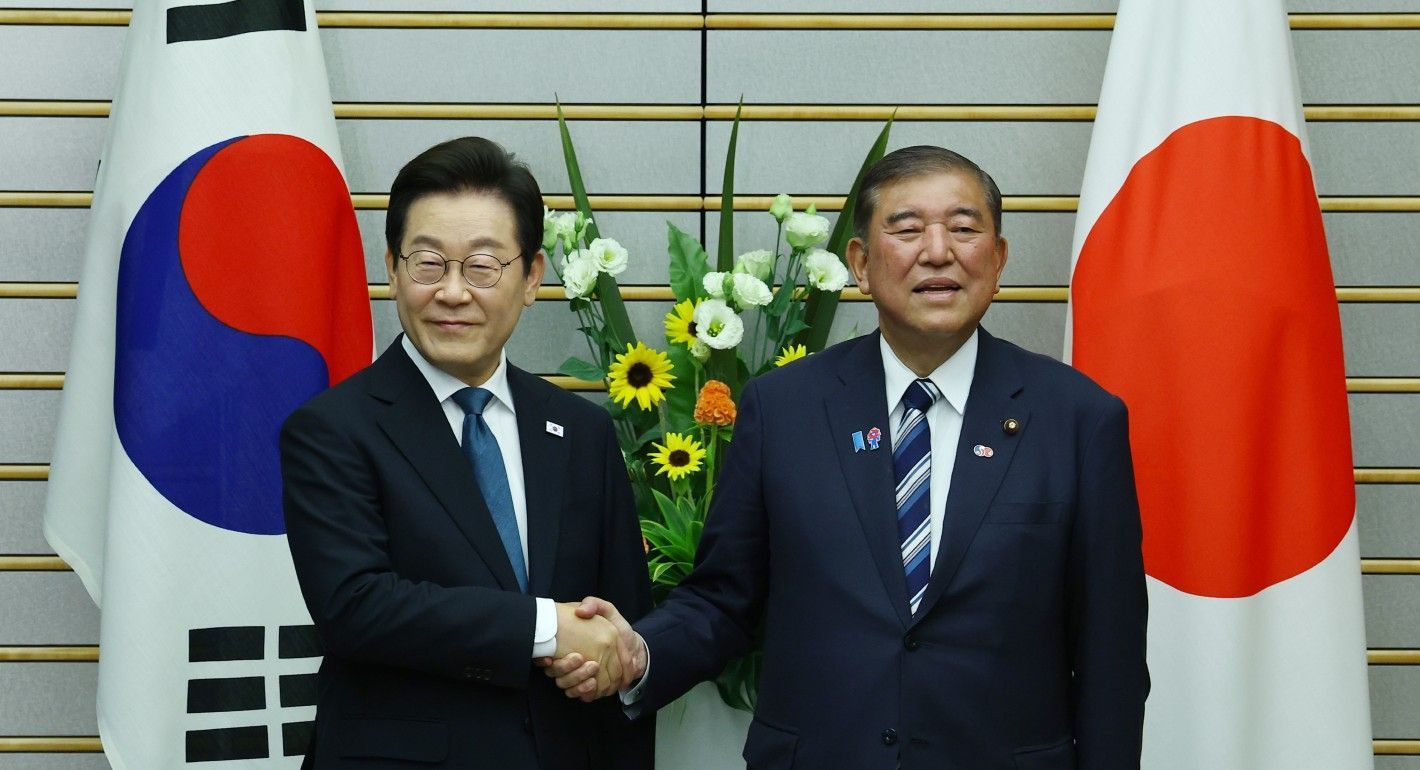

Even before he met with U.S. President Donald Trump in Washington, South Korea’s new progressive president had already taken a momentous diplomatic step. Lee Jae Myung’s first overseas trip wasn’t to Washington, its seventy-one-year treaty ally and typical first stop for recently inaugurated South Korean leaders. It also wasn’t to Beijing, its largest trading partner. It was to Tokyo, for a meeting with his Japanese counterpart, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba.

