth gap, as well as dissatisfaction with the United States’s involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Gaza conflict. We focused on understanding how attacks on the authenticity of Harris’s racial identity may have played a role.

Trump accused Harris of “wanting to be known as Black” during a July 2024 conversation between Trump and members of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) and at the presidential debate in September 2024. However, this critique was not limited to her political opponents; some Black celebrities (such as Janet Jackson) and Black conservative commentators (such as Candace Owens) have publicly questioned the authenticity of Harris’s Blackness. Ideas like this have taken root in the collective consciousness of Black Americans. For instance, a pre-election focus group of Black men revealed that some Black Americans believed that Kamala Harris was not Black and was embracing that racial identity to win over Black voters. These attempts by Trump and others to question the authenticity of Harris’s Black identity can be seen as an attempt to diminish the Black electorate’s attraction to her candidacy.

Furthermore, since Obama’s presidency, there has been an increase in grassroots Black political movements that distinguish between generational Black Americans and recent Black immigrants. They assert that leaders like Obama and Harris—both children of Black immigrants—cannot fully represent the interests of generational Black Americans.1

Although questioning a candidate’s racial identity is not new—Alan Keyes similarly questioned Obama’s identity during the 2004 Illinois Senate race—Harris’s experience is unique. Unlike Keyes’s attacks, which predated the era of social media, discussions about Harris’s racial identity were amplified by platforms that allowed these conversations to reach a wider audience. Given the prominence of these debates during the 2024 election, and the prospect of their being used in future elections, this survey sought to assess the extent to which these attacks influenced Black voter support for Harris.

