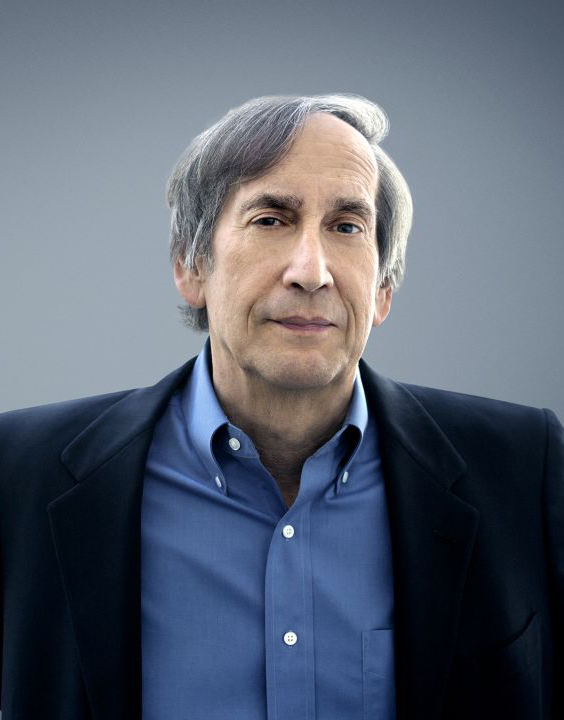

Nathan J. Brown

Source: Getty

Can Palestinian Politics Be Revived?

In order to succeed, the new proposals to transform Palestinian national institutions into viable state structures must display political realism, resonate among Palestinians, and court robust international support.

An international campaign to recognize the state of Palestine has occasioned the most intensive and detailed talk of Palestinian political reform in a decade and a half. And some of that talk is useful.

But the decay in Palestinian political institutions is so advanced, and the prospects for the Palestinian national movement so troubled, that it makes sense to shift to a different vocabulary. The term “Palestinian reform” once had a very specific meaning involving specific fiscal, procedural, legal, and constitutional changes in Palestinian governance. But it now mixes such sincere and expert meanings with others that are vacuous, disingenuous, naïve, or even hypocritical. The term no longer reflects a viable standalone project; instead it must be placed within the context of a revival of Palestinian politics in general as well as international support for Palestinian national rights.

That will be a herculean and perhaps a generational task; if it is seen as either an exclusively Palestinian or an exclusively international project, then it will fail. While there are finally signs that some Palestinian and international actors are finally grappling with what such a revival means, the task is likely be more difficult than they acknowledge.

In this article I argue first that “Palestinian reform” began as a purely Palestinian project but gained traction during a period in which it obtained international support and formed a coherent agenda. I then show how the coalition that briefly pursued the project disbanded two decades ago. While the phrase “Palestinian reform” lives on, it has tended to become purely technocratic and piously but vacuously mouthed—sincerely at first and then as an empty talisman—primarily in diplomatic circles. Finally, I demonstrate why its revival today should be treated in a respectful but measured manner according to standards that must go beyond both the technocratic and even the idea of “reform,” all the way to the revival of Palestinian politics more generally.

The Life and Death of Palestinian Authority Reform

The idea of reforming Palestinian governance—and especially the political patterns emerging with the construction of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and the Oslo process of the 1990s—was born almost as soon as the PA itself was built, beginning in 1994. And it began at the grassroots, among Palestinians frustrated at what they saw as amateurism, incompetence, corruption, authoritarianism, and unaccountability. Complaints from intellectuals and activists resonated among people who felt that their leadership had promised them a road to statehood and to self-governance but seemed powerless to attain statehood and seemed beyond the reach of those they were supposed to serve. I wrote recently,

“By the late 1990s—when the reform talk began—there was an elected president and parliament to be sure, but there seemed little prospect of a second set of elections; the parliament seemed sidelined by the executive; official positions seemed to be awarded on the basis of political connections and loyalties; and high-level officials were accorded travel privileges (and perhaps even official contracts and other favors) that allowed them to escape the effects of a deteriorating political situation.”