For casual observers of East Asian affairs, that choice might seem mundane. As neighbors, Japan and South Korea both rank among the world’s top economies (fifth and thirteenth, respectively), boast robust democratic institutions, and wield significant cultural soft power globally—from Japan’s Cool Japan phenomenon to the Korean Wave sweeping international audiences.

Yet Korea-Japan relations remain haunted by imperial history. Japan’s colonial rule from 1910 to 1945 left deep wounds: Forced labor, sexual slavery, and systematic suppression of Korean culture remain politically salient issues. These grievances have traditionally been mobilized by Korea’s progressive left, particularly when out of power—from intelligence-sharing disputes to protests over living history issues to trade disputes.

However, as I wrote in May, South Korean progressive foreign policy has been showing a shift toward more pragmatic, security-conscious positions driven by structural constraints that have fundamentally narrowed policy options across the political spectrum. Against this backdrop, the Lee administration’s substantive approach to Japan ties—not merely its diplomatic timing—represents the clearest evidence yet of this transformation.

The Outcomes

Press reports from both countries have noted the leaders’ emphasis on tackling common economic and security challenges rather than competing over historical narratives. Several outcomes suggest three significant shifts in progressive Korean foreign policy thinking as epitomized by the politicking of Lee.

First, the two leaders emphasized direct Korea-Japan cooperation across multiple domains, not merely trilateral coordination with Washington. This represents a maturation beyond the traditional hub-and-spoke alliance model, where the U.S. bridged regional partners. Building on the 2023 Camp David summit’s institutional foundations, Seoul and Tokyo are now strengthening bilateral coordination mechanisms. This is particularly significant as Trump’s transactional approaches and economic threats to allies raises questions about American commitment to alliance management.

Second and most notably, Lee framed North Korea’s nuclear program as requiring coordinated responses with Japan—a marked contrast to progressive predecessors who preferred to go it alone. This reflects a broader transformation where North Korea’s nuclear advancement and isolationism have fundamentally altered progressive calculations about the feasibility of engagement. North Korea’s recent constitutional changes removing references to peaceful unification and designating South Korea as a hostile state have undermined the ethnic solidarity assumptions that previously guided progressive engagement policies.

Finally, Lee and Ishiba focused on common domestic pressures: demographic decline, energy transitions, AI development, and rural revitalization. The emphasis on hydrogen cooperation, artificial intelligence, and advanced technology partnerships reflects progressive foreign policy’s growing focus on economic security and technological sovereignty alongside traditional security goals.

The Transformation Behind the Summit

This historic diplomatic choice—the first time a Korean president has selected Japan for a first foreign visit since normalization in 1965—reflects how structural realities have reshaped progressive calculations despite ideological resistance. Certainly, elements of Korea’s left remain skeptical of deepening Japan ties, with the progressive Hankyoreh editorial board warning postvisit that Lee “conceded too much” on history and North Korea policy. The strategic, political, and economic pressures Lee faces made Tokyo the logical destination for his diplomatic debut.

Over the past few years, three interconnected factors have fundamentally altered how Korean progressives view Japan and foreign policy more broadly, creating the conditions that put this summit on the books. But substance, not just symbolic timing, reveals the depth of this transformation.

First, geopolitics have dramatically narrowed policy options for Seoul vis-à-vis its neighbors. Intensifying U.S.-China competition, North Korea’s nuclear maturity, and China’s economic coercion following against Seoul’s national defense decisions have collectively limited South Korea’s foreign policy calculus, regardless of which party holds power. External constraints, rather than purely ideological preferences over historical narratives, now drive strategic choices.

Second, the lagging national economy, combined with the anticipated blowback from Trump’s unilateral tariffs, has sharpened public demands for a foreign policy that delivers concrete benefits on technological competitiveness, energy security, and economic opportunity at home. South Korean voters increasingly frame foreign policy around material well-being rather than historical justice, creating space for cooperation that promises to improve their daily livelihood.

