Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

By Armenak Tokmajyan

For settled descendants of nomadic or seminomadic communities on Jordan’s periphery, the future looks uncertain as government employment is declining, natural resources are dwindling, temperatures are rising, and traditional cross-border ties are restricted.

East of Irbid, northern Jordan’s largest city, begins the arid and semi-arid Northern Badia district. Along the road to Baghdad, before reaching the city of Mafraq, a late spring breeze gives way to scorched wheat fields that have withered before ripening, with small wild shrubs clinging to life. As one plunges deeper into the desert, the terrain changes. Brown earth becomes flecked with small black basalt rocks, as if the sky had rained stone. However, it isn’t the rocks that seem out of place, but the bursts of green: grapevines and peach orchards, cultivated patches of land defying the aridity, irrigated by underground water. Nearly two-hours out of Irbid, one reaches scattered villages making up the Deir al-Kahf subdistrict of Mafraq Governorate, home to some 15,000 people, settled descendants of nomadic or seminomadic Bedouins living on Jordan’s periphery near the border with Syria.

The remote desert region offers an instructive illustration of how overlapping economic, environmental, and climate-related factors are reshaping Northern Badia’s socioeconomic landscape. The settlement of Bedouins, those of Deir al-Kahf included, was central to the formation of the Jordanian state and its northern and eastern borders. From the Mandate period (1921–1946) until Jordan’s independence, and especially after 1970, this process reshaped local economies when the state greatly expanded its hiring among the population and encouraged agricultural development projects that encompassed the semi-arid steppes east of the Hijaz railway.

However, in the past decade the impact of climate change, particularly rising temperatures, has become clearly perceptible. Even the more optimistic projections are deeply troubling, threatening to render an already neglected land increasingly inhospitable. Climate has long influenced the region, transforming a dominant nomadic lifestyle from as early as the 1920s. The decline in state employment opportunities and the fact that capital-intensive, export-oriented development projects largely favored external investors, with little concern for creating local jobs or protecting natural resources, have left residents facing increasingly difficult choices, which will only intensify migration to Jordan’s cities.

Displacement is usually cast as a grim coping strategy for settled communities, uprooting them from their livelihoods and landscapes. For seminomadic groups, however, the inverse can be true: settlement can be a form of adaptation. Beginning in the 1920s and after decades of resisting settlement under Ottoman rule, most Bedouin communities in Jordan’s steppes gradually exchanged their tents for stone houses in response to opportunities provided by the state, harsh climatic episodes, and the state’s steady advance into desert life. This led the communities to replace pastoral and agropastoral pursuits with state employment and subsidies, as well as integration into state-backed development schemes.