Internationally, the peace process stalled, and Israel and the United States stubbornly refused to recognize Palestinian statehood as a goal. But Palestinian frustration was directed not only at the “peace process” but also at the state-like structures emerging in the PA they saw as mismanaged, haphazard, and sometimes dictatorial. So projects for reform were a staple of discussions in the elected Palestinian Legislative Council (the PA’s parliamentary body), workshops held by leading Palestinian NGOs, and broader intellectual discussions. These attracted only limited international attention, but by 1999 there was a detailed set of proposals from a group of largely Palestinian public figures, supported by an international task force funded by European donors and operating under the Council of Foreign Relations in the United States.

But despite such episodic attention (and sometimes careful documentation and proposals), the project gained little traction. For the senior Palestinian leadership, and particularly the PA’s elected president, Yasser Arafat, the focus remained very much on obtaining the goal of the Palestinian national movement—a Palestinian state. National leaders did not wish to be tied down to domestic rules and procedures. Elected Palestinian parliamentarians thus drew up whatever laws and plans they liked, but the most critical ones simply sat in the president’s inbox.

For the senior Palestinian leadership, the focus remained very much on obtaining a Palestinian state.

And the reports, draft laws, and proposals sparked little interest outside. To Israel’s leaders, the attraction of the “peace process” (as it was then called) was their own state’s security—which meant a Palestinian leadership willing to accept limitations on sovereignty and willing to cooperate in guaranteeing the security of Israel and Israelis. Such leaders were left uninterested in reform: Critics increasingly decried the PA as simply a subcontractor for the occupation. And while international donors helped with specific projects—and documented areas where reform might be seen as needed—the international sponsors of the peace process (chiefly the United States, but also Europe) focused their attention on Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy. Internal Palestinian governance issues were an annoyance, not a priority.

But in the early 2000s, that dynamic suddenly shifted. And oddly it was the outbreak of the intifada that provided the impetus for the sudden formation of a reform coalition. Domestically, the weakness of Palestinian institutions became painfully clear to residents of the West Bank and Gaza. But only after 2000 was the former taboo on talk of the two-state solution broken in the United States and, to a lesser extent, Israel. The phrase implied acceptance of the principle of a Palestinian state (though one exercising something far short of sovereignty) in the West Bank and Gaza. But Israeli and U.S. leaders began to see Arafat as an obstacle, unwilling to rein in (and perhaps even egging on) the violence. So the idea of reform gained new salience as a tool against Arafat: If reform limited his authority, then it could contribute to a diplomatic solution. The idea that reforming the PA was part of a path to statehood became axiomatic—for a brief period.

So between 2001 and 2006, a powerful coalition of Palestinian figures and international donors pushed through parts of that program. The European Union conditioned assistance on some elements; the United Nations Security Council included other elements in its 2003 road map; the Palestinian Legislative Council adopted relevant legislation; and the coalition imposed many changes on a reluctant Arafat, who had been more comfortable operating in an ad hoc, personal, and often opaque manner. Partly because the effort was public and often publicly funded, the reform wave was easy to follow and document, as were its accomplishments: the adoption of a constitutional framework, other foundational laws covering everything from the civil service to the judiciary, more regularized fiscal practices, and parliamentary oversight of the executive.

But the coalition proved to be self-limiting in an unanticipated way. Because constitutional reforms and elections were central to the reform program, the wave included elements such as an empowered parliament, clear political responsibility for a prime minister and cabinet (including the minister of interior and thus security forces), and presidential, local, and parliamentary elections. Arafat’s death brought the election of Mahmoud Abbas, who was seen as supportive of reform. (He had been the first to occupy the prime minister’s post and resigned complaining that he was not able to use the tools afforded to him.) Local elections came with a strong showing by Hamas, but the top issues for voters were primarily good governance and local concerns. In a sense, the reform movement was proving itself not simply a cause for intellectuals and international bureaucrats but also a very popular idea domestically—so much so that the 2006 parliamentary elections were run partly on the promises of various actors to deliver reformed governance. Hamas ran under the banner of “Change and Reform,” and Fatah activists strove to distance themselves from the movement’s reputation for converting the PA into a patronage machine (or a set of machines that allowed various leaders to build up local or institutional fiefdoms within PA structures).

The reform movement was proving itself not simply a cause for intellectuals and international bureaucrats but also a very popular idea domestically.

