Source: International Monetary Fund's Finance and Development

As Arab countries face dire economic challenges, it is easy to forget that not long ago many of them were in a similar—or worse—position. If the region is to successfully tackle unemployment, encourage foreign investment, and foster economic growth, leaders must take lessons from the recent past.

These lessons offer five rules for success. Economic reforms cannot succeed in isolation, but must go hand in hand with political transitions. They must benefit all segments of society and have buy-in from everyone. They should be quantifiable based on a clear goal. Finally, plans for economic reform must be communicated effectively.

Nothing new under the sun

This is not the first major economic test for Arab countries in transition, nor the first appearance of crucial economic reforms.

Egypt and Jordan, for example, dealt with similar economic crises 20 years ago that were worse in certain respects than those they face today. In the late 1980s, the budget deficit in Egypt was almost 20 percent of GDP and the inflation rate was also 20 percent—both twice what they are today. Egypt’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 76.5 percent, almost identical to today’s 76.4 percent. And Jordan had a staggering debt ratio of 133 percent, compared with an estimated 65 percent today. Both countries’ foreign reserves dropped dramatically in 2011 and 2012, but Jordan’s almost disappeared in 1988.Over the past two decades, Egypt and Jordan have undertaken serious economic reform efforts. Agreements with the IMF were signed, and many state industries were privatized. Egypt joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. Jordan became a WTO member in 1999 and signed a free trade agreement with the United States in 2000. Both countries signed partnership agreements with the European Union.

As a result, both Egypt and Jordan were able to achieve healthy growth over a sustained period from 2000 until the global financial crisis in 2008. Despite these achievements, average citizens in both countries remained frustrated with a process whose lack of checks and balances left them little control—and with growth they couldn’t see in their everyday lives. What went wrong?

Bread before freedom

Until the uprisings began in 2011, Arab leaders argued that economic reform must precede political reform—the so-called bread before freedom approach. They argued that it was premature and even dangerous to introduce political reform before supplying citizens’ basic needs. Only when those needs had been met could people make responsible political decisions. But that strategy, even when conducted in good faith, did not work as planned.

The approach did preserve macroeconomic stability—which helps the poor, who are the first to suffer in an inflationary, low-growth environment—but failed to yield inclusive growth or address corruption, which multiplied in the absence of parallel political reform.

Economic liberalization—which included not only privatization and freer trade but also more liberal investment laws and stronger integration with the world economy—more often than not failed to achieve either political or economic reform. Because necessary economic measures were not accompanied by development of a political system of checks and balances, abuses by key economic actors went unchecked, and impunity was the rule.

As a result, many economic reform programs benefited only a small elite rather than the general population. The consolidation of benefits in favor of a small group further hamstrung the economic impact of the reform effort. In the absence of strong parliaments able to exercise proper oversight, the privatization of many state industries often took place without complete transparency and led to a perception, often justified, of corruption.

It is difficult to encourage foreign investment if there is no independent judicial system to properly address grievances. And it is hard to curtail corruption, which devours productivity, without an independent press or a strong parliamentary system. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Jordan fell from number 37 (of 178 countries) to number 58 (of 176 countries) between 2003 and 2012. Between 2003 and 2010—just before the revolution—Egypt’s rank fell from 70 to 98.

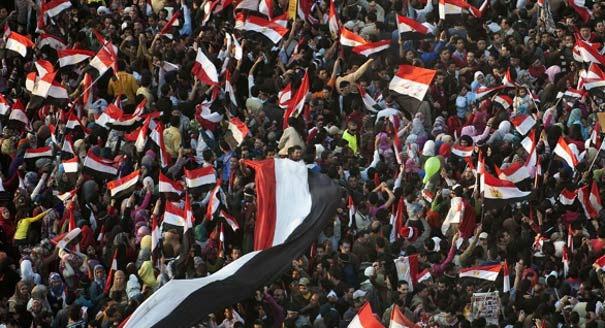

Although protestors’ demands differed widely within and across countries of the Middle East, all sought to combat corruption. In addition to punishment for corrupt individuals, the uprisings called for institutional change to extinguish corruption at its very roots. The protestors believed proper oversight could be achieved by political reform that removed power from a dominant executive and redistributed it among the legislative and judicial branches.

Most of the elite in Egypt and Jordan, and across the Arab world, believed that strong, representative parliaments do not understand economic reform and considered them an obstacle—not a partner—to economic development. Electoral laws in Egypt, Jordan, and elsewhere were designed to produce structurally weak parliaments dependent on and subservient to executive authority and unable to challenge executive branch policies—including the economic policies and practices of the past two decades.

