Amid slow progress in climate multilateral negotiations, bilateral agreements can offer states a model for addressing the challenges of climate mobility.

Colorful houses and shops in the main street of Hillsborough, capital city of Carriacou, island of the Grenadine Islands, Grenada in the Caribbean Sea. (Photo by: Marica van der Meer/Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

How Caribbean States Became Climate Mobility Policy Innovators

Regional free movement agreements, like that of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, offer unique potential to address the human mobility challenges posed by the climate crisis.

In a world increasingly dominated by narratives about the importance of border security and restrictive migration policies, regional integration models such as that of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) offer a contrasting vision—one that views human mobility as a driver of economic growth, social development, and shared prosperity. Across many parts of the world, free movement agreements (FMAs) have become central to regional integration, enabling citizens to enter, work, and even settle in participating states. FMAs are provisions typically included in bilateral or multilateral economic trade and integration schemes, and over the past few decades, they have become standard policy tools through which states regulate cross-border movement with relative ease.

While the European Union’s Schengen Area is world-renowned and remains the most well-known example, FMAs are far from limited to Europe. Since the 1985 Schengen Agreement, regional and subregional integration initiatives containing free movement provisions have grown significantly, now involving over 110 states. The legal instruments underpinning such provisions have grown exponentially, and the rights they guarantee have also expanded accordingly. Today, FMAs are an important tool for enabling safe, orderly, and regular migration.

FMAs can not only play a role in regulating mobility and attaining regional integration but also hold promise as a policy response to climate mobility. They create structured mobility pathways that support economic integration, offer individuals greater agency and flexibility in deciding when and how to move, and can also address broader social challenges. Although not necessarily specifically designed to manage climate mobility, FMAs could allow people to relocate proactively—choosing to move before a climatic event or disaster forces them to do so. This aligns closely with the broader policy objectives identified in the global climate mobility debate: creating regular migration pathways that can facilitate mobility options, enabling those who wish to stay to do so in safety, and supporting pathways for those who need or choose to move to do so voluntarily, safely, orderly, and in a dignified manner.

For those reasons, a closer examination of FMAs is necessary, particularly of their potential to ease challenges faced by communities vulnerable to climate change. The OECS provides a good example. In a region heavily affected by climate impacts, this free movement regime can offer valuable lessons on how such systems operate, the innovative features they can include, and their importance in addressing climate mobility while supporting regional development and integration.

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States’ Free Movement Agreement

Migration has historically played a central role in the Caribbean, driven mainly by opportunities of employment or education and shaped in part by the migration policies of former colonial powers. These movements were usually perceived as temporary, with the expectation that migrants would eventually return. However, climate hazards are increasingly playing a role in people’s mobility choices, and recent geopolitical dynamics are making regional migration more relevant. Indeed, in an address to the nation on September 30, 2025, Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley said, “My friends, in a world where many are building walls, the Caribbean must build bridges. We must never become what we say we despise. We must not allow fear and insecurity to define us.”

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley said, “My friends, in a world where many are building walls, the Caribbean must build bridges. We must never become what we say we despise. We must not allow fear and insecurity to define us.”