Hamas’s ability to translate its electoral plurality into a parliamentary majority—due in large part to an electoral system that had been produced as a way of managing Fatah infighting—burst the reform coalition asunder. International actors quickly abandoned the cause, horrified at what their embrace of elections had wrought; Fatah leaders held on to the positions they retained regardless of the new laws and procedures; and Hamas was saddled with the impossible task of turning a reform-oriented platform into a governing program in the face of international boycotts and internal opposition (from the president, the bureaucracy, and the security services).

After one year, the fragile Palestinian political system simply broke in two, with the West Bank under the president and Fatah and Gaza under Hamas and the local parts of the PA it still controlled. By 2007, I felt able to write a requiem for Palestinian reform. The project was dead. But the phrase has lived on.

Posthumous Attempts at Reform

In the years after 2007, Palestinians saw division, suspension of the Parliament and parts of the Basic Law, rule by decree, and the decay of the statehood project: precisely those outcomes the reform movement was designed to counteract. But international actors who had briefly backed Palestinian reform saw such authoritarian moves as necessary to remove Hamas from governance. By turning against the democratic or legal aspects of reform, and by abandoning key parts of the Oslo Accords (such as those governing security arrangements, interim Israeli withdrawals from West Bank territory it still occupied, freedom of movement, and even bilateral mechanisms to deal with “incitement”), international members of the reform coalition (most European actors and especially the United States) abandoned the content of Palestinian reform.

This abandonment often took disingenuous forms. In the past few years, for instance, the failure of Palestinian officials to hold elections is often cited by those same forces that actively supported the overturning of the last ones and who failed to support Palestinian efforts to hold new ones. Security sector reform supported more professionalized and effective security coordination with Israel but abandoned any efforts at effective civilian oversight, ending Israeli incursions in PA-controlled Area A, allowing PA civil institutions to operate as agreed even in Israeli-controlled Area C, or restoring Palestinian institutions in Jerusalem allowed under Oslo side agreements.

Strangely, it was during this period that the phrase “two-state solution” became ubiquitous in international circles. It was proclaimed as the only possible outcome by those who did not have a clue how to bring it about. By mid-2007, I was able to write:

“Those who pretend that history is moving toward a two-state solution have actually hastened its demise. The most convincing argument for continuing efforts on the two-state path is the unattractive or unviable nature of the alternatives. That may make the mission more important, but it makes it no more likely.”

To be fair, not all the international reform talk was hypocritical or insincere. Much was merely naïve. This was most obviously the case during the period after 2007, when there was an attempt to build up the Ramallah-based PA with an ambitious array of technocratic reforms. Under the premiership of Salam Fayyad between 2007 and 2013, Palestinian leadership (with robust international support) pursued important but isolated parts of the former reform agenda—those that were not about accountability, democracy, or freedom but about technocracy, sound fiscal practices, civil service reform, and clear procedures. While lauded by then Israeli president Shimon Peres as Palestine’s version of Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion for his pragmatic policy, Fayyad might be better seen as its Felix Rohatyn (the Wall Street financier brought in to oversee New York City’s emergence from acute fiscal crisis in 1975). But unlike even Rohatyn, Fayyad was operating in the context of intensive settlement activity and continued suspension of critical elements of the Oslo Accords—and other elements were only in force in the West Bank. Any efforts to reunite the West Bank with Gaza were unacceptable to Israel and the United States.

The reform steps of this period were salutary in many ways, but they were not a road to statehood, as should have been clear at the time. Nor did they have any tenable political foundation. The project was inherently limited by a number of factors, among them: the technocratic nature of the program, the powerlessness of Palestinians to shift Israeli policy, and the ineffectual international efforts to go beyond mouthing support for a long-moribund peace process. Without any popular base but with strong international support for him (and him alone) as a person, Fayyad’s leadership was experienced by those on the West Bank as something of a highly personalized international protectorate—and one that ultimately provided little protection. Fayyad himself is retrospectively very thoughtful about the limitations of the attempt.

The reform steps of this period were salutary in many ways, but they were not a road to statehood, nor did they have any tenable political foundation.

With the end of Fayyadism in 2013, there was little left even of the technocratic version of Palestinian reform. Yet the slogan of “reform” lived on, often simply as a way of denouncing, dismissing, or sidelining the existing Palestinian leadership as corrupt, ineffectual, and unpopular.