Results

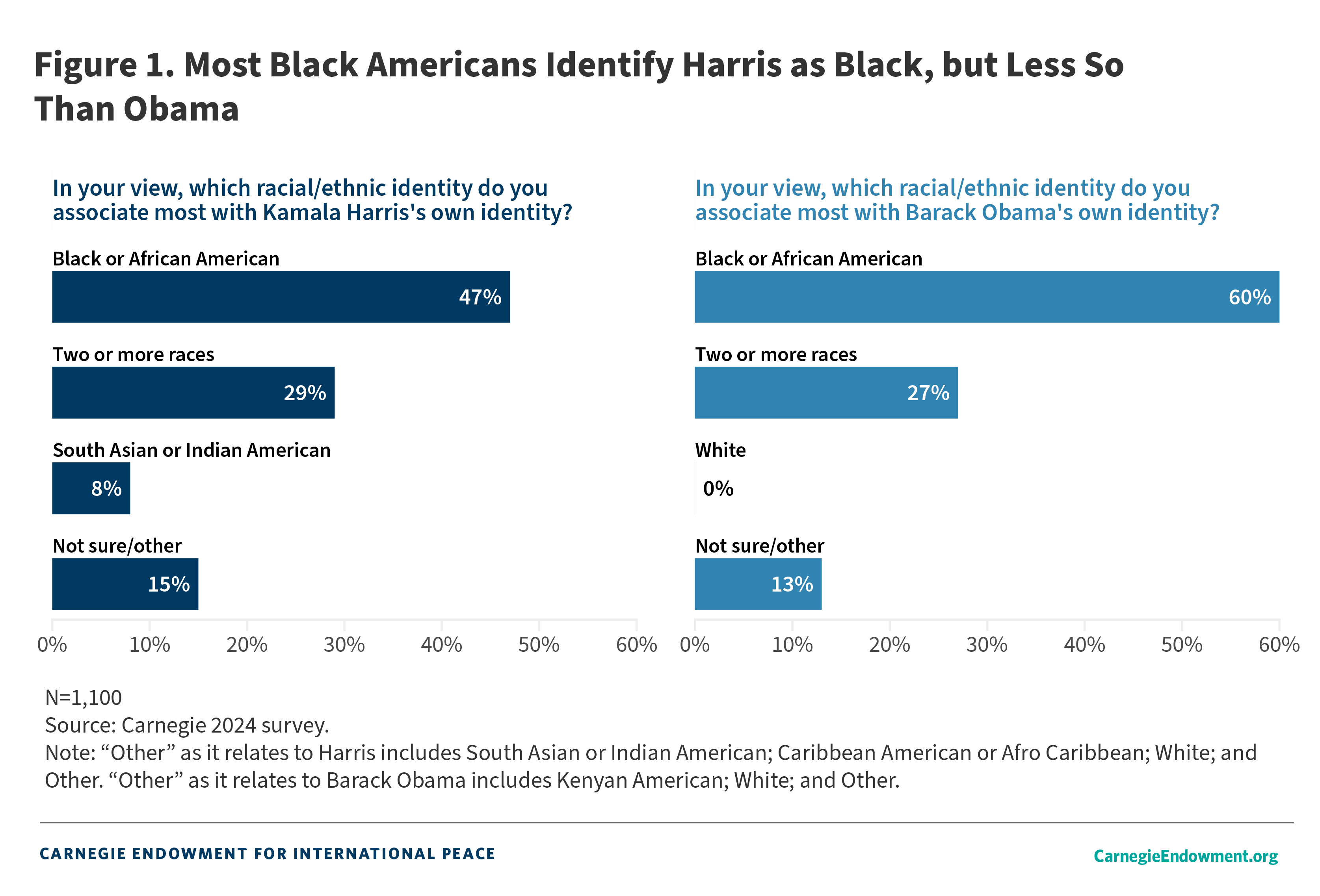

To assess whether conversations questioning Harris’s racial identity amplified doubts about her racial authenticity and lowered enthusiasm for her candidacy, we asked respondents how they identified Harris racially.

A plurality of respondents (47 percent) identified Harris as solely Black or African American, followed by 29 percent who identified her as multiracial (Black and South Asian), and 23 percent who selected “other.” The finding that nearly half of respondents considered Harris exclusively Black aligns with recent research by Good Authority showing that people’s own racial identities shape how they see her. That is to say that compared to other racial groups, Blacks are most likely to perceive Harris as being Black only, as compared to being mixed-race or South Asian only. The same holds true for South Asian people, who are more likely to view her as being South Asian only compared to Whites and Blacks.

Interestingly, Obama was perceived by 60 percent of our respondents as being exclusively Black, while 27 percent perceived him as mixed-race (Black and White) and 0 percent perceived him as being solely White—compared to the 8 percent who perceived Harris as being solely South Asian. In sum, a total of 87 percent of respondents identified Obama as being Black or half Black, compared to 76 percent of respondents identifying Harris with one of those two categories—an 11 percent difference. Complicating matters further, we found that among the 23 percent of respondents who did not identify Harris as Black or mixed-race, 75 percent identified Obama as being Black or mixed-race.

The difference in how respondents perceived Harris compared to Obama is particularly striking, as Obama—while the poll was being conducted—sounded the alarm about Black voters’ lower enthusiasm for Harris’s campaign than for his own in 2008 and 2012. The fact that fewer Black respondents viewed her as sharing their race than Obama speaks to the complex ways racial identity is understood by the American public and Black Americans and is worthy of more research.2

Although we did not test them in this survey, there are a few potential factors that may account for the Black electorate’s different perceptions of Harris compared to Obama. One possibility involves gender: it is possible that, due to gendered double standards, Harris’s racial and ethnic identity may be scrutinized more critically than that of her male counterparts, including Obama. However, it is important to note that although Black men in our sample were twice as likely to vote for Trump as Black women, there was no statistical difference between how Black men and women identified Harris racially.

Second, family networks could play a significant role in shaping public perceptions of a candidate’s racial identity. While there isn’t yet research that explicitly tests how family optics influence the electorate’s perception of a candidate’s racial identity, existing research suggests that a candidate’s family status (such as being married or having children) can shape voter evaluations. In this context, Obama’s marriage to a generationally Black American woman and his two Black children could have contributed to the image of a “Black family,” while Harris’s marriage to a White man and his two White children offered a contrasting image. This difference in family composition may help explain why members of the Black electorate were either unsure of Harris’s racial identity or did not view her as a co-ethnic.