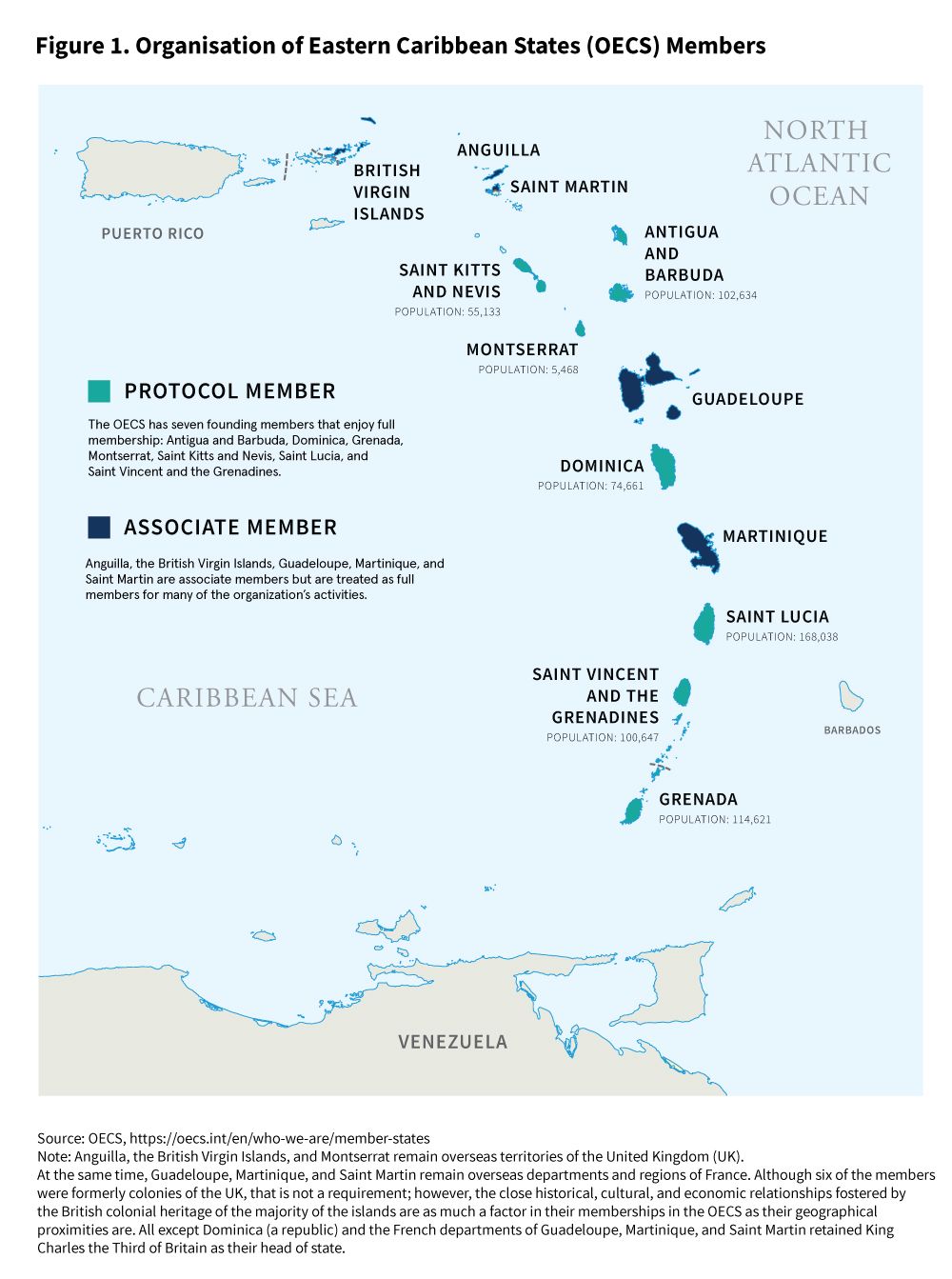

Against this backdrop, provisions that allow for regular and predictable intraregional mobility have become critical, including providing pathways for mobility for those whose choices may be increasingly shaped by environmental pressures. The Caribbean is a region historically connected through systems of economic integration and free trade, from the West Indies Federation in the 1950s to the Caribbean Free Trade Association in 19651 to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in 1973.2 In 1981, the OECS3 was established through the Treaty of Basseterre to increase cooperation and promote unity and solidarity among its members (see figure 1). Most OECS countries are also members of CARICOM, forming a subregional group within the broader Caribbean organization.

In 2010, the Revised Treaty of Basseterre established the Eastern Caribbean Economic Union to promote faster growth and development among member states and outlined a vision of deeper regional integration through the creation of a seamless common space. This enables the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people for all citizens of member states that are party to the economic union’s protocol (known as protocol members): Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.4 In total, over 600,000 people live in the territory of OECS protocol members. Citizens can access this free movement zone, with indefinite stay upon entry to other protocol members, facilitating the free mobility of people and labor, among other forms of movement.