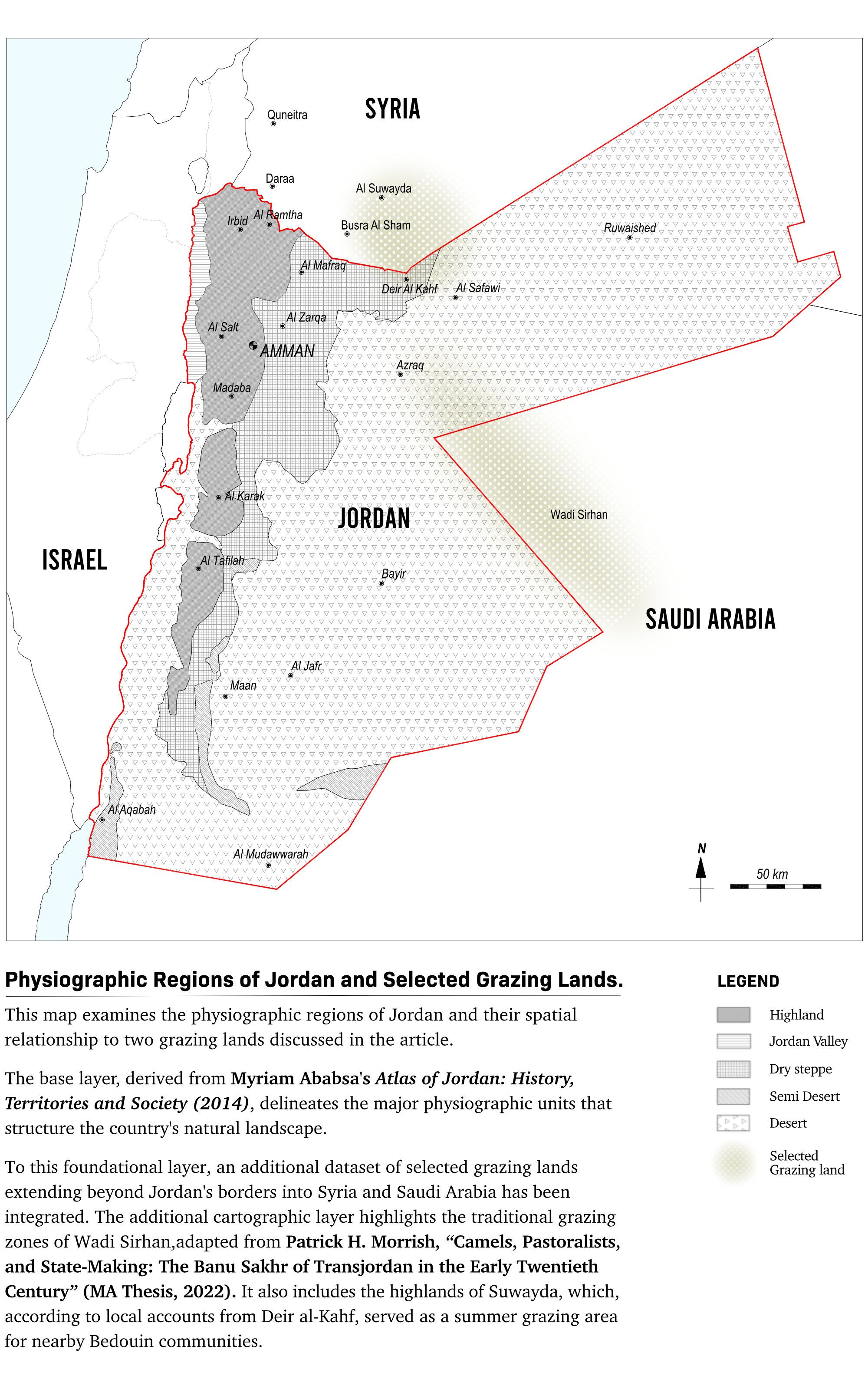

That transformation was well-captured by the formation of the Jordan-Saudi border in the 1920s, which coincided with a near-decade-long drought beginning in the middle of the decade.1 The drought eroded the Bedouin communities’ resilience, while the forces of Abdel-Aziz Al Saud, who became king of Saudi Arabia in 1932, carried out repeated raids and eventually imposed a border accepted by the British Mandatory power in 1925. These two factors depleted the Bedouins’ livestock and placed the region’s most important grazing land, the Sirhan Valley with most of its permanent wells, inside Abdel-Aziz’s territory, making it off limits to Bedouin tribes on the Jordanian side (see Map 1). This pushed many tribes, even those that were well-off, to the brink of starvation.2

The damage done to the Bedouin communities was the Jordanian state’s gain.3 In 1930, John Bagot Glubb, then the commander of the Desert Patrol, a force made up primarily of Bedouin, was tasked with stabilizing the frontier with the emerging Saudi kingdom and securing a vital link between Palestine and Iraq, both under British Mandate. Glubb’s “militarized welfare” combined recruitment into his new force with handouts, seed loans, sheep, and occasional paid work. This rescued Bedouin communities from economic collapse, prevented defections to Abdel-Aziz’s forces, and curbed cross-border raids. Over time, Glubb integrated seminomadic tribes into the Mandatory state, now centered on Amman. In doing so, he laid the foundations of a social contract between the center and tribal peripheries—an enduring pact that saved the Hashemite monarchy in many crises.4

The Syrian-Jordanian border’s formation had a similar impact in confining Bedouin communities within a national framework and disrupting their grazing areas. When Britain and France drew the border between their Mandates in 1932, Northern Badia was cut off from Suwayda, where Deir al-Kahf’s Bedouins, among other Bedouin communities, grazed their herds before returning to Jordan in winter. However, there was weak enforcement of cross-border grazing, which continued until 1970, when controls were tightened after Syrian-Jordanian hostilities following the Jordanian army’s clashes with Palestinian groups.5