Average citizens were accustomed to relying on government for some of their basic needs. There was no strong legislature to debate a government’s decision to sell state assets, lift subsidies, or maintain liberal trade policies that some considered harmful to local industry. Genuine debate could have demonstrated the transparency and accountability of such decisions and assured average citizens that they stood to benefit.

But clearly the economic reforms of the past—however well constructed or critical—failed because they took place in isolation, without parallel political reforms. Governments often deemed such reforms not only unnecessary but detrimental to economic liberalization, which they feared might stall under a strong parliament.

Market-based economic policy prescriptions that focus on growth but ignore political reform and fail to improve the lot of the less privileged cannot solve the economic problems of the Arab world. The gap between the rich and poor widened in the region over the past two decades, exacerbated by the past few years’ rising food and energy prices and the global financial crisis. This widening income gap is most pronounced in countries of the Middle East and North Africa that import commodities (including food and energy).

The failure in the Middle East of the so-called Washington Consensus of market-based reforms is one of omission. The old policies were not necessarily wrong, but rather insufficient. They ignored the interdependence of political and economic development. If the old policies cannot be applied to today’s new realities, how should countries proceed?

Page from the rule book

Arab countries’ future economic reforms must abide by a new set of rules.

Rule number 1: Economic reform will not work without parallel political reform

Purely economic solutions to economic challenges are not enough.

When Jordan faced a severe economic crisis in 1988 that led to an almost overnight 50 percent devaluation of its currency against the U.S. dollar, the late King Hussein was faced with large government deficits and meager foreign reserves. His solution was largely political: he called for inclusive elections that gave the country its first representative parliament in more than three decades. And it worked.

Jordan not only survived its economic crisis, but the new parliament, even with very strong Islamic opposition, approved an IMF-supported program and several liberalization efforts that led to higher growth rates in the early 1990s. The First Gulf War hit the country hard when all Arab and U.S. aid ended after Jordan opposed the introduction of foreign forces in the region, but there were no protests on the street: people felt their voice had been heard through the parliament. They had a stake in the process.

That lesson was quickly forgotten by countries of the region, including Jordan, whose peace treaty with Israel a few years later contributed to a decision to delay political reform. The past two decades have witnessed a stalling of political reform, with obvious disastrous results. As countries face similar economic crises now—exacerbated by rising energy and food prices, as well as the lingering global financial crisis—they cannot solve their problems simply by taking tough economic measures such as eliminating or redirecting subsidies. People are no longer willing to put up with a dominant executive branch making unilateral decisions that further aggravate their own dire living conditions.

Arab voters now expect economic policy that includes consultation with the people it affects and that is closely monitored by strong, elected, and accountable parliaments.

In Egypt, neither of the two transitional governments that followed the toppling of President Hosni Mubarak was able to sign an agreement with the IMF to get a badly needed loan, precisely because they were unelected and feared public reaction. By contrast, the government formed after the election of Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi is now negotiating a financial arrangement with the IMF, which has historically been suspect in that country.

The IMF itself has learned from past mistakes. IMF financial arrangements with countries of the region since the Arab Awakening emphasize homegrown programs with significant input from the region’s newly elected governments. The arrangements also advocate better-targeted subsidies and subsidy reform and highlight the importance of robust social safety nets, job creation, more equitable income distribution, and improved governance.

All elected governments have a fundamental stake in successfully addressing their country’s economic problems and proving to their electorate that they can deliver greater prosperity. This means that fear of Islam cannot be used as an excuse by the ruling establishment or political elite to block the political progress needed to support economic reforms. There is nothing to fear from Islamists on the economic front. Despite a lack of experience, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) in Egypt, for example, introduced an economic program that should in no way alarm non-Islamists or the international community. The FJP program recognizes the importance of private property and the role of the private sector, a market economy that emphasizes social justice under the framework of Islamic law, and the need for domestic and foreign investment. Economic challenges facing the Middle East may catalyze political reform as they highlight the need for elected governments to make difficult economic decisions.

Rule number 2: Growth policies must be more inclusive

New leaders must be on guard against growth that benefits only a small elite, and economic reforms that speak only to some segments of society. Public demand for immediate improvement—job creation, better wages, and social justice—after the revolutions in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and elsewhere call for a new approach to economic development in the region.

Past economic reforms in the region have led to growth that did not trickle down to the average person. Rather than narrowing the gap between rich and poor, the changes often widened it. Future reforms must have a strong social component that allows the less privileged to improve their lives. Subsidies must be targeted to those who need them most. And governments should make critical investments in better health and education services for the majority of their citizens.