The OECS free movement zone was not the first instance of a free movement policy for Caribbean states. The 2007 International Cricket Council Men’s Cricket World Cup was held in the West Indies, with matches played across different Caribbean islands. To facilitate ease of movement for visitors to the Cricket World Cup, a temporary single domestic space between ten countries was created to allow for freedom of movement between islands without the need for further border control between February and May 2007. After initial processing at their first port of entry in the region, visitors could access hassle-free movement without the need for further passport controls due to the implementation of an Advanced Passenger Information System. By the conclusion of the Cricket World Cup and the end of the single domestic space in May 2007, nearly 45,000 single-entry visas had been issued. Caribbean states were able to demonstrate the capacity to coordinate temporary free movement arrangements, and the popularity of such a program among citizens and visitors helped provide an important precedent for a permanent regime.

Building on this precedent, the OECS free movement regime formally allows citizens of protocol members to move freely to the territories of other protocol members, and it has become one of the foundational provisions of regional integration across the Eastern Caribbean.

Alongside access to the territories of protocol member states, the protocol of the Eastern Caribbean Economic Union also emphasizes the importance of securing for all citizens the rights linked to freedom of movement. This emphasis recognizes that mobility pathways alone are insufficient: Effective free movement requires guaranteed access to additional complementary rights such as healthcare and education.

It is evident that the legal entitlement to free movement must be supported by additional strategies to ensure its effective implementation in practice. In response, the OECS has progressively developed policies to address some of the obstacles and practical challenges that can hinder full operationalization of its free movement regime. For instance, in 2011, the OECS Authority—the governing body of the OECS with binding decisionmaking power5—granted indefinite entry and lifted work permit requirements for citizens of OECS protocol member states moving between protocol member states. To further facilitate hassle-free travel and easy integration across territories, additional supporting measures were introduced, including a provision allowing any national photo identity document to serve as a valid travel document and allowing driver’s licenses from one state to hold the same legal weight in other member states.

More significantly, the OECS policy on contingent rights was approved by the OECS Authority in November 2015. This effort aimed to ensure that all citizens of protocol member states and their families can access the rights and services that truly enable movement within the regional bloc, enabling them not only to live and work but also to access education, social security, healthcare, labor-market schemes, and social protections on equal terms with citizens of the host country (see box 1).

Box 1: Key Benefits of the Free Movement of Persons

The OECS highlights several benefits that the free movement of persons offers, including:

- “Indefinite Stay: Citizens of Protocol Member States and their family members (spouse and dependents) can live in any Protocol Member State indefinitely receiving an indefinite stay stamp upon arrival at the immigration desks (OECS Free Movement Indefinite Stay Stamp)

- “Hassle-free Travel: Citizens of Protocol Member States can travel within the ECEU with a valid government issued ID such as a driver’s license, national identification card and voter cards.

- “Mutual Recognition of Driver’s License: Citizens of Protocol Member States can drive within any Protocol Member State using a valid driver’s license issued by their home country.

- “No Work Permit: Citizens of Protocol Member States and their third-country spouse can work in any Protocol Member State without obtaining a work permit.

- “Social Security: Citizens of Protocol Member States and their spouse are entitled to the portability of social security benefits.

- “Contingent Rights: Citizens of Protocol Member States and their spouse and dependent(s) (including those of a third-country nationality) have equal access to numerous rights and freedoms with respect to employment, education, healthcare, and social protection within the host Protocol Member State when they move between Member States to reside and work. These benefits are fully expressed in the OECS Contingent Rights Policy.”