So what meaning did “Palestinian reform” take in such a context? When Israeli leaders talked about specific measures, they chose the measures that served their own interests (security coordination) or that advanced specious demands to impose changes on the PA education curriculum or its support for prisoners, employing ill-informed and baseless claims about both. The endless repetition of the supposed problems that needed reform made them axiomatically true in prevailing Israeli discussions. (One senior Israeli diplomat once asked me after I presented research on the subject, “Do you mean to tell me I have been lying?”) These same charges were accepted unquestioningly by parliamentarians in Europe and members of the U.S. Congress and have even been mouthed mindlessly by former senior officials and written into policy and law. The evident motive behind the charges was not so much to secure changes as to place unattainable demands in front of a Palestinian leadership, effectively making viable two-state diplomacy not simply improbable but illegal.

And the effect on any genuine reform among Palestinians was sharply negative: It communicated to Palestinian officials and to the broader public that the PA structures would only be supported internationally if they could satisfy an Israeli leadership that sought to reverse the entire Oslo process—a standard that was, by definition and design, impossible to meet and that deeply discredited PA leaders who made feeble efforts to satisfy insatiable demands.

It communicated to Palestinian officials and to the broader public that the PA structures would only be supported internationally if they could satisfy Israeli leadership.

Indeed, Palestinian leaders have been willing to patiently listen to mid-level officials talk about reviving some of the reform program (for instance, reversing executive attempts to subordinate the judiciary). They have apparently been confident that they can parry demands about governance since most are unlikely to be pursued seriously—and, if they are on rare occasion, they can be met with technical palliatives. To be fair, it is not merely self-interest that motivates PA leaders. There is plenty of jockeying for position and ambitious maneuvering over the increasingly hollow central positions of Palestinian politics.

But there is also a historical sense that motivates aging PA leaders: They present themselves as heirs and caretakers of a national movement that has established itself after great efforts both domestically and internationally. That movement will only resume its march toward its goal of Palestinian national self-determination if its leadership is unified. And, they say, that will not happen by incorporating challengers like Hamas, holding divisive elections, tying down leaders with rules and procedures, denying them the flexibility to respond as needed in a perilous environment, or allowing excessive backbiting and criticism of leaders who have proved their revolutionary mettle.

But if that is how members of the leadership see themselves, it is striking how little such images are attractive to Palestinians. Indeed, in private conversations, even senior leaders can come close to acknowledging that they are a spent force devoid of strategy. Even their dwindling numbers of supporters decry their passivity in the face of the most challenging circumstances Palestinians have faced as a national community. To be fair, the current leadership has few cards to play. But over the past two years, their passivity has been punctuated only by brief bouts of reactivity whenever an international opening appears; when that fades, they simply pray for rescue.

And most Palestinians are not very charitable in their evaluations. By 2023, almost any discussion with Palestinians in the West Bank ranged among cynicism, alienation, and despair. And those elements became more pronounced the younger the interlocutors. With no positive memories of the triumphs of the national movement but only of steady deterioration on almost every political, social, and economic level, most I spoke with two years ago felt betrayed, leaderless, and abandoned. And it was hard to disagree. With the Gaza war, matters have decayed so far that I was able to speak a year ago of “Palestinians without Palestine,” meaning, “Palestine seems to have come to a full stop. Its institutions have withered rather than evolving into a state. But Palestinians are still very much present—not merely as individuals but as a national community.”

Reviving, Not Reforming Politics

In recent months, there have been a series of official and unofficial efforts to sketch out practical steps that can be taken to empower the PA and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), reform them, and transform them into a viable, accountable, and peaceful Palestinian state. And they move beyond merely invoking discredited phrases like “peace process,” “reform,” and “two-state solution.” While they sometimes mention the latter two, they accompany them not with hortatory but with long lists and bullet points that contain practical details. They display some political realism, acknowledging at times how dire the situation is for individual Palestinians and the Palestinian national movement, and they are anchored far more deeply in Palestinian political realities than in attempts to placate international audiences.

