Minxin Pei

{

"authors": [

"Minxin Pei"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"East Asia",

"China"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy",

"Economy",

"Security",

"Military"

]

}

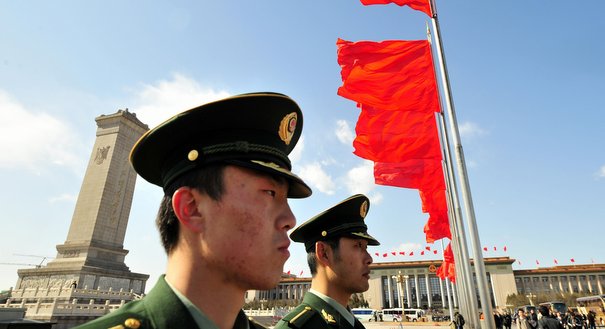

Source: Getty

How Beijing Kept Its Grip on Power

When the Chinese Communist party toasts its post-Tiananmen success, it should be under no illusion that the good times are here to stay.

Source: Financial Times

Twenty years later, things could hardly be more different. China is riding high as a new economic and geopolitical giant. The party’s rule has never felt more secure.

Chinese leaders appear to believe that they have discovered the magic formula for political survival: a one-party regime that embraces capitalism and globalisation. Abroad, the party’s success raises fears that it has established a viable new model for autocratic rule.

As the world commemorates the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen tragedy, it is time to reflect on how the party has held on to power against seemingly impossible odds and whether the strategy it has pursued since Tiananmen will continue to sustain its political monopoly.

Clearly, the most important explanation for the party’s apparent resilience is its ability to deliver consistently high growth. However, largely through trial and error, the party has also developed a complementary and quite sophisticated political strategy to strengthen its power base.

A lesson taken from the Tiananmen debacle by the party’s leaders is that elite unity is critical to its survival. The political necessity of launching China’s economic reforms in the late 1970s required the party to form a grand alliance of liberals, technocrats and conservatives. But the liberals and the conservatives constantly clashed during the 1980s, over both the speed and direction of reform.

Disunity at the top sent out mixed signals to Chinese society and, during Tiananmen, paralysed the decision-making process. After Tiananmen, the party purged liberals from its top echelon and formed a technocratic/conservative coalition that has unleashed capitalism but suppressed democracy.

An additional lesson learnt from the party’s near-death experience in Tiananmen was that it must co-opt social elites to expand its base. The pro-democracy movement was led and organised by China’s intelligentsia and college students. The most effective strategy for preventing another Tiananmen, the party apparently reasoned, was to win over elite elements from Chinese society, thus depriving potential opposition of leadership and organisational capacity.

So in the post-Tiananmen era, the party courted the intelligentsia, professionals and entrepreneurs, showering them with perks and political status. The strategy has been so successful that today’s party consists mostly of well-educated bureaucrats, professionals and intellectuals.

Of course, when it comes to those daring to challenge its rule, the party is ruthless. But even in applying its repressive instruments it has learnt how to use them more efficiently. It targets a relatively small group of dissidents but no longer interferes with ordinary people’s private lives. In today’s China, open dissent is stifled but personal freedom flourishes.

On the surface, the collapse of the Soviet Union reduced China’s strategic value to the west. But after overcoming its initial shock, the party adroitly exploited the situation by using the turmoil in the former Soviet bloc to instil in the Chinese public the fear that any political change would bring national calamity. Rising Chinese nationalism, stoked by official propaganda, allowed the party to burnish its image as the defender of China’s national honour.

The wave of globalisation that followed the cold war offered another golden opportunity. Capitalising on the lure of the Chinese market, the party befriended the western business community. In turn, western businessmen found a natural partner in the Chinese Communist party, its name notwithstanding.

With any self-respecting multinational rushing into the Middle Kingdom, those who refused to recognise the new reality risked being outcompeted. In China, they also found undreamt-of freedom in doing business: no demanding labour unions or strict environmental standards. Wittingly or otherwise, western business has become the most powerful advocate for engagement with China. Its endorsement, along with the pragmatic policy pursued by western governments, has lent a legitimising gloss to the party’s rule.

Ironically, this political strategy has worked so well that the party is now paying a price for its success. With the technocratic/conservative alliance at the top and the coalition of bureaucrats, professionals, intelligentsia and private businessmen in the middle, the party has evolved into a self-serving elite. Conspicuously, it has no base among the masses.

There is already a backlash against the party’s post-Tiananmen pro-elite policies, which have resulted in inadequate social services, rising inequality and growing tensions between the state and society. Externally, the alliance with western business is also fraying, as China’s bureaucratic capitalism – anchored by state-owned monopolies and mercantilist trade policies – begins to alienate the party’s (genuinely) capitalist friends.

So when the Chinese Communist party toasts its post-Tiananmen success, it should be under no illusion that the good times are here to stay.

About the Author

Former Adjunct Senior Associate, Asia Program

Pei is Tom and Margot Pritzker ‘72 Professor of Government and the director of the Keck Center for International and Strategic Studies at Claremont McKenna College.

- How China Can Avoid the Next ConflictIn The Media

- Small ChangeIn The Media

Minxin Pei

Recent Work

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Unintended Consequences of German DeterrenceResearch

Germany's sometimes ambiguous nuclear policy advocates nuclear weapons for deterrence purposes but at the same time adheres to non-proliferation. This dichotomy can turn into a formidable dilemma and increase proliferation pressures in Berlin once no nuclear protector is around anymore, a scenario that has become more realistic in recent years.

Ulrich Kühn

- The Iran War’s Dangerous Fallout for EuropeCommentary

The drone strike on the British air base in Akrotiri brings Europe’s proximity to the conflict in Iran into sharp relief. In the fog of war, old tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean risk being reignited, and regional stakeholders must avoid escalation.

Marc Pierini

- When Do Mass Protests Topple Autocrats?Commentary

The recent record of citizen uprisings in autocracies spells caution for the hope that a new wave of Iranian protests may break the regime’s hold on power.

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Resetting Cyber Relations with the United StatesArticle

For years, the United States anchored global cyber diplomacy. As Washington rethinks its leadership role, the launch of the UN’s Cyber Global Mechanism may test how allies adjust their engagement.

Patryk Pawlak, Chris Painter