Relevance of OECS Free Movement for Climate Vulnerability

The importance of these contingent rights becomes even more apparent when viewed through the lens of the region’s acute climate vulnerability. As climate impacts intensify, the ability of OECS protocol member states’ citizens to move freely—and to access essential rights and services upon arrival—serves as a critical adaptation mechanism. Free movement provides a lawful and predictable pathway for those who may need to, or want to, relocate due to climate-related impacts, while ensuring continuity of their livelihoods, education, and social protections.6 The OECS regime can thus function as a climate-responsive framework for dignified mobility pathways for a highly climate-vulnerable region, even if it was not initially conceived as such.

The Caribbean’s inherent geographic and physical characteristics place it among the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions. Caribbean islands are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of sea-level rise, coastal erosion, flooding, and increasing extreme weather events, all of which threaten livelihoods, development, infrastructure, and communities. For example, the Bahamas, Dominica, and Montserrat are some of the most at-risk countries and territories to storm surges. These pressures have already translated into high levels of displacement: Between 2008 and 2018, more than 8.5 million displacements were recorded across twenty-one Caribbean countries. Notably, the Eastern Caribbean’s exposure to disasters is around twelve times higher than the global average, and three OECS protocol member states—Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, and Saint Kitts and Nevis—rank among the top ten countries with the highest ratios of expected annual displacement relative to population size in the world.

Despite the regionwide climate vulnerability, FMAs such as the OECS, with their emphasis on regional mobility and integration, still emerge as a highly relevant policy tool for addressing the complex realities of climate mobility. While facilitating internal movement within a climate-vulnerable region may seem counterintuitive, this approach offers distinct advantages. Climate impacts will often affect different islands at different times, and with varying intensity, so providing safe territory within the region will be essential even as the broader area faces elevated risk. Moreover, regional FMAs provide several key benefits for climate mobility.

First, free movement generally facilitates legal access to safe territory, creating regular and safe migration pathways. In the context of climate change, this directly responds to global calls to provide people with a safety net to ensure they have choices about how they respond to climate change. Such pathways also provide greater agency for migrants in deciding when and how to move. Proactive decisionmaking can be a key adaptation and risk management strategy, enhancing the benefits of migration and reducing associated risks. The freedom and flexibility inherent within FMAs enable people to move in anticipation of, during, or after sudden-onset events, as well as to preemptively and proactively migrate due to slow-onset events, both of which can be temporary or permanent. FMAs can also enable labor movements, which can generate remittances to support adaptation for communities left behind. Some studies have shown that FMAs contribute toward both regular and circular migration, allowing migrants to return home as desired, which can be a valuable tool during reconstruction in a postdisaster context. This fosters a continued connection to their countries of origin and thus can be a development strategy that supports both climate adaptation and remittance flows.

Second, the regional nature of the OECS agreement supports the research about climate mobility: It predominantly occurs internally, and when cross-border mobility does occur, it generally remains within the region. This is particularly true for small countries, especially those affected by sudden disasters, where cross-border migration may be the only option. FMAs are particularly well placed to facilitate this short-range, cross-border movement. Scholars such as Ama Francis have already highlighted the effectiveness of managing climate mobility at the regional level. For example, states are typically more receptive to negotiations when interacting with other states facing similar migration contexts. Regional management fosters an environment where shared interests and circumstances encourage collaborative solutions and mutual understanding. Finally, given that climate impacts differ across regions, regional responses to migration may also be more appropriate.

Third, as the OECS demonstrates, providing access not only to territory but also to education, employment, healthcare, and social security benefits allows free movement regimes to potentially evolve into frameworks that could realize the “human mobility with dignity” approach, which was included in the agreement between Australia and Tuvalu. This approach has also been highlighted by some scholars as a potential legal and policy framework to understand migration in the context of climate change through supporting the pursuit of life with dignity. With that, an FMA that includes other social rights could ensure that those who move into another participating state can live in dignity, thrive, and successfully integrate into their new host community. By empowering individuals who move, FMAs with social rights allow for mobility pathways to truly function as an adaptation and risk management strategy. Such policies are significant, as seen in our previous analysis on the Australia–Tuvalu Falepili Union.