Each one has its blind spots, to be sure. The July 2025 New York Declaration may be the most detailed. It is the thirty-page outcome of a joint Saudi-French-led and United Nations–sponsored High-Level International Conference for the Peaceful Settlement of the Question of Palestine and the Implementation of the Two-State Solution. It consists of not only a lengthy and detailed set of diplomatic measures and provisions but also an annex with details on everything from banking to internet access. And rather than sidestep difficulties, the drafters appeared very well informed of the developments of the past twenty-five years. The effort is serious and sustained. And it focuses on revival of muscular diplomatic efforts. But it becomes a bit reticent or retreats to generalities on anything that might require what was considered reform a generation ago (such as practical steps to guarantee judicial independence or parliamentary oversight of the executive).

Over the past year, a new unofficial body, the National Conference for Palestine, has emerged. This body is far more insistent on criticizing the governance practices of the existing Palestinian leadership; its statement reflects a desire to rebuild a national movement, connect leaders to their constituents, manage deep divisions among Palestinians, and develop structures for national strategy and decisionmaking. But it is rooted primarily in intellectual and opposition circles, and therefore the leadership regards it as hostile and lacking broad-based support both among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza and from potential international supporters (other than Qatar, where the group has met).

A very extensive March 2025 report by the Israel Policy Forum, “No Time to Lose,” presents an expert set of proposals drawing primarily on English-language sources, but ones that seem informed by ideas discussed over a long period by Palestinians and diplomats on the scene. While many of its detailed proposals thus draw from earlier versions of Palestinian reform proposals, the document’s provenance (in terms both of its authorship and sponsorship) leave it likely to be ignored both in Palestinian and Israeli societies. It is based on the idea that a strong PA leadership bolstered by reform efforts will be a viable partner for Israel—a viable intellectual position, perhaps, but one deeply out of tune with Israeli political discourse and likely to render it very suspicious in many Palestinian eyes.

The gaps and blind spots of these and other recent efforts are not easy to fill. There is a clear set of lessons from the quarter-century in which an intensive (though brief and troubled) period of Palestinian institution building was followed by decades of decay. But the lessons are not always palatable ones. They suggest that real change will only occur when what is seen as reform has domestic resonance, muscular international support, a viable diplomatic process, and at least acquiescence from the Palestinian and Israeli leaderships. In the absence of such elements, “reform” will become merely a slogan or a shopping list of suggestions that changes from one user to the next. Any real change will quickly run afoul of deep divisions. Merely technocratic reform will be seen (generally accurately) as attempts to serve some purposes but not others; core elements of what constitute reform for some quarters (Palestinian reconciliation most notably) is an anathema in others.

Real change will only occur when what is seen as reform has domestic resonance, muscular international support, a viable diplomatic process, and at least acquiescence from the Palestinian and Israeli leaderships.

And most significantly, close to two decades of turning reform into a bromide has bred cynicism and despair among its potential champions and beneficiaries. The context of the efforts a quarter-century ago is a distant historical memory for most; any effort to reform institutions must confront the deep record of the intervening years.

The Real Revival Agenda

Any successful effort to revive Palestinian politics will have to grapple with a series of difficult realities. While none of these can be easily addressed, the seriousness of an attempt can be measured by its designers’ willingness to face up to some core issue. In other words, the various visions listed above (or the new ones to come) can be evaluated by whether they pretend the context of the 1990s still exists or whether they acknowledge and even make forays at dealing with the following tasks.

- Grappling with Gaza: Of course there are likely to be tremendous humanitarian, security, and governance issues if the assault on Gaza ever ends. But much more will be necessary. Discussions of “the day after” often focused on the logistical, administrative, and security framework, for good reason—they will be difficult to devise in a way that can operate. An international framework for providing education, healthcare, and food has been partially dismantled; the most experienced and credible actors sidelined; and key personnel subject to expulsion, abuse, and sometimes death. But that is just the tip of the problem. The extent of destruction and trauma is simply so profound as to be almost inexpressible—with the majority of the population relocating more than once; no homes to go back to; schools, universities, and many public buildings destroyed; economic infrastructure targeted; and a population that has spent two years devising ways to find shelter, food, water, electricity, and medical care.

- Restoring a sense of normality in the West Bank: With entire neighborhoods destroyed, Israeli reoccupation of some cities, universities sometimes resorting to remote instruction, salaries of public servants slashed, the banking system on the verge of isolation, some villages depopulated and others targeted by Israel settlers, and movement among the towns and villages uncertain, the level of trauma will seem tame only by comparison to Gaza.