Rule number 3: Economic reform plans must be prepared with society’s input

In the past, reform processes in the Arab world were mostly nominal and written by the regime—often without consultation—and then implemented without question by the government or bureaucracy. More often than not, these regime-led reform processes were insufficient, ad hoc, and poorly communicated. Without buy-in from the general public, not even the best intentions will translate into real change.

These top-down reform projects sometimes resulted in dramatic economic changes and impressive economic growth, including in Tunisia and Egypt. But they did not alter the authoritarian character of the regimes. They also lacked clear strategies for more inclusive growth, so the resulting economic benefits went largely to the business elite surrounding the regime. This did not go unnoticed by the broader public, and hostility and suspicion toward such policies run deep in most countries in the region.

Other projects were the result of social unrest and encompassed limited political reforms. The National Action Charter of Bahrain is one example. Developed in response to public demands for change, the charter was written and implemented as a royal initiative without consultation with diverse social and political actors. The reforms, enacted in 2001, included the creation of two parliamentary houses (one appointed and one elected) and the gradual transformation of the country into a hereditary constitutional monarchy. Despite these programs’ lofty goals, they failed to deliver—the elected house does not exercise true legislative power, and the kingdom is not a true constitutional monarchy. The Bahraini public remains disillusioned by the government and continues to demand change.

Reform projects developed and implemented by the very leadership that needs reforming illustrate the need for programs that adequately represent and empower all the major forces in society. Reform that fails to incorporate the point of view of those affected will neither succeed nor be seen as substantive or credible. When the military leaders in Egypt attempted to set the rules of the political game by diktat after Mubarak’s fall, they were immediately rejected by the public. In the new Middle East, Arab citizens of all political persuasions have been awakened and are focused on changing the game. While proper political institutions are being built, citizens have discovered that their voice can be heard on the street.

Rule Number 4: Economic reform plans must be measurable and point to a final goal

In the past, the reform process has too often been heavy on promises and short on implementation. A clear set of transparent and measurable performance goals will ensure that governments actually undertake reforms and do not fall back on meaningless rhetoric.

At a summit in Tunis in 2004, Arab leaders agreed on a reform document that reiterates their commitment to, among other things, “expanding participation and decision making in the political and public spheres; upholding justice and equality among all citizens; respecting human rights and the freedom of expression; ensuring the independence of the judiciary; pursuing the advancement of women in Arab society; acknowledging the role of civil society; and modernizing the education system.”

Years later, these promises remain largely unfulfilled. That is not surprising, given the absence of evaluation mechanisms to monitor and track progress toward these objectives. The National Agenda effort in Jordan outlined not only final targets, but also milestones, performance indicators, and time frames, but was never implemented, and there has been no comparable effort in the region. Reform rhetoric without results is no longer convincing.

Economic reform plans should also spell out goals—for example, a balanced budget in 10 years or national health insurance for all. Citizens are more ready to accept short-term sacrifices if it’s clear what they are for. Most people in the Middle East feel that governments operate only in crisis mode: they ask their citizens to pay endlessly for administrative excesses, with no payoff in sight. For example, the Jordanian public recently demonstrated against the elimination of fuel subsidies in the face of rising international fuel prices. People must be given a real stake in the process. Even if change takes a long time, policies should be structured to yield some benefits in the early years and to engage citizens at every stage on the way to an explicit national goal.

Rule Number 5: Communication must be a key policy tool

Effective modern communication must never be an afterthought; it must be part and parcel of the planning process, including for Arab economic reform policies.

Communication of reform programs cannot be started after a program is agreed to within the government. Reforms must be prepared in consultation with parliaments and civil society, and their objectives must be clearly communicated by leaders every step of the way. Keeping these programs secret, as has often been the practice in the Middle East, only adds to long-standing skepticism by the public and often leads to outright hostility toward them. As difficult as it might be, communication must be a key policy tool—employed at a very early stage—if there is any hope of achieving

buy-in by the general public.

Got to change

Economic reform processes will work in the Middle East, but not if they follow the models of the past two decades. For economic programs to succeed they must also encompass political elements. The programs must be measurable, broad based, and inclusive—and presented as part of a public plan with the engagement of civil society. Reform initiatives cannot be dictated from the top; they must be agreed to by elected governments. Finally, they must build on an understanding of the links between all aspects of a program. This is the only way to develop and implement a comprehensive approach that addresses the multifaceted political and economic elements simultaneously, with clear and achievable objectives.

The Arab Awakening spurred citizens to expect more from their government. Political change will stall without greater prosperity for more people in the region. At the same time, economic change will not succeed without empowering the key institutions necessary to enable and support the development of more efficient and transparent economic processes. Political and economic elements must work hand in hand to move the region forward.

This article originally appeared in Finance and Development.