Finally, climate change is rarely the sole driver of movement. Instead, it intersects with and intensifies other social, economic, cultural, and political factors that lead to displacement. Climate stressors cause environmental shifts that affect food security and livelihoods, and those who move may not consider climate change as the direct reason for leaving, making it challenging to disentangle climate change from other factors that drive migration. Considering the complexities of climate mobility and the varied drivers and resulting types of movement, FMAs are particularly useful as they provide benefits regardless of the rationale for mobility. FMAs do not respond to the root cause of migration but to its effects. They do not differentiate protection or policies based on why individuals choose to move—within the OECS, citizens of protocol member states would receive the same rights and benefits if they move due to climate-induced challenges as they would if they moved simply due to a desire to live and work in a different community. Without the need to differentiate benefits, such an arrangement neatly avoids the need to determine who qualifies as a “climate migrant,” a contested and often imprecise term given the complexities of the phenomenon and challenges of categorization.

The benefits of the OECS free movement regime are already evident. Research has shown that during the 2017 hurricane season,7 this regime enabled displaced people to find shelter and social protection in neighboring countries. Crucially, it:

- Ensured the right of entry for disaster-displaced persons into other islands, offering them safety and security during times of crisis

- Facilitated travel by waiving document requirements for those whose papers had been lost or damaged, taking into account the practical challenges that those moving in the context of disasters may face—an aspect that has been highlighted as a potential obstacle for many situations of climate displacement

- Provided opportunities for indefinite stays, allowing some individuals to permanently resettle

- Allowed access to foreign labor markets by the recognition of skills schemes from the country of origin and/or a waiver of the work permit requirements, enabling displaced persons to find formal employment

When Hurricane Maria devastated Dominica in 2017, damaging and destroying over 95 percent of housing on the island, citizens of Dominica were able to use the free movement regime to travel to Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, and Saint Lucia for shelter. Notably, even individuals whose identification documents were damaged were able to enter other OECS countries, and government officials were flexible in accepting alternative forms of identification, including evidence of family networks, to expedite travelers’ registrations and ensure rapid admissions. During Hurricane Maria, border management systems were not operational, which prevented exact reporting on the number of individuals from Dominica who utilized the FMA to leave the island. However, it is clear that many residents of Dominica benefited from the flexibility of this agreement in seeking safe refuge. While many returned after the disaster, some displaced individuals from Dominica chose to resettle permanently across other protocol member states, and the FMA allowed them to access new labor markets through mutual skills recognition schemes and no work permit requirements.

Recognizing that the region faces severe environmental and climate hazards that drive migration, displacement, planned relocation, and increased vulnerability for exposed populations, and in the spirit of regional integration and friendship, the OECS took another key step toward cementing regional cooperation regarding human mobility, but this time in direct relation to the impacts of climate change. The Ministerial Declaration on Migration, Environment and Climate Change was adopted in 2023 and proposed a comprehensive framework on human mobility in the context of climate change, including a commitment to “develop concrete solutions for persons crossing borders in the contexts of disasters, environmental degradation and climate change on the basis of national legislation and regional frameworks.” It also outlines actionable strategies, including the establishment of an OECS Inter-Ministerial Working Group on Climate Change, Environment and Migration and the development of a plan of action for implementing the declaration. Figure 2 summarizes the key policy developments that this article has analyzed.

Additional Policy Innovations Offered by the OECS Free Movement Agreement

In a world that appears increasingly focused on border security and hostile toward migrants of all kinds, bilateral and regional agreements offer a different narrative, one based on embracing the freedom of movement of people. The OECS model of regional integration provides a new way to address modern development challenges, viewing human mobility and regional cooperation as opportunities for economic growth and shared prosperity. Likely because of their shared geography, history, culture, and small-scale economies, OECS countries aimed for a unified economic goal by establishing their economic union, with a vision centered on the region’s people and their quality of life, which has resulted in a greater appreciation for people’s contributions to development, through labor and otherwise. By focusing on people’s contributions, the OECS framework mirrors global evidence that well-managed migration can stimulate the economy and strengthen labor markets. Not only would such a strategy build individual and community resilience, but it could also support intraregional growth. Experiences from other FMAs reinforce this: Within the European Schengen region, for example, free movement is understood to generally lead to higher employment, productivity, and income, and to have a positive effect on the flow of taxes and social contributions.