- Coaxing the Palestinian leadership: The PA and the PLO are controlled by a small number of figures who are not merely aged but also lack strategy or direction, sometimes devoting their remaining energies to jockeying against each other. And yet most leaders remain deeply suspicious of any attempts to hold them politically accountable to anything other than their own sense of mission. Almost all efforts at revival depend at some point on elections, and it is difficult to envision any revival of Palestinian politics that does not allow for balloting on the local and national level. But given current conditions in Gaza, the fears of the leadership of the divisive effects of truly competitive elections, and the international aversion to elections that allow Hamas to run, elections will be difficult indeed. The current effort to hold some crude sort of elections for the Palestinian National Council will be a test of whether they can be held in a credible manner. And that seems a test that the leaders are likely to fail.

- Fixing the limits of consensus and debate: Even if successful elections are held or some truly pluralist political bodies emerge, Palestinian politics has always been bedeviled by a failure to strike a balance between national unity and competitive politics. Calls for unity are legion, but they seem to be either insincere slogans or exercises in papering over differences with vague formulas. There are structures—such as the Palestinian National Council for the PLO and the Palestinian Legislative Council for the PA—where vigorous debates have taken place, and there have been many informal sessions, sometimes out of public view, where various points of view have been debated. But what Palestinians have lacked is a process in which all voices are heard and decisions are taken.

- A civil society that involves society: Any revival of Palestinian politics will have to involve not simply a renewed political leadership at the top but also a revival of civil society—with that term understood not as simply a small number of highly professionalized nongovernmental organizations but a broad set of unions, youth clubs, local voluntary organizations, and neighborhood associations.

- Engaging the diaspora: One often-underappreciated aspect of Palestinian politics over the past few decades has been the attenuation of ties with the diaspora. From the 1960s until the signing of the Oslo Accords, the PLO provided an umbrella—albeit one of uneven effectiveness—for much Palestinian political, social, and even economic activity. As a structure and symbol, it was a common point of reference for Palestinians throughout the world. It has atrophied. In recent years, diaspora voices have tended to be either deeply critical or completely disengaged. Drawing on the talents and support of the diaspora will not be possible until there is a national leadership that can claim support at least from the population of the West Bank and Gaza.

- Engaging youth: The alienation of Palestinian youth is not a mere matter of dress or morals (though the generation gap exists on such levels as on every other) but is based on a profound sense among younger Palestinians that their leaders, their national movement, and most global structures have utterly failed them. It is difficult to overstate how profoundly the politics of the past—not just Oslo but also the PLO, the PA, and even intifadas and Arafat—are recalled, if at all, with little content.

Roadblocks, Not Road Maps

Palestinians express a clear desire to live in a political system that is accountable to them and that governs in a transparent manner, respecting their individual and national rights. And on a formal level, they have the support of most international actors for that goal (including the vast majority of members of the United Nations and now some key European actors) within the context of a state of Palestine. The territory of this state is clear in the minds of the leaders at least: While it attracted no attention, the recent electoral decree for the PLO’s Palestinian National Council explicitly defined Palestinian territories as those occupied by Israel in 1967 (this phrasing has been in effect since at least 2009). While few Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza regard talk of the two-state solution as credible, their attitudes are based on a sound understanding of the realities of the past decades, not on an unwillingness to come to terms with the reality of Zionism. Yet the path to an accommodation of the national and individual rights of all inhabitants of Israel/Palestine will be long, and its outcome is uncertain. Reviving Palestinian politics will be a critical part of any such accommodation. But that necessary condition is one that faces intense resistance.

Reviving Palestinian politics will be a critical part of any such accommodation. But that necessary condition faces intense resistance.

Both popular and governing Israeli attitudes have changed so radically over the past quarter-century—and become so extreme in the past two years—that any successful efforts to revive Palestinian politics will have to overcome not simply profound Israeli skepticism but deep and expert Israeli attempts to undermine them.