If borders confined the Bedouins within national boundaries, the growing efficiency of the state, both the Mandatory and independent state, further altered the Bedouin reality. The state expanded its bureaucracy, especially the army and security forces, which attracted Bedouin communities in particular. By the early 1990s, two-thirds of all jobs in Jordan were in the public sector, which absorbed 60 percent of educated labor market entrants. By then, sedentarization was nearly complete. In the 1920s, 50,000 people were estimated to be nomadic and 120,000 seminomadic, while during the 1990s most had been sedentarized. The army also expanded—from 8,000 soldiers after World War II, to 17,000 in 1953, 55,000 in 1967,6 and over 100,000 by 1999—sustained first by British, and then by U.S. and Arab subsidies. This reshaped rural society. By 1970, as many as 70 percent of rural Jordanians benefited from the army, whose ranks increasingly included newly-settled Bedouins.7

These shifts profoundly altered Bedouin livelihoods. In the late 1990s, it was rare to find Bedouin families fully reliant on farming or herding. While many still kept sheep, acquired land, or practiced limited cultivation, state employment had become the main source of sustenance. With the modern state’s expansion into the hinterland came planning and growth, as well as new market forces and external capital. These shifts created opportunities, such as access to groundwater and land ownership, as well as rural development projects. However, in Deir al-Kahf or other places, such as Azraq and the Northwestern Badia, the benefits were largely captured by outside investors, whose capital-intensive, unsustainable farming methods disregarded the environment or local communities.