Additionally, rather than solely aiming to extract the financial benefits of the economic union, the OECS has focused on fostering a shared identity and the well-being of all OECS citizens and their families. It is not surprising, then, that an effort such as the contingent rights policy, which has a people-centered approach at its core and aims to guarantee the portability of rights linked to the free movement regime, was grounded in three fundamental principles:

- Maintaining the quality of life for OECS citizens exercising their right to freedom of movement within the economic union

- Protecting the unity of the family and the right to reside together

- Upholding a rights-based approach to human and social development in accordance with international best practices

Through this policy, the OECS cements its aim of providing more than simply legal access to foreign territory. In addition, it creates a pathway that tackles practical barriers, addresses broader social needs, considers family unity, and promotes long-term settlement solutions for those who want or need to move. This approach can change mobility from a short-term plan into a sustainable choice for long-term settlement. When combined, all the instruments that conform to the OECS free movement regime form a comprehensive system that benefits many OECS citizens and their families, allowing them to enjoy the portability of social and economic rights when moving within the region.

Furthermore, some scholars argue that FMAs provide a more politically feasible approach to address climate mobility compared to pursuing a global multilateral agreement. This increased feasibility stems from the fact that neighboring states—which often share similar concerns and priorities—can reach a regional consensus more quickly than a complex area of global negotiations. Regional agreements are also generally easier to finalize because they involve fewer countries, reducing the complexity of international negotiations. Another noteworthy feature of regional FMAs is their ability to adapt to changing circumstances and environments. In practice, member states can unilaterally expand the scope of rights or add new categories based on humanitarian grounds.8 This was evident in Argentina in 2022, when the government issued a new legal provision to facilitate additional entry into the territory for nationals of neighboring countries when fleeing sudden-onset disasters. Under the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) and its Residence Agreements, Argentina’s neighbors already benefit from free movement. This measure, therefore, serves as a supplementary provision that provides greater safeguards to people who face increased vulnerability. This example clearly shows how existing FMAs can be expanded to address climate mobility.

Developments in the Caribbean region show a similar trajectory. CARICOM has long considered the idea of full free movement among its member states. Although this goal has been discussed among its members, its realization has been limited, focusing mainly on easing the mobility of skilled labor.9 This changed in October 2025, when CARICOM members Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines launched the implementation of a full free movement regime. This agreement allows nationals from those four countries to reside, work, and remain indefinitely in the host country with the right to access healthcare and education. According to Mottley, “a country like Barbados needed the regional integration project in order to do better for [its] people.” Safe and regular migration was understood to be key for supporting Barbadian national development goals and resilience. Many CARICOM states are experiencing labor shortages in key sectors, and freedom of movement has been seen as a way to match skills with opportunities and support economic growth. There are now expectations that several other countries are in a wait-and-see mode and that many more will join.

Limitations and Challenges of Free Movement Agreements

Some academics caution against assuming that FMAs alone will resolve climate mobility challenges, and they are likely correct. More commitment from participating states and extra external support are needed to address the main challenges. For instance, while FMAs offer important opportunities for those who move due to disasters and/or climate change, key gaps remain in ensuring that affected communities can access these mechanisms in practice. Key challenges include the ability of participating states to suspend the agreements in situations of disaster; exclusion of stateless people; limited protections of rights; lack of protections against forcible return; and lack of pathways to permanent residence for disaster-displaced people.10 Furthermore, FMAs generally accord rights and benefits for nationals of participating states, but climate mobility will also involve refugees, stateless people, and third-country nationals who may fall outside the scope of such agreements. Safeguards for such groups will be necessary to ensure that mobility frameworks can benefit all.