For a decade after the initial signing of the Oslo Accords, Israel was led by figures who agreed to treat Palestinians as a national community and to do so through their acknowledged leadership. But their willingness to entertain the construction of a Palestinian state was never as unequivocal as is remembered. (Prime minister Yitzhak Rabin publicly opposed Palestinian statehood; the idea was endorsed by some of his successors only with limitations sufficiently stringent that it is not clear if they meant anything other than a protectorate.) But despite their reticence, those in the highest positions understood Israeli security as being enhanced by some accommodation with those who could speak for Palestine. It is not just that that position is rejected by the current leaders; it is that they are joined by most of the opposition and that their enmity to the idea is profound and with deep rhetorical and practical effects. Equating the PA with Hamas; describing a Palestinian state as an existential threat; blood-curdling rhetoric about Gaza; descriptions of Palestinians as “Amalek”; observations (from the highest levels of the state) that Palestinian civilians are not innocent; and clear moves in the direction of ethnic cleansing are the verbal face of this—and the fact that political leaders speak this way to their domestic audiences suggests they feel their positions are popular. But the position goes far beyond words: There is a clear effort to atomize the Palestinian population, rearrange them demographically, undermine their institutions, and restrict their movements and activities in a manner that goes beyond ignoring Palestinian leaders to deeply undermining them.

The war in Gaza seems to have brought home this point to many who had resisted the realization of the shift within Israel. There is no other way to understand swings in the positions of some European states who are now recognizing Palestinian statehood, the marked change in much European discussion of Israel and Palestine, and even the upsurge of efforts among Arab leaders to forge some common initiatives. So the task is now clear to many in the international community, but what is less clear is whether they have the wherewithal and tools to induce a change in Israeli calculations.

And here the United States is a major obstacle, not the boundaries of debate that have expanded beyond all recognition. Trends similar to those in Europe are very audible on the American left, even (or especially) among American Jews. They are sometimes heard on the right as well—but in other circles, there is growing friendliness to the most extreme Israeli positions, including calls for Jewish sovereignty for all territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea (with no citizenship for Palestinians in the territories to be annexed).

Conclusion

Such voices are heard at the official level, but there is still a somewhat narrower spectrum. Much of the effort to undermine Palestinian politics is written into American law. At their most friendly, executive branch officials sometimes soften the edges of policies that effectively undermine the feeble, surviving institutions. In many policy discussions in Washington, some of the older, problematic talk of idiosyncratic reform lives on, but it is easily discernable: decrying the failure to hold elections without consideration of what serious elections would require, talking about the need to change textbooks or replace them with ones from the United Arab Emirates, demanding unilateral changes by Palestinians to support a peace process that died long ago, or denouncing PA corruption without understanding its meaning in a Palestinian context (the inability of those who enjoy the perquisites of senior positions to produce any clear strategy or even tactics).

There may be a path out of Palestine’s predicament that can accommodate both Palestinian and Jewish nationalism, but if there is, it is a difficult one. The most positive shift in recent months is that some of the talk of Palestinian reform is coming to grips with what really needs to be done. There is nothing like the international and domestic consensus of a quarter-century ago, but the proposals that are floated increasingly show attention to detail, engage seriously with politics, and predicate themselves on Palestinian political realities rather than the Israeli or international demand du jour. And some have begun to bridge the gaps in Palestinian society, such as between official and unofficial circles and between Palestinians and international supporters.

That energy is a positive sign, but it will be wasted without a serious effort to overcome the internal and external obstacles it faces.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Nathan J. Brown, a professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University, is a distinguished scholar and author of nine books on Arab politics and governance, as well as editor of five books.

- For Younger Palestinians, Crisis Has Become a Way of LifeArticle

- The Perils of the Palestinian Authority’s New Party LawCommentary

Nathan J. Brown

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

The use of technology to mobilize Russians to vote—a system tied to the relative material well-being of the electorate, its high dependence on the state, and a far-reaching system of digital control—is breaking down.

Andrey Pertsev

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Trump’s State of the Union Was as Light on Foreign Policy as He Is on StrategyCommentary

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller

- Can the Gulf Cooperation Council Transcend Its Divisions?Article

Without structural reform, the organization, which is racked by internal rivalries, risks sliding into irrelevance.

Hesham Alghannam

- Notes From Kyiv: Is Ukraine Preparing for Elections?Commentary

As discussions about settlement and elections move from speculation to preparation, Kyiv will have to manage not only the battlefield, but also the terms of political transition. The thaw will not resolve underlying tensions; it will only expose them more clearly.

Balázs Jarábik