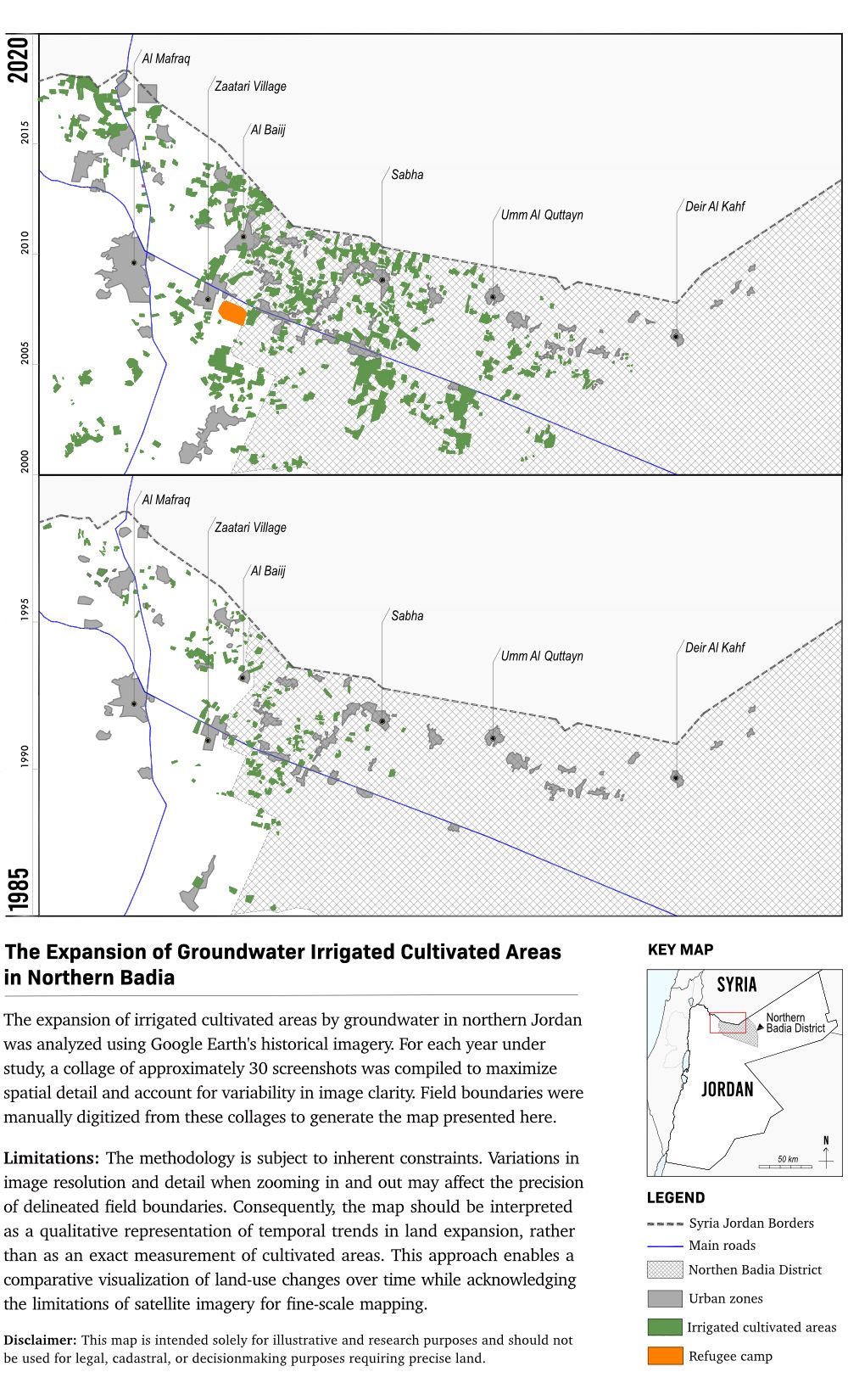

The state’s penetration of the steppe transformed land ownership and access to water. Beginning in the 1960s, the state granted licenses to access ground water, with little oversight. Demand for agricultural land in semi-arid regions (previously almost nonexistent) began to rise in the 1970s. Cheap water and land invited investment and the result was a mixed form of agriculture. On one end was “traditional” cultivation—low-intensity, modestly profitable, using rudimentary techniques, and often paired with livestock or local wage labor. On the other were modern, capital-intensive, groundwater irrigated orchard and vegetable farms, dominated by absentee landowners—emigrants or urban elites—who relied on foreign labor and targeted lucrative export markets. It was the latter model that prevailed, embodied by the East Ghor project of the 1980s and visible in the Azraq Basin, where some 90 percent of landowners reportedly lived in cities.8

In Deir al-Kahf, a similar pattern was evident. Locals gained access to land and water in the 1970s, yet most were unable to exploit this and sold their land for profit. Precise figures are lacking, but anecdotal evidence suggests that most investors came from outside the area, attracted by cheap land, water, and local labor.9 Among the most prominent were Palestinians expelled from the Gulf in 1990–1991, who invested in agriculture.10 Satellite imagery supports local accounts showing cultivated land spreading in Deir al-Kahf in the early 1990s.

The main role of youths in this agrarian economy was to be day workers in the fields. But they were increasingly replaced by cheaper Syrian labor after the Syrian refugee crisis in 2012. For instance, many women from Deir al-Kahf who used to work in agriculture lost their jobs to Syrians. To compensate, every day around thirty vans, each carrying fifteen to twenty women, travel to Azraq, where the women work in textile workshops for barely 230 Jordanian dinars ($325) monthly.11 The influx of Syrians was a golden opportunity for investors given that labor costs were reportedly very high in their overall business expenses, sometimes reaching 55 percent.

In terms of sustainability, there is good evidence suggesting that agrobusinesses contributed to environmental degradation, of which water is the best evidence. Nationally, groundwater use in 2019, or the abstraction level, was 618 million cubic meters (mcm), some 200 mcm above safe yield levels, with 59 percent going to domestic use and 36 percent to irrigation. In the Deir al-Kahf area, which is split between the Zarqa and Azraq groundwater basins, safe yields are 87.5 mcm for the Zarqa Basin and 24 mcm for the Azraq Basin, while the abstraction level in each is 165 mcm and 69.7 mcm, respectively. Accessing water is becoming more difficult by the year, while cultivated land has dried up due to the inaccessibility of ground water.12

With regard to livestock, there are some 28,000 sheep in the Deir al-Kahf subdistrict.13 Most owners are from the Badia, but as one community leader explained, over the years ownership has been concentrated in the hands of some fifty individuals, marking a sharp departure from the past when ownership was more equally distributed.14 The high costs of sheep maintenance have left small farmers at a disadvantage. Owning even a minor herd of a few dozen sheep is expensive and risky, with the costs tied to volatile markets.15 A comparative study of sheep production systems from 2012 estimated that under the common transhumant system—where herds graze around a permanent base but migrate seasonally—maintaining fifty sheep costs about 26,000 Jordanian dinars ($36,000). Profitability requires capital, access to higher-paying markets such as Saudi Arabia, and resilience to disease and fodder price shocks. For most people in Deir al-Kahf such barriers are prohibitive, so many keep only a few sheep for household use.