Third, recent survey data reveals a dramatic transformation in South Korean attitudes toward international partnerships. Favorable views of Japan have surged from 28.9 percent in 2023 to 63.3 percent in 2025, with the East Asia Institute’s June 2025 survey marking a historic first—favorable views of Japan and its prime minister exceeded unfavorable ones. Most significantly, South Koreans now prioritize cooperation with Japan in areas such as technology, security, and environment (49.6 percent) over resolving historical issues (31.5 percent)—a striking reversal from 2021 when historical grievances dominated policy priorities.

As I wrote in Asia Policy earlier this year, the combination of narrowing policy space and shifting domestic preferences has produced the more pragmatic, security-conscious approach to Japan relations that’s now visible in the Lee-Ishiba meeting. Although political will remains necessary for bilateral progress, it’s rarely sufficient without favorable structural conditions—and those conditions have finally aligned under Lee’s presidency.

What This Means for Regional Order

Lee’s diplomacy with Tokyo represents more than bilateral fence-mending. It signals how middle powers navigate great power competition through strategic diversification. For Washington, this creates both opportunity and complexity. A pragmatic and progressive Seoul offers more predictable partnership but may prove less deferential to U.S. preferences, particularly as Trump’s transactional approach raises questions about alliance reliability.

Meanwhile, Beijing may be staring down a strategic setback. The Korea-Japan technology cooperation Lee emphasized directly counters Chinese efforts to fragment critical supply chains in securitized tech sectors. But looking with a wider aperture, this might be of China’s own making: Beijing’s economic coercive tactics against Korea likely have inadvertently accelerated the very coordination it sought to prevent.

Most significantly, Lee’s approach offers a template for democratic resilience amid polarization. By grounding foreign policy in material interests rather than ideological positioning, mature democracies can maintain strategic coherence despite domestic divisions—a crucial capability as authoritarian leaders exploit democratic discord.

The Durability Question

Past Korea-Japan rapprochements have collapsed when domestic politics overwhelmed strategic logic. Several factors suggest greater staying power this time. First, the relative weakness of the conservative opposition following former president Yoon Suk Yeol’s martial law declaration and eventual impeachment limits its ability to counter any objection to Lee’s foreign policy direction. In the most recent Gallup Korea survey, public approval rating of the ruling Democratic Party stood at 44 percent, against a paltry 25 percent favor for the conservative People’s Power Party.

Second, the track record suggests that Japan relations are primarily weaponized by progressives when they’re in opposition, not by conservatives. The left has traditionally mobilized historical grievances to challenge conservative governments’ Japan policies, while conservatives lack both the ideological motivation and grassroots infrastructure to orchestrate sustained anti-Japan campaigns against progressive governments.

Most significantly, Lee has strategically redefined his political base from the far-left coalition that initially propelled his rise—built on redistributive policies and anti-imperialist rhetoric—toward a broader centrist tent. This repositioning removes the wind from the sails of stoking anti-Japanese sentiment for short-term political gain, as Lee no longer depends on the activist base that would demand such tactics.

However, this transformation raises a critical sustainability question: Will Lee maintain his pragmatic Japan approach when his approval ratings inevitably dip? Previous progressive presidents have reinvigorated historical grievance politics when facing domestic pressure. Lee’s true test will come not during his current honeymoon period, but when political expedience might tempt a return to the anti-Japanese mobilization playbook that once served his political ascent.

For a region historically defined by division, the Northeast Asian order could be reshaped by Lee’s transformation of progressive foreign policy. The question isn’t whether this shift makes strategic sense—structural realities have settled that debate. It’s whether democratic leaders can sustain pragmatic cooperation long enough to build irreversible momentum.

Emissary

The latest from Carnegie scholars on the world’s most pressing challenges, delivered to your inbox.