Lastly, there is the long-standing history of Black and White racial admixture in American history, which has shaped the ethnogenesis of Black Americans. In other words, Black Americans emerged as an American ethnic group primarily out of the racial admixture of majority African, some European, and some Native American ancestries. As a result, many Black individuals are well acquainted with the fact that mixed heritage, particularly Black and White heritage, is common. For instance, prominent figures such as Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass were mixed race, but have been historically constructed as exclusively Black with little contestation. On the other hand, while Harris’s mixed-race heritage—half South Asian and half Black—is common in Caribbean countries like Trinidad and Guyana, where there is a sizable Indo-Caribbean population, it is relatively uncommon in the North American context. Some Black Americans may be less familiar with this combination, and may therefore perceive her as less distinctly Black.

The finding that respondents were less likely to view Harris as a co-ethnic compared to Obama also supports the idea that the Black electorate’s attraction to Obama based on shared racial identity, a factor political science research has identified as a key variable in Obama’s 2008 election success (particularly in terms of mobilizing Black voter turnout), was potentially not present to the same degree for Harris.

To evaluate the impact of race-based critiques on Harris’s candidacy, we asked respondents about their familiarity with such discussions. A significant majority (76 percent) reported some level of familiarity, with 39 percent being very familiar and 37 percent somewhat familiar. Cross-tabulation of these responses revealed that most Black voters who were aware of Trump’s claims (63 percent) did not find them compelling. Interestingly, 29 percent indicated they became more enthusiastic about Harris as a result of his claims. Furthermore, among respondents familiar with these discussions who identified Harris as Black or mixed-race, 34 percent reported increased enthusiasm for her candidacy. This suggests that these attacks did not discourage voter enthusiasm. On the contrary, such claims bolstered support among Harris’s base, demonstrating notable resilience among Black voters against discussions questioning Harris’s Black identity.

The notion that racial identity–based attacks may have made some Black voters more enthusiastic about Harris’s candidacy can be corroborated by pre-election voting data. For instance, YouGov polling shows that days before former president Joe Biden dropped out of the race on July 21, 2024, he was polling as low as 63.9 percent among Black voters. By August 12, after Harris became the Democratic nominee and Trump stated she “happened to turn Black” at the NABJ conference, she was polling at 79.9 percent among Black voters—outperforming Biden (for 2024) but not meeting the historic numbers of Obama’s campaigns.

However, the data also highlights a different pattern among a subgroup of the Black electorate: respondents who were unsure of her racial identity or identified Harris as non-Black. While 16 percent of these respondents reported feeling more enthusiastic about her candidacy, 18 percent reported feeling less enthusiastic as a result of discussions around Harris’s racial identity and authenticity; this suggests that although such critiques around the authenticity of her racial identity strengthened her base, they also resonated with a smaller, skeptical subgroup. This, among other variables, may help explain why Harris was unable to match Obama-era support among Black Americans.

Given the substantial body of research indicating that race functions as a heuristic in voting behavior, we were interested in exploring whether respondents’ racial identification of Harris and their knowledge of attacks against her racial identity correlated with their vote choice. Our poll revealed that, among all respondents, 78 percent intended to vote or had already voted for Harris, compared to 11 percent for Trump and 11 percent selecting other. Notably, among respondents who identify Harris as Black or mixed-race and were aware of discussions questioning her racial identity, 86 percent were inclined to vote for Harris, while only 7 percent had voted or planned to vote for Trump. In contrast, among those who identified Harris as Black or mixed-race and were not familiar with these racial critiques, 72 percent intended to vote for Harris and 12 percent for Trump. These findings suggest that awareness of attempts to question Harris’s racial identity backfired, ultimately increasing support for Harris among the Black electorate.