All interlocutors from Deir al-Kahf voiced frustration with being unable to take advantage of available opportunities as their traditional economy eroded. Most troubling, however, was the decline in state employment and growing competition for jobs. Data support this trend. Public employment in Jordan dropped from 63 percent in 1992 to 32 percent in 2019 and rose slightly to 37.3 in 2024. The share of educated new entrants absorbed by the state fell from 60 percent in the 1980s to just 30 percent by the beginning of this century. Among young men (fifteen to twenty-four), unemployment rose from 25.4 percent in 2010 to 44.8 percent in 2024, peaking at 51 percent in 2022. For young women, it climbed from 54.8 percent to 60 percent during the same period, with a peak of 81.1 percent in 2022.

Public-sector hiring once prioritized geography through the Civil Service Bureau (CSB), giving residents of places such as Mafraq better opportunities due to the relatively limited competition for jobs. For lower-level public jobs that were once filled locally, authority was gradually centralized under the CSB and ministries, restricting local hiring autonomy. In 2022, the CSB was replaced by the Public Service and Administration Commission as part of public-sector reforms, shifting from geography-based recruitment to direct competition within ministries. This reduced opportunities for peripheral areas such as Deir al-Kahf and made applicants’ skills and experience decisive.

Cheap land, access to water, and rising global demand for meat created an incentive for investors to pursue capital-intensive, high-profit agriculture. If early in the twentieth century Bedouins lost much of their animal wealth to drought and Ibn Saud’s raids, by the end of it, they lost it to the industrialization of sheep farming and modern farming techniques. Most devastating, however, was the shift in employment. Since the Mandate period, militarized welfare had been the backbone of economic transformation and the safety valve shielding these communities from socioeconomic change. With public-sector reforms and a reduction in state employment, this valve has been partly closed.

Climate impact is both an old and new factor for the inhabitants of Deir al-Kahf, one that is now increasingly tangible and measurable. The drought that occurred during the mid-1920s was crucial in shaping Bedouin trajectories. In discussing climate change with focus groups from villages in Deir al-Kahf, the authors concluded it is still not a central concern for the inhabitants, in comparison to water depletion, overgrazing, and especially unemployment.16 However, it is emerging as a key issue. Even optimistic forecasts suggest climate change will move from being a marginal factor to a central one among locals.

Rainfall and heat were the two factors most often linked to climate change in our focus groups. Rainfall’s growing unpredictability was a common complaint. A cultivator from Mafraq, who grew rain-fed wheat, recalled more reliable rains during the 1980s.17 Further east, in Deir al-Kahf, locals likewise described rainfall as more variable, pointing to vast areas of half-grown wheat.18 However, qualitative and quantitative data on rainfalls are not conclusive. Deir al-Kahf, where rainfall is between 50–100 mm annually, falls within an arid zone in which precipitation is typically erratic. A 2015 study of nine meteorological stations in the Badia confirmed highly fluctuating precipitation and a slight downtrend in rainfall compared to the 1970s: Safawi’s rainfall fell from just over 150 mm in 1977 to under 100 mm in 2004, while Mafraq’s declined from above 200 mm to about 160 mm for the same years. Yet the authors cautioned that “conclusions or quantifying the annual decreasing rate is not feasible due to the high fluctuation in the precipitation data.”

When looking at the Precipitation Concentration Index, which measures how evenly rainfall is distributed, a 2024 study across 164 stations in the Levant showed increasing rain concentration. This pattern was reflected in many parts of Jordan’s arid and semi-arid zones, but the station closest to Deir al-Kahf was in a band where rain has been irregular since the 1970s.

Unlike rainfall, data on rising temperatures in the Badia is both conclusive and alarming. Historical studies indicate that minimum annual temperatures rose in the last decade of the twentieth century. A study that looks at Jordan’s semi-arid and arid-areas in the north (from Mafraq to Riwaished) claimed that between 1980 and 2010 there was an average increase of 0.02–0.06°C per year. Projections for Jordan foresee an overall rise of temperature between 1.7 and 4.5°C by 2080 compared to pre-industrial levels, depending on climate scenario. Another study highlighted a growing number of hot days (above 35°C), with the Badia recording the highest counts nationwide. If those projections are remotely true, alongside current rates of water depletion, Deir al-Kahf and similar areas in Northern Badia will soon be unsuitable for cultivation or grazing.