The OECS FMA has laid out a comprehensive regime, enabling many citizens to benefit from the portability of social and economic rights. However, as in other examples analyzed across different parts of the world, implementation across the region has been inconsistent. Differences in domestic legislation and administrative practices have caused variations in how these rights are realized across member states. To address these issues, an OECS working group in May 2024 assigned the OECS Commission to develop a comprehensive model legislation, resulting in the OECS Contingent Rights Model Bill, which considers the application of contingent rights for OECS citizens, their spouses, and dependents within disaster scenarios, demonstrating member states’ recognition of the impact of climate disasters on the region. Because the early legal instruments that set out the free movement regime in the OECS region did not explicitly reference human mobility in the context of climate change, the OECS could utilize its Contingent Rights Model Bill as a key opportunity to specifically include additional considerations and protections tailored to climate change and related disasters, thereby clarifying and reaffirming its applicability in the context of free movement.

In fact, other FMAs are more explicit about this, such as Eastern Africa’s Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), which includes countries in the Horn of Africa and neighboring regions. Here, environmental stressors are understood to be a key factor driving human mobility in the region. The 2020 IGAD Protocol on Free Movement of Persons included provisions to establish a legal basis for the movement of citizens in anticipation of, during, or in the aftermath of an environmental disaster. There are a few relevant provisions in this regard. First, IGAD’s protocol grants residents of border communities straightforward access to mobility. This access allows individuals living in these areas to use mobility as a tool for adapting to climate-related challenges. A second relevant provision permits citizens from other member states to enter the territory when moving in anticipation of, during, or after a disaster. This measure ensures that those affected by disasters can seek safety without unnecessary barriers, especially when their circumstances require them to cross borders. Finally, it facilitates the extension of stays or the exercise of other rights for citizens of member states affected by a disaster. This is especially important in situations where returning to a home country is not possible or reasonable.

During moments of sudden-onset natural disasters, FMAs can allow for anticipatory movement, offering the opportunity for ease of relocation before and during a disaster. However, regional FMAs like the OECS present a challenge if and when regional vulnerabilities increase. The Caribbean as a region is highly vulnerable to climate shocks, including slow-onset climate processes. These events such as sea-level rise, salinization, increased drought, and coastal erosion produce adverse effects and degrade terrestrial and marine ecosystems in ways that are often less understood. Such changes can become drivers of migration as livelihoods become unsustainable. In contexts where the entire region faces similar push factors that can drive a desire to relocate, regional FMAs may fail to provide individuals with the same level of supportive policy response. This is where the combination of policy tools—including the FMA regime, the Ministerial Declaration on Migration, Environment and Climate Change, as well as strategies and initiatives to promote climate and disaster resilience such as the OECS Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy and Disaster Preparedness and Response Plans—will be needed to craft a regional climate mobility policy response that takes into account the various impacts, drivers, resulting movements, and related vulnerabilities.

Additionally, while FMAs offer a potential pathway for facilitating climate mobility, more must be done to ensure that free movement is not just accessible in policy but also in practice for affected communities. Within the OECS, similar concerns emerge. These include resource constraints preventing the operationalization of rights under the agreement, limited data-sharing mechanisms, and the need to ensure that the FMA can coexist and interact with existing short-term disaster response mechanisms, such as the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. Similarly, citizens of OECS protocol member states also enjoy privileges under the CARICOM Free Movement of Skills regime. A clearer articulation of how both regimes interact, and how individuals can exercise rights under each, will be essential to ensure policy coherence and avoid duplication. Increased alignment between OECS and CARICOM provisions could create a stronger, layered mobility system that responds more effectively to climate challenges.

