Registration

You will receive an email confirming your registration.

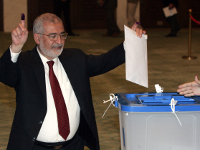

On March 7, Iraqis went to the polls to vote in their second free parliamentary elections since the writing of the Iraqi constitution. The months leading up to the election were tumultuous, particularly the debate surrounding candidates who had been members of the Baath party during Saddam Hussein’s era., Iraq’s political leaders now face the difficult challenge of forming a government.

Carnegie hosted a discussion of the elections and their aftermath with Saifaldin D. Abdul-Rahman, former advisor to Iraqi Vice President Tareq al-Hashemi, Brian Katulis of the Center for American Progress, and Carnegie’s Marina Ottaway. Carnegie’s Michele Dunne moderated the event.

The Significance of the Elections

Both Abdul-Rahman and Ottaway made it clear from the start that they do not believe Iraq’s elections should be understood as a ‘watershed moment.’ Abdul-Rahman suggested that the elections were better understood as “a blip in a longer process.” The candidates and parties involved, and some of the issues involved, do not significantly differ from those involved in the 2005 elections.

Abdul-Rahman disagreed with the general claim by the Western media that Iraq has moved away from sectarianism. Preliminary election results show the strengths and weaknesses of the various alliances are still based on geographic locales defined by sectarian majorities.

Ottaway agreed with Abdul-Rahman about the elections, offering her interpretation that the elections were best understood as a “re-kneading of dough.” The actors are the same, only the shape is being changed and reworked,

Election Results

Results so far indicate a near parity in the number of seats won by Maliki’s State of Law Coalition and Allawi’s Iraqi National Movement. Discussing these close results, Ottaway and Abdul-Rahman agreed that the formation of a governing alliance and the apportionment of major posts will be decided through long, drawn-out backroom negotiations. Election results reveal who will participate in the negotiations, but much remains to be determined in the formation of a governing coalition:

- The Kurds: The panelists agreed that no government could be created without an alliance with the Kurds. This, according to Abdul-Rahman, makes it very difficult for Allawi, whose allies won a number of seats based on pro-Arab, anti-Kurdish agendas.

- Out-of-Country Votes: Ottaway pointed out that the complete results, including those of out-of-country voting, remained to be tabulated. She pointed out that the out-of-country votes would probably benefit Allawi and his coalition.

- Seat Thresholds: Abdul-Rahman explained that seats in Iraqi Parliament are allocated by a ‘seat threshold,’ which is determined by dividing the number of seats a province has in Parliament by the number of votes cast in that province. As a result, a party that is two votes shy of the threshold could be denied any seat in Parliament, and a party that has two votes over the threshold could get a seat. Parties that exceed the seat threshold can then choose who is given extra seats, which involves a great deal of political negotiations.

The Months to Come

In the aftermath of the elections, parties that have won seats will have to forge alliances and coalitions in order to create a government. Ottaway suggested that the reemergence of an alliance between the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), Maliki’s State of Law Coalition, the Kurdish Alliance, and the religious Sunni Accord Front is the easiest possibility for government formation. Nonetheless, Ottaway asserted that such an alliance would be weak and would not be seen as representative by many, particularly Sunnis.

None of the panelists expressed optimism for the possible governing coalitions that might be formed. Ottaway described all likely coalitions as vulnerable. Current alliances may not survive the government formation process:

- One alliance that is particularly susceptible to disintegration is the Iraqi National Movement which joins Allawi, who has played the role of a conciliator, and Mutlaq, who is an ardent Arab/Sunni nationalist.

- Another potential weakness is the alliance between the Sadrists and the rest of the actors in the Iraqi National Alliance. If the Sadrists end up breaking away from the Iraqi National Alliance, they would take the majority of the coalition’s seats with them.

Abdul-Rahman concurred with Ottaway’s assessment, predicting that whatever the eventual outcome of the political negotiations, the Iraqi government will continue to be headed by a weak governing coalition.

Abdul-Rahman pointed out the possibility that a number of parties that will receive parliamentary seats, such as the Sadrists, will not get positions in government because they are unlikely to ally with any of the possible governing coalitions. Such complications only add to the likelihood that government formation will be a long process, with the potential for problems to develop on the security front.

Iraq and its Neighbors

Ottaway suggested that Allawi would have an easier time bringing Iraq back into the good graces of its neighbors than a government headed by Maliki. Allawi made a point of visiting a number of Arab capitals during his campaign, and he was relatively warmly received.

In addition, she stated that no Iraqi government coalition would take an anti-Iranian stance, regardless of its makeup. Iran has invested in relations with the various political players in Iraq.

U.S.-Iraqi Relations

Katulis argued that Iraq is still a “salvage operation” for the United States, where the U.S. government is still trying to make up for past mistakes. Correcting those mistakes will require continued U.S. engagement. The United States, he asserted, must play a supporting role in Iraq and live up to its commitments to the nation.

- Security Agreement and the Strategic Framework Agreement: Katulis urged the current administration to live up to its commitments in the Security Agreement and the Strategic Framework Agreement. The Security Agreement must be implemented by fall 2010, and that the implementation must be accomplished in coordination with the Iraqis.

- Smart Power: Katulis pushed for the implementation of smart power in Iraq, to help the country be stable and independent. To accomplish this, the United States would have to draw down militarily and increase civilian support, economic support, and institution building, in order to be more effective in improving the lives of Iraqis.

- Regional Strategy: Most importantly, Katulis expressed the need for a regional strategy. The invasion of Iraq brought the U.S. Middle East policy into what Katulis called ‘strategic incoherence.’ Both Katulis and Abdul-Rahman agreed that the United States needs to figure out how Iraq fits into U.S. long-term regional strategy.

Abdul-Rahman concluded by reminding the audience that the economic prospects for Iraq are significant, particularly in regards to Iraq’s oil reserves. Investment from other Arab countries is already on the rise. Whoever heads the new government will likely see increased interest and engagement from other regional players, who have been hesitant to deal with Iraq until now..