We did, however, find that individuals who did not view Harris as Black or mixed-race were three times more likely to report voting for Trump than for Harris (see figure 3). Interestingly, among those who did not identify Harris as Black, awareness of debates about Harris’s racial identity were correlated with increased support for Harris. Respondents in this category were slightly more likely to vote for Harris (60 percent) than those who did not view her as Black and were unaware of these racial critiques (51 percent). The number of individuals in both categories who reported voting for Trump stayed the same, implying that the attacks did not increase support for Trump.

Future Implications

In sum, it appears that the battery of attacks against Harris’s racial identity—whether from Trump, political pundits, or celebrities—galvanized Black voters in favor of her candidacy. It seems that Trump and others’ critiques of Harris’s racial identity did not sway potential Harris supporters but instead reinforced the positions of many who were both likely and unlikely to vote for her.

These findings indicate significant resilience among the Black electorate against attempts to weaken Harris’s appeal by questioning the authenticity of her Black identity. At the same time, the fact that many Black respondents viewed her differently from how she identifies herself—and that this correlates with voting behavior—highlights the complexity and variation in how Black Americans understand their racial identity and others’.

Attempts to define what it means to be authentically Black, with the goal of preventing a candidate from connecting with the Black electorate, are not new in political campaigns, as Keyes’s comments in the 2004 Illinois Senate race show. Our survey reveals that similar attempts to do the same in this election had limited impact and only resonated with a small group of respondents who did not identify Harris as sharing their race. However, the fact that more than half of these respondents still identified Obama (who is also mixed-race) as Black raises important questions about the factors that shape racial perceptions.

To this end, our research confirms that a candidate’s racial identity—or perceived identity—plays a significant role in shaping Black voting behavior. However, if the goal is to replicate Black voter support at the levels of Obama’s 2008 campaign, political parties ought to consider placing as much emphasis on policies that resonate with most Black voters. These include domestic policies like affordable housing, lower healthcare costs, workforce development, and a foreign policy that is judicious, if not restrained, when engaging in overseas military conflicts.

Additionally, if political parties wish to effectively connect with Black voters by leveraging candidates’ race, they should proactively address the evolving definition of Blackness in America. As the demographic makeup of Black America continues to diversify—encompassing individuals of mixed race or those born to immigrant parents—it is essential for political parties to acknowledge that being Black can mean different things to different voters. This could involve tailoring outreach strategies to resonate with those diverse experiences, such as highlighting candidates’ understanding of intersectional identities or focusing on policies that reflect the evolving priorities of Black communities, including those related to class, ethnicity, and national origin.

Survey Design and Methodology

The data analyzed here are drawn from a survey of 1,100 registered Black voters, designed by scholars at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and conducted by YouGov from October 8, 2024–October 15, 2024. Overall results have a margin of error of plus or minus 2.3 percent, with higher margins of error for individual demographic subcategories. In response to widespread speculation about diminishing enthusiasm among Black voters, particularly before Biden exited the race, YouGov oversampled Black Republicans to ensure the study could draw meaningful inferences about this segment of the population.

Acknowledgments

This survey was generously funded by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation.

About the Author

Fellow, American Statecraft Program

Christopher Shell is a fellow in the American Statecraft Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Haiti Is in a Crisis of State CapacityCommentary

- Lessons from Congressional Black Caucus Members’ Leadership in U.S. Foreign PolicyArticle

Christopher Shell

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

The use of technology to mobilize Russians to vote—a system tied to the relative material well-being of the electorate, its high dependence on the state, and a far-reaching system of digital control—is breaking down.

Andrey Pertsev

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Trump’s State of the Union Was as Light on Foreign Policy as He Is on StrategyCommentary

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller

- U.S. Aims in Iran Extend Beyond Nuclear IssuesCommentary

Because of this, the costs and risks of an attack merit far more public scrutiny than they are receiving.

Nicole Grajewski