Looking Forward

Most human mobility will remain internal or regional. Many regions and subregions have existing FMAs in place—over 110 states currently participate in such arrangements. Although few include explicit climate considerations, FMAs are a high-potential option for governance responses that support climate-vulnerable populations. They can provide legal access to another territory, rights in a foreign country, lasting solutions elsewhere, circular movement, and proactive, preemptive mobility.

However, as the OECS case study illustrates, accelerating regional integration during periods of economic crises, natural disasters, and public health challenges cannot occur without the necessary resources. Strengthening the capacity of participating OECS states will require greater technical and financial support to ensure coordination, effective implementation, and policy coherence across the region.

The success of FMAs requires effective free movement to occur in practice. This requires the implementation of contingent rights that support broader social and economic integration. One main concern that has been highlighted is that implementing FMAs is often challenging and requires significant resources. Most regional economic communities interested in promoting free movement lack the capacity, whether in financial resources or technical support, to ensure coordination, effective implementation, and policy coherence of the FMAs. For these efforts to be truly effective, they will need technical and financial support from various external actors, including development financial institutions, bilateral donors, philanthropy, and dedicated climate funds. These sources can help pilot different aspects of free movement regimes that can address climate mobility considerations, which can then be expanded if successful.

Regional tools such as the OECS will be key instruments that can be adapted to address the challenges of climate mobility, as they have greater flexibility to create proactive pathways to safe and dignified movement for individuals who may desire to move. FMAs are far from a magic bullet for addressing climate mobility; however, with the right support, they are a promising instrument for mobility policy, with the capacity for sustained innovation to address the multifaceted challenges of climate mobility. The OECS framework illustrates how regional agreements to design flexible systems of mobility can serve as a forward-looking strategy for resilience amid climate change.

Ultimately, the OECS FMA offers a compelling vision for climate mobility grounded in the benefits of human mobility and regional integration. By providing individuals with safe and dignified mobility pathways, such regimes can support individuals in determining whether, where, and when to move. Their regional character may also widen the political horizon of possibility, allowing for cooperation that remains difficult at the global level. Yet, the success of such regimes depends on regional implementation capacity. If states are able to invest in governance mechanisms that build out their institutional capacity and regulatory interoperability to support equitable access to rights in practice and not just in principle, these agreements can offer a forward-looking instrument that supports proactive climate mobility—one that anticipates movement and expands individual agency.

About the Authors

Nonresident Scholar, Carnegie California; Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics Program

Liliana Gamboa is a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Carnegie California and in the Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics Program. Liliana most recently was program manager at the Open Society Foundations. Liliana has over fifteen years of experience working in the human rights field, in work that ranges from designing and implementing anti-discrimination projects in Dominican Republic, Colombia, and Chile to climate justice work in the Caribbean.

Debbra Goh

Research Assistant, Sustainability, Climate and Geopolitics Program

Debbra Goh is a research assistant in the Sustainability, Climate and Geopolitics Program.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Resetting Cyber Relations with the United StatesArticle

For years, the United States anchored global cyber diplomacy. As Washington rethinks its leadership role, the launch of the UN’s Cyber Global Mechanism may test how allies adjust their engagement.

Patryk Pawlak, Chris Painter

- China’s AI-Empowered Censorship: Strengths and LimitationsArticle

Censorship in China spans the public and private domains and is now enabled by powerful AI systems.

Nathan Law

- Why Are China and Russia Not Rushing to Help Iran?Commentary

Most of Moscow’s military resources are tied up in Ukraine, while Beijing’s foreign policy prioritizes economic ties and avoids direct conflict.

Alexander Gabuev, Temur Umarov

- Georgia’s Fall From U.S. Favor Heralds South Caucasus RealignmentCommentary

With the White House only interested in economic dealmaking, Georgia finds itself eclipsed by what Armenia and Azerbaijan can offer.

Bashir Kitachaev

- Lessons Learned from the Biden Administration’s Initial Efforts on Climate MigrationArticle

In 2021, the U.S. government began to consider how to address climate migration. The outcomes of that process offer useful takeaways for other governments.

Jennifer DeCesaro