The main coping strategy reported during the focus group discussions with both older and younger generations was migration westward in search of work.19 The city of Mafraq, some 80 kilometers to the west, has been a magnet for internal migration from Deir al-Kahf and elsewhere.20 A town of 6,000 people in 1950s, Mafraq grew to 58,000 in 2009 and 150,000 in 2022. After 2011, the main reason for its growth was cross-border migration, with an influx of Syrian refugees. However, a 2024 report notes that rural-urban migration has also been a factor in the city’s growth.

In terms of policy directions, the focus group discussions revealed three main lines of thinking pertaining to employment, the border economy, and environmental sustainability, offering fresh insights into the challenges Deir al-Kahf faces. Past policies have mainly been implemented through development work, capacity-building, nongovernmental organizations, and a reform of state regulations, for instance related to water use. However, after decades in which the benefits of development largely bypassed local communities as their socioeconomic situations deteriorated, it remains questionable who gains from more of the same.

In terms of state employment, open markets and merit-based competition for state jobs may sound appealing in theory. But for a community long dependent on secure state employment, they threaten the population’s main source of livelihood. As one senior elected official put it, young men from Northern Badia cannot compete for positions with those from Amman and Irbid.21 Therefore, some form of preferential treatment is necessary to level the playing field for residents of Deir al-Kahf and other marginalized communities in Northern Badia, whose access to education, capital, and basic services remains more limited than that of the inhabitants of major cities.

When it came to developing the local economy, the discussion was less about seeking more external aid or development projects and more about unlocking the potential of open borders. This was striking as the region’s political geography, especially borders and border crossings, reflect realities from the Mandate era. The borders the Mandatory powers imposed, whether with Syria or Saudi Arabia, divided communities that had been part of broader, continuous socioeconomic ecosystems, which remain embedded in the inhabitants’ mental geography. This has led them to think of alternative paths to revitalization, for example opening an official border crossing with Syria to reconnect local communities (the nearest crossing with Syria, Mafraq-Nassib, is 100 kilometers away), stimulate the local economy, and create an alternative route linking Syria and Saudi Arabia through Jordan in both directions. However, such thinking, as appealing and innovative as it might be, is unlikely to influence leaders in those countries.

A third policy pathway relates to sustainability. Research and focus group discussions reveal a prevailing pattern of agricultural development driven by outside investors who are focused on exports. They use land and water unsustainably, reflecting a short-term approach of exploiting resources intensively “while they last.” Such a rationale is amplifying environmental degradation, compounded by the fact that these activities increasingly fail to benefit local communities and are further exacerbated by climate change. Participants agreed that stronger regulations and oversight, the creation and maintenance of protected natural areas, and the management of water wells by public entities rather than private actors, for the benefit of entire communities, represent the most viable paths forward.

There is a dark irony at play. A century ago, settlement was the coping mechanism of the hitherto migratory Bedouin. They were faced with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and with it the loss of privileges, alongside a prolonged drought, the drawing of national borders, and the advance of state authority into the hinterland. Today, over a century later, migration away from the steppes has been their sedentary descendants’ coping strategy—the very steppes the Mandatory and post-Independence authorities sought to settle and cultivate.

Unfortunately, the odds are stacked against the local community. Jordan’s broader macroeconomic outlook is not very promising, compounded by Deir al-Kahf’s geographical isolation, the state’s diminished capacity to employ the population, mounting environmental challenges, and the looming threat of climate change, among others. What could potentially alter this trajectory is not more of the same, but a new policy approach. One such shift could derive from rethinking colonial-era borders and imagining ways to reconnect the economy of Northern Badia with that of Syria and Saudi Arabia, as it once was historically.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For more details regarding the license deed, please visit: CC BY 4.0 Deed | Attribution 4.0 International | Creative Commons.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Senior climate, finance, and mobility experts discuss how the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage could unlock financing for climate mobility.

Alejandro Martin Rodriguez

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

Is Morocco’s migration policy protecting Sub-Saharan African migrants or managing them for political and security ends? This article unpacks the gaps, the risks, and the paths toward real rights-based integration.

Soufiane Elgoumri

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright